Like Peter Dorman, I used to suffer terribly from cognitive dissonance. The theory of perfect competition says that, in equilibrium, firms will be selling exactly the amount of the good they want to sell. But my lying eyes kept telling me that most firms, most of the time, really wanted to sell more than they were able to sell. They always seemed really happy to see an unexpected new customer. It looked like excess supply, nearly everywhere, nearly all the time.

Then I discovered monopolistic competition. And I've felt so much better ever since.

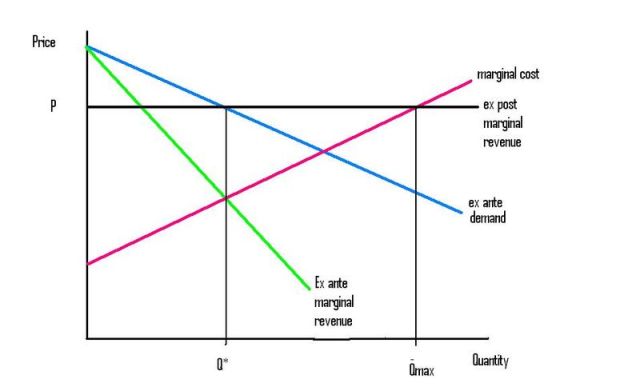

This diagram is for Peter. He is exactly right to feel the way he does. There's something wrong with any economist who doesn't feel that way. This diagram will help me explain what I was trying to explain in comments on his blog.

The firm forms an expectation of where it expects the demand curve to be. That is the ex ante demand curve, with its associated ex ante marginal revenue curve. It then sets a price P, which it expects will lead to sales Q*, where the ex ante marginal revenue curve cuts the marginal cost curve.

So far it's very standard. Now, suppose we hold that price fixed for (say) one month. The firm cannot change that price (because it has already advertised it, say). What happens if demand is bigger than the firm expected, so the actual demand curve (not drawn) is further to the right than the ex ante demand curve? The firm would like to raise its price, but cannot, by assumption. Will it expand production and sales to meet the unexpected increase in demand?

It most certainly will, right up to the point Qmax, where marginal cost equals price, if demand is sufficient to get it there. Why? Because once the price has been set, at P, the ex post marginal revenue curve is horizontal, and equal to that fixed price. Each new sale from increased demand brings in P more revenue. As long as P is above the marginal cost, the firm will increase profits by meeting any increased demand by increasing production and sales.

It would increase profits even more if it could increase price when demand unexpectedly increased. But by assumption it can't. At least, not until next month.

Perfectly competitive firms do not want to sell more at the existing price. Monopolistically competitive firms do want to sell more at the existing price. It will look very much like excess supply.

Nick,

I think you are right, but I am pretty sure this is exactly what Steve Keen has been pointing out for some time. But it is interesting that you came to this conclusion with standard micro-economics. But there may be other factors involved as well. Maybe there is a consistant tendency for suppliers to overestimate their marginal revenue. After all, entrepeneurs are entrepeneurs because they are optimistic folks, and a significant percentage of them go broke, even in good times.

If demand is stochastic, won’t firms hold excess inventories for sort of ‘buffer stock’ reasons? Because of time to build and other considerations, they want to have some spare capacity on hand to take advantage of extra demand. Firms don’t take their demand curves as given but have sales forces etc. exerting effort to push out those demand curves. There’s no point in having a sales force taking orders you are unable to fulfill.

Aren’t there also implications for the relationship between demand and measured productivity? If you always have some slack in the firm, then an increase in demand will look like an increase in productivity too, won’t it?

RSJ: my hunch is that you are right, but I can’t really prove it. The markets that most closely approximate the textbook models of continuous flow auctions of perfectly divisible identical goods with zero transactions costs etc., do have very flexible prices. It’s the markets that are very different that seem to have sticky prices.

reason: I’m not familiar with Steve Keen’s proposed solution to the problem. But the monopolistic comp solution is fairly standard. Some New Keynesian macroeconomists saw it about 20 years back.

Your sample selection bias solution is neat. I could believe it for new firms. But for older firms, it’s hard they could be overoptimistic and make consistent mistakes day after day for years.

Luis Enrique: Yes, they will hold inventories, if they can. I’m trying to do a short post, like this one, only building in inventories.

The marginal revenue product of a sales force is the extra sales per extra salesperson, times the gap between P and MC. So it makes sense to pay people to try to push your demand curve right if P is geater than MC, as it is under monop comp. Yes. Agreed. (Not in my simple model, but can be added).

Yep. The “labour hoarding” hypothesis says that measured productivity should fall in a recession for very similar reasons.

Yes, they will hold inventories, if they can. I’m trying to do a short post, like this one, only building in inventories.

I’d suggest picking a specific industry. The economic rationale for holding inventory differs depending upon the nature of the business. Just in time (JIT) production limits the need for inventory (say automobile assembly). Some high tech consumer electronics (with high margins) have high opportunity costs – and wide dis’n channels – so more inventory in the pipeline. Walmart has driven down costs (and gained market share) through their sophisticated materials management systems, integrating right back to the manufacturer.

One other thing about inventory – it can be used as a short term economic buffer – because it shows up on a firm’s balance sheet – not income statement. The general accounting rule for recording inventory is – the lower of cost or market. And in the “cost” it would include some portion of overheads/semi fixed costs. Of course if the demand continues to fall or remains flat and you are still building inventory, the day of reckoning when you have to cut back production/take more drastic action eventually arrives.

Nick,

thanks for your answer. But with regard to this:

“Your sample selection bias solution is neat. I could believe it for new firms. But for older firms, it’s hard they could be overoptimistic and make consistent mistakes day after day for years.”

I’m not so sure. Older firms are also not static. They have new managers all the time, and new product releases. Maybe internal forces in the firms tend to select for the optimistic ones (for instance people get promoted for being involved in successful projects – some projects are successful – so people promoted for running successful projects tend to think all projects will be successful).

is this the Steve Keen in question?

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2010/11/11/my-lectures-on-behavioural-finance/

The guy doesn’t even understand the most basic expected utility theory. Pretty scary.

Oh God. Adam is totally right. And he really does mean the most basic. Like, utility might not be (and almost certainly isn’t) linear in wealth.

What I can’t understand is how Adam managed to be so restrained in his above comment.

It’s a lack of knowledge of the first year textbook on “why people buy insurance”. Because of diminishing marginal utility. So maximising expected utility is not the same as maximising expected wealth.

reason: maybe. In addition to being really neat, your theory may be a part of the truth. My gut just tells me it can’t be a big part of the truth.

Your theory is like the “Winner’s Curse”, where it is the most overoptimistic person who places the highest value on a used car who buys it at auction. But the winner’s curse does not survive: self-reflection (“hang on, why is everyone else dropping out of the auction? Maybe there’s a winner’s curse?”; and it does not survive learning from repeated experiments.

Nick: “What I can’t understand is how Adam managed to be so restrained in his above comment.”

Well, with effort. Seriously though, Keen shouldn’t be teaching economics. If he was taking first year econ he’d be failing!

One of my abandoned half-assed ideas concerned ‘rational’ over optimism by firms. It’s based on my observations when I used to be a business journalist that too many firms – big old firms – claimed to be planning on growing their market share for that to make sense in aggregate. They can’t all grow market share. I think you can tell a story about it being rational for individual managers all to plan to grow market share. Somebody’s going to lose share, but who wants to tell their boss they’re planning on losing market share that year? You lose your job right there. The rewards are asymmetric, so managers don’t plan like a rational expectations planner. My idea was that during good times when the pie was growing firms accumulate excess (just sub-optimal, not loss making) labour, investment, overheads etc. and get more and more exposed to a negative shock, so when the downturn comes they don’t think ‘no worries, we planned for this’ but ‘oh shit we need to cut costs’. Hard to make work, because really presupposes existence of habitual excess profits without explaining their existence.

[as ever, if somebody realizes this idea isn’t so half-assed and could work, get in touch!]

co-incidentally was discussing Keen last night – my supervisor likes to say that heterodox economists often ask the right questions, even if they don’t always have the right answers and often don’t understand what they purport to refute. You can’t fault Keen for his long-standing focus on debt levels, but Lord some of his ‘take downs’ of mainstream economics are embarrassing.

Shareholders require growth. So senior management is increasingly rewarded for short term performance/stock price appreciation. And this translates throughout the company in terms of KPIs (key performance indicators). On average, I think CEOs last two years, something in that neighbourhood. I’d look at that aspect – the internal reward system. It may lead to overcapacity due to overly optimistic forecasts. Not sure if it would necessarily lead to higher inventory levels. Maybe.

Luis Enrique and JVFM: that reminds me of this old post of mine:

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2009/07/the-cripes-growth-model.html

interesting! It doesn’t have a built in boom and bust business cycle dynamic, which is what I was angling for (I know, yours is a growth model, not a model of business cycles). What I also had in mind (but didn’t say above) is that the over investing, over hiring, might have a sort of Keynesian multiplier demand effect, so some self-fulfilling potential for some period of time … and having firms over expanded during the expansion means they have to over correct in the correction, which creates a larger negative Keynesian demand multiplier in that phase. So I’m thinking of an endogenous cycle story with an amplification effect caused by some moderate collective irrationality. But why would the partially self-fulfilling expansion run out of steam? Perhaps the gap between plans and reality increases every period until people can no longer ignore / deny it, and managers have to correct. Easier to say than to model.