Tiff Macklem is senior deputy governor at the Bank of Canada. On Friday, Tiff gave a speech on "Flexible Inflation Targeting and 'Good' and 'Bad' Disinflation". The Bank of Canada is not like the Fed; Tiff's speech reflects the Bank of Canada view.

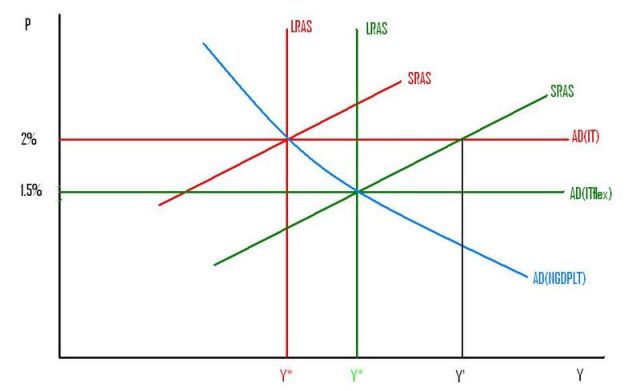

The picture below reflects what I think Tiff might be saying:

Real GDP is on the horizontal axis, and the price level is on the vertical axis.

Look first at the red lines only. The intersection of the three red lines represents equilibrium in an economy with no shocks. There is no output gap (Y=Y*), and inflation equals the 2% target. (Imagine the intersection point of those 3 red lines trending slowly upwards at 2% per year, and trending slowly rightwards at the natural/potential real growth rate.)

Now let's hit the economy with a real shock. The retail sector suddenly becomes more competitive. There is a once-and-for-all drop in the average level of monopoly power in the economy. This shock causes the LRAS curve and SRAS curve to shift to the right. But does it cause the LRAS and SRAS curves to shift right by the same amount? That is the key question.

If the shock causes both LRAS and SRAS curves to shift right by the same amount (not as shown), the Bank of Canada should stick to targeting 2% inflation (stick to the red AD curve), so that actual output increases by the same amount as potential output and there is no output gap.

But if the shock causes the SRAS curve to shift right by more than the LRAS curve (as shown by the green curves), then sticking to the same 2% inflation target causes a positive output gap, because Y' would exceed green Y*.

I read Tiff as saying that the Bank of Canada believes that the real shock of increased retail competition has caused the SRAS curve to shift right by more than the LRAS curve, and that the Bank of Canada's response will be to temporarily cut the inflation target. If the Bank gets everything exactly right, the economy will be at the intersection of the 3 green lines (I made up the number 1.5%).

An alternative policy would be to replace Inflation Targeting with NGDP level targeting; replace the horizontal red AD(IT) curve with a downward-sloping (rectangular hyperbola) blue AD(NGDPLT) curve.

In my diagram, flexible inflation targeting and NGDPL targeting lead to exactly the same results. But the first gets those results by the Bank following discretion, and the second gets those results by the Bank following a rule.

Now, it is true that I rigged my diagram to get exactly the same results under NGDPLT as under flexible IT. In general, those 4 curves would not all intersect at the exact same point. NGDPL targeting would only keep the output gap at exactly zero if the SRAS curve had exactly the right elasticity and shifted by the exactly right amount relative to the LRAS curve. But then flexible inflation targeting would only keep the output gap at exactly zero if the Bank of Canada's estimates of that elasticity and relative shift were exactly right too.

But, by recognising the difference between "good" disinflation and "bad" disinflation, and saying that inflation targeting should be flexible enough to reflect that difference, Tiff is implicitly acknowledging one of the central arguments for NGDP level targeting: it handles real shocks better than inflation targeting.

But the question remains: why should a real shock cause the SRAS curve to shift right by more than the LRAS curve? The answer depends on the nature of the nominal rigidity. For example, if wholesale prices were sticky, but retail prices were set as a markup on wholesale prices, where that markup is a negative function of elasticity of demand (the degree of retail competition), then this is what we would expect to happen. If nominal wages were sticky, but prices flexible, we would get similar results. But if retail prices were the only sticky prices, we would get different results: the SRAS and LRAS curves would shift right by the same amount. It all depends.

In my opinion, strict NGDPLT will be imperfect but beats strict IT, simply because real shocks will typically shift the SRAS curve by much more than the LRAS curve. And so flexible IT would be worse than flexible NGDPLT, simply because the former would require more "flexibility" than the latter. And if there is no (reputational) cost to "flexibility", why have any explicit target at all? The sensible question to ask, because it does not have an obvious answer, is: would flexible NGDPLT beat strict NGDPLT?

Vincent, you might try your question on Lars Christensen: he does a lot of articles on emerging markets and in fact Argentina is one of his frequent article tags (he has a list of click on in the right hand column):

http://marketmonetarist.com/category/argentina/

Also there’s this from Lars, which kind of ties into the Say’s Law discussion above:

“However, in Real Business Cycle models money are assumed to always be neutral – both in the short and the long run. I fundamentally think that is completely crazy and all empirical evidence is telling us that money is certainly not neutral i the short-run. Keynesian and monetarists (and even Austrians) agree on that, but the Real Business Cycle theorists do not agree. They basically think that recessions are a result of people suddenly wanting take have very long vacations (ok, that is not what they are saying, but it is fun…)”

So maybe you’re not an Austrian… maybe you’re an RBCer at heart. What do you think?

Vincent, obviously I’m wrong to categorize you as an RBCer: you never claimed that money is perfectly neutral in all time frames: you claim that FRB, paper money, etc cause us to deviate from that neutrality (as best I can tell).

Anyway, I think there are two big flaws with the NGDPLT idea.

1) Hyperinflation can hit suddenly. As one person puts it,

the Fed thinks they are dialing a thermostat up and down

but really they are playing with a nuclear reactor where

a wrong move can cause a chain reaction making the whole

thing melt down.

2) When the government needs money the central bank always

helps them out. If they did not want to then the rules, laws,

and people would be changed till they did, or the government

and central bank would fail together.