Ed Broadbent had an op-ed in Tuesday's Globe on a plan to reduce child poverty, and he offers this proposal:

In the next budget, let's impose a six-point increase in income tax on

those earning more than $250,000 a year (whose average taxable income

is $600,000). While leaving them with very high incomes, this would

provide $3.7-billion in additional revenue. All of this should be used

to increase the National Child Benefit Supplement and thus help our

poorest children. With this single act, we would significantly make up

for two decades of neglect and make a major dent in child poverty.

I'm happy to endorse the $3.7b increase to the National Child Benefit Supplement – the costs are small (less than 2% of federal spending), and the gains are huge. But for reasons I'll explain shortly, the tax proposal is not particularly persuasive.

In his article, Broadbent asks

Why is it that Finland, Sweden and Denmark have almost wiped out child poverty, and we have not?

Below the fold, I'll try to provide a partial answer to that question. And I'll explain why the conventional Canadian Left's preoccupation with using the tax system as a way of dealing with inequality and poverty should be rethought.

Here is Broadbent's motivation for the tax part of his proposal:

Almost all income growth has gone to the top 10 per cent, and their share of the national income has substantially increased.

Regular readers will no doubt recall that I've blogged on the concentration of income at the top end of the income distribution here and here. If anything, Broadbent is understating the severity of the problem; the gains are concentrated in the top 1% of the distribution. This matters when it comes to tax policy. As I noted here,

It's important to make this distinction. As a matter of statistics,

it's perfectly true that people who are in (say) the top 10% have

received the lion's share of gains to national income. But people who

are at the 90th or even the 95th percentile could fairly object to such

a broad brush, because they – like the people at the median – haven't

seen much in the way of increases in income either.

It may be reasonable to think that those in the top 1% who have seen strong income growth in the recent past may not react much to an increase in their marginal income tax rates. But this it a much less reasonable assumption to make for those at the 90th and 95th percentiles. Their labour supply elasticities are not zero, and there are limits to how much governments can tax high-income earners before these workers – who are typically the most skilled and the most highly-educated – remove their productive services from the economy.

I like the idea of a surtax on the top 1% or the top 0.5%, but I

view it as a sort of a speed bump to slow a worrying trend; it's not

likely to generate much in the way of revenues. But some serious econometric work would be required before extending it further down the income distribution. (See why we need an effective PBO?)

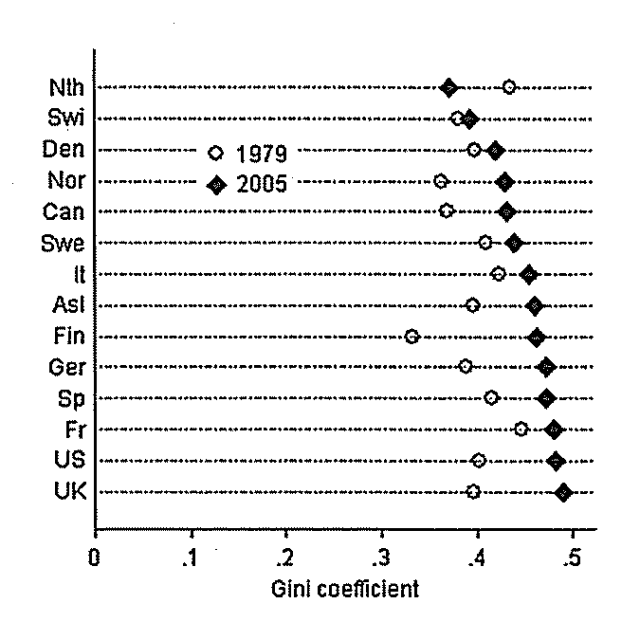

And now we return to Ed Broadbent's question: how do places like Finland, Sweden and Denmark do it? In setting the background for a recent article, Lane Kenworthy sets out some cross-country evidence on market income inequality and how various governments have managed to reduce it. Here is a comparison of the gini indices for market income in 1979 and 2005:

The market income gini coefficent for Canada sits in the middle of the range occupied by Denmark, Sweden and Finland. It is true that the gini coefficients don't do a good job of capturing the concentration of incomes at the top end in Canada, but the answer for lower poverty rates in the Nordic countries doesn't seem to lie in their wage structure. (See also this post.)

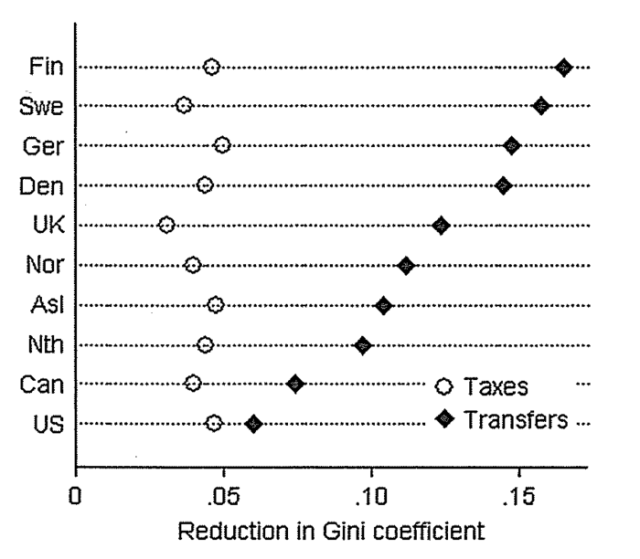

Inequality in market income isn't really a problem per se; what really matters is disposable income after taxes and transfers. Here is how the various governments use these instruments to reduce inequality in market income:

The remarkable thing about this graph is that the redistributive effects of the tax systems of all of these countries are approximately the same, and are pretty small at that. I've made this point before, and it's worth repeating: the countries that have been the most successful in reducing inequality don't have particularly progressive tax structures. The real gains in reducing inequality are achieved by means of well-designed transfers. (See this post for a summary of just how badly the federal government has handled its transfer system over the past 25 years.)

This is not to say that taxes aren't important, of course: those transfers have to be financed. But successful social democracies have learned that the goal of the tax structure is to generate as much revenues as possible with the fewest distortions as possible. As Jean-Baptiste Colbert (finance minister for Louis XIV) famously said, "The art of taxation consists in so plucking the goose as to obtain the largest amount of feathers with the least possible amount of hissing".

This problem is by now largely solved. As this post documents, applying the Nordic model of taxation to Canada would involve lower corporate taxes (the announced cuts pretty much take us there), higher GST/HST rates, and perhaps an income surtax for the very top end.

It's true that these tax instruments probably won't do much in the way of redistributing income, but as we've seen, that's not the point. They are an efficient way of generating tax revenues that can be in turn redistributed in the form of transfers.

Successful social democracies have learned to worry less about taking from rich and to focus on giving to the poor. It's a lesson the conventional Canadian Left has yet to absorb. And until it does, we're not likely to make much progress in solving problems such as child poverty.

I rather think I have; read through the posts in the ‘inequality’ category. Canada’s Conventional Left doesn’t seem to be interested in anything that solid research has actually shown to be effective.

I don’t think Stephen is arguing for less government. If anything, he’s gone out of his way to demonstrate that the federal government has been shrinking for decades. He’s merely arguing for an intelligent tax system, one that can support a robust welfare state without unduly hampering economic activity. He also challenges some of the preconceived notions among those on the left about issues such as consumption taxes and corporate income taxes, and who really pays for them.

Great post. Seems like apparent equity concerns if not outright social envy drives much of contemporary conservative left-wing politics in Canada.

Tried to have some fun with the marketing. How about…. Neo-liberal economic policy analysis at the service of progressive social democracies

A short note on jargon. I like the wiki-pages for learning new definitions or reviewing old definitions. I type w and the term searched in my URL window and up pops the wiki page or a list of wiki pages that are (hopefully) related.

In this case, I thought the definition of quasi-rents was unnecessarily circuitous. Quasi-rents are temporary, simply because the factor of production is in inelastic supply in the short-run but not the long-run.

But overall, wiki is not bad.