I finally got around to looking at the OECD Health Data release for 2011 and as is my habit, I spend some time looking at the overview reports and charts as well as playing around with some of the data. The first chart provided by the OECD that I want to draw your attention to is total health expenditure per capita in the OECD countries in U.S. PPP dollars ranked from highest to lowest and and with the public and private shares highlighted on the graph.

Figure 1

Canada is not only the sixth highest spender on health in per capita terms amongst the OECD countries but contrary to our self-image regarding the centrality of our public medicare system, is also one of the countries with one of the higher shares spent privately. The private share of total health spending amongst these OECD countries ranges from a low of 15 percent in Denmark to a high of 52.6 percent in Chile with Canada ranked 12th highest of these countries at 29.4 percent.

It is often remarked that Canada spends alot on health but does not necessarily get the biggest bang for its buck. I began to wonder if health outcomes are affected not only by the amount spent but by the division into public and private spending. Do countries that spend more of their health dollars publically get better health outcomes? I decided to use infant mortality as an outcome measure along with an assortment of health expenditure/resource variables.

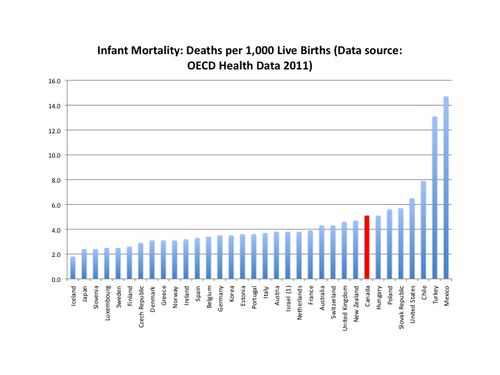

So, I collected from the OECD data information on infant mortality (deaths per 1,000 live births), as well as GDP per capita (in US PPP$), total health expenditure per capita (US PPP$), the share of GDP accounted for by total health spending and of course the share of total health spending originating in private financing. When you rank these OECD countries according to infant mortality, Canada is 8th highest (tied with Hungary at 5.1 deaths per 1,000 live births).

Figure 2

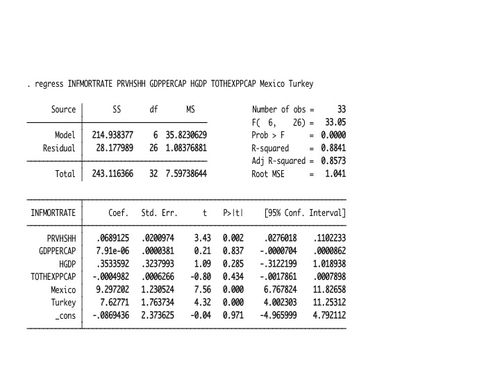

So I ran a quick OLS regression using STATA and regressing infant mortality (INFMORTRATE) on the various health spending and resource measures I had including the private share of health spending (PRIVSH) – I think the other variable names are pretty self explanatory. Because Turkey and Mexico were such outliers amongst the OECD for infant mortality, I put in dummy variables for them relative to all the other OECD countries together. The results are down below:

Figure 3

The results suggest that the infant mortality rate is positively and significantly related to the private share of health spending for these OECD cuntries but is not significantly related to higher per capita GDP (GDPPERCAP), per capita total health spending (TOTHEXPPCAP) or the share of GDP accounted for by health spending (HGDP). I also ran the regression omitting the private share variable to see if any differences might emerge and the health expenditure and the resource/expenditure variables are still statistically insignificant (though higher per capita GDP and higher total per capita health expenditures do have a negative effect on infant mortality).

Figure 4

However, there could be alot of collinearity between the resource variables so one last regression – this time including the private share but only using GDP per capita.

Figure 5

Once again, the private share is positive and significant – per capita GDP has a negative effect on infant mortality rates but again it is not significant. If rather than GDP per capita you include only health spending or only the health spending to GDP share along with the private share, a similar pattern emerges.

Of course, this is a very crude and simple analysis using aggregate expenditure, resource and outcome variables. What exactly is the causal relationship between infant mortality and a larger private health expenditure share underlying these results? Is spending more on health privately drawing resources away from public health spending dealing with maternity? Even if your private share is higher, you should be able to compensate by spending a higher share of the remaining public funds on pre-natal and maternity care if that indeed is your priority. Why should a higher private health expenditure share per se be correlated with higher infant mortality? Does a higher private share of health spending indicate something else about a society's values and priorities that could also lead to an environment with higher infant mortality?

I'm still puzzled as to the exact mechanism whereby a larger public or private health spending share influences a health outcome variable such as infant mortality. I suppose I might also want to try some other outcome measures to see if the result is consistent. At this point, these results suggest to me that once you reach a certain level of economic development and level of health spending (these are after all the OECD countries) how you organize and pay for your health system is probably more important than the actual dollar amount spent on health. In other words, institutions matter. But then, that is what some health economists have been saying all along.

A phrase: Social Determinants of Health.

Looking at health expenditures simply doesn’t cover enough of the story.

Infant mortality in particular is highly dependent on income inequality. If we want better health outcomes we need to get more equality.

Infant mortality is thought to be highly variable in definition from country to country, especially if the US is included. So I am inclined to combine any statistics involving it with a substantial grain of salt.

Regards, Don

I’m not sure how much domestic wages of health care providers, such as nurses, doctors, administrators and technicians contribute to the costs of healthcare, but I imagine they are signficant. The raw per capita expenditures on healthcare should be adjusted for the domestic price or wage levels to avoid creating a misleading picture. Mexico and Turkey have low per capita expenditures on healthcare, in part, because they have lower price/wage levels. Likewise, Canada, Norway and Luxembourg have above average expenditures per capita because prices and wages are much higher.

At this hour and heat I don’t have the time nor the will to run OLS on anything but it seems that the shares ( private vs public ) is a good indicator of inequality and even more on the (un)willingness of the rich to pay for the public health measures that have the highest pay-off ( vaccinations and so forth). Moreover, inequality leads to bad nutrition and housing, both good causes of general bad health, especially for expectant mothers and children.

Same thing with gated communities leading to higher crime elsewhere as no peace ( and so no justice ) is provided for the rest of the populace.

Anyway, the U.S. are a brutal society where vae victis is the national operating principle. And,as much as the Chilean side of my family would protest, so is Chile.

Could the causation be in reverse. If public health care is worse, more money will be spent on private care?

Question: Could it be that private spending on health care isnt intended to reduce infant mortality at all?

Physiotherapy, dentistry, eye surgery, boob jobs,…

This will increase health care spending, reduce the public share of spending and not do anything about infant mortality.

Jacques: Ha! Je viens de terminer de lire l’histoire des patriotes, de Gérard Filteau et j’y ai rencontré l’expression “vae victis” pour la première fois…

Bonne journée

Ask any nurse not scared of losing her job,will tell you there is 3 managers(but they have many names) for every nurse…thanks to Dolton Mc Lair

Livio, do you have data to decompose the infant mortality by income group? (Look how easy it is to ask other people to do hard work.) I’m skeptical of a link because infant mortality (allowing for Don’s correct concern about different measurement practices across OECD) will be concentrated in lower-income groups, and private spending will be further up the SES chain. Hence increased spending on private care (which itself covers a very heterogeneous cluster of goods and services) may not have a clear link to socially-determined outcomes like infant mortality.

If you took the private spending data and separated them out into (1) expenditures on private insurance (such as many people’s workplace benefits), drugs, mobility aids, and a few other items on the one hand, and (2) more luxury-oriented spending like laser eye surgery, psychotherapy, “boob jobs” (as SimonC said) and tattoo removal, it might be more useful to redo the analysis using just the first group. The first group is composed more of the “necessary” health care that will pay for privately if even if they have to decrease spending elsewhere to afford it, whereas the luxury group is just that. I say this because I’m guessing you are looking at spending allocation and cost shifting with some sense of things that are deemed medically necessary.

Another point I would raise is that there are problems with classifying national health care system by private:public ratios. In some situations, the government hires or purchases the goods and services directly, and this is coded as public spending. In other situations, the goods are paid for privately but publicly reimbursed, and there are many situations where this is coded as private spending. If 1 million Canadians get $100 worth of hospital services in 2011, that is $100 million in public spending. If 100,000 public servants consume $1,000 worth of massage, physio, and orthotics in 2011 and are reimbursed by their health plans, that is $100 million in private spending. Having now mentioned the problem, I unhelpfully have no solution.

Finally, the OECD data on Canada are old–there are several categories (particularly on expenditure by funding source) that haven’t been updated since 2004.

Great post, by the way.

Thanks for the comments Shangwen. Those are good points. The infant mortality data from OECD 2011 does not appear to be broken down in that level of detail. However, I suppose one could divide the OECD into low income and high income countries and do the analysis that way. In a sense, that was done by putting in dummy variables for Turkey and Mexico which also have pretty low per capita GDP relative to the other countries and in retrospect probably explains why the GDP variable is not that significant.

Livio, infant mortality rates are very different in Canada’s aboriginal and non-aboriginal populations. The poor health outcomes of the aboriginal population are a key reason why we have a relatively high rate in international terms.

Frances: infant mortality in First Nations communities is almost the same as for non-natives in Québec and Maritimes, especially if you correct for size of communities and distance to health facilities. In Sept-Îles where the Uashat-ManiUtenam Innu reseve is part of the town,health indicators are the same.Same thing for crime statistics. I worked on that with my students when we had a special college program for natives during the 80’s ( now they follow regular programs).

However, in the Prairies,indeed, the results are abyssal. Though far less different from the whites than the American Indians vs white americans results.

SimonC: old enough to have gone to classical college where I learned latin and classical greek. Today’s youth has no idea about what they missed…

I know the intent of the post was not to discuss infant mortality, but here is some additional info to back up what Frances said.

Interestingly, they found that mortality was worse among urban (versus reserve-dwelling) aboriginals. Considering what Jacques Rene wrote, adjusting for geographic factors would then make the results even worse, since they have the same proximity to facilities as non-aboriginals.

When Canada scores well on sub-topics in health, it is typically in areas on which the health care system (i.e., doctors, hospitals, machines, and pills) has little impact anyway, such as life expectancy and self-reported health status.

Finally, a quick overview from the Conference Board, which (because they weren’t addressing it here) doesn’t address the comparatively poor performance of our system in terms of access, timeliness, etc.:

There is a lot of research coming out from the US about positive (and perhaps causal) relationships between health spending and health outcomes, but in my view they target (like the Oregon study) a lot of low-hanging fruit, like highly stressed uninsured poor people. That does not tell us anything about the “right” level of per-cap NHE.

Frances:

Jacques is right. Decomposing Native health can get tricky because of what I call the “Attawapiskat Problem”. Do these these remote communities which are primarily First Nations have poorer health outcomes because they are remote or because they are First Nations? If I lived there would I have similar problems? I think I might and it would have everything to do with location rather than culture.

You can get some inclination by comparing reserve location to health outcome. For instance the Alderville Reserve (Ojibwa) in Northumberland County, Ontario is abuts the village of Roseneath. For all intents and purposes they are the same and everyone attends the same school. What is the difference in health between the village and the reserve? Similarly Curve Lake north of Peterborough can be compared to the neighbouring village of Buckhorn.

There are almost no urban really urban reserve but Kahnawake( Mohawk) near Montréal, Odanak (Abenakis) near Trois-Rivières, Uashat-ManiUtenam (Innu) in Sept-Îles and Wendake (Huron-Wandat) near Québec City are four I know rather well from my Programme amérindien teaching days.

Determinant:

The experiment that you are asking for is currently running there and apart from

a) higher incidence of suicide in boys and

b)higher incidence of diabetes which a common occurence in formerly for a long time long half-starved populations suddenly coming into abundance ( see the well-documented problems of Yemeni Jews coming into Israel in the 50′ and 60’s )

the outcome are not that different.

Frances:

Most urban natives , other than those whose reserve I named, are refugees and live down and out( there is not that many lawyers and economists living professionnal lives in large cities, apart maybe from my two former students who are lawyer and economist…).By definition, their situation is abysmal. The fact that they are natives makes it worst due to language isolation and discrimination ( worse in the Prairies and BC than in Québec-Maritimes)but most of these individual would be hard-luck cases in any circumstances.

Interestingly Curve Lake north of Peterborough, which I know well and some of my family used to work there, had done alright for itself. Lots of kids go on the post-secondary education. In downtown Peterborough across from City Hall there is the law firm of Grant, Wilcox & Whetung (Whetung is the Ojibwa version of Smith, it’s that common). Judge Tim Whetung sits in the Peterborough Provincial Court dealing with our local miscreants, drunks and young offenders. The brother of a Curve Lake friend from school is a Civil Engineer downtown, my first ever interview in high school was with him by pure coincidence.

I had a friend from University who was commissioned to do a “stay in school”: project for First Nations and I was sorry I didn’t get to him in time to direct him to Peterborough. Judge Whetung is impressive to see as he is “the man”.

you have a lot of statistics on infant mortality

In the last year, I have heard right of center economists and others (bloggers) assert that the international comparisons are flawed, because countries measure infant mortality in different ways.

??

” international comparisons are flawed, because countries measure infant mortality in different ways.”

I can’t find an official statement at the OECD site on this for the OECD Health Data 2011 stats, but this has been true in the past in other cross-country comparisons. For example, the official Swiss infant mortality rate specifically excluded the smallest babies (<30cm), which of course are among those most at-risk. Eberstat found evidence that the French and others just omitted counting many day-of-birth deaths.

Dude, you know that putting in dummies for single observations is equivalent to just excluding them from the sample, right?