The Association of Ontario Municipalities is having its annual conference August 19-22 in Ottawa, the mother city of all governments in Canada. Among the items on the agenda are the keynote address on: “new secrets to leadership with five powerful tools to improve negotiation effectiveness”, a speech by Ontario’s premier (followed by the opposition leaders the day after), and concurrent sessions of how to build a better school, fiscal sustainability of infrastructure and managing municipal risk. This is even a session called “Bring Back the Wild” which my councilors and city officials should find of interest given the recent spate of bear and alleged cougar sightings in Thunder Bay. And of course, my personal favorite is “The Beer Store: Your Partner in Economic and Environmental Success” sponsored of course by The Beer Store. What you won’t find on the agenda is a discussion of bureaucratic entropy.

In my latest trolling across the web, I came across a 1979 article in the Urban Affairs Quarterly titled “Economy of Scale or Bureaucratic Entropy? Implications for Metropolitan Governmental Reorganization.” The authors, John Hutcheson and James Prather examine the relationship between the number of city employees and city population. This study was done in an era when the fashion of the time was to implement metropolitan and regional city governments that consolidated jurisdictions. This often was justified by the argument that more efficiency and economy in service delivery would result. According to the authors:

“If efficiency can be defined as serving more residents with fewer employees, economies of scale might be demonstrated by a relative decrease in the size of bureaucracies as city size increases.” (Hutcheson & Prather, 167).

However, the authors found that not to be the case. Increases in the number of employees appear to have outstripped the growth in population in the wake of amalgamations and metropolitan reforms. The new institutions appear to have generated a dynamic which has resulted in less rather than more efficiency. They call this bureaucratic entropy. Essentially, the new institutions create a kind of disorder, which decreases the efficiency with which manpower is converted into service outputs. Or as they also write:

“Or more simply put, it could be easier to ‘goldbrick’ in a larger bureaucracy. Thus increasing city size may mean proportionately larger bureaucracies, and perhaps diseconomies of scale.” (Hutcheson & Prather, 168).

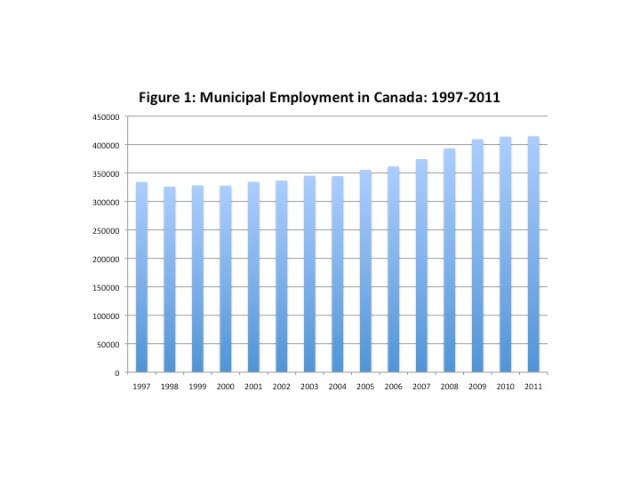

Well, naturally, I first decided to see if bureaucratic entropy was alive and well in my own community and the numbers indeed suggested that municipal employment has grown much faster than population in Thunder Bay. From 2001 to 2011, municipal employment in Thunder Bay grows by 25 percent while population remains stable. What about Canada as a whole? For Canada as a whole during this period, the number of municipal employees grew by 24 percent but population grew by 11 percent. (Figure 1) As the accompanying figure shows using data from Statistics Canada, from 1997 to 2011, the number of municipal employees grows steadily. The pace actually seems to pick up after 2006 leading one to wonder how much fiscal stimulus to combat the downturn ended up being dispensed at the municipal level.

So is this bureaucratic entropy? As municipalities were merged and new larger entities created, was the ultimate result the creation of monopoly municipal governments? Were bureaucratic structures put in place that do not keep costs in check? That may be part of the explanation but there is likely more to the story. Another explanation lies in the mix of city services, the demand for new services as well as changes in their quality. Municipal governments are expected to do more than they did in 1970 particularly in the areas of health and environment. Moreover, we are much richer than in 1970 and with rising income there is no reason why we would not want and pay for more municipal services, all things given. Tied to all of this is the fact that in Ontario as in other provinces, municipalities are creatures of the provinces and there is often the downloading of functions that necessitate new employment in order to comply with new regulations.

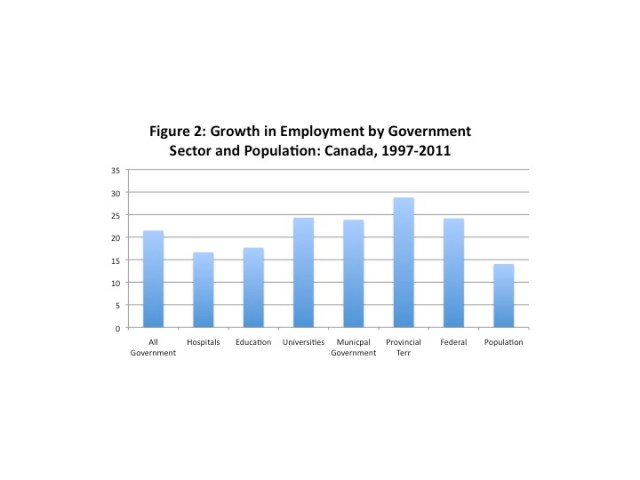

But then, this is not out of line with the employment growth across a variety of government related sectors. Indeed, they all grow faster than population with the greatest growth rates in provincial/territorial employment, followed by universities, then the Federal government and then municipalities. (Figure 2) So, is bureaucratic entropy in Canada real or a mythical beast? And, given our federal system, is bureaucratic entropy something that unites all levels of government as well as the broader public sector?

What numbers are you using. I’m looking at SEPH for fed/prov/local and getting 27/41/81 2011 over 1997.

At the municipal level, is another story the possibility that city mergers decrease inter-jurisdiction competition for taxpayers? With multiple jurisdictions, a government with large/expensive public service (at least relative to the services provided) risks losing taxpayers to nearby jurisdictions. Merge those jurisdictions, and you make it more expensive for taxpayers to vote with their feet (moving from the downtown Toronto to Forest Hill (then a separate municipality), in the 1920s, to avoid municipal income tax, not too painful. Moving from downtown Toronto to Richmond Hill, in the 2000s, to avoid property tax, much more painful).

It’s not quite on point (and its been a while), but I seem to recall Caroline Hoxby did some work on the impact of inter-jurisdictional competition on education outcomes (which the suggestion being that with more juridictions school boards had to keep quality up – though I gather that that paper has been the subject of heated bun fight with some of her peers. Mmmm, bun fights.).

I expect we are seeing the net results of: economies/diseconomies of scale; differences in productivity growth rates over time in services vs manufacturing; and income and price elasticities of demand. And causation could go both ways. Hard to disentangle, without some neat natural experiments.

“In my latest trolling across the web,…”

I thought/hoped that was a typo. But Merriam Webster told me it’s also correct for “trawling”. 😉

Hi Mark:

I like your numbers; they certainly would have made for a more dramatic post. I used CANSIM numbers, Series v52302855 to v52302864. I also did not include residential care facility employment in my numbers.

Bob: Thanks for the Hoxby reference.

Nick: Funny you should mention that. I used to think it was ‘trawling’ also but my kids keep using the term trolling – it seems to be a a reference to the internet they use.

In Livio’s defence, “trolling” is the usual pronunciation in Ontario for a perfectly innocent real-world fishing technique.

Livio:

There’s a good reason public sector employment has grown faster than population since 1997. In the late 1990s, overall public sector employment reached the lowest ratio it had been as a share of total employment (18.8%) or of population (11.3%) since at least 1976, when LFS figures are available from.

Since the late 1990s, public sector employment has increased as governments, hospitals, schools, municipalities and colleges and universities too (as I’m sure you are aware!) have tried to restore the services cut during the the 1990s — and at the municipal level in Ontario there was of course a lot of downloading from the province. I think this growth is a response to demands for more and diverse public services. At the municipal level we now have not just garbage, but also recycling and composting. We also have more community services and recreational services than when I was younger, serving the needs of families where both parents work. When polled a majority of Canadians have invariably expressed a preference for increased public services over tax cuts.

Even now, following stimulus spending and slow growth in overall employment, the ratio of public sector to total employment is 20.6% (average in 2011) — lower than the average since 1976 and still lower than it was in any year prior to 1996 in the LFS stats.

Even the Globe’s libertarian columnist Neil Reynolds, in a rare ideological lapse, recently acknowledged the magnitude to which the size of government had shrunk in Canada.