Apparently, ten out of ten premiers (13 out of 13 if we count the territories) can agree that Canada is suffering from a “fiscal imbalance” between Ottawa and the provinces. At their annual meetings, which are wrapping up in Charlottetown today, the provincial premiers are arguing that since the Federal budget is moving into surplus (while the provinces and territories still have a combined deficit of $16.1 billion), its time for the federal government to boost transfers to make “significant investments “ in two areas – health care for an aging population and the nation’s infrastructure.

Two points here. First point. It is unfortunate the premiers like using the term “fiscal imbalance” to characterize a call for more money from the federal government because like the federal government has pointed out in its rebuttal, the provinces do not suffer from a fiscal imbalance. I am a bit of a traditionalist when it comes to the term fiscal imbalance. I use it to refer to the historic condition rooted in the creation of the Canadian federation whereby the provinces got the income elastic expenditures (health and education) and inelastic revenue source (direct taxation) while the federal government got income elastic revenues (any revenues whatsoever) and income inelastic expenditures (that is, not health and education).

As a result, the provinces were short of money for decades with their needs met by ad hoc grants. This was not resolved until the modern system of federal grants and transfers was implemented in the post World War Two era. As well, the provinces are no longer limited to direct taxation and have available to them pretty much all the revenue tools the federal government has with the key exception being tariff revenues (which are no longer significant). As a result, provincial revenues have been doing quite well and collective provincial-territorial revenues now exceed those of the federal government. Actually, they have exceeded federal revenues for quite some time now.

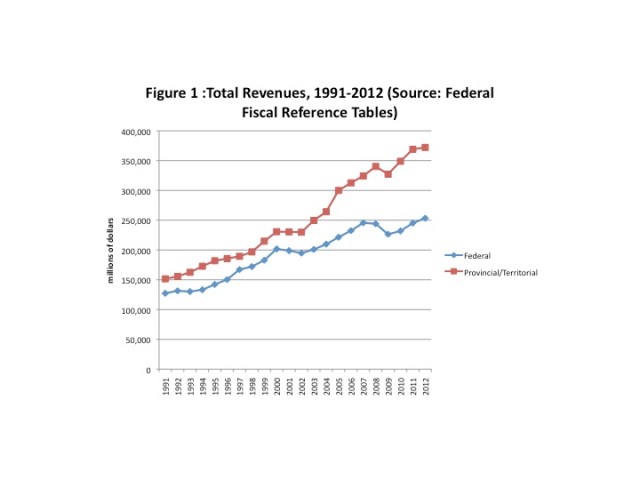

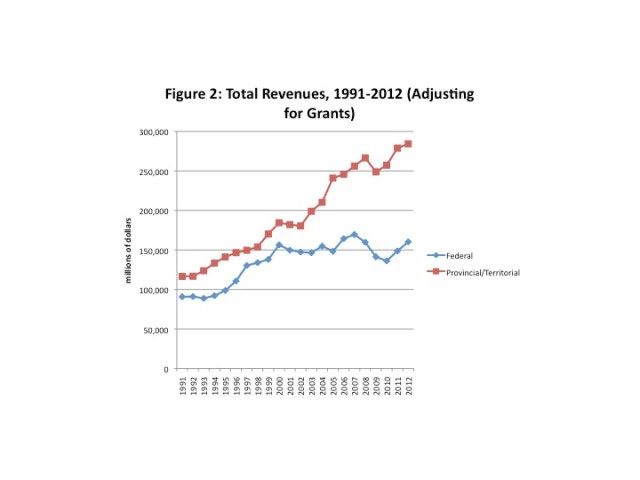

Figure 1 shows total revenues at the two levels of government without adjusting for any intergovernmental transfers. Figure 2 subtracts federal grants to other governments from federal revenues and provincial grants to other governments from provincial revenues to provide an estimate of revenues net of obligations to other levels of government. Needless to say, using either approach, there has been a growing revenue gap between Ottawa and the provinces – provincial/territorial revenues have been growing faster than the federal government. Between 1991 and 2012, total federal revenues grew 99 percent and provincial territorial revenues grew 145 percent (from Figure 1). Using Figure 2, federal revenues over this period grew 77 percent and provincial ones 144 percent. You might argue that the federal government weakened its revenue base via tax cuts over this period but it has been transferring a larger share of that total revenue to the provinces over time.

Second point. The premiers do have a point when they complain that the current federal funding formula for health transfers does not meet their needs. Population characteristics are becoming more diverse across the provinces and territories and health needs are tied to aspects of the life cycle like getting old. Some provinces have populations aging at a faster rate than others. The current per capita allocation is a crude mechanism and the federal government could do better when it comes to a more sophisticated design of the Canada Health Transfer. At minimum the CHT should be broken up into two components. First, a share based on a per capita allocation as is currently the case reflecting the fixed costs of running a public health care system. Second, a needs based share reflecting differences in population characteristics such as age distribution. For a more detailed look at some aspects of this issue, check out Marchildon and Mou in the latest issue of Canadian Public Policy.

Summing up. The provinces do not suffer from a fiscal imbalance. They suffer from wanting to spend more while having someone else pay for it. What else is new? Having said this, there are improvements that could be made to the current system of federal transfers to the provinces and territories. The federal government can do better than simply allocating health transfer funds on a per capita basis and then washing its hands.

// <![CDATA[

// <![CDATA[

// &lt;![CDATA[

// &amp;lt;![CDATA[

// &amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[

// &amp;amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[

var sc_project=9080807;

var sc_invisible=1;

var sc_security=&amp;amp;amp;quot;4a5335bf&amp;amp;amp;quot;;

var scJsHost = ((&amp;amp;amp;quot;https:&amp;amp;amp;quot; == document.location.protocol) ?

&amp;amp;amp;quot;https://secure.&amp;amp;amp;quot; : &amp;amp;amp;quot;http://www.&amp;amp;amp;quot;);

document.write(&amp;amp;amp;quot;&amp;amp;amp;lt;sc&amp;amp;amp;quot;+&amp;amp;amp;quot;ript type=&amp;amp;amp;#39;text/javascript&amp;amp;amp;#39; src=&amp;amp;amp;#39;&amp;amp;amp;quot; +

scJsHost+

&amp;amp;amp;quot;statcounter.com/counter/counter.js&amp;amp;amp;#39;&amp;amp;amp;gt;&amp;amp;amp;lt;/&amp;amp;amp;quot;+&amp;amp;amp;quot;script&amp;amp;amp;gt;&amp;amp;amp;quot;);

// ]]&amp;amp;amp;gt;

// ]]&amp;amp;gt;

// ]]&amp;gt;

// ]]&gt;

// ]]>

// ]]>

“As well, the provinces are no longer limited to direct taxation and have available to them pretty much all the revenue tools the federal government has with the key exception being tariff revenues (which are no longer significant).”

To clarify, the provinces are stil limited to direct taxation. But direct taxation includes the major tax instruments of the modern states, such as income, sales, value-added, etc. taxes. The original fiscal imbalance in the 19th century arose from the fact that indirect taxation – excise taxes, customs duties, etc. – where the principal sources of government revenue, while the heavy hitters in the direct taxation arsenal, notably income tax, where politically untouchable. Even then, the provinces have long worked out arrangements to get around this restriction, by deeming the intermediaries who are requred to physically pay the tax to the government to be agents of the crown, so that the taxes they “pay” are legallytaxes paid by the ultimate consumer and collected by the “agent” and remitted to the fisc (this is the basis on which, for example, Quebec levies QST – which is remitted to the fisc by suppliers, rather than consumers – and on which many provinces operate their fuel taxes).

With the advent of the modern income tax system in the 20th century, that “fiscal imbalance” issue was resolved.

The provinces need to grow-up and start taking responsibility for their own actions. There is nothing more embarassing than watching puportedly responsible leaders urging someone else to do their job for them. If they need more revenue, they should explain to their electorate why they need it, and raise more revenue, not ask another level of government to do it for them. That’s how democracy is supposed to work. Matching the spending of public fundswith the responsibility for raising it promotes accountability and good governance.

Indeed, the whole point of federal transfers was to allow the federal government to interefere in areas of provincial jurisdiction (i.e., health, education, social services). For some reason, the provinces think this is a good thing.

A case can be made for federal transfers to for equalization purposes – to your point – but beyond that the provinces should fund their own programs.

I think the point is not that there is a current imbalance, but that as reports from the Conference Board and the PBO have outlined, the projected costs/revenues/transfers into the future will create a huge imbalance.

I think the real issue is whether having the provinces substantially increase tax rates to cover the shortfall while the feds presumably lower theirs is the best approach or whether there is a case for continuing the current practice of the feds raising the money and contributing a given share (which would require a larger rate of increase of transfers than they’ve laid out).

“whilst increasing the political costs of revenue-raising. It’s no wonder that the premiers are pushing back and trying to shift the blame to Ottawa”

First, with the advent of the HST, the federal government is invariably going to catch some of the flak for any increase in the provincial portion of the HST (since its a tax levied by the Federal government, an increase in the provincial portion has to be enacted by Parliament).

Second, the real issue is not that the federal government is trying to increase the political costs of revenue raising (aka spending), but the provincial governments are trying to obfuscate that such spending has costs. “You want more health care”, they say, “if only the federal government would pay for it”, as if federal money just magically appears from thin air. The provinces want all the goodies of additional revenue, without having to bear the burden of obtaining it.

From my perspective, if Ontarians (for example) want to spend more money on, say, health care (or full day kindergarden, or green energy projects, or whatever), they should be making that decision while fully conscious of the cost of doing so. If that means they have to increase the provincial portion of the HST (for example) by 1%, if that spending is worth doing, it’s worth increasing the provincial portion of the HST 1% to pay for it. And if it’s not worth doing if you have to increase the provincial portion of the HST by 1%, why does it become worth doing if you have to increase the federal portion of the HST (say) by 1%.

Indeed, the HST as a revenue tool makes the absurdity of the Premiers’ position palpable. Since both levels of government jointly set the level of HST in a particular province (in the non-HST provinces, they’ve set it at 5%, with the provincial portion equal to zero), there is no particularly compelling reason for funding provincial spending indirectly, by increasing the federal portion of the HST, rather than funding such spending directly by increasing the provincial portion of the HST.

The provincial premiers are like Toronto politicians (minus the crack, booze and KFC), they’re big on new projects, but keen on getting someone else to pay for them.

“Most memorably, Flaherty was adamantly opposed to proposed increases in the Ontario corporate tax rate, and the criticism focused mostly on the raw level of taxation compared to its efficiency as a revenue tool.”

Yes, but Flaherty’s objection was premised on the inefficiency of the corporate income tax a revenue tool (it also doesn’t help that that inefficiency means provincial corporate tax increases undermine the federal corporate tax base), the tax level was just a mallet with which to hit the province. Note the much more subdued federal response when the Nova Scotia government increased the HST (a much more sensible tool for raising revenue). Of course, since Flaherty was one of Harper’s point people in Ontario and had a deep (and well deserved) loathing of the McGuinty government, that didn’t help either. Frankly, it doesn’t bother me when my federal representative dumps on my provincial representative when the latter does something stupid – that’s part of what makes federalism so effective.

I don’t care which level of government is cutting taxes, because all the others will raise taxes to fill the void, that’s what politicians and bureaucrats do. It must grate them that some of the masses still have disposable income, that’s just wasted taxing potential. Theses people love to dole out other peoples money to buy political power. I don’t trust any politician that wants to raise taxes specially specially when they rationalize it as good for social cohesion, the truth is they want to be re-elected and so the pander to people who prefer handouts.

“Let’s assume that Ontarians would prefer to have a balanced budget and the same amount of health care as currently provided. That’s reasonable, however the Federal government chooses to run a surplus.”

Is that a realistic scenario? After all, provincial voters are also federal voters. Granted, if you’re a resident of PEI, it’s probably fair to say that your preferences have no impact on the preferences of federal voters. I don’t think one can plausibly say that in respect of Ontario voters, given that they account for 1/3rd of all federal voters and that, given the unlikelihood of a Western/Quebec coalition, winning Ontario is essential for any party seeking power federally?

More to the point, is this plausibly a concern that ALL premiers share? Does no one in Canada vote for the federal government?

For the above scenario to exist, either voters have to have radically different preferences for spending/taxes at different levels of government (possible, perhaps, but not likely) or one level of government has to be completely out of touch with the preferences of their voters (also possible explanation, though in a more or less functional democratic system, not a long-term problem meriting new cost sharing programs). In any event, it’s not a description of the current reality since the federal government isn’t now running a surplus (well, it might be running a slight one, based on the recent fiscal monitor) and it has committed to devoting a significant chunk of any future potential surplus to tax cuts.

In any event, assuming that is potential outcome, that would tend to militate AGAINST federal transfers to fund provincial spending. If provincial/national spending/taxation preferences are that dramatically, it would make more sense to be making taxing/spending decisions at the provincial level where they can be better matched to provincial preferences. Indeed, that’s always been the argument for strong provinces within the Canadian federation, that it better matches distinct local preferences(notably in Quebec) with local powers.

As an aside, the Provinces might have one fair beef about federal tax cuts, notably the federal government’s commitment to reducing the income tax base, by increasing TFSA room. Since the provinces (outside of Quebec) are committed to using the federal tax base in their tax systems (reducing compliance costs for taxpayers, and making life easy for tax lawyers outside of Quebec), the effect of increasing TFSA room is to reduce the revenue of the Provinces. That’s not to say that increasing TFSA rooom is a bad idea, but it is one that dragoons the Provinces into cutting their taxes along with the feds, unless they take concrete (and politically damaging) action to not do so. If the Premiers weren’t such a bunch of whiny dolts, they’d use the threat of not following the federal lead on future TFSAs increases (in theory they can be non-taxed federally, but taxed provincially) to extract increased funding from Ottawa (that would be politically messy, but federal elections are next year, provincial elections in the big provinces aren’t).