The debate about income inequality seems to be happening at two levels, which I'm going to label "first-order" and "top-end" inequality.

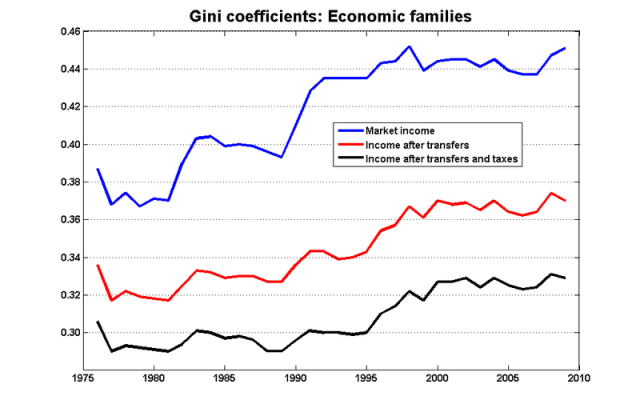

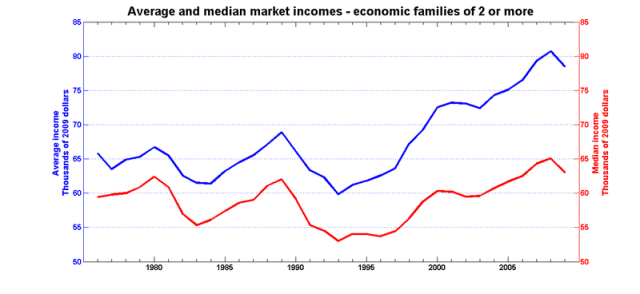

- First-order inequality is visible in standard measures such the gini coefficient, and shows up as an increase in the gap between average and median incomes.

- Top-end inequality refers to the share of income that goes to those whose income puts them above the 99th percentile and beyond.

(If I'm giving new names to phenomena that have already been defined, please let me know in the comments, and I'll make the necessary changes.)

I think it's important to make this distinction: top-end inequality generally doesn't show up in first-order measures, and vice-versa. And each type of inequality has its own challenges for policy.

Here is an exerpt from a very nice column by Pete McMartin, in which he quotes Kevin Milligan:

In the aftermath of the HST referendum, Kevin Milligan, a University of B.C. associate professor of economics, came across a poll that caused him pause. Milligan, who specializes in tax policy, had campaigned hard for the harmonized sales tax, believing it to be good for the economy.

The majority of respondents in that poll agreed with Milligan. They, too, felt that, overall, the HST would benefit the economy.

But oddly — and here is where the respondents’ opinions diverged from Milligan’s — while they recognized the HST would benefit the economy, they also felt that, on a personal level, none of the HST’s benefits would accrue to them.

A message resided in that distinction, Milligan felt, one that perhaps spoke to a greater malaise.

“With all the growth in the economy the HST promised,” Milligan said, “these people couldn’t bring themselves to vote for it because they didn’t see that growth benefiting them.”

(Here is the poll Kevin was talking about.)

This is a first-order problem. Economists will often concentrate their attention on the question of whether or not a policy will increase total – and hence average incomes. Behind this choice is an implicit assumption that most people should see some benefit, or at least that the number of those who benefit outnumber those who lose out. But if this isn't the case, then we end up with what we saw in BC: people rejecting a policy that they believe will increase average incomes.

First-order inequality is – in my view – a far more important problem than top-end inequality. It also turns out that in Canada, it's one that seems to have stabilised, albeit at levels that we may not find acceptable. Here is a graph from an earlier post:

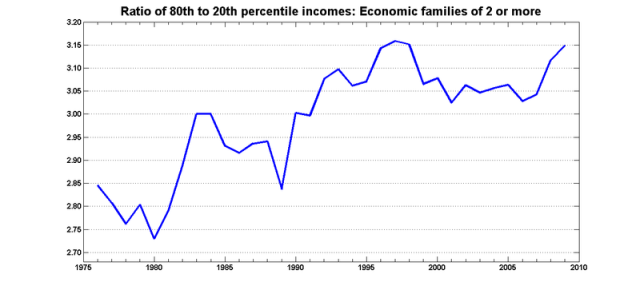

Here is a graph of the ratio of the 80th and 20th income percentiles:

The divergence between mean and median incomes is a first-order concern:

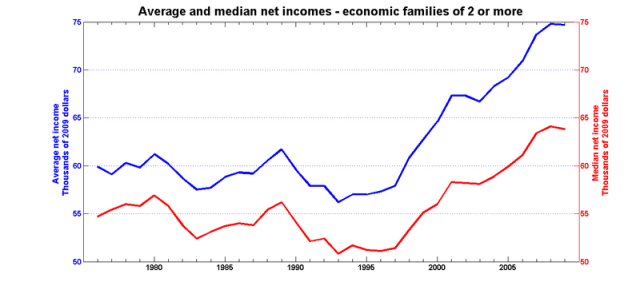

Here is the same graph for incomes after transfers and taxes:

The story before the mid-1990s is pretty grim: stagnant incomes and increasing inequality. But first-order measures of inequality have levelled off since then, and median incomes – in particular, median incomes after transfers and taxes – have grown appreciably. To a very great extent, the belief that most people have not benefited from economic growth is not consistent with data from the last fifteen years. Moreover, the recipe for reducing first-order inequality is fairly straightforward: strengthen the system of transfers.

Top-end inequality is very different. Firstly, it shows no sign of slowing. And since we're not entirely sure why it's happening, it's not immediately obvious that measures such as a high-income surtax will have any more than a symbolic effect. For that matter, it's not clear how improving transfers would affect top-end inequality.

More fundamentally, the questions that are raised by top-end inequality quite different from those raised by first-order inequality. Top-end inequality raises the spectre of a tiny economic super-elite using its income and wealth to establish its dominance in other areas of society.

A solution for one sort of inequality is unlikely to do much for the other. We've already seen a levelling off of first-order inequality, and that didn't stop the worsening of top-order inequality. Nor does it seem likely that a solution to top-end inequality would do much for the first-order problem; the numbers involved are simply too small.

I think this distinction is important:

- Arguments to the effect that inequality is stable because the Gini index has levelled off are addressing first-order inequality, not top-end inequality.

- An excessive focus on top-end inequality – at the expense of first-order inequality – means that too much attention is paid to taking from the rich, and not enough to the other half of Robin Hood's agenda.

Bob: causation runs in the other direction as well. Unemployed or underemployed men make less attractive marriage prospects. Economic changes (technology, trade, inflation) which result in less income for unskilled male workers will reduce marriage rates and increase divorce rates.

(By the way, if you haven’t read Tony Judt’s “Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945”, I’d highly recommend it. Judt does an excellent job of describing both economic and social changes, not just political history.)

Mandos: “Why do people think that it’s a good thing to let democracy be tossed aside?”

Anthony King calls this the “division of labor” view of democracy. The role of the voters is to choose a government; the role of the government is to govern. At election time, the voters judge the government on its overall record. Between elections, voters don’t get involved in day-to-day decision-making. (This is very different from the “agency” view of democracy which prevails in the US.)

http://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/issues/97jan/scared/scared.htm

I’ll tell you what the “division of labour” view of democracy is: not. “You don’t worry your pretty little heads about it.”

“Bob: causation runs in the other direction as well. Unemployed or underemployed men make less attractive marriage prospects. Economic changes (technology, trade, inflation) which result in less income for unskilled male workers will reduce marriage rates and increase divorce rates.”

Fair enough, causation could run the other way (although I don’t recall, was their a decline in marriage rates during the Great Depression?). Still, it’s interesting that the divorce laws of Canada, the UK, and Sweden (to say nothing of other developed countries) were all substantially liberalized in the late 60’s early ’70s. I don’t think one can credibly claim that economic factors drove the entirely of the breakdown of marriage.

Bob Smith: “although I don’t recall, was their a decline in marriage rates during the Great Depression?”

Yes, a very pronounced one.

” Globalization and technology are plausible candidates, but I’d think that changing societal attitudes towards marriage would be, superficially at least, and equally plausible alternative.”

Changing attitudes towards marriage went hand in hand with changes in technology. The birth control pill. Washing machines, dishwashers, freezers, fridges, cars, etc.

“Changing attitudes towards marriage went hand in hand with changes in technology. The birth control pill. Washing machines, dishwashers, freezers, fridges, cars, etc.”

I’ll concede that point (although, strictly speaking, cars, frides and washing machines all pre-date changing attitudes towards marriage, but I can accept that there would be a time lag), but the usual story isn’t that income inequality is rising because of the pill, washing machines and dishwashers. The usual technology story is that technology reduced the demand for unskilled labour while increasing the demand for skilled labour. Plausible enough, but maybe technology drives family inequality through its interaction with social values.

In any event, that misses the point. To the extent that family income inequality is increasing as a result of changing family structure, that really isn’t something that we can do much about (short of holding a gun to peoples heads and telling them they have to get married), nor it is something that we should care about (at least, not because of inequality, I think there is an argument that governments should want to promote two adult families, but that’s a different discussion). Fitzgerald’s point was that some of the apparent stagnation in family income wasn’t a function of family incomes actually stagnating, it was a statistical ghost that resulted from comparing apples and bananas. I’m just wondering if that logic extends to inequality.

Bob: “To the extent that family income inequality is increasing as a result of changing family structure, that really isn’t something that we can do much about–”

Wait, why does the cause matter? I assume that the government shouldn’t be attempting to change family structure directly; but if there’s more divorces and single-parent families, then poverty and inequality will increase, because it’s considerably more expensive to maintain two separate households than a single household; in other words, it’s not just a statistical artifact. This would suggest increasing redistribution to compensate.

One of Kevin Milligan’s papers notes that child benefits make a measurable difference to child well-being (not surprisingly, given the importance of income instability as a factor in overall household stress).

Bob: “To the extent that family income inequality is increasing as a result of changing family structure, that really isn’t something that we can do much about–”

There are substantial “marriage” (strictly speaking, cohabitation) penalties built into our tax-transfer system – if a single parent with a couple of kids and a minimum wage job marries someone else with a minimum wage job, they will see quite substantial loss of government benefits.

Russil Wvong: “One of Kevin Milligan’s papers notes that child benefits make a measurable difference to child well-being”

Shelley Phipps and Peter Burton are big names in this area.

Frances: thanks for the info about marriage penalties. A quick Google search turned up this thread:

http://www.canadianmoneyforum.com/showthread.php?t=2173

In particular, the GST credit and the Canada Child Tax Benefit are calculated based on household income, not individual income.

Someone on the thread mentioned that for the most part, Canada’s tax system is based on the principle of family-formation-neutrality: “tax systems should not encourage or discourage particular family forms.” I wonder how much it would cost to remove the marriage penalties for the GST credit and CCTB.

“I’ll tell you what the “division of labour” view of democracy is: not. “You don’t worry your pretty little heads about it.”

Exactly. The duty of the people is to express their opinions on any given topic so that the politicians may listen. When we hold an election we hold them responsible.

Elections after confidence votes are an explicit appeal to the confidence of the people.

It is the job of parties to be the machinery that links the popular will to the policy of the government, in conjunction with the Public Service. Every cabinet minister and the Prime Minister all have partisan, political advisors and Public Service advisors and advice is provided to the Minister/PM by both.