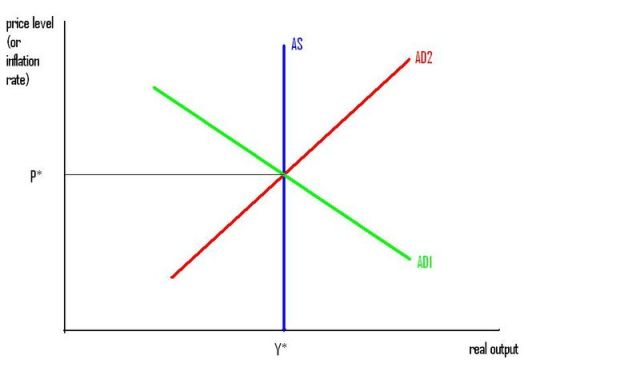

There are two different monetary policies. The green monetary policy gives you the green AD curve, and the red monetary policy gives you the red AD curve. Both monetary policies give you exactly the same equilibrium P* and Y*. (You can interpret P* as the price level, or as the inflation rate, as you wish.) Which monetary policy is best?

If you are an old economist, like me, you will probably say the green monetary policy is better. Because the red monetary policy leads to an unstable equilibrium.

If you are a young economist you will probably laugh at me for saying that. You will say that, according to the model I have presented on that diagram, both monetary policies are equally good, because they both create exactly the same result. And I cannot say whether either is stable or unstable from that diagram. I would need to say how the equilibrium evolves over time, in response to a shock to AD or AS, to be able to talk about stability.

When old economists talk about "stability", we are talking about departures from the model's equilibrium. When young economists talk about "stability", they are talking about movements of the model's equilibrium. Those are very different things.

Two different interpretations of the same word can lead to confusing arguments. One example is the "sign wars" controversy (if you have a model where the central bank's raising the nominal interest rate causes an increase in equilibrium inflation, is that a "stable" equilibrium?).

(Yes, these two views about "stability" are not perfectly correlated with age, or even vintage, but I think there is some correlation with age, and I need names for the two views, so "old" and "young" will be my names.)

What I am trying to do here is explain the merits of the old view.

But first I want to criticise the old view, to acknowledge that you young economists do have a point. Then I will try to explain why you should get off my lawn.

"Equilibrium" does not (necessarily) mean "quantity demanded equals quantity supplied". It simply means "that which the model predicts". (They only refer to the same thing in a model that assumes continuous market-clearning).

And that's central to the critique of the old view. If your model says that X* will happen, how can you talk about what would happen if X were different from X*? According to your model, X can't be different from X*. You are contradicting your own model. What you are doing is engaging in implicit theorising. Why not be explicit about it, and write down a new model, where the equilibrium in your new model can diverge from the equilibrium in your old model, and see how the equilibrium in your new model evolves over time? And throw away your old model, since you have already admitted your new model tells you what happens better than your old model does.

The old interpretation of "stability" was rejected by the same forces that created the insistence on formal microfoundations.

Now let me try to defend the old view.

We know that all our models are false; the only question is "how false?". Are they true enough to be useful, for the purpose we built them for?

We also know that our model-building abilities are limited. We cannot formally model everything we would like to model. Because formal modelling is hard. We sometimes make one assumption when we would rather make a different assumption, just because the first model is easier to solve. There are trade-offs.

We also know that our abilities to understand our own models are limited, and we want to be able to understand our models. Simplicity is desirable.

Models are just stories. We tell those stories using a mixture of words, diagrams, and equations. And stories leave things out. The whole point of a model is what it leaves out. A good model is one where the things it leaves out don't matter much for the purpose of the story.

In my diagram above, I have told two very simple stories. Those stories explain what determines the price level (or the inflation rate, if you prefer). Both stories tell us exactly the same thing will happen. The data cannot distinguish between those two stories. (They might appear to give different conditional forecasts if the AS curve shifts, but I haven't said how the AD curves would shift if the AS curve shifted, and I could rig the model so they make the same conditional forecasts.)

But I like the green story better than the red story, because it is more robust. The things that both stories leave out don't matter as much in the green story as in the red story.

Both stories leave out sticky prices. How much does this matter? It matters a lot more in the red story. Because if the red story is false, it will probably be very very false. If the price level is above what the red story says it will be, the red story says that will create excess demand for goods. And it is reasonable to assume that an excess demand for goods will cause prices to rise. Which makes the red story even more false. The green story says instead that there would be excess supply of goods, so prices will fall, and get closer to where the green story says they will be. So the green story won't be very false for very long.

We can ask how robust a model is with respect to parameter values. If the true value of a parameter is different from what the model assumes, will that affect the results much? We don't like knife-edge results for parameter values.

We can ask how robust a model is to any of its assumptions. We don't like knife-edge results for any assumption.

Old-fashioned discussions of stability were really informal discussions of robustness.

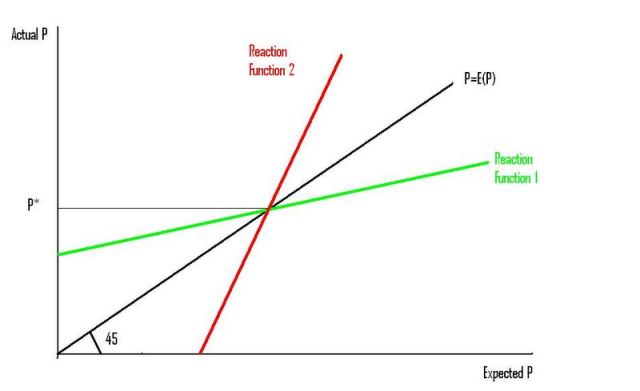

I could have presented a different example. I could have presented two different rational expectations models (or one rational expectations model of two different monetary policies), with the exact same equilibrium. Like this:

Both models make exactly the same prediction for the equilibrium price level. But I like the green model better. It has a "stable" equilibrium, in the old-fashioned sense. If agents do not have perfectly rational expectations, it is probable that they will still move towards the rational expectations equilibrium, under reasonable assumptions about learning. That makes it a more robust model. The red model is a knife-edge model. If firms expect the price level to be higher than the rational expectations equilibrium, the actual price level would be even higher than they expect. They will probably revise their expectations even further away from what the model predicts.

I can't always formally model learning. I can't always formally model sticky prices. I can't formally model tieing my shoelaces either. But that doesn't mean I shouldn't do it.

This may not be your intent but I associate the red line in both displays as being the AD line for boom examples in the early stage of the boom.

I associate the green line with monetarily stable (constant money supply) supply-demand relationships where more supply results in lower prices AND increased consumption (more potatoes results in a lower potato price so more people eat potatoes).

Both diagrams seem logical.

The next challenge is to decide where the AS and P=E(P) should CORRECTLY be placed. To explain, we built our model (both diagrams) with the expectation of general conditions; the red and green lines are general expectation of departure from stability assuming that the starting point is stable. Now it is very UNLIKELY that the present economic point is in a stable position, so, we must decide if the vertical AS line (the supply line) is (at present) following red curve conditions or green curve conditions. In the same fashion, we must decide if the P=E(P) line (at present) is following the red or green expectation model.

We can apply this model divergence to the residential construction period of 2007-8. Coming into the 2007-8 period, bankers and government seemed to be following the red line models. Then, suddenly, both bankers and government seemed to decide that they should be following the green line model. At that point in time, a considerable difference had accumulated between the expectations of the red and green models. There was a sudden adjustment to the whole economy as the dynamics of finance tried to adjust to the more accurate (in the long term) green line model. That adjustment seems to be continuing as we write.

I like the line of logic presented in this post. I wonder if can endure and expand?

Nick Rowe: “Equilibrium” does not (necessarily) mean “quantity demanded equals quantity supplied”. It simply means “that which the model predicts”. (They only refer to the same thing in a model that assumes continuous market-clearning).”

If nothing is equal in an equilibrium, then better to find a new term. 😉 But let’s grant the new definition. 🙂

Nick Rowe: “And that’s central to the critique of the old view. If your model says that X* will happen, how can you talk about what would happen if X were different from X? According to your model, X can’t be different from X. You are contradicting your own model.”

Excuse me. The are such things called time and error. Anyone who imagines that an economic model fit the data perfectly has a screw loose. And if the data deviate from the prediction of the model at any point in time, then the model should predict that the data should approach the prediction as time goes by, or it is not a prediction.

Nick Rowe: “When old economists talk about “stability”, we are talking about departures from the model’s equilibrium. When young economists talk about “stability”, they are talking about movements of the model’s equilibrium. Those are very different things.”

Indeed they are. Another word for “departure” is “error”, the difference between prediction and data. Another word is “perturbation”, errors which have causes that are not part of the model. It sounds like old economists paid more attention to concepts like error and perturbation than new economists. But without the concept of error, there is no prediction, there is merely assumption. So perhaps the new concept of equilibrium is not what the model predicts, but what it assumes.

Min: “If nothing is equal in an equilibrium, then better to find a new term. 😉 But let’s grant the new definition. :)”

Things usually are equal in a model’s equilibrium. But those things aren’t always quantities demanded and quantities supplied. Plus, it’s too late to change how we use the word.

Nick Rowe: “Plus, it’s too late to change how we use the word.”

Not that it is any of my business, but you have just said that the usage of the word has changed. Why should it not keep changing? (Or has its usage reached an, ahem, equilibrium? ;))

Let me add a point about stability, perturbation, and feedback. A system in which perturbations produce negative feedback is stable. Deviations lessen over time. A system in which perturbations produce positive feedback is unstable. Deviations increase over time. We have known since the 1990s that the solar system is unstable. But that is only in the long run. In the short run of tens of thousands of years, it is stable. Just because we can used the theory of gravity to predict the trajectories of planets in the solar system does not mean that it is stable.

A few more mathie points, I suppose:

*) A system is only stable or unstable if it has dynamics. Accounting identities describe what things are, not how things change. (MV = PY is an accounting identity; saying “increase the money base to increase the nominal output” is a dynamical story that makes assumptions about V)

*) Unstable does not mean unpredictable, as Min points out. But instability does limit “really long run” predictability. Theories which don’t constrain the price level are unstable over time even if they are predictable, since they’re consistent with P=1 or P=1 billion at infinity.

*) Models of a time-evolving equilibrium are useful if and only if that equilibrium is stable to perturbations

*) Models with stable equilibriums can be simpler, since they only need to show that the dynamics return to equilibrium and are less sensitive on how (or how quickly) things get back to “normal.”

*) Instability is harder, since you need a very short-term and detailed model of how things go awry.

*) The existence of business cycles suggests that the economy is weakly unstable. History suggests that the ultimate constraints are political, in that people will reject an economy that stops working too badly.

*) Proper control can turn an unstable equilibrium into a stable one, just like balancing a yardstick in the palm of your hand. Monetary policy is an attempt to do this with the economy.

Majromax: “Proper control can turn an unstable equilibrium into a stable one, just like balancing a yardstick in the palm of your hand. Monetary policy is an attempt to do this with the economy.”

I would rephrase that. We cannot say that the economy is unstable, but monetary policy tries to make it stable. That makes no sense. Because there is always a monetary policy of one kind or another. What we should instead say is: whether the economy is stable or unstable depends on the monetary policy being followed.

Now, stop all this engineering/math talk for a minute, and look at my top picture. What do you see? What do you see as the difference between the economy with the red AD curve and the economy with the green AD curve?

Min: “Another word for “departure” is “error”, the difference between prediction and data. Another word is “perturbation”, errors which have causes that are not part of the model. It sounds like old economists paid more attention to concepts like error and perturbation than new economists.”

No. That is missing the point.

Look at the top diagram. There are two sorts of errors we can make:

1. We can make errors in understanding the things that shift the AD and AS curves, so they shift when we don’t expect them to, or don’t understand why they shift. Old and new economists are exactly the same with those sorts of errors. We know we will make them. That’s why we put an error term in all our equations.

2. We can make an error in saying that the economy is always at the intersection of the AD and AS curves.

The second sort of error has very different effects, depending on whether we have the green or red AD curve.

Moi: “Another word for “departure” is “error”, the difference between prediction and data. Another word is “perturbation”, errors which have causes that are not part of the model. It sounds like old economists paid more attention to concepts like error and perturbation than new economists.”

Nick Rowe: “No. That is missing the point.”

What I had in mind was this, from the text:

Nick Rowe: “And that’s central to the critique of the old view. If your model says that X* will happen, how can you talk about what would happen if X were different from X? According to your model, X can’t be different from X. You are contradicting your own model.”

To say that X can’t be different from X* is to ignore errors. And that makes it a bullshit critique. 🙂

Nick Rowe: “What do you see as the difference between the economy with the red AD curve and the economy with the green AD curve?”

An economy with the green AD curve is one where deviations are dampened by negative feedback. An economy with the red AD curve is one which is inherently unstable, because deviations are magnified by runaway feedback. And deviations always occur.

Min: OK, you get it. You just talk funny. Probably engineer-speak!

Just because I have defended the “old” idea of stability does not mean that I deny the new one. In fact, my example of the solar system is one of new instability. We assume that we can predict the motions of the planets accurately far into the future, and that our model is correct. Then we find instability that is not the result of deviation from the model. BTW, in the case of the solar system, chaotic is a better term than unstable.

Nick Rowe: “Min: OK, you get it. You just talk funny. Probably engineer-speak!”

I do talk funny, now that you mention it. 😉

Systems speak, I would say. 🙂 Actually, I am more a student of human systems than other kinds.