This morning I've been in email conversations with several economists who do not understand, or disagree with, something in the Bank of Canada's latest Monetary Policy Report (pdf). Specifically, Technical Box 2. These include some very good macroeconomists.

I think I do understand it. And I agree with the Bank of Canada. So I am going to give my interpretation of what the Bank is saying. I think the Bank is right, and it's an important point that we need to understand.

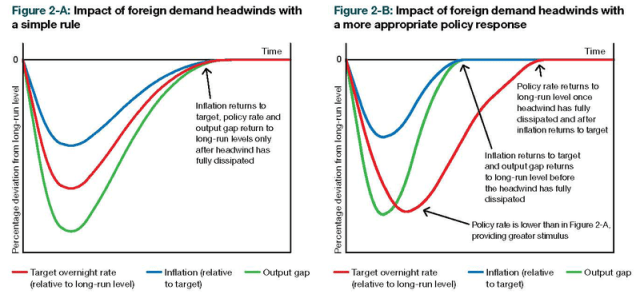

The Bank of Canada is saying that it expects output to return to normal, and inflation to return to target, before the policy rate returns to normal. And that this would not happen if the Bank followed a simple Taylor Rule, but will happen if the Bank gets policy right. A Taylor Rule is not always the best policy. It may not be the same as targeting the inflation forecast.

What may trouble some economists is that if output returns to potential, and inflation returns to target, shouldn't the Bank make the policy rate return to normal too? The Taylor Rule says it should.

Here's the diagram from the Bank's Technical Box 2. (Thanks Stephen!)

Let me give the intuition first.

The Bank of Canada tries to keep inflation at target. Since there are lags in the Bank's response to shocks, and lags in the economy's response to the Bank's response, the Bank won't be able to keep inflation exactly at target. But it does try to adjust policy to keep its expectation of future inflation, post those lags, at target. It is targeting its own forecast of future inflation

And the way the Bank sees itself as doing this is by adjusting the policy rate of interest relative to some underlying natural (the Bank prefers the term "neutral") rate of interest. If the Bank sets the policy rate so that the actual real rate is above/below the natural rate, output will be below/above potential, and inflation will fall/rise relative to expected inflation and target inflation.

Suppose there is a shock to Aggregate Demand that lowers the natural rate of interest. And suppose it is a permanent shock, so that the natural rate is now permanently lower than where it was in the past. If the Bank observes this shock, soon after it happens, and knows that the shock is permanent, the Bank should permanently lower the policy rate of interest in response. There will be a temporary recession, and inflation will fall temporarily below target, because the Bank did nor respond instantly, or because the economy did not respond instantly to the Bank's response. But after a year or two, if the Bank gets it right, those lags have passed, and output returns to potential, and inflation returns to target. But the policy rate of interest stays permanently lower than where it was in the past. There's a new normal for the policy rate. 3% is the new 5%.

And the big problem with a simple rule for monetary policy like the Taylor Rule, is that it can't handle cases like that. The Taylor Rule, at it's simplest, sets the current policy rate as a function of the current output gap and current inflation gap only. So, if it followed a simple Taylor Rule, the Bank in this example would only set a permanently lower policy rate if output were permanently below potential (which can't happen in standard models) or if inflation were permanently below target (which can happen in standard models). The simple Taylor Rule can't handle a new normal.

The above was an extreme example, where the drop in the natural rate was permanent. It was just for illustration, because it's simpler to tell the story in that case.

Suppose, more realistically, that the shock to the natural rate is temporary, but lasts a long time. Specifically, it lasts longer than the lags in the economy's response to the Bank plus the Bank's response to the shock. And suppose the Bank knows this. In that case, the Bank should cut the policy rate in response to the shock, and the economy will eventually respond, so output returns to potential, and inflation returns to target, after a temporary recession. But the policy rate should remain below normal for some time after output returns to potential and inflation returns to target. The policy rate should remain below normal until the natural rate returns to normal.

But if the Bank were following a simple Taylor Rule instead, this would not happen. The policy rate will only be below normal (the old normal) if output is below potential and/or inflation is below target. And unless the policy rate is below normal (the old normal) output will be below potential and/or inflation will be below target. So, with a simple Taylor Rule, output will be below potential and/or inflation will be below target for as long as the natural rate stays below normal (the old normal).

And that is precisely what the Bank's two pictures are showing.

And this is important because I think the Bank's assumptions are reasonable. The global economy has been hit with a serious shock to demand, that has lowered the natural rate, and this shock to the natural rate will probably last for some time.

Here's a crude model:

Let P(t) be inflation (or the deviation of inflation from target), Y(t) the output gap, R(t) the policy rate of interest, and N(t) the natural rate of interest. (Both R and N are in real terms, to keep the equations simple. I have also ignored a lot of constant terms and set most parameters to 1 to keep the equations simple.)

IS Curve: Y(t) = N(t) – R(t-1)

This is fairly standard, except I have introduced a 1-period lag in the economy's response to the Bank's policy rate, so the Bank can't perfectly stabilise the economy.

Phillips Curve: P(t) = Y(t) + 0.5 E(t-1)P(t) + 0.5 E(t-2)P(t)

This is fairly standard, if you assume something like overlapping 2-period nominal wage contracts. E(t-1)P(t) and E(t-2)P(t) mean the expectations at time t-1 and t-2 of the inflation rate at time t.

Shocks to natural rate: N(t) = S(t) + S(t-1)

S(t) is a serially uncorrelated shock, so the natural rate follows an MA(1) Moving Average process.

[Update: Curses! I think this should have been an MA(2) process. Make it N(t) = S(t) + S(t-1) + S(t-2) instead.]

Run this model through two alternative policy rules:

2a. R(t) = Y(t) + P(t)

This is a Taylor-like Rule. Remember R(t) is the *real* policy rate, so this satisfies the Taylor/Howitt principle that the nominal policy rate responds more than on-for-one with inflation.

2b. R(t) = EtN(t+1) + bEtP(t+1)

This is the optimal monetary policy rule in this model for keeping next period's inflation on target in this model. The Bank sets the (real) policy rate equal to its expectation of next period's natural rate. (The second term isn't really needed; it's just to rule out indeterminacy of the inflation rate and satisfy the Taylor/Howitt principle).

Now suppose that S(t) < 0. All other S shocks are zero. Given the MA(1) structure to the natural rate, this means the natural rate falls at time t and stays below normal for 2 periods in total, then returns to normal.

With policy rule 2a, the Taylor Rule, you get something roughly like the Bank's figure 2a. The economy has a 2-period recession, with inflation below target for 2 periods, and the (real) policy rate below normal for 2 periods.

With policy rule 2b, you get something roughly like the Bank's figure 2b. The economy has a 1-period recession, and inflation below target for 1 period, and the (real) policy rate below normal for 2 periods.

I think I've got that right. Not 100% sure. Never could do math. Somebody else can solve the model and check for me. It's not my comparative advantage.

K: doesn’t that lead to the circularity problem?

K:

Forget the Bank of Canada for a minute. Let’s think about EMH. I think EMH is neither true nor false. Traders make forecasts, and prices depend on traders’ forecasts. Then next period other traders look back over the history of prices, and try to spot systematic errors in past forecasts, and if they find some they adjust their forecasting models, and the pattern of prices changes in response to those changing forecast models. And repeat, forever, while the underlying structure of the world changes, both for exogenous reasons, and because traders’ forecast models are changing. EMH is more of a process than a statement about how the world is.

The Bank of Canada is similar. It targets its own forecast of 2-year ahead inflation. And the pattern of inflation we see depends on the Bank’s decision rule, which depends on its own forecasting model. My idea is that it starts out with some decision rule, then next period look back over the history of inflation, to see if 2 year ahead inflation could have been predicted, to try to spot systematic errors in its past decision rule, then adjust its decision rule accordingly, then repeat.

Both can be seen as cases of adaptive learning. The second is also adaptive control.

Yes, if the TIPS spread is an efficient predictor of future inflation, and if the market learns faster than the Bank, you might argue that the Bank should just leave the learning to the market, and target the market forecast. Circularity problem aside, I’m agnostic on that question. I was just taking as given that the Bank targets its own forecast, not the market forecast.

The fundamental questions are:

1. Has the neutral rate fallen?

2. If so, what factors would explain its fall?

If everyone believes that neutral is still around 4%, then simple policy rules would dictate that the BoC should have continued with the overnight rate increases that began last year. However, if neutral is now at 2% due to foreign headwinds, then the BoC is justified in keeping the overnight rate lower for a longer period of time.

The challenge for economists is to quantify the impact of these headwinds on the neutral rate; the challenge for the Bank’s communication department is to explain all this to the public without fully defining what the neutral rate is, where it was in the past, where it is today, and where it is likely to be in the future.

Nick, you’re breaking my heart! You have a PhD, I have faith in your ability to master the math!

Anyway, it all begins with a little simplification. All those s equations are Laplace Transformations. Differentiation is given a differential operator s and integration is defined as 1/s. Then you though in the initial conditions and you get an equation.

PID controllers imply s^2 as the highest dimension in the equation.

Maybe next summer you could hire an Engineering grad student to do the math for Nick’s Adaptive Inflation Controller (Patent Pending). Come on, there has to be at least a few papers in that.

Determinant: thanks for your faith in me! But I have to confess you lost me at “Laplace Transformations”. I don’t know what they are.

Greg:

1. If you believe the IS curve has shifted left, and the LRAS curve has not shifted (or shifted right), then I would say that by definition the natural rate has fallen.

2. That’s like asking “what caused the recession?”. At least, within the New Keynesian/Neo-Wicksellian paradigm followed by the Bank.

I agree with the rest of your comment.

Determinant’s head hits keyboard

Nick, Laplace Transforms allow you to linearize differential equations and solve them using ordinary algebra and a transform table!

How could you even look at a differential equation and not think of using them? Dear me, what happened to your math education?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laplace_transform

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laplace_transform_applied_to_differential_equations

The Laplace Transform turns integration and differentiation into division and multiplication.

Determinant goes over to couch to lie down and recover.

“Jacques pats Determinant’s head with a cold towel as he remember how in 1975 first-term Calculus for economists 1 he learned Laplace Tranforms but then Laval was a math hotbed. Jacques ponders how he was a soldier once and young, or at least a physicist fresh from Mathematical Physics 2 and thought that economists had it easy as they didn’t have to go through Kreyszig’s Advanced Engineering Mathematics …”

Jacques also thinks that he should stop thinking about Laplace transforms and should finish booking his trip to the U.S. Air Force Museum as even Ken Kesey likes to look at a few hundreds pieces of good engineering.

Okay, okay but you do know the z-transform right?

Well… usually that handled with the “I”, the integrator. So given the premise that some coefficients in the taylor rule will give a steady-state error of zero, you’ll find it, but so would simply integrating the output and inflation gap, so that persistent errors produced stronger policy responses.

The gains are really selected on rather different grounds:

– Stronger gains tend to mean a faster settling time. i.e., how quickly following a disturbance does the system return to the targets

– Stronger gains eventually lead to overshoot

– Time lags (such as in computing output even if you believe policy is instantaneous) mean some gains (too weak will produce instability and some gains (too strong) will produce instability.

Andy Harless wrote:

Control theory intuition neatly explains why the gains in the taylor equation cannot be too large.

It also suggests that performance would be improved with an integral term. That’s again the “I” and its what Andy’s getting at without knowing the language when he wrote:

Interesting, this could be more effective in the economic context because of expectations.

Jacques: thanks for those memories. They give me solace. I took math A-level at school in England. And got a grade of D. But then it was the early 1970’s, and a lot of other distractions were happening for a teenage boy. Then a quick one-term math course for incoming MA Economics students at UWO, where I first learned what a matrix was, and how to calculate a determinant (though I have forgotten since). I’ve been faking it since then.

Jon: “Okay, okay but you do know the z-transform right?”

Nope. Never heard of it. Or maybe I have, but have forgotten. And I can’t understand those Wiki pages Determinant helpfully linked for me.

“Well… usually that handled with the “I”, the integrator. So given the premise that some coefficients in the taylor rule will give a steady-state error of zero, you’ll find it, but so would simply integrating the output and inflation gap, so that persistent errors produced stronger policy responses.”

That’s different. Suppose the Taylor Rule says R(t) = 5% + 1.5(deviation of inflation from target) + 0.5(deviation of output from potential). And suppose the bank is targeting its forecast of 2-year ahead inflation, trying to keep it at a constant 2%.

If you find that inflation was on average below the 2% target, when that Taylor Rule was being followed, then you know the constant term, 5%, is too high. So you slowly revise that 5% down.

Suppose instead you noticed a positive historical correlation between the output gap and 2-year ahead inflation. That is telling you that the 0.5 coefficient is too small, and should be adjusted up to 0.6, or something. (And if it’s a negative correlation, that is telling you that the 0.5 coefficient is too large, and should be adjusted down to 0.4).

And if you noticed a positive correlation between current inflation and 2 year ahead inflation, that is telling you that the 1.5 coefficient is too small, and should be adjusted up.

And if you noticed a positive/negative historical correlation between X and 2 year ahead inflation, that means you should add X to the Taylor Rule, with a small positive/negative coefficient. (Assuming the Bank observes X).

If anyone is really into this, here’s my old stuff:

economics.ca/2003/papers/0266.pdf

My point was slightly different which comes down to: there are simpler

Methods in common use.

I agree that what you want is different. What I want to know is why you think it’s better ( which it may well be )

Jon: OK. Let me first try to understand better your “simpler methods in common use”.

In order to handle the case where the constant term is too big (the 5% should be 4%, so we get inflation on average below target), I can think of two different versions of that “simpler method”:

1. Change the Taylor Rule to: R(t) = 5% + b[R(t-1)-5%] + 1.5(inflation gap) + 0.5(output gap)

2. Change the Taylor Rule to R(t) = 1.5(inflation gap) + 0.5(output gap) + b(integral of inflation gap over time) (b less than or maybe equal to one)

1 is what the central bank seems to do in practice. It has been rationalised as “interest rate smoothing”, but I see it more as a way for the Bank to adapt towards a natural rate that is moving over time in some sort of persistent way.

2 seems to me to end up in price level targeting, which might be a good policy, but if what you are trying to do is inflation targeting, this doesn’t seem the right solution.

Plus, neither of those two methods seem to deal with the case (the one I concentrate on) where the coefficients 1.5 or 0.5 are wrong, so the Bank is over-reacting or under-reacting to fluctuations in inflation or output.

The scale factor of the integral term can be above one just as the constants by the proportional terms need not sum to 2 or 1 or any other value you may pick.

Second whether this behaves as price level targeting will depend on the magnitude of the proportional and integral terms. Indeed, I’ll claim that price level targeting is equivalent to omitting the proportional terms.

What this means is, in part, that level vs rate targeting is a false dichotomy.

The integral term will always drive the steady state error to zero. Now I suspect that’s not what you mean by over an under reacting.

Perhaps what you have in mind are the two ideas I mentioned before namely how quickly the policy returns us to equilibrium after a disturbance and whether it does so with overshoots.

So which of those ideas do you have in mind?

Jon: Let me try to formalise my ideas a bit more.

Let P(t) be inflation, R(t) the policy rate chosen by the Bank, and I(t) the Bank’s information set at time t. Assume perfect memory by the Bank, so I(t) includes I(t-1) etc. I(t) also includes R(t). (I.e. the Bank knows what policy rate it is setting, and has set in the past.)

The Bank has a reaction function F(.) that sets R(t) as a function I(t). R(t) = F(I(t)).

The Bank is targeting 24 month ahead inflation. It wants inflation to return to the 2% target 24 months ahead, and stay there. (It fears there will be bad consequences if it tries to get inflation back to target more quickly than 24 months ahead). But there will be shocks that it can’t anticipate, so it knows that future inflation will fluctuate. Instead, the job is to choose some function F(.) such that:

E(P(t+24) conditional on I(t) and F(.)) = 2%

(And E(P(t+25) conditional on I(t) and F(.)) = 2% etc.)

Suppose that the Bank has been using some reaction function F(.) for the last 20 years. Looking back on the last 20 years of data, we estimate a linear regression of P(t)-2% on I(t-24). We exclude R(t-24) from the RHS that regression, because leaving R(t) in would cause perfect multicolinearity between R(t) and the other elements of I(t). If the Bank has chosen F(.) correctly, the estimate from that regression should be statistical garbage. All the parameters — the constant and all the slope terms — should be insignificantly different from zero.

If that linear regression is not garbage — if some of the parameters are non-zero — we know the Bank has made systematic mistakes over the past 20 years.

If the constant is non-zero, we know the constant term in F(.) is wrong. If the slope on some variable X(t) within I(t) is non-zero, we know the coefficient on X(t) in F(.) is wrong. The Bank either over-reacted (the coefficient on X(t) was too large) or underreacted (the coefficient on X(t) was too small) to changes in X.

We could also estimate a regression of P(t)-2% on R(t-24). That regression should also be garbage, if the Bank has chosen F(.) correctly. If the estimated slope coefficient in that equation is non-zero, that tells us whether the Bank overreacted or underreacted to fluctuations in everything else in I(t).

Yes… I understand your view here.

But, suppose: its not generally possible for a causal system in the presence of lagged information to exhibit the property you mention, no matter how much you tune those constants.

I assert that the reason this must be so is that following a disturbance, you must react exactly strong enough to reject the disturbance in zero time and then go slack. A time lag represents a filter–events higher frequency then the lag are not visible. So you cannot have a step-response as would be necessary for there to be no systematic mistakes–since the fourier transform of such a step-response has frequency components higher than the lag.

So does your scheme have a unique solution at least? (or is there a family of solutions which achieves some lowest possible correlation–I think this more likely)