The federal government won't be bringing its 2011-12 budget down until at least four months from now, but there's already some discussion about just when its fiscal stimulus should be phased out. The government's current line is that the infrastructure program will end on March 31 as planned, with perhaps a certain amount of wiggle room for projects that may not be fully completed by then. There are suggestions that the recovery is still too weak to sustain such a reduction in aggregate demand.

The budget decision doesn't have to be taken right away, so there's no reason to make a definitive pronouncement on the subject just yet. So I'm going to content myself with some context here.

It should first be noted that the process of removing stimulus is already well under way. We all know that the Bank of Canada has already removed its extraordinary measures, and its overnight target has increased by 75 basis points over the past few months. But current policy is still very expansionary:

Inflation expectations are stable at 2% (at least I think so – anyone know if market-based estimates contradict this assertion?), so the real target rate is still negative.

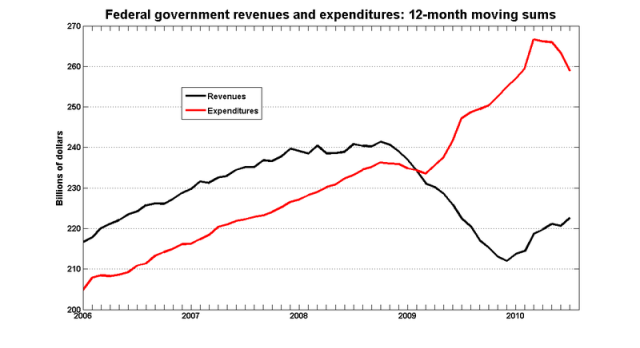

What is less well-known is that the federal government's fiscal stimulus has also started to be scaled back. Regular readers will recall that I've been tracking the Department of Finance's monthly Fiscal Monitor of revenues and expenditures. These data are noisy and have a significant seasonal pattern, so I've been smoothing them by taking 12-month weighted sums. Here is how these series have evolved since the current government came to power:

A couple of preliminary points:

- You can see why we were worrying about a structural deficit before the recession started: a series of tax cuts – notably to the GST – had slowed the growth of tax revenues. Even if the recession hadn't occurred, the trends were pointing to a deficit in 2009.

- For reasons I don't understand, federal spending actually decreased during the first five months of the recession.

Revenues bottomed out in December 2009, and the main sources of revenues – personal income taxes, corporate income taxes and the GST – are all growing.

What strikes me about that graph is that the 12-month moving sum of program spending has fallen by some $7.8b since its peak last March. This can't be explained by lower EI payments: the 12-month sum has fallen by only $500m, only about 6.5% of the total reduction. This could simply be a coincidence: spending that had been planned may have simply not yet been entered into these accounts. But if this is planned, then maybe what we're seeing is a gradual withdrawal of stimulus timed out so that the rate of spending falls to zero when the program is set to expire.

If interest rates had not hit their lower bound, the case for adopting a stimulus package in March 2009 would have been very weak indeed. For one thing, available estimates for the fiscal multiplier looked to be very small. And since its hard to say just what sort of spending should be done and where, it is all too easy for governments to use stimulus funds for partisan purposes.

When the dust settles, I will not be surprised if it turns out that the federal stimulus was ineffective. (This will take some work to determine, by the way. We'll have to develop and estimate a model that can take us through the counterfactual of a liquidity trap without fiscal stimulus. Disregard all analyses that don't do this.) But at the time, interest rates were at – or were soon about to hit – the lower bound, and there was no guarantee that the recession would turn out to be as short-lived or as mild as it turned out to be. The stimulus package was a form of insurance, and it was prudent to hedge against the worst.

In this context, the current case for continued fiscal stimulus looks weak. Employment and output have returned to pre-recession levels, and we are no longer at the ZIRB. There is still a certain amount of slack in the economy, but monetary policy should be able to handle that.

Things could change between now and February. The US outlook is worrisome, so rapid growth seems unlikely: the Bank is right to warn that its interest rate decisions will be based on available data. But it would take a fairly strong negative shock – the kind that would force the Bank of Canada to cut interest rates back down to their lower bound – to make a convincing case for another round of fiscal stimulus.

For a market expectation of inflation you can check RRB prices. The easiest way is to look at the breakeven spread. This shows the difference between RRB’s and nominal bonds, it’s the amount of inflation where you’d ‘breakeven’ by buying one or the other. You can find this easily for the 10 year by searching for cdggbe10:ind. The first hit should be a Bloomberg quote. It’s currently around 2% from a high of 2.5% and a low of 1.8% this year. This doesn’t include a premium for the inflation insurance you get by buying RRB’s. You could say that expectations have been pretty stable and somewhat less than 2%.

Nice summary Stephen, thanks!

brian: good find! The 10 year break-even spread is currently very close to 2%. But strangely, it spiked up to 2.5% around January, and again in April.

Have you seen this IMF paper: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/spn/2009/spn0903.pdf

The authors (including a few Canadians (Freedman, Laxton)) conclude that fiscal multipliers are much larger with accomodative monetary policy (no surprises there).

A properly funded PBO could be scoring the stimulus every quarter.

Lots of interesting information there. But I’m getting more pessimistic, not less. Employment and output may have returned to pre-recession levels but population and potential output growth mean there’s still a gap. Interest rates are not far from the lower bound.

It still looks to me far too much like the great depression. I think output in the depression was back to pre-depression levels a few years in, but that did not mean the depression and the misery of unemployment were over. Also, I think interest rates blipped up in the middle of the depression and in the middle of Japan’s “lost decade”. It’s as if people figure that if they just shut their eyes and start acting as if everything was normal, it will be normal.

And I’m afraid of the mentality that seems to be breaking out all over the world that we must balance the books immediately. Even if Canada doesn’t need more stimulus, the U.S. sure does, and if it doesn’t get it, there will be a big negative shock headed our way. That means I think we do need more stimulus. Think of it, as you said, as insurance.

Out here in the real world, I know of people who have worked all their lives, been laid off, and can’t find work. Some just keep going back for more re-training. No jobs with the training they have, so what else can you do?

I’ve started to call it a Depression. I’ve been job hunting for ages. The lines are a mile long.

I was at one interview where I was told “we like you, we want to hire you, but our customers lost their bank credit and so we can’t because they revoked their orders.”

People won’t call it a Depression unless there are bread lines. Eighty years of social policy have managed to change the face of unemployment, but unemployment is still there. Underemployment is even worse.

We are dashing a generation’s dreams. I don’t know what the Baby Boom expects to retire on if they won’t hire the future workers to produce that future.