The little-known microeconomics textbook Zowning and Bupan does an excellent job of presenting the case against medicare vouchers:

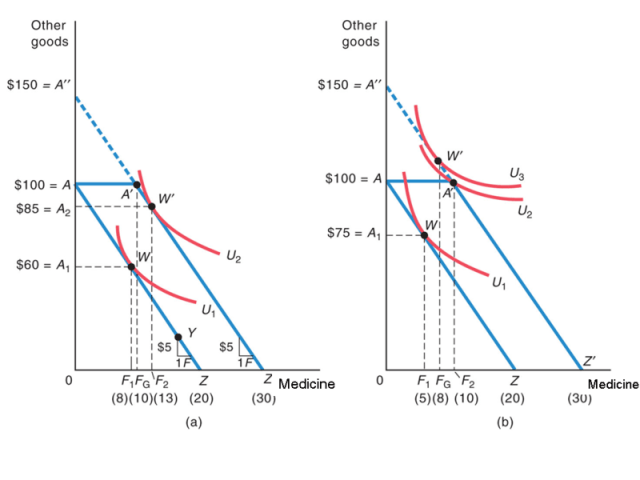

Consider the figure below. The pre-voucher budget line is AZ, and the consumer's choice is shown by point W.

The medicare voucher will affect the recipient in one of two ways. Figure a shows one possibility. In this case, the consumer chooses market basket W' when the budget line is AA'Z' under the medicare voucher program. If the consumer receives instead a cash grant of equal value, the budget line is A"Z', and the same market basket W' would be chosen. Consumption of medical care increases, but only because medical care is a normal good, and more of a normal good is consumed at a higher income. Note, however, that medical care consumption rises by less than the amount of the subsidy. For the preferences shown in Figure a, medical care consumption increases by 5 units. The consumer uses the remainder of the subsidy to increase purchases of other goods. (Because other goods, taken as a group, are certainly normal goods, too, the purchase of these goods will also increase).

Figure b, where the indifference curves differ from those of Figure a, shows another possible outcome of the medicare voucher. In this case, with a direct cash subsidy, the consumer prefers to consume at point W', where U3 is tangent to the budget line A"A'Z'. The medicare voucher prohibits such an outcome, however; the consumer must choose amount the options shown by the AA'Z' budget line. Faced with these alternatives, the best the consumer can do is choose point A', because the highest indifference curve attainable is U2, which passes through the market basket at point A'.

When the situation shown in Figure b occurs, the voucher increases the consumer's purchases of both medical and non-medical items. Indeed, regardless of whether Figure a or Figure b is the relevant case, the medicare voucher cannot in reality avoid being used in part to finance increased consumption of non-medical items. This result is particularly interesting because many proponents of subsidies of this sort emphasized that the subsidy should not be used to finance consumption of "unnecessary" goods (such as vodka or junk food). In practice, it is difficult to design a subsidy that will increase consumption of only the subsidized good and not increase consumption of other goods at the same time.

Note also that the consumer in Figure b will be better off if given $50 to spend as he or she wishes instead of $50 in medicare vouchers. This observation illustrates the general proposition that recipients of a subsidy will be better off if the subsidy is given as cash. The situation in Figure a illustrates why there is a qualification ot this proposition: in some cases the consumer is equally well off under either subsidy. THere is no case, however, when the consumer is better off with a subsidy to particular good rather than an equivalent cash subsidy.

There is no Zowning and Bupan textbook. I just changed "food" to "medical care" and "food stamps" to "medicare vouchers" in the analysis of food stamps in Browning and Zupan's intermediate microeconomics textbook. Actually, Browning and Zupan provide a spirited defence of vouchers in the 11th edition of their text, arguing that they would be more efficient than President Obama's health care reforms.

It's a pattern repeated in some other economics textbooks (e.g. Harvey Rosen's widely used public finance text). Where a good is presently publicly financed or provided, as is the case for medicare or elementary education, the text argues for the superiority of vouchers over public provision or finance. Where a good is provided through vouchers, as is the case for food stamps, the text argues for the superiority of cash transfers over subsidies. Where cash transfers exist, the text shows that the high effective marginal tax rates implicit in tax/transfer programs reduce work incentives.

Not every economics text argues for minimal government, and not every economist believes in it. But those who do are unlikely to stop arguing for smaller government just because a few government provided services have been replaced with vouchers.

Haven’t gone through all the comments, but isn’t it a bit unrealistic to assume that there is a choice in how much medicine one consumes.

I thought one has to buy the medicine doctor’s prescribes (I am talking in terms of quantities without additional complications of price of medicine in terms of other good).

Two pointes:

1. I would assume that the elasticity with respect to medicine is 0 (perfectly inelastic).

2. The comparison should be modeled based more on Leontiff type of diagram in one good (medicine). A person enjoys other goods only if he has minimum health (i.e. at least a minimum amount of medicine).

reason – you’ve identified a key reason why private monopolies can be worse than public monopolies.

Abhay – the movie Sicko contains many inaccuracies, but if you have a chance, watch the first ten minutes of it. There’s a very nice example that shows that the demand for medicine is not perfectly elastic – a person who was told “you can save your 4th finger for $20,000 and your middle finger for $60,000”. He chose to save his fourth, but not his middle finger.

Determinant,

“Ryan has stated that he is an adherent of Austrian Economics.” ah I see, so I was correct. It’s just he didn’t like the technical term I used to describe him.

Oops – I forgot the smiley with that. –)

“The employees of a public monopoly may try to do the same, but then at least politics, and institutional structures (e.g. ombudsman) may counteract them”

Although the same could be said of private monopolies being controlled by politics and institutional structures (think regulation in the telecomunications industry or of utilities). IThe difficulty in both cases is the (in)ability is that the monopolists generally have better information about costs than the regulators.

As an aside, why don’t we consider the employees of a public monopoly to be private monopolists. Generally their union, a private organziation whose sole purpose (and raison d’etre) is the advancement of its members interests, has a monopoly on the provision of those public services. It ties in nicely with Frances’ other post on framing. Generally, providing a private entity with a monopoly on the provision of public services would be abhorent, but call it a union, and people will go to the barricades to defend it. In that light, maybe McGuinty should have spun the wage freeze he’s imposing on teachers as price regulation of a monopolist.

Bob Smith: A a labor organizer ( one component of my Ken Kesey whole), we try to instill professionalism and sense of duty to the public amongst our public service members. A private monopolist would not do that.

Public service ethos exist. Private ethos is the one Adam Smith tried to counteract.

Bob Smith

“Although the same could be said of private monopolies being controlled by politics and institutional structures” ..

well yes that is an alternative. But are all private monopolies regulated? And yes there are difficulties in differences in information about costs – but they can also be exaggerated. What was that line about the price of liberty and vigilance?

P.S. In case anybody is interested, I thought of a good way of explaining the various schools of economic thought in charicactures involving maps and territories:

A saltwater economist will often confuse the map with the territory.

A freshwater economist will insist that his map IS the territory.

A post-keynesian will question whether maps contain any useful information about the territory.

An austrian will insist that the territory can only be known by interpreting the cryptic writings of their holy prophets.

“we try to instill professionalism and sense of duty to the public amongst our public service members”

Keep trying. Look, there’s no doubt that there is a a “public service ethos” (part of which is “That’s not my job”). But the notion that members of the public service don’t act in a manner to maximize their private interest is both illusory and a recipe for lousy public policy (every time I hear a teacher’s union explain that they’re going on strike or working to rule for the sake of the children I want to barf).

I’m a big fan of Julian Legrand’s work challenging the assumptions behind the motivations of public servants (no knucle dragging neo-con he, he was an advisor to the “new” labour government in the UK). His point was that the traditional assumptions, that public servants are motivated by a “public sector ethos”, by a form of altruism, leads to exploitation of the public by those same workers. No doubt public servants (or at least some of them) may have altruistic motives, but they’re not saints, they have self-interest like everyone else (to deny that is to deny their humanity). In Legrand’s words, they’re not knights, but knaves (or, at least, have knavish-qualities).

“But are all private monopolies regulated?”

Generally, yes. And to the extent they’re not reguled explicitly, they’re subject to the application of the Competition Act. More to the point, the same people who are enraged by the Ontario governments regulation of private monopolies in the public sector – i.e., imposing contracts on teacher’s unions – (and , let’s be clear, that is a private monopoly enforced by public policy) are the ones who are the most zealous about regulating private monopolies. That’s the disconnect that I can’t wrap my mind around.

Bob: Public sector workers are no saintlier than those who, by pure randomness, work in the private one. But ideological training may convince you that your ethos is part of your compensation. Soldiers don’t kill for money ( only criminals and mercenaries do and everybody knows the distinction) and they don’t die for money (criminals never do and mercenary do it only by accident).

New Labour might not be neocons but their contempt for people at large may have been even worse. That Tony Blair was a sanctimonious nominalist may be part of the explanation.

“Public sector workers are no saintlier than those who, by pure randomness, work in the private one.”

My point exactly. So why are private monopolies bad, while private monopolies in the public sector are good?

Public sectors workers are the same as private one, including the deputy minister who long for a bigger limousine. But, unlike, those in the private sector, especially managers, they are not taught that their prime duty is to steal everything in sight.

A doctor who performs an unnecessary procedure will be shamed by(ok a dwindling as we have put the market values in service professions)) number of his colleagues. A bank president will get a bonus and be named Man of the year. As well as “doing the work of God” and be a job creator…