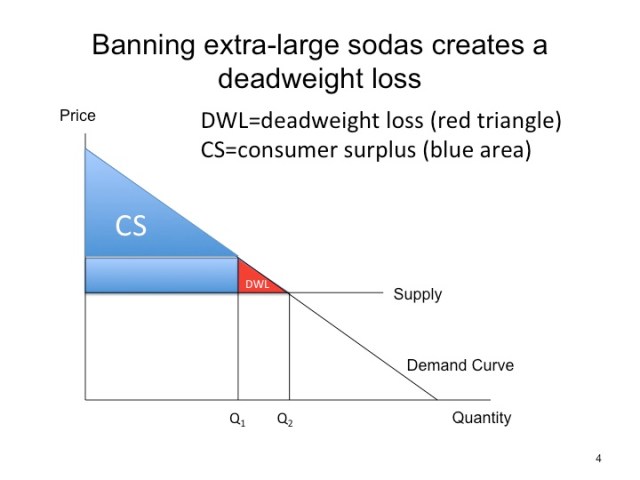

Anyone who has taken Econ 1000 learns that restricting soda consumption creates a deadweight loss:

At the price shown, consumers would like to buy Q2 units of soda. A ban on extra-large sodas restricts their consumption to Q1 units. At point Q1, consumers would like to buy larger sodas, and firms would like to supply larger sodas, but they are not allowed to. The resulting loss in consumer surplus – the benefits consumers enjoy from consumption – is called a "deadweight loss", and represented by the red triangle above.

Analysis of deadweight loss is a very simple type of "welfare economics" – the study of how projects and policies affect people's well-being, or welfare. Implicit in standard welfare economics is the assumption that people know what is in their own self-interest, and act upon it. If people drink extra-large sodas, it must be because the enjoyment they get from drinking sodas outweighs the costs, for example, weight gain and increased risk of diabetes. Unless soda drinking harms other people, any analysis that begins with the premise that people's actions are based on rational self-interest must inevitably reach the conclusion that soda bans reduce welfare.

Behavioural economics, however, calls the basic premise of rational, self-interested choice into question. As Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein argue in their book Nudge, people often don't make the effort of thinking through their decisions. Instead, they resort to "mindless choosing." For example, one experiment gave participants bags of five-day old stale popcorn, and then showed them a movie. Even though though the popcorn was "like eating Styrofoam packing peanuts", people ate it anyways – and the people with large bags ate more, even though they didn't particularly like the popcorn in the first place.

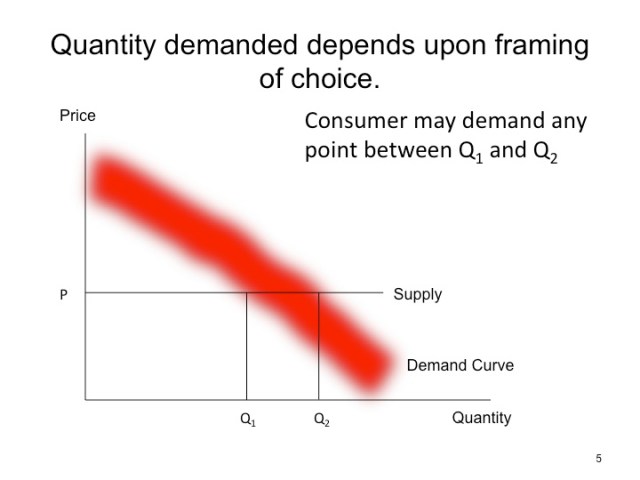

If behavioural economists are right, perhaps extra-large sodas don't really give people more happiness than slightly smaller ones. Consumer demand, seen through the lens of behavioural economics, looks more like this:

People are not totally devoid of sense; they cannot be persuaded to buy just anything. But, at any given price, a consumer might be persuaded by buy any quantity between Q1 and Q2, depending upon how the consumption choice is framed, or marketed. Any quantity within this range could be the observed outcome of a "rational choice" at the price shown. In this world, a soda ban simply nudges the consumer from point Q2 - grabbing an extra-large soda – to Q1 - grabbing a large soda.

Yet this begs the question: how does the behavioural economist know which is better, Q1 or Q2? Sometimes, as in the case of sodas, the behavioural economist urges consumers to consume less. But when it comes to, say, savings, behavioural economists work in the other direction, creating nudges that get people to save more. But how does a behavioural economist know which direction the consumer should be nudged in?

One possibility is to replace the old tools of welfare economics – consumer and producer surplus – with health and happiness. Does drinking less soda increase health? Are people who drink smaller sodas happier, all else being equal, than people who drink extra-large ones? If so, then the ban may be good policy.

Health and happiness are not the only metrics by which behaviouralists judge choices. Thaler and Sunstein, for example, argue that each of us has an internal planner, a sensible person who would like to make rational choices, but who is defeated by our internal Homer Simpson. In this view, the behaviouralist is just helping us do what our inner planner would like. Yet how do we know what people's inner planners really want?

While I am sympathetic to behavioural economics, I worry about the consequences of viewing all policies through the lens of health. Some of the best things in life are also somewhat dangerous – like swimming across a lake with only the moon and stars for company. At the same time, I want to live in a world where I'm nudged towards healthy choices – where it's easy to get around by bicycle, for example, and the university cafeteria serves reasonably nutritious meals.

Welfare economics teaches us to respect people's choices. Behavioural economics urges us to protect people from making dumb choices that they'll regret later. I don't know of any way of resolving these two views.

To be clear: when soda creates a negative externality, restrictions/taxes on soda are welfare improving. There is no contradiction between traditional welfare economics and behavioural economics.

The conflict between welfare economics and behavioural economics only gets interesting when we’re talking about behaviours that cause self-harm – smoking in some isolated wilderness spot, reading fmylife.com even though it makes you feel sad and depressed, etc. (And please let’s not get into the “I suffer when other people hurt themselves by smoking” debate – smokers contribute so much to the well-being of others by paying taxes and dying before they have a chance to collect much by way of pension plan payments – plus as long as they die fairly quickly they don’t cost the health system much).

That was an episode of “Yes, Prime Minister”.

Frances

A useful post. A further point might be that any extended division of labour progressively removes both the ability to rationally form preferences and the ability to express them. In other words, the division extends to the range of choice available, the ability to know all the factors relevant to choice, and the ability to actually choose. So the more you trade, the less you can have preferences. An example might be my preferences for how safe the buildings I use are: I cannot know how safe they are, I cannot know (in most cases) how safe they could be at what cost, and anyway the choice has been removed from me to building code regulators, builders and so on. Even with the soda – I can choose size, but I can’t choose the ingredients, or know how they are made ( I can and do often read the fine print, but I can’t be sure it’s telling the truth, I can’t understand what all the chemicals do and so on without spending time and money that I can better spend on other things). I realise this doesn’t help you salvage micro choice theory.

The economics view that people know what’s best for themselves is inherently a problem. Humans are still an animal, governed by our instincts (“gut feelings,”) and a herd mentality. When we step back from the problem, we can make a rational analysis of our choices, but actually making rational choices every day is not just really hard, but probably impossible.

Economics tells us a lot about why people act the way they do, and how to influence people’s daily choices in a direction that decision makers have determined is preferable, but I think the attitude that economics can tell us anything about just what the ideal choice is is hubris on the part of economists. People are known to, as a group, place disproportionally little value on the future, yet economists treat this as a rational decision instead of an evolutionary leftover of being able to reasonably plan on snuffing it by the time we reach middle age. So consuming more sugar today is similarly treated as a rational choice instead of behaviour hardwired by our ancestors environmental conditions that no longer apply.

Those who are willing to step back and look at the problem from the perspective that maybe we don’t always know what’s best for us can come up with policies that will make not only our overall society better off, but very possibly most of the individuals within that society better off as well.

Or looked at in another facet, classic micro assumes that information is costless and the ability to process that information is also without cost or limit. Behavioural Economics, OTOH, posits that information-processing is costly and time-limited. Macro had a similar debate between Hayek and Keynes over whose system was more “general”. Keynes assumed costly information, Hayek used cost-free information and processing.

Any engineer will tell you that placing limits on processing ability drastically affects the outcome and the strategy chosen to reach it.