Financial advisors seem to be everywhere this time of year, pontificating about the merits of Registered Retirement Savings Accounts (RRSPs) and Tax Free Savings Accounts (TFSAs).

I'm not a financial advisor, but I know a bit about how the tax system works, and can do some basic arithmetic.

The most important difference between RRSPs and TFSAs is that with RRSPs, money is taxed when it comes out, but with TFSAs, money is taxed before it goes in.

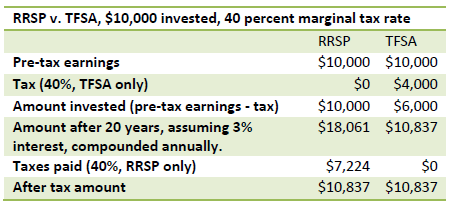

RRSPs and TFSAs provide identical returns when a person's tax rate doesn't change over time. The table below calculates the returns to investing in an RRSP and a TFSA for someone who always pays a 40 percent marginal tax rate, and has $10,000 in before tax income to invest.

If this hypothetical individual puts the full $10,000 in an RRSP, she pays no taxes (for now), and can invest the entire $10,000. If she puts the money into a TFSA, she has to pay income taxes on her $10,000 before investing it. Thus has only $6,000 to invest – that's the downside of TFSAs.

Over time the money compounds. Then, eventually, there comes a day when the funds are withdrawn. This is where RRSP owners have a nasty shock: all withdrawals from an RRSP are included in income, while TFSA withdrawals are tax free.

Some basic arithmetic shows that, if a person faces the same tax rate throughout her life, it doesn't matter which she chooses, the RRSP or the TFSA. At the end of the day, she will have exactly the same amount in her pocket.

The amount after 20 years is calculated as amount invested multiplied by 20 years of interest payments, for example, 10,000*(1.03)20.

The amount after 20 years is calculated as amount invested multiplied by 20 years of interest payments, for example, 10,000*(1.03)20.

For people who expect their marginal tax rates to fall in the future, however, an RRSP is a better investment. Consider, for example, a person who faces a 40 percent tax rate when the funds are invested, and a 25 percent marginal tax rate when the funds are withdrawn. For him, an RRSP generates a higher after-tax return, as shown in the table below:

Income in an RRSP is taxed when it comes out, so if a person expects to face a low tax rate during that withdrawal period, RRSPs are a good investment option.

Income in an RRSP is taxed when it comes out, so if a person expects to face a low tax rate during that withdrawal period, RRSPs are a good investment option.

Conversely, if a person expects to face a high tax rate in the future, TFSAs are a better choice. The next table compares the returns to RRSPs and TFSAs for a person who faces a 25 percent marginal tax rate now, and a 40 percent marginal tax rate in 20 years time.

For a person who is currently in a low tax bracket, TFSAs are generally a good choice.

There are a few other considerations to bear in mind. Funds invested in an RRSP can be used to finance a downpayment for a home. On the other hand, funds invested in a TFSA can be withdrawn in the event of a financial emergency, and then recontributed. However once money is withdrawn from an RRSP, the contribution room is lost for ever. Therefore TFSAs are more attractive for rainy day, shorter-term savings.

Bearing in mind the basic arithmetic of RRSPs and TFSAs, how does the commonly given financial advice stack up?

#1. "It's a complicated, difficult decision." Not really. It all comes down to marginal tax rates now and in the future. So, for example, for a childless single person or household earning under $40,000 a year, a TFSA will almost always be a better investment, because a person in that income range might well be eligible for Guaranteed Income Supplement upon retirement, and GIS packs one heck of a marginal tax rate. High income earners, on the other hand, should usually max out their RRSPs before even thinkng about TFSAs.

There are a few caveats to this advice. RRSPs are worth considering for would-be homeowners. Child benefits (CCTB) can add significantly to a person's marginal tax rate, so the calculation is slightly more complicated for people with children – who also might want to consider RESPs as an option. Finally, even high income earners might want to take advantage of TFSAs for short-term saving goals. But TFSA for low income earners, RRSPs for high income earners is a good general rule.

#2 "Invest in an RRSP, and then put your tax refund into a TFSA." Perhaps this works psychologically, making it easier to save. But I don't think it's particularly good advice. Depending upon a person's circumstances, either a TFSA offers the greatest tax savings, or an RRSP does. It makes the most sense to max out the plan that's best for you, rather than contributing some money to both types of plans (except, as noted above, using TFSAs for short-term savings).

#3 "An RRSP is always a good investment." No. Just, no.

Here are some examples of situations where investing in an RRSP is a bad move.

- A 55 year old single woman has no savings, and income of $25,000 a year. Given these facts, the chances of her being eligible for Guaranteed Income Supplement upon retirement are reasonably good. Any money deposited into an RRSP will generate tax savings at a rate of about 25 percent, depending upon the actual provincial tax rate, but will reduce Guaranteed Income Supplement by $0.50 for each dollar withdrawn – plus she might pay income tax on the withdrawals also, for a total effective marginal tax rate of about 75 percent.

- A 20 year old student earns $10,000 in scholarship income, or receives a $10,000 bequest. Since these forms of income aren't taxable, an RRSP contribution will generate no immediate tax savings. Now the student does not have to claim the deduction for his RRSP contribution immediately, he could wait, say, 5 years until he is in a higher income bracket, and claim the deduction then. Given the average person's ability to keep track of deductions and credits year after year, this just does not stike me as a good plan.

A TFSA allows the money to grow tax-free right away. If the student wants to move the money over to an RRSP in the future, that is always an option – she will get back his TFSA contribution room. But once the money is in an RRSP, it usually can't be withdrawn without triggering tax liabilities.

It's a simple choice: taxes now, or taxes later. Pick the one that's right for you.

rabbit,

“It seems to me that the investment with the highest expected return should be in the TFSA, since you will not pay tax on those extra profits.”

Nope.

There’s absolutely no difference in the area of after-tax return, or risk management around that return, provided that entry and exit tax rates are the same.

The only thing to remember is that $ 10,000 of room and investment in an RRSP is equivalent to $ 6,000 in a TFSA, assuming a 40 per cent marginal tax for example. You’re investing the same after-tax amount of $ 6,000 in both cases. The economics of compounding and after-tax return are the same otherwise.

The effect of the government co-investment in your RRSP is that it generates the tax that would otherwise be payable on the return from a non-sheltered investment. And that’s the same as a tax-free return, which is what a TFSA gives you directly.

JKH: “The only thing to remember is that $ 10,000 of room and investment in an RRSP is equivalent to $ 6,000 in a TFSA”

But if – as is often the case – one is faced with $10,000 of room in an RRSP and $10,000 of room in a TFSA – two amounts which are, as you point out, not equivalent – then the high returns are better going in the TFSA, precisely because $10,000 in TFSA room is worth more than $10,000 in RRSP room.

Frances,

Yes, provided:

a) You have in excess of $ 6,000 of after-tax money available to invest in a tax sheltered vehicle (assumed here)

b) You are comfortable with the risk of more than $ 6,000 of high return investments as part of your overall portfolio mix of after-tax, tax sheltered investments (assumed here)

see your financial adviser

🙂

JKH – yup. Which illustrates an important point: all of this fussing about investments is pretty unimportant to the average Canadian, who is unlikely to have any funds for anything except for paying off student loans, saving for the downpayment on a home, paying off a mortgage, and putting their own kids through school until they’re 45, 50, or possibly much older.

Frances: indeed for most people, witness the fact that most contribution room goes unused, the only portfolio mix is mortgage and food. I am in the 20%, neither smoke nor drink. I have an 8 year-old car and yet I will catch up on my RRSP this year and begin my TFSA next fall.

JKH: for those who have a pension plan, would consider that as a risk-free asset that would change the composition of a TFSA or RRSP?

Jacques,

Old article on corporate bankruptcy risk to pension plans:

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/retirement/bankrupt-companies-pension-promises-destroyed/article1322007/

The wrinkle is that for a company that’s in good shape, a defined benefit plan provides benefits that are low risk relative to a defined contribution plan

But defined benefit plans are gradually disappearing

FW: “Russil – you raise a good point. There are similar issues with holding dividend-paying stocks inside an RRSP, i.e. it’s not possible to take advantage of dividend tax credits.”

True, and if you’re making less than $40k-odd, the dividend tax credit drives the effective tax rate on dividend income to zero. (On the other hand, that’s the same treatment afforded to dividends in a TFSA, and as others have pointed out, TFSAs and RRSPs are economically identical, except in terms of the timing of when you pay your taxes. I’ll have to do the math, but as with capital gains, I still think you’re generally further ahead to be earning dividends in an RRSP rather than in a tax-free acount).

On the other hand, with dividend paying stocks, the tax deferral advantage of an RRSP really matters (if your income high enough that you’ll pay tax on the dividends). At least with capital gains, there’s at least a theoretical possibility that you can just hold your stock for 40-odd year and defer the capital gain (and the tax thereon) until you sell it (so that, in substance, you get the same tax deferral advantage associated with earning income in an RRSP). By their nature, you can’t defer the recognition of dividend income outside of an RRSP.

The other big problem with holding dividend stocks outside an RRSP is that the mechanics of the dividend gross-up/tax credit generates “phantom” income that triggers OAS clawback (at least for some) on income that you never really have.

Jacques, I’d probably treat a private sector defined benefits plan as a form of senior secured corporate debt, which is basically what it is. If the plan is well-funded and the company is strong(i.e., your “debt” is secured by valuable assets and the “debtor” is solvent) that’s a low-risk asset. If the plan is poorly-funded and the company is weak, hey, it’s like holding a junk bond.

In theory, a public sector defined benefit plan (i.e., one actually backed by the government) should be low-risk (or at least as low-risk as any other government debt). On the other hand, governments can re-write laws and unilaterally amend the terms of your pension (just ask our Greek and Italian friends), companies can’t, so query if that doesn’t add a different element of risk. If you’re the beneficiary of an Ontario government pension plan, for example, I’d say that’s a riskier asset today than it was 5 years ago.

Sorry that should read: “I still think you’re generally further ahead to be earning dividends in an RRSP rather than in a TAXABLE acount”

It depends, Bob. Stocks inside an RRSP and RRIF do not benefit from the Capital Gains Exemption or the Dividend Tax Credit at any time. When sold and distributed out of the RRIF they can’t claim these items, they are taxed as regular income because they were never taxed in the first place. It’s the T portion of Exempt (on contribution), Exempt (during accumulation of returns inside plan), Taxable (in full, on distribution).

You can’t use an RRSP to defer dividend recognition like that, the entire sale price of the security (assuming it is distributed outside the plan) is taxable as regular income, no capital gains, no dividend tax credits.

Jacques Rene: “JKH: for those who have a pension plan, would consider that as a risk-free asset that would change the composition of a TFSA or RRSP?”

It depends upon the plan. Defined contribution v. defined benefit? How are the funds invested?

My understanding is that pension plans are typically required to keep, say, the percentage of the funds held in equities within some certain range.

If that range is not to your taste, you can use the savings from not smoking, drinking and running an 8 year old car to change your overall portfolio balance.

The original post made the point that, if tax rates are the same before and after retirement, then the same amount in a TFSA or a RRSP will give the same withdrawal amount. If this is true then, the tax deduction for capital gains or dividends makes the TFSA more interesting for the average person.

Other advantages of TFSA:

– OAS clawback reduced

– The average person probability of getting some GIS is increased

– More flexibility

– You can short the market

– No increased tax rate if one spouse die.

– All the money is available all the time.

The TFSA does not allow for recognition of capital gains or losses within the plan. The entire sum, like the funds invested in an RRSP, are Tax-Exempt during accumulation and exempt on withdrawal. TEE and EET, they are both E inside the plan and the TFSA is E coming out. If something isn’t taxable, there are no capital gains/losses to be recognized for tax purposes.

Frances:

“My understanding is that pension plans are typically required to keep, say, the percentage of the funds held in equities within some certain range.”

It depends in the case of DC pension. In Ontario DC pensions can be managed by a professional pension manager, which is in essence a mutual fund. This one fund in the plan does face “prudent investor” rules. But many DC plans, especially for smaller employers, are merely a selection of mutual funds (often sold by a life insurance company) with the selection left up to the contributor. The reason employers offer this sort of plan is ease for them and the fact that they can take advantage of vesting rules to recover employer contributions if the employee leaves, thus reducing their own cost.

The financial advice provided to mutual-fund menu DC plan contributors is usually perfunctory at best.

DC plans can range from well-funded near-DB plans with professional managers and excellent contribution percentages (15% combined) to miserable menus of mutual funds with high fees and very low contributions by the employer (1% employer per 1.5% of employee, maximum of 5% employer total for pay of $24K per year).

In short DC plans are very variable. Most would probably benefit from conversion to PRPP’s, simply due to the requirement for immediate vesting.

“Jacques, I’d probably treat a private sector defined benefits plan as a form of senior secured corporate debt, which is basically what it is.”

No, it’s junior, unsecured debt. This is not a point of economics but of law; this is why I say the Deferred Wages Theory doesn’t hold water. Under the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act and the Canadian Corporate Restructuring Act, actual wage arrears for the past six months are to be paid immediately, above secured debt and pension/RRSP contributions (but not liabilities) are included in this provision.

For a DB plan the crucial thing is the employer’s liability, as sponsor, to make up the actuarial deficit upon winding up of the plan. This liability is ranked as junior, unsecured debt at law and as such pensioners who have a DB plan that is wound up will very likely take a big haircut. Note that only Ontario has a pension-protection fund and that is only available to single-employer plans. Multi-employer plans (most of the big ones, actually) are not protected. The other provinces and the Federal jurisdiction have no pension protection at all.

The NDP has proposed revisions to the BIA but banks and investor groups are loathe to share secured status with pension plans, reducing their share.

The unfunded pension liabilities are junior, unsecured debt is why I say it is impossible to get money from a dead man, aka a bankrupt company. See Nortel.

Also see this site for a good description of the ranking of creditors (never mind the politics): http://www.carp.ca/2010/03/25/wayne-marstons-primer-on-the-prosed-act-bankruptcy-and-insolvency-act-and-other-acts-unfunded-pension-plan-liabilities/

“It depends, Bob. Stocks inside an RRSP and RRIF do not benefit from the Capital Gains Exemption or the Dividend Tax Credit at any time. When sold and distributed out of the RRIF they can’t claim these items, they are taxed as regular income because they were never taxed in the first place. It’s the T portion of Exempt (on contribution), Exempt (during accumulation of returns inside plan), Taxable (in full, on distribution).”

I don;t disagree with that description, but the favourable treatment of dividends/capital gains received in taxable accounts will often (and, I think, usually) not be enough to offset the advantage of being able to invest untaxed income in the first instance. True, the money coming out of the RRSP is taxed as ordinary income, but you’ll also have a lot more of it. What matters isn’t the amount of taxes you pay, but the amount of after-tax income you’re left with. In the example I gave above, I’d much rather pay a 50% tax on $20k of income, than a 25% tax on $10k of dividends/capital gains.

“You can’t use an RRSP to defer dividend recognition like that, the entire sale price of the security (assuming it is distributed outside the plan) is taxable as regular income, no capital gains, no dividend tax credits.”

Not quite. If I receive a dividend or realize a capital gain in my RRSP tommorow, I don’t pay any tax on that income/gain for a good 30 years or more. – in the meantime I can put that money to work earning more income. If I realize a dividend or capital gain in a taxable account, sure, it’s taxed at a low rate, but it’s taxed now, not in 30 years.

I think we are talking at cross-purposes, though I don’t disagree with your analysis. Dividends and Capital Gains connote specific tax treatments that don’t apply to RRSP’s or TFSA’s. I believe it is clearer to talk about returns [on investment] generally rather than specific forms of return. A dividend, a bond interest payment and a capital gain are all just returns on invested capital inside an RRSP since there is no income tax levied immediately nor is there any difference when the returns are taken out of the plan.

Since dividends and capital gains don’t get preferential treatment in RRSP’s compared to interest payments from bonds, RRSP’s are favourites of investors who love fixed-income securities (though you very likely know that Bob, I am simply stating it for the general audience to make a point).

Bob Smith: “Essentially an RRSP is a leveraged investment. You’re investing the government’s money (i.e., the $10k in taxes that you otherwise would have paid to have $10k in after-tax money), but you get to keep 50% of their share of the profit. Good deal – you won’t find many other silent partners willing to give you that kind of sweet deal.”

Excellent point — that’s a big advantage of RRSPs that I hadn’t been thinking about. (Of course, you still need to be able to predict what your future marginal tax rate will be.)

The usual advice I’ve seen is that if you want to hold both fixed-income and equity investments (say, a 50/50 allocation), don’t use a 50/50 allocation inside your RRSP and a 50/50 allocation outside your RRSP. It’s better to hold the fixed-income investments inside the RRSP, and the equity investments outside the RRSP.

Now I’m thinking that the RRSP investments should probably be given lower weight in your portfolio allocation, since you’ll still need to pay tax on them when they’re withdrawn.

“The usual advice I’ve seen is that if you want to hold both fixed-income and equity investments (say, a 50/50 allocation), don’t use a 50/50 allocation inside your RRSP and a 50/50 allocation outside your RRSP. It’s better to hold the fixed-income investments inside the RRSP, and the equity investments outside the RRSP.”

I think that advice makes sense on the assumption that you’ve maxed out your RRSP exemption. I.e., all else being equal, if you’re holding assets outside of your RRSP, it makes sense to hold the assets that are taxed at the lower rate (i.e., equities). I suspect a lot of financial advisors don’t appreciate the significance of that assumption.

In practice, I suspect few people are in that situation (i.e., how many people save enough so that their annual RRSP limit, and now TFSA limit,) binds? Given the surplus RRSP room out there, not many. In that case, if you believe that your tax rate will be roughtly the same or lower when you retire than it is now (and I suspect a lot of people in their prime savings years, say 40+, have some sense of what their future tax rate will be), I think you’ll generally be better off investing inside an RRSP than outside it, regardless of the whether your investing in debt or equity.

In terms of allocation, well, see above, I don’t think there’s any particularly compelling tax reason for making portfolio investments outside of an RRSP or a TFSA (other, perhaps, than the ability to deduct the interest on borrowed funds if the investment is outside the RRSP/TFSA, though personally I’d rather borrow the money interest free from the government in my RRSP) unless you’re one of the very small minority of people for whom the RRSP/TFSA (and if you have kids, the RESP) contribution limits bind. That said, people may have non-tax reasons for holding funds outside an RRSP/TFSA/RESP (liquidity, saving to start a business, kids private schools, emergency funds, etc.). Of course, those non-tax reasons may also drive you to a preference to investing in low-risk assets (debt) rather than tax-advantaged ones (equities)

On second thought, I can think of ONE good tax related reason for not holding a given investment in an RRSP (assuming RRSP limits don’t bind), namely if it isn’t a “qualified investment” for RRSP purposes.

That being said, Finance has aggressively expanded the definition of a “qualified investment” over the years so that, these days, pretty much anything that a retail investor might want to invest in (or would be allowed to invest in) is a qualified investment. And to the extent it isn’t, there’s no shortage of investment vehicles that are qualified investments that give you exposure to the underlying investment (for a fee, bien sure).

Two points never made above.

1) The tax rates you should use for evaluating contributions/withdrawals can only really be done by a calculation with and without the contr/draw. The $$ difference divided by the $cont/draw is the marginal rate. http://www.retailinvestor.org/RRSPmodel.html#taxrates

The tax rate for calculating the savings from tax on growth is your own marginal rate FOR THAT PARTICULAR type of income. http://www.retailinvestor.org/Taxburden.xls

2) The math for RRSPs should not be simplified, because then everyone thinks they know everything. The benefits from RRSP come from taxes saved on growth, changes in rates creating bonuses and penalties, the penalty for a delay in claiming the tax credit, and the effect of clawback of benefits that is usually measured within the tax rate calculation.

These are broken down in this spreadsheet that models a single withdrawal http://www.retailinvestor.org/Challenge.xls The total benefits (not broken down) are measured by the difference between the choices in this next spreadsheet that models withdrawals at the minimum. http://www.retailinvestor.org/OutorIn.xls