That's the equilibrium condition for the real rate of interest in a competitive economy. I will explain what it means a little later.

This is intended as a simple "teaching" post, and because I have a strange feeling that the theory of interest and capital is becoming topical again in the blogosphere, and that a post like this might be helpful.

Suppose you had a competitive economy that produced and consumed both apples and bananas. How would you explain what determines the equilibrium relative price of apples and bananas? This is how I would do it.

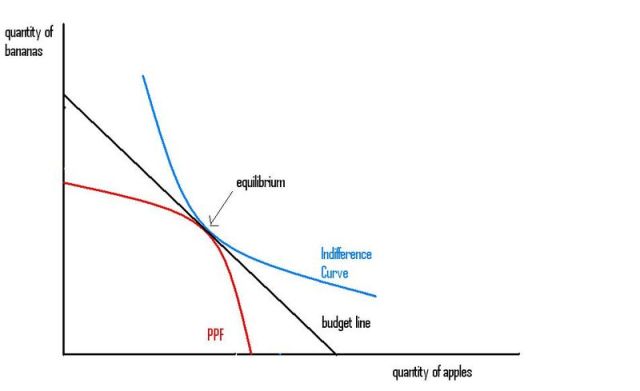

I would draw a simple diagram like this:

The red Production Possibilities Frontier shows all the combinations of apples and bananas that can be produced given resources and technology. The slope of the PPF represents the Marginal Rate of Transformation of apples into bananas: how many extra bananas can be produced if you produce one less apple.

The blue Indifference Curve shows all the combinations of apples and bananas that give the consumer the same level of utility. (There is a different indifference curve for each level of utility, but I have only drawn one.) The slope of the indifference curve is the Marginal Rate of Substitution of apples for bananas: how many extra bananas would you need to consume to give the same level of utility if you consumed one less apple.

The black budget line shows all the combinations of apples and bananas that can be bought or sold for the same level of income. The slope of the budget line shows the relative price of apples in terms of bananas: how many extra bananas you can buy or sell with the same income if you buy or sell one less apple.

In competitive equilibrium, where producers are maximising profits and consumers are maximising utility, and demand equals supply, all three curves have the same slope. The equilibrium condition is:

MRSab = Pa/Pb = MRTab

The relative price (and the quantity of each good) is determined both by the PPF and by the indifference curve(s). You need both to explain prices.

Only in special cases do you not need both. Like if the PPF was a straight line you don't need the indifference curve to explain relative prices. Like if the Indifference curve was a straight line, you don't need the PPF to explain prices. (But even in these cases you need to look at the other curve to check you aren't at a corner solution where only one good gets produced and consumed). Or if one of the two curves is kinked, so its slope is undefined at that kink, so only the slope of the other curve determines the relative price. (But even in these cases you still need the kinked curve to tell you where you are on the other curve.)

OK. That's how I would explain what determines the relative price of apples and bananas. (If you want to add carrots to the model, just add a third dimension to the diagram.)

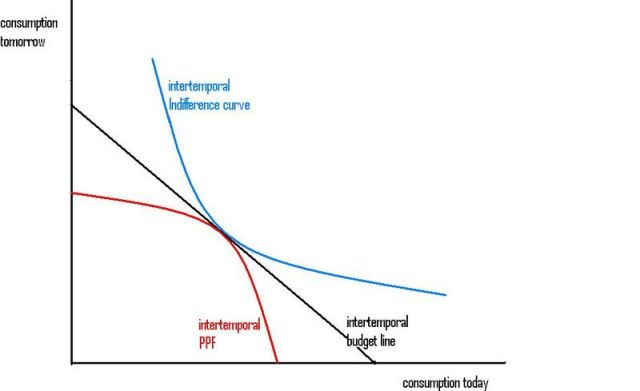

Irving Fisher used basically the same diagram to explain what determines the competitive equilibrium real rate of interest.

The only thing different between the two diagrams is what's on the vertical axis. Instead of a trade-off between apples and bananas, we have a trade-off between apples today and apples "tomorrow" (or next year). The slope of the budget line is (1+r), where r is the real rate of interest (the nominal rate of interest, minus the inflation rate on apples). If r=5% per year, if you consume 100 less apples today you consume 105 more apples next year.

We now interpret the slope of the indifference curve as the Marginal Rate of intertemporal Substitution, between consumption this year and consumption next year. Call it MRScc.

And we now interpret the slope of the PPF as the Marginal Rate of intertemporal Transformation, between consumption this year and consumption next year. Call it MRTcc. The equilibrium condition is:

MRScc = (1+r) = MRTcc.

If you want to add a third time period, just add a third dimension to the diagram.

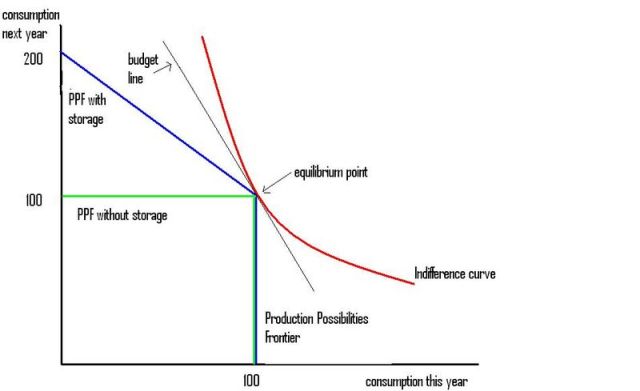

Here is an example of a special case of the Irving Fisher diagram, where the PPF is kinked.

The economy can produce 100 apples each year. The green PPF assumes you cannot store apples from one year to the next. The alternative blue PPF assumes you can store apples from one year to the next. (If 10% of the stored apples rotted, you would need to replace my "200" with "190", and if 100% of the stored apples rotted you get the green PPF). In this example, people choose not to store apples. But the equilibrium rate of interest is still determined in this example. It is determined by the the slope of the indifference curve at the kink. The slope of the PPF is undefined at the kink. If we wanted to, we could complicate this simple model by having different people with different preferences. More patient people would lend apples to less patient people, at a positive rate of interest, but no apples get stored.

We don't need "capital", or its marginal product, to determine the rate of interest.

But let's go back to the more general case of the Irving Fisher diagram, where the PPF is curved. Where is "capital" in this model? And where is the Marginal Product of Kapital? Does MPK determine r? Does MPK=r? "No", is the answer to both those questions.

The equilibrium condition is MRScc=(1+r)=MRTcc. MPK is one of the things, but not the only thing, that affects MRTcc. And MRTcc is equal to (1+r), but it does not determine (1+r).

Suppose that the economy can produce capital goods ("investment" is the quantity of capital good produced each year) and consumption goods. There is a PPF between consumption and investment, just like the PPF between apples and bananas in my first diagram. The slope of that PPF is the Marginal Rate of Transformation between consumption and investment. Let's call it MRTci. In equilibrium MRTci=Pk, where Pk is the price of capital goods in terms of consumption goods. If the PPF is curved, like in my diagram, Pk will need to increase if we want producers to produce more investment and less consumption goods. And so we may not assume that Pk will be the same next year as this year, unless the PPF is a straight line, whose slope never changes from one year to the next.

And if you want two different capital goods, just draw a 3-dimensional PPF.

MPK is defined as the extra apples produced per extra existing machine, holding technology and other resources constant, and holding the production of new machines constant. If we move along the PPF between consumption and investment this year, we will have a bigger stock of capital goods next year, which will shift out next year's PPF. MPK tells us how much it shifts out, per extra machine.

What is the relationship between: MRTcc (the slope of the intertemporal PPF); MRTci (the slope of the consumption-investment PPF); and MPK?

This year is year 0. Next year is year 1. The year after next is year 2. Suppose we consume one less apple this year. That lets us produce 1/MRTci(0) extra machines this year. That lets us produce MPK(1)/MRTci(0) extra apples next year. But it also lets us produce 1/MRTci(0) fewer machines next year, and go back to the same number of machines we would have had the year after next. And producing 1/MRTci(0) fewer machines next year lets us produce MRTci(1)/MRTci(0) extra apples next year.

So if we consume one less apple this year, we can consume MPK(1)/MRTci(0) + MRTci(1)/MRTci(0) extra apples next year. That is the slope of the intertemporal PPF.

So the equilibrium condition becomes:

MRScc = (1+r) = MRTcc = MPK(1)/MRTci(0) + MRTci(1)/MRTci(0)

Or, we could rewrite it as (where dMRTci/dt is the rate at which MRTci is changing over time):

MRScc = (1+r) = 1+(MPK/MRTci)+(dMRTci/dt)/MRTci

Or, since MRTci=Pk, we could write it as:

MRScc = (1+r) = 1+(MPK/Pk)+(dPk/dt)/Pk

If capital exists, the real rate of interest is equal to, but not determined by, the Marginal Product of Kapital divided by the real price of the machine, plus the capital gains from appreciation of the real price of machines. (The latter, of course, is only an expectation, which matters a lot in the real world. And all these models also leave out money, which also matters a lot in the real world, because bad monetary policy causes recessions, and recessions push the economy to a point inside the PPF.)

Rather than saying "MPK determines r", it would be more true to say "MRScc determines r, which determines the prices of capital goods". And the only thing wrong with saying that is that is that MRScc is not a fixed number, but depends on the expected growth rate of consumption, which in turn depends on our ability to divert resources to producing extra capital goods instead of consumption goods, and the productivity of those extra capital goods.

Or, we could even say that the central bank determines r, which in turn determines both the expected growth rate of consumption and the prices of capital goods. And the only thing wrong with saying that is that a central bank which sets r ignoring the equilibrium condition will really mess up the economy badly.

(Introducing physical depreciation of machines, so that new and old machines have different prices, is left as an exercise for the reader, because I will mess up the arithmetic.)

This post is also for Bob Murphy. Bob is really good on the theory of capital and interest, and already knows all this stuff and more, but he can't draw diagrams.

Nick,

“MPK is defined as the extra apples produced per extra existing machine, holding technology and other resources constant, and holding the production of new machines constant. If we move along the PPF between consumption and investment this year, we will have a bigger stock of capital goods next year, which will shift out next year’s PPF. MPK tells us how much it shifts out, per extra machine.”

Question: why am I not seeing an MPK function somewhere in here that is defined as the alternative of producing extra machines per extra existing machine? Isn’t that type of function also inherent in the transformation function? Or is it redundant to the required math?

O/T, Jason has an answer for your unresolved question Nick (the one for which you’re still in the “I don’t know” camp):

http://informationtransfereconomics.blogspot.com/2014/05/do-monetary-aggregates-measure-money.html?showComment=1399925805457#c4001174889208369862

Fascinating situation in California right now because of the drought. Cali produces 80% of the worlds tradable almond market. Almond trees require water (a decent amount four acre-feet). Other fruit trees are the same. The fascinating part though is that farmers are cutting back on the less water intensive crops in favor of the more intensive fruit trees which take years to mature but can be killed in a single year of not providing water. So water is this years capital investment. But new fruit trees would not be planted this year because they take many more years to bear fruit.

Lots of path dependence in the growth of the capital stock…

Kevin,

Not sure if you’re still checking this, but in regards to your blog post: You’re acting like it’s an unfortunate choice of terminology on Piketty’s part, that he uses MPK when he should be using MEC. But no, what he did makes perfect sense, if it’s legitimate to switch back and forth between “capital” meaning physical machinery etc. versus “capital” meaning a sum of money.

Because if we’re measuring capital as money, then the MPK = MEC. Do you agree?

(E.g. with physical machinery MPK might be 10 apples per additional hour of machine-time. But if we measure output and machinery in dollar terms, them MPK might be $10 / $200 = 5% = MEC.)

Bob,

I don’t think that works. The MPK is meaningful even in a one-period model. It’s just a partial derivative. But just to define the MEC we have to assume there’s more than one period involved.

Piketty writes very clearly for the most part, setting out his definitions early on and sticking with them. But that paragraph is a mess. Maybe there’s a way it could be rescued, but as it stands I think it should have a here-be-dragons warning beside it.

My mind is still on the farm in England!

JKH: “Question: why am I not seeing an MPK function somewhere in here that is defined as the alternative of producing extra machines per extra existing machine? Isn’t that type of function also inherent in the transformation function? Or is it redundant to the required math?”

It’s implicit/redundant. Let Kc and Lc be the amounts of machines and labour used to produce consumption goods, and Ki and Li be the mounts of machines and labour used to produce new machines (investment). let there be production functions C=F(Kc,Lc) and I=H(Ki,Li). If we assume Kc+Ki=K, and Lc+Li=L, (existing stocks of machines and labour are fully employed), we can derive a PPF between I and C just like we can derive a PPF between apples and bananas. (And unless F and H are identical functions, that PPF will generally be curved out rather than a straight line).

At any point on that PPF, there will be an MPK for C (=dC/dKc) and an MPK for I (=dI/dKi). And if competitive firms are maximising profits, the two will be related, like this: Pk.MPKi = Pc.MKPc = R where R is the rental per machine. And the slope of the PPF will be -MPKc/MPKi.

(In the above, I am assuming all functions are smooth, to keep it simple.)

Kevin, I thought that too at first, and it made me wonder if I (and Nick?) were being sloppy when saying r=MPK only under certain circumstances. Because if the dimensions aren’t even the same, then obviously r can’t equal MPK, period.

But then I thought about it more, and I think it works out; the sloppiness is in thinking that MPK is denominated just in units of output.

Look, we all agree that w=MPL right? Well the wage is a rate, or if we’re thinking in just output units, then we’re implicitly having a rate in mind.

And it’s also not right (as some people, not you, have suggested) that the interest rate is a pure number, because we usually mean “per year” at the end and just take it for granted.

Anyway Kevin there are all sorts of passages that have dragons flying around. In several spots Piketty is clearly discussing r as being due to the technological characteristics of adding machinery, land, etc. to production process. So it’s clearly MPK.

But then he talks about r influencing how fast financial capital grows, which is clearly an interest rate.

Nick:

“because bad monetary policy causes recessions”

Does bad monetary policy ever cause booms?

Bob: if we are talking about the use of capital goods to produce those very same capital goods, then MPK has the units 1/years. And if that MPK is independent of the age of the machine, so that employing one extra machine produces an extra flow of MPK extra machines per year, then the real interest rate on machines (nominal rate minus inflation rate on machines) will equal MPK. Probably the easiest way to think about it.

MF: Yes, probably. Good monetary policy will cause neither. Bad monetary policy will cause both. But booms and recessions don’t seem to be symmetrical. Milton Friedman’s plucking model seems to match the data closer than a symmetric model.

thanks Nick