David Rosenberg has been saying ([1], [2]) that the Bank shouldn't and/or won't start increasing interest rates until the Fed does, but I don't understand the reasoning behind this conclusion. Usually, the US and Canadian economies follow similar paths and since their monetary authorities have broadly similar goals, this has resulted in broadly similar decisions. But our paths have now diverged, and there's no reason for the Bank of Canada to wait for the Fed to move first.

Firstly, let's set the context by reproducing this graph from this post:

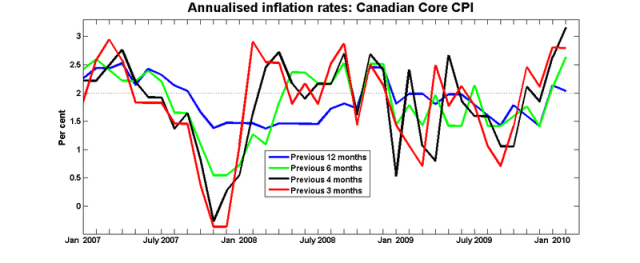

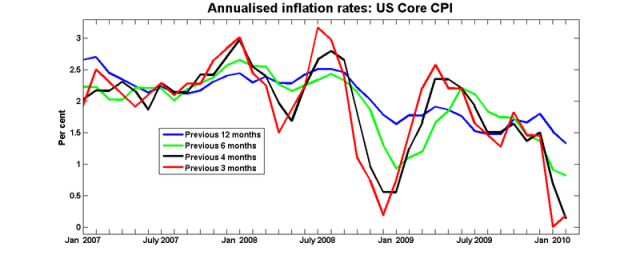

There is still slack in the Canadian economy, but it's dwarfed by that of the US. So it's unsurprising to note that deflationary pressures in the US are stronger that they are in Canada. Here's the latest version of my series of graphs for core CPI inflation over different horizons, updated to include today's CPI release.

And here is the same graph for the Cleveland Fed's measure of core inflation:

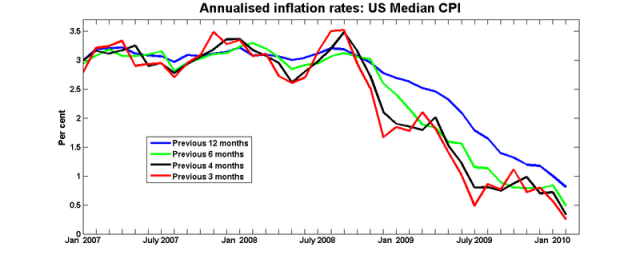

The graph for median CPI is even more striking:

Canadian y/y inflation rates are trending above the 2% target, and the output gap is closing. The proper response to such a situation is to start removing monetary stimulus as the economy improves.

US inflation rates are below the Fed's comfort zone, and there's no sign that the output gap is narrowing fast enough to slow the disinflationary trend. The proper response to such a situation almost certainly does not involve starting to remove monetary stimulus anytime soon.

I don't think the Bank will wait for the Fed to move first, nor do I think it should. I see few benefits from such a strategy, and many dangers. We'd like to avoid the scenario in which inflation drifts so far above target that the Bank is obliged to adopt a tightening stance even before we've fully recovered from the recession.

There are people benefit from loose monetary policy, though. Whether it’s exporters, people who already own their homes, or whomever there will always be people advocating for it. It’s been proven that low inflation is crucial for long term sustainable growth in developed economies; unless the bank is (secretly) abandoning it’s inflation targets it will probably raise rates by summer.

Gordon, how much do you think they’ll raise it? A symbolic .25% or maybe a more practical full percentage?

They have a tough call to make. I wonder what’s driving CPI inflation with unemployment still in the 8% range? Fiscal stimulus? Firms making-up lost ground?

CPI breakdown:

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/cpi-by-province-and-city/article1505516/

Really strange. Why so high in the Maritimes? Still quite a bit below target in the West.

It’s a good analysis Stephen, but I think the CAD/USD exchange Good analysis Stephen, but I wonder if the CAD/USD exchange rate could also play a role. If the Bank of Canada moves first in raising rates, there’s a significant possibility of the Canadian Dollar strengthening well beyond parity with USD. This is something BOC obviously wants to avoid, and it may stay their hand.

On the other hand, if inflation coninues to pick up, the Canadian Dollar will likely strengthen anyways in anticipation of the higher rates to come (as well as because the inflation is a sign of underlying economic strength).

There are two important issues according to Rosenberg:

1. Fast productivity growth allows more monetary stimulus without inflationary overshooting

2. Rosenberg is very concerned with the Canadian housing bubble. Supply response is accelerating, and there is a risk of housing crash somewhere in 2011.

If the Canadian (especially Vancouver) housing bubble crashes in 2011, do Canadian banks hold enough reserves to avoid a financial crisis of the type the US suffered in 2008?

Canadian banks are very well capitalized. Mortgages are recourse, so people will need to declare bankruptcy to walk away from their mortgage. Also, CMHC insures mortgages. The government is on the hook more than anything, but even then, I think it would take a catastrophe greater than a mere 20% correction to put the Canadian banks in danger.

All this said, I think the loan criteria should certainly be tightened significantly. Higher insurance premia on >80% LTV mortgages is probably the best way. I worry that ensuring that people qualify for the 5 year fixed won’t be enough if they opt for variable and rates have to rise significantly.

I expect the BoC to start raising rates with either a 25 or 50 bpp hike in July, finishing the year at 1.25 – 1.5 and finishing 2011 at the 2.75 – 3.25 range. Perhaps lower if the economy cools off again. I think a bubble in China is a serious concern.

I have 1.5 @ end of 2010 and 2.75 @ end of 2011.

The peculiar nature of the Canadian Labour Market (the combination of regionalization especially in the Maritimes and Quebec, plus the UI system which encourages people to stay put and out of a job) means that the Non Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU) is a lot higher, too.

From memory, I think the econometric estimates are that the US NAIRU is 4.5% and the Canadian one 6.5-7.0%. Bank of Canada always has less room to manoeuvre.

Canada’s much higher rate of unionization, especially in the public sector, also means that wages are just not as sensitive to economic conditions. Real wages don’t tend to fall in recession the way they do in the US (real wages adjusted for hours worked ie total income) and as a result, labour gets relatively more expensive.

The normal Canadian response is a currency devaluation. This is how Italy for example historically dealt with these problems of adverse labour cost. With the Euro, Italy (and Greece etc.) cannot do this.

However devaluation means higher CPI.

So the B of Canada simply does not have the Fed’s room to manoeuvre.

The illusion of paper holding a monetary value is finally coming to light, the fiat currency is finally being exposed for what it is 🙂