Economists frequently argue that taxing basic groceries is a good idea – for example, see these papers/posts making the case for taxing food in the US, Canada, and New Zealand.

The equity argument for taxing groceries is straightforward. Suppose everyone spends $500 a month on groceries. If groceries were taxed at 10 percent, everyone would pay about $50 in tax (or slightly less, if people cut back on their food expenditures when the tax is introduced). If part of the revenue raised by taxing groceries was used to give every low income individual a $60 tax credit, the tax on groceries would actually increase the well-being of the worst off members of society. Any additional revenues raised could be used either to decrease other taxes, leading to greater economic efficiency, or to provide needed social or infrastructure programs, further enhancing efficiency and/or equity.

This equity argument is the one emphasized in, for example, Michael Smart's recent paper. Yet it begs the question: why groceries? Why not increase the top rate of income tax instead, or raise capital gains taxes?

The heart of the economic argument for taxing basic groceries is that it increases economic efficiency.

There's a short version of the efficiency argument and a long version. The short version goes something like this: "If groceries aren't taxed, but other goods are, then people's choices will be distorted. They will substitute groceries for other goods, hence the economy will devote too many resources to producing food and too few to producing other goods. Economic efficiency will be compromised."

The short explanation is, on the surface, clear enough, but it begs as many questions as it answers. How do people substitute groceries for other goods? What does "too many" or "too few" resources mean? What is economic efficiency anyways?

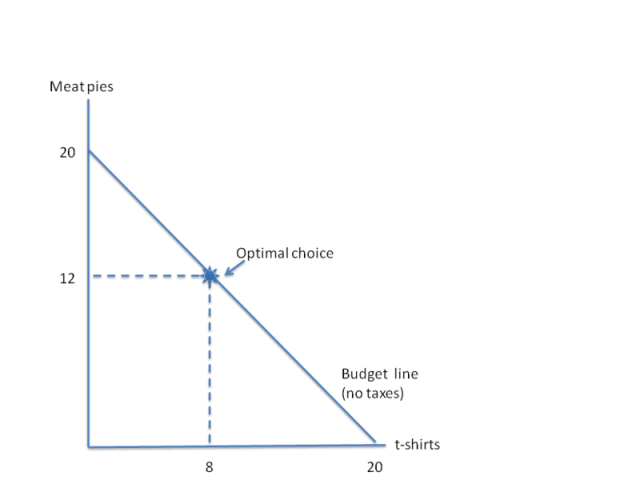

The standard undergraduate way of answering this question is with budget constraints and indifference curves. A budget constraint shows all of the different combinations of food and, say, clothing that a person can afford to buy. For example, if a person has an income of $200 a week, meat pies cost $10 each, and t-shirts cost $10 each, the person can afford 20 meat pies, or 20 t-shirts, or any other combination that costs $200, such as 10 meat pies and 10 t-shirts, as shown in the figure below.

No matter how constrained our circumstances, we always have choices. Economists assume that people choose the one point on their budget constraint that makes them happiest. In the picture below, that consumption bundle is shown as the "optimal choice" of 8 t-shirts and 12 meat pies.

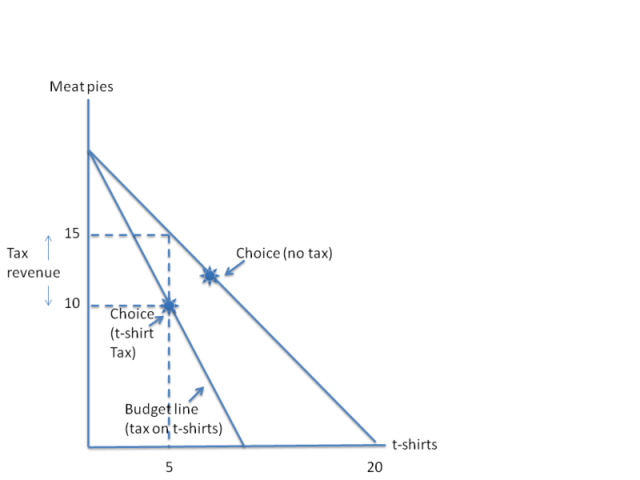

Under Canada's current sales tax regime, t-shirts are taxed, but not food. The tax on t-shirts changes the consumer's budget constraint, as shown in the next diagram. To exaggerate the effect of taxation, I've shown a 100% tax on t-shirts – one that raises the price of t-shirts from $10 each to $20 each. Now, if a person had $200 and spent their entire income on t-shirts, she would only be able to afford 10 t-shirts. Hence the budget constraint rotates as shown.

The consumer changes her consumption decisions in response to the tax. In this example, I've shown the consumer reducing her purchases of both goods, so she buys 5 t-shirts and 10 meat pies after the tax is imposed. The revenue from the tax is the amount of meat pies it takes away from the consumer. Prior to the tax, if the consumer bought 5 t-shirts, she could afford to buy 15 meat pies as well. After the tax, if she buys 5 t-shirts, she can only afford 10 meat pies. The revenue raised by the tax is thus 15 meat pies – 10 meat pies = 5 meat pies (or $50, since 1 meat pie costs $10). I've shown the revenue raised by the tax on the vertical axis, but I could also have shown it as the vertical distance between the new, after-tax choice and the original budget constraint. (Tax revenue in terms of t-shirts is measured horizontally.)

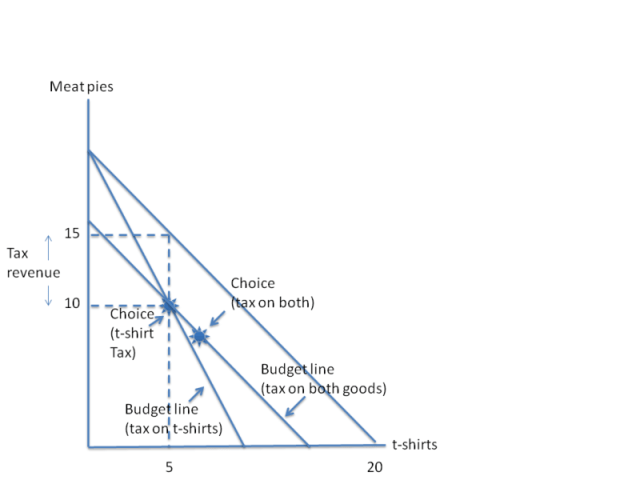

There are two ways to use this diagram to show that a tax on both meat pies and t-shirts is more efficient than a tax on t-shirts alone. One is to compare the tax on t-shirts with a tax on both t-shirts and meat pies that raises the same amount of tax revenue, and demonstrate that the later makes consumers better off. Revenue-neutrality could be achieved by lowering the tax on t-shirts when the tax on food is introduced, or by increasing refundable tax credits to compensate consumers for having to pay tax on food.

A revenue-neutral switch to a tax on both goods is shown in the figure below. It intersects the "Choice (t-shirt tax)" point because because raises the same amount of revenue as the tax on t-shirts only – taking the equivalent of 5 meat pies away from the consumer. It is parallel to the original budget constraint because the it reflects the same relative prices. The slope of the budget line shows number of meat pies a person can get in exchange for one t-shirt. It doesn't matter whether t-shirts and meat pies are both $10 each, or if there is a 33.33 percent tax raising the price to $13.33 each, a person can still trade one t-shirt for one meat pie.

The consumer's consumption choice after a revenue-neutral tax change is shown on the diagram below as "Choice (tax on both)." It has to be to the right of the original choice – when food is taxed, it becomes relatively more expensive and so, all else being equal, people will buy less food and spend more on other goods.

The crucial point is that the consumer is better off at the "tax on both" point than the "t-shirt tax" point, even though the revenue raised in the same in both cases. Take a look at the new, tax on both goods, budget constraint. That budget constraint would have allowed him to buy the bundle of goods marked "choice (t-shirt tax)", but he choose the bundle marked "Choice (tax on both)" instead. Therefore it must be a better bundle; it must make him happier than he was when he was consuming the t-shirt tax consumption choice.

Intuitively, the person is happier when both goods are taxed because he no longer has to modify his behaviour, buying t-shirts instead of meat pies, in order to avoid paying so much in taxes. That is the reason why economists think that taxing basic groceries is efficient – a tax on all goods will make consumer better off than a tax on just one good when the two taxes raise the same amount of revenue.

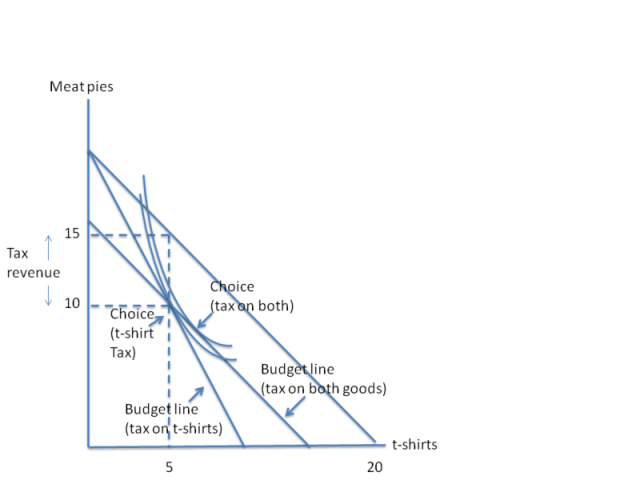

I have made the argument so far in terms of "revealed preference." Another way of making the same point is with indifference curves. Economists assume that everyone has an infinite number of indifference curves; these curves are like contour lines, tracing out a map of people's preferences. All points on a given indifference curve give the consumer the same amount of happiness; indifference curves further away from the origin – ones representing consumption bundles containing more stuff – represent higher levels of happiness. A person's optimal choice is the one that places him on the highest possible indifference curve, given his budget constraint. I have added indifference curves into the diagram here:

The consumer is on a higher indifference curve with the tax on both goods, than with the tax on just t-shirts, even though the revenue raised by the two taxes is the same, therefore he must be better off.

This is not, however, the only way of showing the efficiency of taxing basic groceries. Another way of showing the efficiency of taxing groceries is to show that a tax on both food and clothing raises more revenue than a tax on clothing only holding the consumer's level of well-being constant.

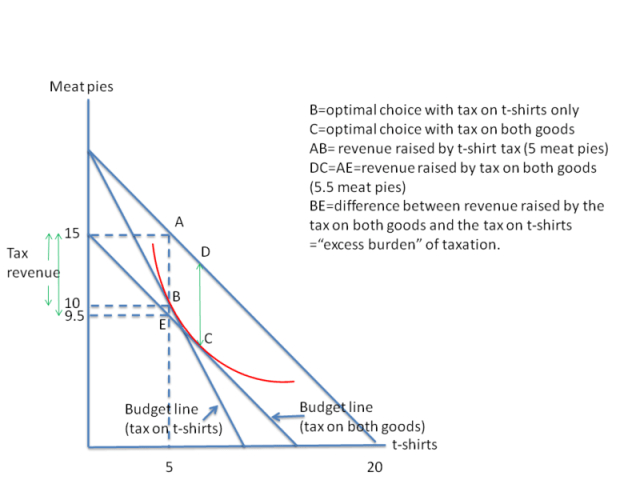

When there is a tax on t-shirts only, the consumer makes some consumption choice, shown as point B in the diagram below. This choice puts her on the red indifference curve. To keep the consumer's level of well-being constant, we construct a tax on both food and groceries that leaves her on that same, red, indifference curve. Again, we could do this by introducing a refundable tax credit just sufficient to compensate for the additional sales tax paid, or by lowering the rate of tax on t-shirts when the food tax is introduced.

This new tax-on-both-goods budget constraint is parallel to the original budget constraint, because it represents the same relative prices, and is just tangent to the new indifference curve, because it represents the same level of well-being.

With the tax on both goods, the consumer makes a new consumption choice, say point C. The movement from point B to C is called a "substitution effect"; the change in consumption choices associated with a change in prices holding well-being (or real income) constant.

The crucial point is that even though the consumer is indifferent between point B and point C, point C raises more tax revenue! The revenue raised by a tax is the vertical distance between the consumer's choice and the original budget constraint. The revenue raised by the tax on t-shirts is shown by distance AB (5 meat pies). The revenue raised by the tax on both goods is distance CD (equivalently, distance AE, or 5.5 meat pies). The difference between the two, distance BE, is the efficiency gains from taxing groceries.

When the case for taxing basic groceries is presented in these simple terms, the assumptions underlying the argument become apparent. The equation of choice with happiness rules out any paternalist arguments for exempting basic groceries from taxation. For example, at present soft drinks are subject to sales tax, but milk is not. A tax on milk would be expected to decrease milk consumption and increase soft drink consumption, all else being equal. Those who would argue for taxing basic groceries would respond in one of two ways: first, that we should respect people's choices whatever they are; second, so many of the basic goods exempted from sales tax at present are teeth rotting, IQ-lowering sugary junk anyways that the paternalist argument has little force.

Note that the advocates of taxing food cannot respond that substitution between milk and soft drinks is unlikely to happen. The efficiency gains from taxing food derive solely from the substitution effects, from people responding to price changes. It is contradictory to argue that "people won't change their shopping patterns when food is taxed" and, at the same time claim that there are efficiency gains from taxing basic groceries.

There are other assumptions underpinning the arguments for taxing groceries. They generally assume, for example, that markets are basically competitive, and goods are priced at marginal cost, so the primary impact of a tax increase is felt in the form of higher prices to consumers. It assumes, as just noted, that people substitute in a non-trivial way between basic groceries and other goods, such as restaurant food. Also, it assumes that the labour supply distortions created by giving people a refundable tax credit to compensate them for paying sales tax on groceries, and then taking that tax credit away again, are relatively unimportant.

Michael Smart's paper setting out the case for taxing basic groceries in Canada acknowledges these and other difficulties:

It is known that uniform taxation of all commodities is optimal only if all commodities have the same degree of substitutability with labour/leisure in preferences. [see the Ramsey rule] In highly stylized economic models, it can be shown that it is desirable to depart from uniformity by taxing more than average a commodity (like ski equipment) that is complementary with leisure. Nevertheless, a full, formal description of the optimal tax structure has eluded economists. An alternative approach is to study tax reforms that are desirable (though not necessarily optimal). Smart, building on the tax reform model of Ahmad and Stern, showed that a reform moving towards greater uniformity of tax rates increases economic welfare when consumers’ ability to substitute between taxed commodities is large, and ability to substitute between taxed commodities and leisure is small. The intuition is that taxing close substitutes at different rates creates tax avoidance opportunities that reduce government revenue and increase economic distortions of the tax system.

In spite of the theoretical ambiguities, for most commodities, uniform taxation is a reasonable benchmark for an efficient tax system.

Even the latest high-tech models of commodity taxation produce the same basic results as the simple indifference-curve budget constraint analysis, and for the same basic reason: the efficiency cost of taxation arise because consumers substitute one good for another in order to avoid paying so much in taxes, the most efficient tax system is the one that minimizes these substitution effects.

All I have is anecdotes. And I was about to relate them when I realized holy shit, these online merchants and ad networks must know a ton about people, if a corner store kid knows personal stuff.

Anyway I don’t know where you’d get data for the frequent/infrequent difference or if there is one, some people didn’t have bank accounts.

I suppose you could argue it’s like the patient kids in kindergarten. The more patient end up more successful. But I don’t know.

“I find this explanation, which starts with the premise that people aren’t entirely totally stupid, much more interesting.”

Not only is it more interesting, it’s also closer to reality. Drug addicts, to use K’s example, aren’t stupid when it comes to drugs. Quite the contrary, they know a heck of a lot more about the consequences than the rest of us (Often even before they become addicts they will have a significant knowledge of the realities of drug use. Anyone under the illusion that your average 9-year old in a US ghetto or on one of our aboriginal reserves knows a lot more about drugs and the consequences of taking them than (i)any of us, or (ii) by any rights, they should?).

And you’re right, the “not stupid” assumption is much weaker than the “rational expectation” assumption. Frankly, it’s hard to take serious any model that’s premised on the assumption that people are stupid, because at that point it ceases to be model and become a projection of the modellers ideological beliefs (i.e., if people weren’t so stupid (premise), they wouldn’t do drugs(belief), ergo, we should ban drugs (policy based solely on belief)).

With the kindergarten comment, I don’t want to argue paternalism. It would be hard for anyone to make a lump sum last a year, when your cost of groceries increases 10%. It should show up in a model, just like not having a bank account is rational due to the fees.

edeast,

But that’s the beauty of it, you can use extension of GST as a bargaining chip to cut income tax rates for low-income earners or increase income tax-free threshold. But of course, you can’t guarantee that tax cuts will be permanent or just bought forward, but then you can argue that for any policy.

DavidN: ” you can use extension of GST as a bargaining chip to cut income tax rates for low-income earners or increase income tax-free threshold.”

That really wouldn’t do a lot to help many low income households, because they don’t pay income tax anyways.

An increase in the income tax-free threshold of, say, $1,000 federally would provide a $150 benefit to everyone who pays a positive amount in income tax – so it’s somewhat progressive, but it’s very far from being the most progressive change that could be made in the tax/benefit system.

DavidN,

I also wonder about the merits of (effectively) increasing the GST (by taxing food) and using the revenue to either cut a tax that is, at best, a consumption tax.

Think of it this way, if you cut the bottom tax rate (or increase the threshold) it is a marginal rate cut for people who save very little (i.e., people in the bottom tax bracket) or a lump sum tax rebate for the wealthier (I.e., people in a higher tax bracket). In the first case, you’re just increasing one consumption tax (since for the poor income = consumption) and reducing another and in the second case you’re just giving a lump sum tax rate (which is probably the worst form of tax policy – akin to a permanent commitment to Klein bucks).

That’s the ironic point about the (very fair) Liberal criticism of the Tory GST cut – they forget that they were running in 2006 on the (equally silly) tax policy of cutting the bottom tax rate (very expensive in terms of foregone revenue, little upshot in terms on improved efficiency). It’s almost impressive that two mainstream political parties managed to fight an election on such a useless (from both an equity and efficiency perspective) concoction of tax policies.

Frances,

That’s true.

Bob,

I think it depends (on things I don’t know about e.g. elasticity of labour demand, opportunity cost of leisure etc.). If you reduce income tax because you extended the GST, labour increases (income increases), leisure decreases (which directly reduces utility e.g. through reducing family time etc.), also price of goods increase. So are you better off? But as Frances just pointed out, income tax cut or increase tax-free threshold for low-income earners is progressive but not as progressive as direct hand outs (but then as edeast noted direct handouts can lead to other issues…).

I don’t think I’m communicating, well. I think direct handouts are good, I’m arguing against getting a onetime tax refund. At least if its a onetime payout it should be at the beginning of winter so people could fill their oil tanks.

These are the anecdotes. One couple did cash the gst cheques,(our town doesn’t have a bank) and filled up their truck and jerry cans. (I’m inferring that that was their gas budget for the 4 months)

The milk comes in, as another couple couldn’t afford milk for their family, but did buy smokes.

Another couple would walk to the store, and buy groceries, they may have had a car but it wouldn’t have been street legal, the wife would come in with a welfare cheque, and pick up groceries, canned goods. It didn’t buy much. The husband would stay outside.

No social spending would help our town, but money would.

Also last anecdote, wrt drugs, I’ve met an ex? heroin addict, his wife cheated on him while he was out at sea, gave him aids. Heroin would look pretty good to me too. Plus there was some racial stuff.

Each of these are a lot more human, involved, and emotional than I’m letting on. Cause I didn’t want to engage in poor-people voyeurism.

But being a treeplanter I have met seasonal workers and heard stories of people who take advantage of ei. So that is everything I know, and I don’t know what is correct. I was just reacting to the income tax credit vs the income based tax credit.