One of the themes being played up in the NDP's convention is its attempt to 're-brand' (up to, but not quite,

including dropping the 'New' from its name), and part of this is

apparently an attempt to develop a credible economic platform. The NDP has historically been pretty consistent in its refusal to take advice from professional economists, so on the off chance that the NDP is serious about this endeavour, I'm starting a series of posts on the economic analysis behind some of its core themes. Below the fold, I'll do a brief survey of what is probably the most important economic issue for the NDP: inequality.

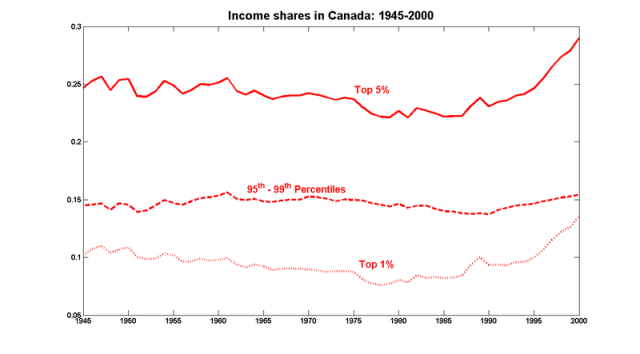

The first point to make is that the problem of growing economic inequality is real, well-documented, and more severe than what you might think. I prepared these graphs for my post on Emmanuel Saez' and Mike Veall's paper on high-end incomes in Canada:

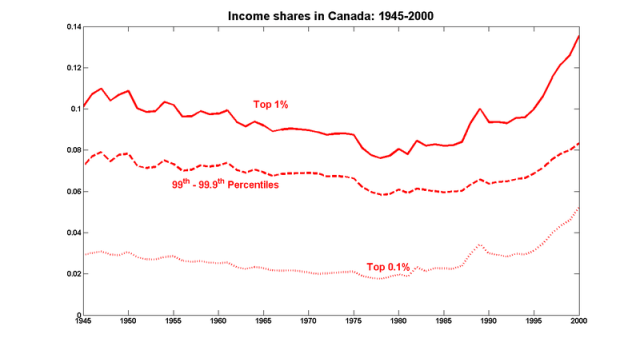

The increase in the income share at the top end of the top end of the distribution is sometimes expressed in terms of the gains in the top quintile (top 20%) or the top decile (top 10%). But it's clear that the real winners since 1985 are those above the 99th percentile. And even within this group, the gains are concentrated at the upper end:

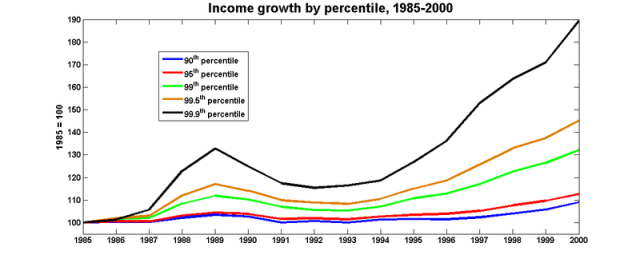

Here is a graph of the income gains by percentile since 1985:

Again, the data are taken from the Saez-Veall article (when oh when will Mike Veall find the time to update the data set?!?).

The fact that the income gains are concentrated at the very top means that the NDP has to be very careful in saying just *who* is in this privileged group. In 2000, the 99th percentile income was $145,774/yr. If we extrapolate the 3.5%/yr growth rate of that percentile over 1995-2000 and correct for inflation, we get something like $240k/yr; the corresponding number for the 99.5th percentile is $380k. These are back-of-the envelope guesstimates, but it gives us an idea of where the line is.

It's important to make this distinction. As a matter of statistics, it's perfectly true that people who are in (say) the top 10% have received the lion's share of gains to national income. But people who are at the 90th or even the 95th percentile could fairly object to such a broad brush, because they – like the people at the median – haven't seen much in the way of increases in income either. So when you talk about 'the rich', it's important to restrict attention to those making (say) $400-500k/yr or more.

Okay, so the problem is real. What can be done about it? The answer to this question greatly depends on the explanation for why income gains have been so tightly concentrated at the top end of the income distribution. Unfortunately, we don't yet have one. There are at least two explanations that sound reasonable, but which are not consistent with the data:

1) Skill-biased technical change. The idea here is that with the advent of the Knowledge EconomyTM, the big winners are those with the skills required to take advantage of new technologies. This would be a convincing argument if the gains were spread out more broadly across those who are highly-skilled, but as we have seen, that's not the case.

2) Stories based on profits. The idea here is that the share of income has shifted towards the owners of capital, and this shows up as an increase in the incomes of the very rich. This may have been a good story in 1946 (when the data start), but it's not a story of what has happened recently. The gains in income are almost entirely due to gains in earned income. In 1946, capital holdings accounted for 53% of the income of those in

the top 0.01%, and 27% was wage income; the other 20% was entrepreneurial

income from self-employment. In 2000, the very rich generated only 25%

of their income from capital, and 74% was in the form of wage income;

entrepreneurs who work for themselves have almost completely

disappeared from the ranks of the very rich. (See also this table.) The increase in inequality has been driven by wages, not by capital income.

The problem remains unsolved. This is why I get very nervous when people like Ed Broadbent call for an 'all-out attack' on inequality. The sentiment is laudable, but there's little reason to think that a bold, comprehensive policy based on a partial understanding of the problem will lead anywhere but disaster.

So what can be done? One thing would be simply to focus attention on the problem: the gains in national income have been concentrated among a very, very small fraction of the population. Not enough people know this.

Given our still-fragmentary understanding of the problem, the only concrete proposal that I can think of that is unlikely to be completely stupid is to add another income tax bracket at the very high end of the income distribution, say those making more than $500,000/year. Make it clear that this measure will be felt by only one person in 200, and that this group has seen their incomes grow at a rate ten times faster than the rest of the population.

There are other things that can be done, of course, and I'll get to them in future posts.

This is part of a series:

- Economic policy advice for the NDP, Part II: Defending big government

- Economic policy advice for the NDP, Part III: The GST

- Economic policy advice for the NDP, part IV: Corporate income taxes

- Economic policy advice for the NDP, Part V: Give money to low-income households

- Economic policy advice for the NDP, Part VI: Climate change

OK – so not CEO’s.

But I still question the long term merits of “winner-take-all” markets. If we think normal people are risk averse, then winner take all markets, not only create inequality, they will reduce the supply of what they want to reward (and reduce the competition). Isn’t that why sports keep wanting to introduce salary caps.

Patrick,

essentially the CEO is saying he is unique (and so can claim quasi-rents) and you aren’t and so get paid the marginal productivity of your class of workers, not your personal actual productivity. We need a few CEO robots. Should be a winning AI application.

I just realised of course, with regard to “winner-take-all” markets, the best example of PRECISELY the problem I mentioned is Microsoft.

westslope

BTW you are bieng disingeniuos in your last comment – i quote you:

“I suppose a Winner takes all approach doesn’t apply to explaining real growth in top executive compensation.”

I would argue this percentile scenario is actually missing a very important aspect that is rearing its ugly head in this economic downturn.

Let’s say we have two people. One person makes 100 Dollars, and the other makes 120 Dollars. The person with 100 Dollars month after month just gets by, and in fact adds on debt. The person with 120 dollars saves 20 dollars a year, getting 10% return.

After year 1 person has debt and has to service this debt, costing them say 50 cents. Person 2 has no debt, but makes 2 dollars.

Let’s fast forward this say 10 years and what you get are the rich getting richer and poor getting poorer.

To prove my point:

Thus the gap between the rich and poor will drop dramatically. Hence the real problem is not to address the gap via restrictions, but to address the gap by giving poorer people a chance to improve their income.