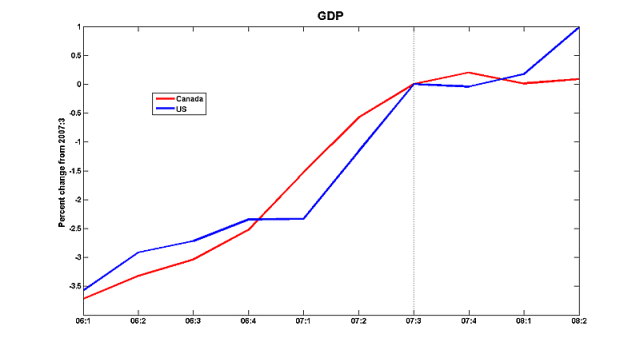

The recent GDP numbers from both sides of the border are somewhat puzzling:

- How can strong US GDP growth be reconciled with all the other bad news about the US economy?

- How can weak Canadian GDP growth be reconciled with all the other really-not-all-that-bad news about the Canadian economy?

Here are a couple of graphs to illustrate the puzzle. First up is Canadian and US real GDP, expressed as per cent deviations from their 2007Q3 values:

Since 2007Q3, US real GDP has increased by 1%, but Canadian real GDP has gone sideways. Even so, there's much more chatter in the US along the lines of 'Are we in a recession?' than up here. A glance at the employment situation might help to explain why. Here are the data for employment, expressed as per cent deviations from their values in December 2007:

Notwithstanding the nasty July numbers, employment in Canada has been growing much faster than in the US over the past few years. If you didn't look at the GDP numbers, you wouldn't be thinking that we were flirting with a recession. As StatsCan's Phil Cross noted, "A recession does not have record-high auto sales and a very tight labour market."

But in the US, the data look very different; Econbrowser's Menzie Chinn feels quite justified in asking 'Why does it feel like a recession?'. He suggests that it has a lot to do with the still-embryonic unwinding of the US current account deficit:

When a country consumes much more than it produces, then at some point,

it has to repay some of the debt incurred. Repaying involves producing

more than consuming. We're not even at that point yet — we're merely moving toward producing more than we're consuming.

That's almost certainly correct, but I think there's more to it. And it comes down – as so many things do these days – to movements in the prices of oil and other commodities and their effects on the terms of trade.

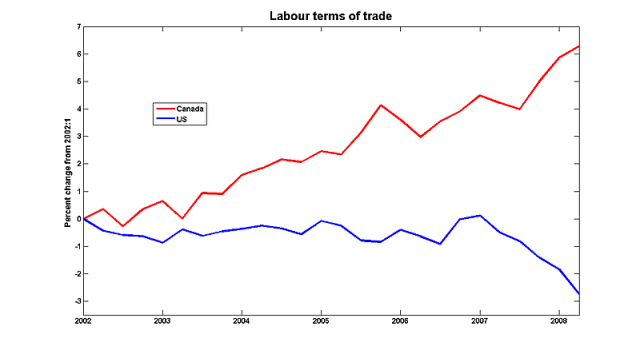

Here is a graph of the effect of the run-up in commodity prices since 2002 on the terms of trade in Canada and in the US:

Since foreign trade is such a large part of the Canadian economy, the improvement in Canada's terms of trade – the fact that we are now able to buy more imports for the same amount of exports – has been the driving force for the increase in real incomes that we've seen over the past few years. Foreign trade is less important for the US, so it's less clear that the deterioration in the US's terms of trade matters all that much.

But it does. A useful metric here is what the development economics literature refers to as the 'labour terms of trade': the ratio of prices of production and consumption goods (see this post for more). When the labour terms of trade are increasing, producer prices are rising faster than those of consumption goods, so the real purchasing power of workers increases, even if productivity remains constant. But when consumer prices are increasing faster than the prices of the goods they are producing, then higher productivity may not be enough to prevent a decline in workers' welfare.

Let's suppose that the GDP deflator is a good measure of output prices, and that the CPI is a useful proxy for the prices of consumption goods. To the extent that consumer prices incorporate the costs of imports, an improvement (deterioration) in the terms of trade will generally increase (reduce) the labour terms of trade. Here is how that's played out in the US and Canada:

In Canada, the continued improvement in the terms of trade has led to a steady improvement in the labour terms of trade. But up until 2007, US consumers had been fairly well insulated form the deterioration in their terms of trade.

But since 2007, the US labour terms of trade have deteriorated sharply: the relative price of producer goods to consumer goods has declined by 2%. Even though the amount produced in the US has increased by 1% since 2007:3, real incomes – measured by the CPI deflator – have fallen by 1%. Add in the reduction in employment, and that would indeed feel like a recession.

The opposite story is happening up here. Although output has remained steady since 2007Q3, the purchasing power of that production has increased by a respectable 2%. All this leads us to the inevitable question of just what is a recession. Is it a reduction in economic activity or of income? Usually it's both, of course, but what do we conclude if we see only one of the symptoms?

To sum up in terms of a not-particularly-clever metaphor, Canada and the US are canoeing in opposite directions on a river with a strong current. The US is heading upstream and paddling hard, but not hard enough to prevent the current from carrying it downstream. Canada is heading downstream, so it can afford to take a break and still get where it wants to go. Which country is in recession? The one that is working hard and going backwards? Or the one that has stopped working but is still coasting forward?