I have a theory.

Employers offer a wage consisting of monetary compensation plus non-monetary benefits. Non-monetary benefits include, for example, free or discounted coffee, flexible work hours, breaks, a safe working environment, and so on. They choose the combination of monetary and non-monetary compensation that allows them to hire the required workforce at the minimum possible cost.

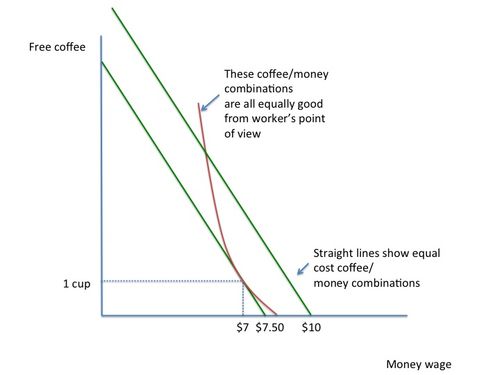

Suppose, for example, one cup of free coffee and a wage of $7 per hour costs the employer the same as a wage of $7.50 an hour. Yet employees prefer free coffee to higher wages. After all, buying coffee would cost more than 50 cents, so the employee is better off with $7 plus free coffee than a $7.50 wage.

So employers will offer free coffee in lieu of higher wages.

Now suppose minimum wage legislation is introduced, bringing the wage up to $10 per hour. Employees are happy – they were willing to work for $7 plus coffee, now they're getting $10 (leaving aside any impact of minimum wages on the number of workers hired.) But the employer will look for a way to cut his or her costs, so the free coffee will go.

Here's a picture:

It's summer, so I'm not going to even try to find data or research to support this theory.

But I tried it out on an employee at my favourite local coffee shop. I asked, "Do you think, if there was no minimum wage, you would get free cake at work?" She replied, "When the minimum wage was $7 per hour, my boss paid minimum wage, and there was no free cake." So I pressed her, "But what if there was no minimum wage at all, do you think your boss might pay, say, $2 per hour and give you free cake?" "Why are you asking me this? There would never be free cake."

My casual observation of minimum wage jobs suggests that employers sometimes do not meet even the fairly relaxed requirements of the Ontario Employment Standards Act, such as "An employee must not work for more than five hours in a row without getting a [unpaid] 30-minute eating period free from work." A 2005 HRSDC assessment of the Canadian Labour Code reported:

The pressures for deregulation have resulted in under-funding of labour standards enforcement and a shift of resources from proactive inspections and enforcement to a program relying on voluntary employer compliance. The results are widespread violations of basic employment rights. Federal evaluations of the program found only 25 percent of employers were following the law; the other 75 percent were in partial or widespread non-compliance with Part III provisions.

But employees don't complain: change is slow, and in small workplaces there is always a risk of reprisals or erosion of trust and workplace collegiality.

What do you think? Do you think that minimum wage legislation causes employers to restrict perks and demand more from their employees? Or do you think employers would restrict perks and demand more anyways?

If we remove minimum wage, people may accept a slightly lower wage for a free movie or coffee, but If they are conscious of the trade off, they will probably feel used and cheated : “I work for you and you won’t give me a free movie or coffee without lowering the expected salary? What am I a cog?” Lowering satifaction with the employer may lower productivity, insite theft, etc…

In other words I expect the trade off would work in cultures where servility to the employer is the norm.

In any way the benefits of having a minimum wage legislation for employees far surpasses any kind of perk an employer would give a “lower bracket” employee…

“7.00$ to 7.50$ and some people get coffee, or everyone gets 10$ but not coffee”… it’s a pretty easy choice…unless you drink wayyyy to much coffee.

Patrick: “At the risk of beating a dead horse: in the economy of 2011 labour and capital have much more in common than either would like to admit.”

I think you should keep on beating that horse, occasionally. You are onto something. A related thought: retired workers are capitalists. Pension plans, and all that. (The more Marx-oriented lefties tend to freak out when I say that. It disrupts their conceptual scheme of workers vs capitalists/managers.)

“Unions are much like any other organization of people who seek to further their common interests. The right to form such organizations is rooted in the right of association, which is fundamental and guaranteed by the Charter. That’s not to say there can’t possibly be good reason to limit people’s right of associate (e.g. we do for lobbyists and politicians), but I think it would be wise to set the bar very high when judging what constitutes good reasons.”

While there is no doubt that the right to join a union is protected by the Charter, its worth noting that most unionized workers don’t “choose”, at least not in an meaningful way, to join a union. If you want to work pretty much anywhere in the public sector, you don’t have the option to be a unionized employee or otherwise. Curiously, the same union activists who (quite fairly) trumpet the freedom of association of their members are somewhat less concerned about the freedom of association of their involuntary members.

I think the bigger problem are the (non-charter protected) labour rights associated with being a union.

“That being said, I think many unions would do well to re-evaluate their notion of self interest. I’ve had some dealings with unions, and while I found them to be very well meaning people who genuinely cared about the plight of workers, they really just couldn’t grasp simple and self-evident facts – like the first requirement for job security is a profitable firm, or that productivity and wages really are connected.”

And, that’s dealing with private sector unions, where employers can credibly threaten to shut down factories. Despite my own anti-union ranting, I’ll freely acknowledge that private sector unions are not impervious to economic reality, and if the CAW can convince GM to pay it unsustainable wages, well, good for the CAW – that’s a problem GM’s shareholders should be taking up with management. At the end of the day, private sector unions don’t bother me that much – hey, I don’t have to buy a GM car.

What I really think gives the union movement a bad reputation are public sector unions, who simply aren’t subject to the hard budget constraints imposed by the requirement that their employer be profitable and where wages are linked to the ability of the government to tax its citizens, not productivity. Let’s face it, government’s can’t credibly threaten to shut down schools, hospitals, public transit, etc (at least not for any length of time). In fairness to public sector unions, this is as much the fault of politicians (who steadfastly refuse to take a hardline with public sector unions – I’m still enraged about David Miller’s capitulation in the garbage strike two years ago) and arbitrators who grant awards which bear no ressemblance to economic reality, as it is union leaders.

Indeed, the constrast between the relative realism of private sector unions and the absurdity of public sector unions has never been made clearer than in the ongoing debate over the HST. In Ontario, the CAW came out quite strongly in favour of the HST, despite the fact that it likely hurt the pocketbooks of its members(on the quite reasonable basis that the HST is likely to be beneficial to the manufacturing sector, and therefore is likely to be beneficial to CAW members in the long run). In contrast, CUPE has been activily encouraging its members to vote against the HST in BC (despite the fact that more efficient revenue raising by the province is likely to be beneficial to its members in the long run). Although that’s a political dispute, rather than a labour dispute, it illustrates a fundamentally different world view between the two unions (i.e., realistic vs. tiny-toon ideological).

Moreover, when you think about it, it’s odd that we’re so willing to tolerate public sector unions providing essential public services. Imagine, for example, if we were to propose giving a private company (or a partnership, or pick your entity) a monopoly on the provision of teaching services in our schools – “If you want to teach here, you have to be a employee-shareholder of Teacher Corp.”. I think it’s fair to say that people would, rightly, go nuts (including, if not especially, the most ardent pro-union activists). On the other hand, if you call the company a “union” and its shareholders “members” that opposition melts away even though, at the end of the day, there isn’t a world of difference between the two (in either case, the union/company is primarily motivated with advancing the wellbeing of its members/shareholders). That’s what really bothers me about public sectors unions, we’ve essentially granted them a monopoly for the provision of services (often, ironically, services, that are publicly provided because we don’t want private sector monopolists providing them – TTC, anybody?).

Most relations of dominance imply common interests and mutual interdependence, the error is to only see the antagonistic relation. One would expect true antagonism to lead to war, not cooperation let alone employment. The workers versus capitalists/managers conception holds in terms of the (often asymmetrical) negotiations over who gets what share of this common interest (i.e. productivity, profit, security) as well as the sharing of burden and loss.

Government employees are in fact in a different relation with their employer…or at least in different conditions… and it should probably be analysed in different terms.

Determinant: “So your original comparison Nick was apples and oranges.”

Let me try again:

1. If employers refuse to trade with me, I can’t earn the money to buy apples and oranges.

2. If supermarkets refuse to trade with me, I can’t buy apples and oranges.

Looks like apples and apples to me.

No.

If employers refuse to trade with you, your entire household budget is blown to smithereens.

If supermarkets refuse to trade with you, you can always go to a restaurant.

The difference is scale and scale matters.

In our economy we generally ration the ability to consume (income) through labour exchange (wages). But we generally supply our labour to one firm and consume from a diverse set of firms. That asymmetry matters.

Agh, summer has really made reading and commenting more difficult.

Not sure if anyone mentioned this as I haven’t had the time to go through all the comments. But what about perverse incentives? If you offer free coffee, then wouldn’t some workers be inclined to consume so much coffee that the employer is actually better off offering higher money wages instead of low wages and free product? It’s probable that employers might restrict workers to, say, one cup of coffee per hour. But workers still could have an incentive to produce more coffee than is demanded in a given period of time, and then consume the rest. It might be difficult to enforce specific quantity limits on free coffee.

Anyway, this was my experience at Wendy’s – basically replace cake with burgers and coffee with soft drinks. Thankfully I found the wonderful sport of squash to shed the pounds.