The most recent issue of Canadian Public Policy has this short note:

Minimum Wage Increases as an Anti-Poverty Policy in Ontario: In this article, we consider the possibility of alleviating poverty in Ontario through minimum wage increases. Using survey data from 2004 to profile low wage earners and poor households, we find two important results. First, over 80 percent of low wage earners are not members of poor households and, second, over 75 percent of poor households do not have a member who is a low wage earner. We also present simulation results which suggest that, even without any negative employment effects, planned increases in Ontario's minimum wage will lead to virtually no reduction in the level of poverty.

I've blogged on this before, but it's worth doing so again.

The intersection of … low wage earners and members of poor households … is the target group for poverty alleviation through minimum wage increases. According to our calculations, 17.1 percent of all poor individuals or 23.2 percent of all poor households fall into this category. In other words, an increase in the minimum wage to $9.10 per hour in 2004 would have likely have affected less than one-quarter of all poor households. On the other hand, over 80 per cent of the potential beneficiaries of such an increase in the minimum wage do not belong to a poor household.

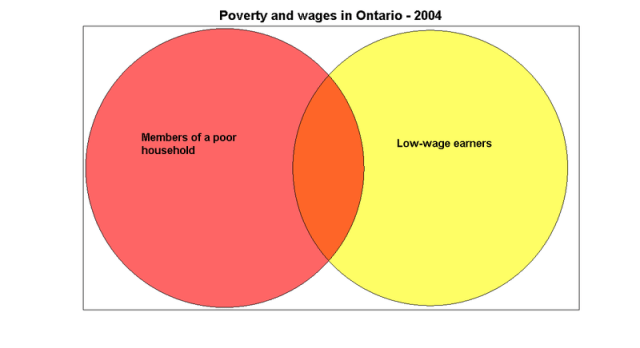

This is the point to take away. According to their data, something like 10.3% of people live in low-income households, and 10% have low wages. The two groups are roughly the same size, but the overlap is small: only 1.8% are in the intersection:

This discrepancy may seem puzzling, until you take into account the fact that almost 90% of low-wage earners are between the ages of 16 and 24 – and most of them do not live in poor households.

Even under the assumption that there are no employment effects, "only 10.66 percent of total wage increases accrue to workers belonging to poor households." Given that 10.3% of households are in poverty, increasing the minimum wage is only slightly more effective as an anti-poverty measure as would be distributing money at random across households.

If employment effects are taken into account, the story gets worse. The gains from higher wages are so small that available estimates for labour demand elasticities suggest that there is a significant risk that increasing the minimum wage will increase poverty.

It would be a good thing if those who were concerned with reducing poverty could stop wasting time on the minimum wage file. As anti-poverty measures go, increasing the minimum wage is pointless at best.

Jim’s theory that minimum wage increases might increase other wages has some merit if we believe that people think of prices relatively. There’s some evidence that this exists in product markets (Predictably Irrational by Dan Ariely has a good discussion about this; people are likely to pay more for a meal at a restaurant if there is an exorbitantly priced dish on the menu than if there isn’t, for example).

Whether people think about their wages in relative terms is an interesting question. My hunch would be that it depends how close you are to the minimum wage. If the minimum wage is $8 and you’re working a $10 job, and the minimum wage gets raised to $9, your $10 wage no longer looks as great. And if the employer’s objective in setting the wage is to make themselves a certain amount more attractive than minimum wage employers, then they might think about raising their wage from $10 to $11. Unions tend to operate on relative premises — “a comparable employer is paying $X” or “our current contract pays $X” so therefore we should get 1.05*$X.

But I can’t see professionals who are paid $20/hour really having their wages affected by a minimum wage increase.

Stephen says he’s looked for evidence that minimum wage increases have increased other wages and couldn’t find anything — I’d be interested if anyone has found any evidence to the contrary too.

What I had found is this and this, both of which find that there are small spill-over effects. Neither study seems to think that they’re important enough to be meaningful for policy purposes.

What I haven’t found is updated evidence that contradicts these studies.

Hmmm. Perhaps it’s a good labour economics study for next semester…

I dunno. I hope you already know how to use the SLID – I’m given to understand that it’s not exactly user-friendly.

I think if you tortured an efficiency wage model enough you could probably get it to predict that an increase in minimum wages would also raise some wages that are already above the minimum. Take the Shapiro-Stiglitz model, replace the unemployment benefit with a minimum wage job (and assume monopsony power in minimum wage labour market so you don’t get unemployment). Then workers who lost a “good job” would work in a minimum wage job. If the minimum wage increased, wages in “good jobs” would need to increase too in order to prevent shirking.

That is likely true in aggregate, however there are localities where they are more significant, low wage tourist areas in particular. Like Newfoundland and Muskoka.

Nick,

Have you ever read Alan Manning’s book “Monopsony In Motion: Imperfect Competition In Labour Markets”? His basic premise is that employers have more bargining power then workers, and that the labour market operates more along the lines of a monopsony model then a competitive model. He gives an example which is what would happen if your employer cut wages by 1 cent an hour. According to the competitive model employers are price takers, and if they cut wages by 1 cent everybody would quit and get a job somewhere else. But in the real world that obviously does not happen and most people wouldn’t care about a 1 cent cut in their wages. But the point he makes is that the labour supply to the firm at the particular wage is not vertical, but due to search frictions for workers the curve is upward sloping.

Chris: I haven’t read it, or heard of it. But from your description, I think I would totally disagree with it.

In a perfectly competitive labour market, all workers would quit if an individual firm cut wages by 1 cent.

In a monopsonistic labour market, some workers would quit if the firm cut wages, with a direct relationship between the percentage wage cut and the percentage of workers who quit (i.e. if a 10% wage cut caused 20% of workers to quit, then a 1% wage cut would cause 2% of workers to quit, roughly). That means there is no threshold wage cut, such that if you cut wages by less than that threshold, no workers would quit. If no workers would quit, a profit-maximising monopsonist would cut wages. So if you assume a small enough wage cut wouldn’t cause any quits, by definition you d not have a monopsonistic labour market.

In a monopolistic wage market, where wages are above the competitive equilibrium, a small wage cut will cause no quits. By definition, wages are above the supply price of labour. If you quit you suffer involuntary unemployment. So if you believe the story about no worker quitting for a small wage cut, that supports the monopoly power theory.

Now, how can there be monopoly power (wages above competitive equilibrium) even when employers seem to have more bargaining power than workers (many little workers negotiating with one large employer, absent unions)? Answer: workers can divorce firms easier than firms can divorce workers. A worker can easily say “I’ve found a better higher wage job, so bye!”. An employer cannot easily say “I’ve found a better lower wage worker, so bye!”.

But I’m thinking more of the Canadian labour market. The US labour market may be a bit different, especially in some lower wage jobs. I wouldn’t rule out monopsony in some low wage jobs, where individual employers find it hard to get workers to take the job and stay, and really might face an upward-sloping labour supply trade-off between wages and number of workers they can get.

I thought I’d just post a link to a review of the book. It isn’t a long read, just if anyone is interested. http://www.econ.ucsb.edu/~pjkuhn/Research%20Papers/Manning.pdf

I strikes me that the real issue is who consumes the majority of min wage products and services we could get to the bottom of this. If poor people consume the majority of these good and services then the increase in the min wage is a neg without the employment effects. If OTOH it is the middle and upper classes which consume the majority of these G&S then…..Look the standard argument assumes that PPs are incapable of increasing their prices in response to increase labour costs. That would be true only if some were touched by the law. But when all are touched by the law it becomes a floor that is non-negotiable. The response of employers in this sector is likely to be two-fold. OTOH, if they are at all in the formal economy they will simply raise their prices. OTOH if they are in the grey economy they will attempt to raise prices and attempt to circumvent the law by for example hiring grey labour. My experience tells me they do both where circumstances warrant. You should really talk to the PPs in your neighbourhood to find out what their response to an increase in the min wage is. It can’t hurt to ask.

Interesting review.

Well, no data, but anecdotally, I think David’s explanation about how minimum wage affects all wages that are close to it are spot on, and is certainly accurate for every retail store owner I’ve ever talked to about this. It’s minimum wage + $1-2 dollars.

And yes, for them labour is pretty much fixed. You can run the store on X employees, and if the labour is half or double what it is now, you STILL run the store on X employees. After all, small retailers don’t pay anything they don’t have to.

Increased labour costs simply comes out of their profits. If it’s not enough to sink them, then you’ve transferred money from profits to employees, if it is, then you’ve thrown all the employees out of work.

I’d like to ask a question here. Given the obvious dislike for minimum wage as an anti-poverty measure, do people here feel that the minimum wage should be abolished and employers allowed to pay the minimum the market will bear?

Personally, I like a highish minimum wage, but that’s because my experience is that employers (and people in general) seem to treat low wage earners vastly worse in a social context. Contradictory thought it seems, my personal experience is that an employer who is paying their workers $3/hr is vastly less concerned about their health and safety than for workers for which he’s paying $10/hr, even for the same job.

It’s psychological game playing, but I think somewhere deep, we equate how much a person earns with their worth as a human being. Anyway, it’s just my observations – but I wonder if it’s the justification that underlies a lot of the support for minimum wage laws by economists who should, by their theory, be against them.

Another arugment I have come across is that high wages will in turn lead to higher productivity. That higher labour costs will cause employers to provide training and/or more capital to their employees to make then more productive to offset the increase in wages. This arugment would also apply to unionization. If we are talking about the minimum wage we might as well as talk about the behaviour of unions on wages and employment.

Yes, I have trouble on US blogs convincing them that the real argument against a mimimum wage is that there are better solutions to the same problem.

But that I think is US specific. It is hard to change in ANY policy in the US (they have a wonderful system of checks and balances that stops anybody for governing), so changing a parameter in an existing policy is a no-brainer for many.

Interestingly, in Germany where I live, changes in social security rules have brought with it demands for a minimum wage – on the grounds of clear cases of abuse – where employers have near the eastern border have sacked all the locals to employ commuters from Poland or the Czech republic. I think there should be a mimimum wage, because of differences in bargaining power when employing very cheap labour, but it should not be too high.

But Chris, if your theory that higher wages create higher productivity is true, employers will have already “upped” their wages because it’s optimal for them to do so. Unless we think employers are stupid.

No, no, no. It’s the change in the wage driven by employee economic power that drives the increased investment in productivity. At the original wage the investment does not produce increased profits. At the new wage it does.

I have to finish the note I was writing on this.

“…a really hard nut to crack is getting teenagers to finish school and to avoid having children before they’re ready.”

I’m thinking back to the posts on a guaranteed annual income. In Dauphin Manitoba in the 70s a GAI was intorduced as a federal-provincial pilot project. I remember reading that after it was introduced one of the two groups that experienced a drop in hours worked was teenagers, who were spending more time in school instead of working. The other group was women with infants.

No, no, no. It’s the change in the wage driven by employee economic power that drives the increased investment in productivity. At the original wage the investment does not produce increased profits. At the new wage it does.

The story we teach is that increased productivity leads to higher wages.

If the reverse were true, Haiti needs only impose a $100/hr minimum wage to become the most productive country in the world.

Your story seems to be one in which employers are deciding a strategy on what to do, given that they must hire someone. But just who is holding a pistol to their heads? Why can’t they simply not hire anyone?

That story is a best incomplete, and probably mostly wrong. I have to work now. I will attack the note tonight.

Caricatures are not helpful in this debate. It’s all about what happens at the margins. If Haiti went to 100% unionization and everybody bargained to the current limit Haiti would start seeing lots of productivity investments.

If they don’t hire anyone they go out of business. That costs.

Actually, I have been wondering if Stephen’s ridiculous Haiti story might have some merit — up to a certain point. There’s marketing and psych literature that shows evidence of product prices having a placebo effect. For example, there was a letter in the Journal of the American Medical Association that found if you increase the price of a drug holding everything else constant, the price increase actually makes the drug more effective.

Most economists I’ve told this theory to kind of raise their eyebrows, so I don’t think anyone has bothered to try answering whether this placebo effect applies to labour markets. But it may be that if we up a wage a certain amount, it may make the labourer more productive through some unconscious psychological process.

But that’s probably a bit of a stretch.

Jim The issue is not having zero workers vs. having X workers, it’s hiring at least one additional worker. The logic is really very simple: If the cost of hiring an additional worker is less than the benefit to the firm of the product of that workers labor, then the firm will not hire. Period. There’s no magic here. No placebo effects or unions or power relationships can change that simple fact.

Tom: Small retailers don’t pay anything they don’t have to because their margins are razor thin.

“Increased labour costs simply comes out of their profits. If it’s not enough to sink them, then you’ve transferred money from profits to employees”

To some extent that might happen. It might also lead to higher prices, which reduces everyone standard of living and then nobody is better of. Assuming competitive markets etc (which is probably not far from reality for the small retailer), making investment less profitable is just going to reduce investment and ultimate increase unemployment.

“But Chris, if your theory that higher wages create higher productivity is true, employers will have already “upped” their wages because it’s optimal for them to do so. Unless we think employers are stupid.”

First off I just stated this was one theory that is usually put out by union supporters etc… on why higher wages do not lead to unemployment. I don’t agree with that per say, as I have not seen any evidence for it as of yet. But from my understanding of the argument is if unit labour costs are rising, and the firm is operating in a competitive market, they may be forced to make investments that make better use of the higher cost of labour in order to bring unit labour costs back down to their previous levels so they can maintain their profit margins.

Hiring additional workers is not the question at hand. It’s: Do higher wages drive productivity investments or do productivity investments drive higher wages?

It’s actually both, with some particular circumstances (higher capital costs, possibly fewer potential workers) to get the second mechanism to work.

I tend to agree that Jim Rootham probably has a point, but as a citizens income (or whatever one wants to call it) supporter, I think it is a better solution. It would have the important effect of increasing the bargaining power of low paid workers (since they don’t HAVE to work). And that for me is the only valid reason for a minimum wage.

Patrick,

that marginal productivity story sounds good, but the real situation, with administrative costs, asynchronous information, training costs, increasing returns ot scale and machine costs is more complicated. The initial choice is always between more overtime and an extra employee. Perhaps supporters of labour should put more effort into insisting on shorter standard hours or higher overtime payments than on minimum wages.

Which goes back to another comment on another thread – there is a tendency in economics to concentrate on a single price ceterus parabus. But maybe economists need to think more about relative to what.

reason – but is it more really THAT much more complicated? I’ve run a business, and things like training costs or administrative costs just figure into the ‘is it worth to hire another employee’ calculation.

“… choice is always between more overtime and an extra employee”

or do nothing because it’s uneconomical to do either of the above.

I don’t dispute that there are market failures and power imbalance and other non-economic issues that are important and contribute to labour getting less than what it should, so let’s address those problems. Minimum wage seems to me to be a hammer in search of a nail.

Patrick,

minimum wages address the most basic market failure – if you don’t have money then the market is irrelevant to you and starvation is a real threat. The most minimal of search costs are excessive.

P.S.

And yes there are better solutions, but until they are in place a minimum wage is better than nothing – so long as it isn’t too high relative to median wages.

I have been wondering about a somewhat different question: the relation between minimum wage and socio-economic stratification. What if the minimum wage had been pegged as a set percentage, not of the mean wage, but of mean income, 40 or 50 years ago? Would it have acted as a brake on the increasing stratification of the intervening years? (Obviously not as much as a peg on top income would have done, but that would probably have been disruptive.) Overall, would it have been a plus or a minus?

Perhaps a higher percentage of the population would now be earning the minimum wage or close to it. OTOH, the minimum wage would be higher than it is now.

What would have been the effect upon unemployment? Perhaps not much. Humans and human systems adjust. A pegged minimum wage would not provide shocks to employment.

If we could afford a certain level of minimum wage in the 1960s, and we are more prosperous now, can’t we afford that same level now?