In the tradition of the fur traders of the Northwest Company, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities is holding their board meeting “Rendezvous” at the head of the Great Lakes in Thunder Bay from March 5th to 8th. It was difficult task trying to find an agenda on their website but no doubt they will be discussing the shortage of infrastructure funding as well as how their needs are not being addressed. Municipalities in Canada have been busy rebutting the perception that they are doing well given increases in property tax rates and increases in grant revenues.

The Canadian Federation of Independent Business has borrowed from the marketing efforts of Scotiabank with a report titled Municipalities are Richer Than They Think. The CFIB report argues that municipalities are overstating their woes when they claim that cities only receive eight cents out of every tax dollar collected given that they also receive grants from the provinces and federal governments, which they do not include in that figure. The CFIB says their share of Canadian government revenues once adjusted for this is closer to 15 percent. They point out that the total real per capita revenues for municipalities have grown substantially over time and their real operating spending has grown much faster than population.

The municipalities are naturally incensed and have responded that:

“The report neglects to mention that transfers from other governments can be taken away at any time and often require matching funds from local governments for projects that may or may not match local priorities. Our communities simply cannot go on asking local taxpayers to pick up the bill, especially when user fees and our property tax system are especially hard on families, seniors, and other middle and low income Canadians. Beneath all the CFIB’s spin, nothing in its report changes the simple fact that only 8 cents of the taxes Canadians pay are collected by local governments, while the other 92 cents are collected by federal, provincial, and territorial government…The fact is that federal and provincial governments have a monopoly on all the taxes that grow with our economy, including income and sales taxes, while local governments are forced to rely on a 19th century property tax system to pay for local services and any costs other governments choose to offload.”

Well, the municipalities are right in that the Federal and Provincial governments have a dominant position within the Canadian tax system but that is a result of the Canadian constitution, which makes them creatures of the provinces. Making them an equal partner with the other two levels will require constitutional change. Simply handing over new tax powers from the provinces at their discretion in a sense will be no different from the current situation whereby the transfers “can be taken away at any time…” Of course, engaging in constitutional change is a lot of work and the municipalities would simply prefer more money.

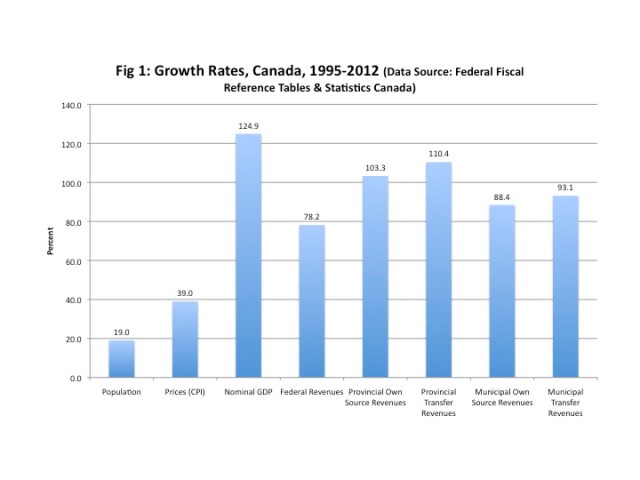

Should they get more money? Well, lets take a look at the revenue picture. The accompanying figure (Fig 1) plots the total percentage revenue growth for federal, provincial-territorial and local governments over the period 1995 to 2012. As well, the revenues for the municipal and provincial fiscal tiers are divided into both own source and transfer revenues. These revenue numbers are from the Federal Fiscal Reference Tables. As well, for comparison purposes there are growth rates for Canadian population, prices (the CPI) and nominal GDP over the same period.

When one looks at the three levels of government, revenues have grown the most at the provincial-territorial level, followed by the local tier and then the federal government. As well, in 2012, total local government revenues made up 21 percent of total government revenues in Canada – that is an even bigger number than the one used by the CFIB. Remember, local governments do not just get revenues from property taxes and intergovernmental grants. They also have a wide range of user fees. However, municipal own source revenue is about 12 percent of total Canadian government own source revenues - another number which this time is between those used by the municipalities and the CFIB.

It should be noted that spending net of transfers to other levels of government has followed a similar pattern to revenues. Between 1995 and 2012, federal spending (net of grants to other tiers of government) rose 44 percent while provincial government spending (net of transfers to local tiers) rose 114 percent and local spending rose 99 percent. The balance of the federation has definitely tilted in favor of the provincial-local tier of government. Together, they account for 70 percent of spending net of grants to other tiers.

So why are municipalities complaining? Take a look at Figure 2. After a long run of increases, local government revenue growth is slowing. Since 2010, total nominal grant revenues for local governments have declined while own source revenue growth has slowed. Overall, total local government revenues in Canada have fallen from 148.9 billion dollars in 2010 to 146.7 billion in 2012. Yet, over the period 2010 to 2012, federal government revenues have grown from 231.9 to 253.4 billion dollars while total provincial-territorial revenues have grown from 348.9 to 372.2 billion dollars. Interestingly, while total provincial-territorial revenue is up, their own grant revenue is also down from 75 billion in 2010 to 72.6 billion in 2012. It may be that despite their overall revenue increases, the provinces are passing their own transfer reductions disproportionately down to the municipalities. On the other hand, if its a choice between reducing grants to muncipalities or health care – well, municipalities are going to get it.

So, while I think that municipalities could be doing more to getting their costs and spending under control, the fact is that the last three years have seen a revenue squeeze for local governments in Canada when it comes to their transfers. It hurts more given the expenditure increases that have been based on the healthy grant increases of the period prior to 2010.

// <![CDATA[

// <![CDATA[

// &lt;![CDATA[

// &amp;lt;![CDATA[

// &amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[

// &amp;amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[

// &amp;amp;amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[

// &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[

// &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[

// &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[

var sc_project=9080807;

var sc_invisible=1;

var sc_security=&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;4a5335bf&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;;

var scJsHost = ((&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;https:&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot; == document.location.protocol) ?

&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;https://secure.&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot; : &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;http://www.&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;);

document.write(&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;lt;sc&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;+&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;ript type=&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;#39;text/javascript&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;#39; src=&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;#39;&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot; +

scJsHost+

&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;statcounter.com/counter/counter.js&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;#39;&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;gt;&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;lt;/&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;+&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;script&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;gt;&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;);

// ]]&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;gt;

// ]]&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;gt;

// ]]&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;gt;

// ]]&amp;amp;amp;amp;gt;

// ]]&amp;amp;amp;gt;

// ]]&amp;amp;gt;

// ]]&amp;gt;

// ]]&gt;

// ]]>

// ]]>

I feel like using CPI as a baseline when it comes to government spending is a poor choice. When we talk about federal and provincial spending we talk about them as percentages of GDP, which I think makes far more sense. CPI is a useful index for consumers, but the things that governments buy are very different. A good chunk (top of head guess is “around half”) goes to paying for people, whether as outside contractors or internal employees. And if these people are going to see real wage growth, government spending on this portion of its budget is going to have to exceed CPI. If private sector employment has real wage growth, then in order to retain the same quality of employees, government wages must rise in step.

Even the portion of spending not spent on people isn’t very well tied to CPI. The “stuff” that cities buy a lot of – fuel (for buses, maintenance vehicles, police cars, etc.), concrete, asphalt, water, are purchased in vastly different proportions compared to consumer spending. For this reason, some cities maintain a municipal price index (MPI) to give their councils and citizens a baseline for what the baseline for maintaining current levels of service is. The City of Edmonton’s is at (http://www.edmonton.ca/business_economy/documents/City_of_Edmonton_MPI_2013.pdf), and is alway higher than CPI inflation, anywhere from 25% to 250% depending on the year. The fairest way to determine what a real increase in municipal spending looks like is by using a per capita number adjusted for MPI inflation.

You might still see some growth over the 1995-2012 even using a fair inflation definition. I don’t know what the ’90s were like elsewhere, but here they were disastrous for cities. Edmonton, for instance had a number of provincial responsibilities (ambulance service, social housing) downloaded onto it without any money to pay for it, and at the same time has a no tax increase (not even inflation-tracking) policy in place for a couple years prior to the 1995 baseline (1993-1997). There was also a much longer history of deferred maintenance that eventually came home to roost, and we’ve really only started the decades long process of catching up on that. There had too be some catch up at some point. Not sure if this applies at a national level, but I suspect there are similarities elsewhere.

Basically what I’m trying to get at is that the idea that municipal spending is not in control because it exceeds a the combined increase justified by population growth + CPI inflation over an arbitrary 17-year period is a ridiculous conclusion.

Neil:

Well the conversation has to start somewhere. Let’s try a different deflator – the Government Current Expenditure Implicit Price Index. Over the period 1995 to 2012 (by the way, its not that arbitrary a time range. The data in the Federal Fiscal Reference Tables for this comparison starts in 1991 and I wanted to look at finances after the effects of the recession and government restraint of the early 1990s) it grows by almost 60 percent. So you can make the case that “inflation” for all governments is higher than the CPI but even with this higher number, local and provincial government spending still rises a bit faster than population and inflation – that is real per capita spending has gone up. Local government spending has not gone up as fast as GDP meaning that as a share of GDP, municipal government spending is down – as is federal and provincial spending. Should municipal government spending be going up as a share of GDP because it is “more important” given the infrastructure deferrals of the 1990s? Well, just about every level and sector of government spending makes similar cases about their needs – I do not find municipalities unique there. As for Edmonton having its own municipal price index to make its case, I find that interesting. Edmonton may indeed may some unique factors or conditions that makes its expenses different from other cities but all cities can play that card. In my own city, whenever a comparison is published showing that its taxes or spending is out of whack with cities of similar size, the city politicians and administrators inevitably come out with the line that “apples are being compared with oranges.” Their point seems to be is that their city is “unique” and should only be compared to other cities when the outcome is favorable. One of the key problems with local government expenditure comparisons in Canada is that municipal finance data is diverse, generally hard to get and not always that transparent – something I believe a CD Howe Report looked at some time ago. In terms of my conclusions, I think my main point was that local governments are complaining because their transfer revenues are indeed down. Their total revenues are down when revenues at the other two levels are up. I think they have a legitimate point here that does not appear to have gotten them much media attention as they have done a poor job of making this point in the media. Local governments are so busy comparing apples and oranges that they often miss the view of the orchard. As for doing more to get their spending under control – yes, they could. All governments can always do more to spend taxpayers money responsibly.

On the expenditures side, it would be (ahem) worthwhile to compare growth in opex, capex, transfer pmts to individuals, and debt payments over this period, by level of gov’t.