These notes on the HST and how it compares to the old retail sales tax were prepared by Frances Woolley.

There are two fundamental differences between the new Harmonized Sales Tax (HST) and the old provincial sales tax or Retail Sales Tax (RST or PST).

The first difference between the taxes is the tax base. The harmonized sales tax applies to both goods (hockey sticks and hairdryers) and services (hot waxes and hairdressers). The retail sales tax applied, for the most part, only to goods (cars and computers).

The second difference between the two taxes is that the HST gives firms input tax credits for any taxes that they paid on inputs to production. With the current provincial sales tax, if a furniture manufacturer buys $100 worth of transportation services or equipment or telecommunications, it pays 8 percent provincial sales tax or $8. Then, when the manufacturer goes to sell the furniture (say for $200), the furniture itself is taxed at 8% for another $16 in tax. There’s more than the straight 8 percent (or 7% in BC) provincial sales tax in goods like furniture – hidden in the price are any taxes paid earlier on inputs. In our example, the total tax is $8 on inputs+$16 on the final product, for a total of $24, for an effective tax rate of $24/$200 or 12%. The switch from RST and HST is expected to lower the tax rate on most manufactured goods.

Basic micro-economic analysis suggests that a tax on two goods at a lower rate is better than a tax on one good at a higher rate. To see why that’s the case, let’s look at two industries, the hairdressing industry and the furniture industry.

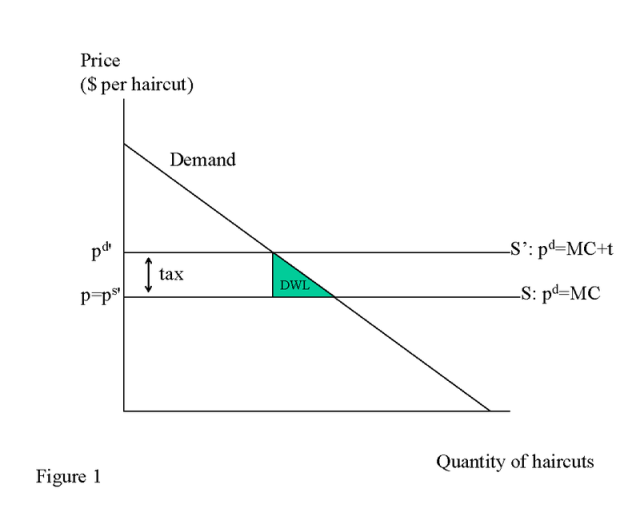

The haircut industry is close to being a competitive industry. There are no barriers to entry into the haircutting business, no economies of scale in hairdressing operations, and so on. It’s not perfectly competitive though. Haircuts are not homogeneous and it’s hard to tell the quality of a hairdresser beforehand. If you believe that a hairdresser has monopoly power over his or her clients then you might not want to believe this analysis. Figure 1 shows what happens when taxes are imposed on a constant returns to scale, constant costs competitive industry. Firms are all producing at a price that just covers their marginal costs. If a tax is imposed, the full amount of the tax will be passed onto the consumer. Prices will increase from p to pd’ and there will be a deadweight loss – some people who might have bought haircuts before won’t buy haircuts now because of the tax, and they will be worse off as a result (note: strictly speaking, to show the DWL as this triangle, the demand curve shown has to be the compensated demand curve).

So if taxing hairdressing creates a deadweight loss, why would we want to tax haircuts? The answer is: we want to have good things like health care and education and roads and pensions for old folks and benefits for children. If we want those good things, we have to raise the taxes somehow. And it’s (generally speaking) better to have two taxes at a medium rate and one tax at a high rate. To see why, let’s look at what happens to the furniture industry when the HST replaces the RST.

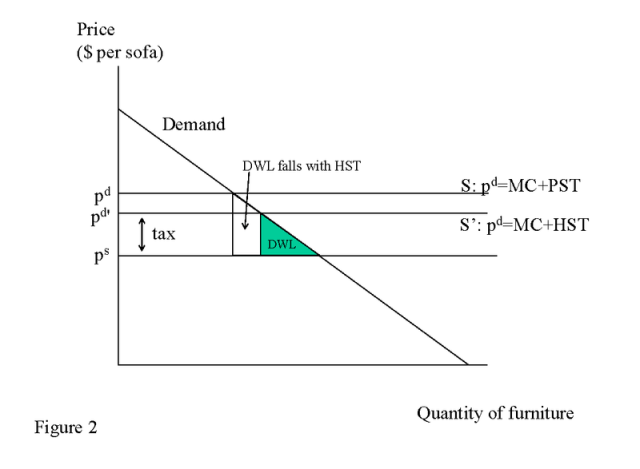

The furniture industry, like the hairdressing industry, is pretty close to being a competitive industry. Anyone can set up a furniture-making business in their basement or garage. Yes, companies like IKEA enjoy some economies of scale, but the industry as a whole is not far off being competitive. Figure 2 shows what happens to the furniture industry when the RST is replaced with the HST. Because furniture manufacturers can now claim inputs tax credits on things like the fabric used to cover sofas, their costs go down. If the industry is competitive, the cost savings will be passed onto the consumer in the form of lower prices – prices fall from pd to pd’. The deadweight loss or excess burden of the tax falls, and efficiency increases.

Notice something really important about that diagram: even though the DWL falls quite a lot, the government doesn’t lose that much revenue – even though it raises less revenue per sofa, more sofas are being sold. This is an application of a basic principle: the deadweight loss depends upon the square of the tax rate. There are relatively high efficiency gains from cutting a high tax.

There’s another way of showing these basic ideas. If only goods are taxed, people’s choices are distorted by the tax, and they will substitute services for goods, for example, going out to restaurants more often rather than buying a new food processor to make meals quickly and easily at home. However if both goods and services are taxed equally, people’s consumption choices aren’t distorted – there is no substitution effect. This means that people can achieve a higher level of utility – get on a higher indifference curve – while the government can raise the same amount of tax revenue. Figure 3 shows these ideas graphically. Here, tax revenue is measured as the vertical distance between the pre-tax and post-tax budget line at the consumer’s optimal choice – that’s the quantity of consumption the government is taking away when it imposes a tax. As you can see, the tax revenue raised is the same at point a, where only goods are taxed (the RTS) and point a’, where both goods and services are taxed (the HST). But consumers are better off, because they’re on a higher indifference curve!

The diagram above assumes all taxes are paid by consumers, and the marginal cost of production is constant – taxes are not somehow absorbed somewhere else or by someone else in the economy. For a lot of service industries like hairdressing, that’s probably a good assumption. For other industries, that may not be true.

One controversial aspect of the HST is that it will apply to new homes costing more than some threshold amount – an amount initially set at $400,000. Part of the cost of building a new home is labour and materials. For these things, the analysis is much like the analysis for furniture and hairdressing above. But those labour and materials costs are typically less than $400,000, except for an extremely large and fancy home. Typically, what makes a really expensive new home so costly is the price of land. New condos in Vancouver sell for a million dollars because of the cost of Vancouver real estate, not because they cost a million dollars to build. But the supply of land is relatively fixed. So the supply of new homes in downtown Vancouver or downtown Toronto will be relatively inelastic, because the supply of downtown real estate is relatively inelastic.

Figure 4 shows the effect of the HST on the real estate market. According to this analysis, the effect of HST would be expected to be reflected in the price of land, and absorbed by the owners of undeveloped real estate. I’ve exaggerated the size of the tax here to make the diagram easier to draw – the basic point is that the bulk of the HST could potentially fall on the owners of undeveloped real estate, not new homebuyers.

This raises a general point about the equity of the HST. A number of people have criticized the HST on the grounds that it is inequitable. There are three possible responses to this claim. The first is official response that can be found on the Government of Ontario website: there will be new refundable sales tax credits that will offset the cost of HST for low income individuals. The second response is based on the argument above: you have to look at supply and demand to figure out who actually ends up worse off or better off as a result of a tax change. It could be that some of the taxes are absorbed, as in the example above, by wealthy property holders or other high income individuals. A third response starts by looking at who buys what: who consumes more services? A lot of the goods that will now be taxed under the HST – airline tickets, pro-hockey tickets, some kinds of investment services – are consumed disproportionately by higher income people. Taxing services can make the tax system more progressive.

The one argument about the equity of the HST is that is harder to analyze is the claim that businesses will not pass on savings to consumers, just like they did not pass on the savings when the GST replaced the old manufacturers sales tax. All of the analysis above assumes that markets are competitive. If markets are not competitive, the savings from the HST may be retained by companies in the form of higher profits, which may be regressive in as much as the companies are owned or controlled by high income individuals.

Indeed, there is a bit of inconsistency in much of the discussion around the HST. On the one hand, supporters of the HST claim that it will reduce the effective tax rate on investment because businesses will pay less tax. On the other hand, supporters of the HST also claim that the cost savings from the HST will be passed onto consumers. You can’t have it both ways – if businesses are going to get a higher rate of return on investment, it has to be because they aren’t passing on the full cost savings from switching the HST on to consumers.

One final thing that I want to talk about is tax evasion. A number of commentators have argued that the HST will increase the amount of tax evasion. In theory, this argument has merit. A rational tax evader will evade up to the point where the marginal benefits of evasion are equal to the marginal costs of evasion. More taxes increase the marginal benefits of evasion, as shown in Figure 5 below, hence would be expected to increase the amount of underreporting of income in equilibrium from Q to Q’.

There are a variety of responses that could be made to the argument that the HST will increase tax evasion. The first argument is that the input tax credits in the HST system provide an automatic enforcement mechanism – a paper trail that can be followed to find evaders. A second argument is that the HST shouldn’t matter much. Consider, for example, a carpenter. The HST is a tax on his or her labour services. Should he or she evade the HST? If you’re evading HST by offering services for cash, you’re probably also evading GST (5%), personal income taxes+ Canada Pension Plan contributions on self-employment earnings (40%+) and also possibly claiming more child tax benefit or other benefits than you’re really entitled to. If the total effective marginal tax on our carpenter’s labour is currently 50% or more, it probably makes sense for that person to want to evade now anyways.

However perhaps because the HST is on a customer’s invoice, consumers are willing to participate on evasion of HST, and they are less willing to participate in our carpenter’s evasion of income tax and other tax liabilities.

If you'd like a copy of the powerpoint file upon which these notes are based, send her an e-mail.

The original title that I suggested for this was “mindnumbingly boring post.” I thought these might be of use to any of you out there who teach or do tax policy.

I claim the traditional editor’s privilege to provide titles.

Of course, I’m not very good at it…

Why would the incentive to evade the HST be any different from the incentive to evade the RST is replaced? In fact, if you assumed that the deadweight loss triangle from tax evasion is similar to the deadweight triangle from tax avoidance, couldn’t you argue that spreading the tax over services as well as goods might reduce total evasion? (I’m not sure if my theory is correct here in drawing that analogy between evasion and avoidance loss triangles. )

Passing the savings on to consumers I think you could consider to be an empirical question. There have been a couple of studies in CPP that look at this in the context of the Atlantic province early adopters of the HST. Any comment on those?

There was no RST on things getting a carpenter to come and build a new porch, hence the lack of incentive to evade RST on home renovations! I think the argument is the old RST applied to things like purchases of computers or cars where evasion is more difficulty because these are well documented transactions e.g. if you buy a car you have to get a whole bunch of paperwork.

This argument is also being put forward by representatives of the constructions industry.

Jim, you’re right, there’s a good article in Canadian Public Policy in 2000 that looks at the price changes in Atlantic Canada when the HST was introduced. I was really pleased to see that their findings were consistent with my hypotheticals above – household operations and furniture was one of the CPI categories that decreased most in price, whereas personal care (haircuts) went up. What I don’t know is how much “hidden tax” was removed with the switch to the HST in Atlantic Canada, so have no idea what percentage of the tax savings were passed onto consumers.

Interestingly, that CPP article is quite negative on the equity impacts of the HST, because of the increase in taxes on a lot of basic necessities.

“Interestingly, that CPP article is quite negative on the equity impacts of the HST, because of the increase in taxes on a lot of basic necessities. ”

First stop, HST, second stop PGVST (Pigovian Sales Tax) where the government appoints a board of economic experts to adjust the tax weighting of every item to reflect externalities (presumably this would lead to light/no taxation on necessities since they have the positive externalities that come from keeping people alive and avoid the negative positional externalities that plague most other goods), subject to the condition that the total weighted rate of taxation must remain (as much as possible) unchanged.

Interesting post.

My suggestion for a title: Get off the couch, and get ready for a haircut

I hadn’t followed the details of the HST (and I hate those supply and demand graphs in general – these are nice however with some colour) but I hadn’t thought about the double taxation aspect of RST on manufactured goods. So, that was informative, thx.

I can recall when Mulroney introduced the GST, initially it was rumoured to come in at 9%, but got whittled back to 7 (perhaps for political reasons). Now it’s down to 5, which perhaps makes the HST introduction/increases (NS) more palatable politically, in the short term.

Q: O/T but related, I often hear or see economists argue that consumption taxes are better than income taxes because the reduced income tax leads to more personal saving (and less consumption). I’ve never fully understood this argument. Are there some studies that have demonstrated this to be the case? Perhaps a separate blog posting for someone if the reply can’t be easily answered here.

“the basic point is that the bulk of the HST could potentially fall on the owners of undeveloped real estate, not new homebuyers”

could you expand on this? thx

JVFM – I’ll answer in tax professor mode (you might want to go and read about Lloyd George and Avatars instead). People often confuse the way a tax is implemented and what the tax taxes. There’s two ways of taxing consumption. One is with a tax like the GST/HST that taxes people when they spend money. There’s problems with the GST/HST approach. Because everyone pays the same tax rate when they buy something, it’s not very progressive.

Another way of taxing consumption is to allow people to make unlimited RRSP (registered retirement savings plan) contributions and tax any RRSP withdrawals (or unlimited tax free savings account/Roth IRA contributions). With unlimited RRSP contributions, what you’re taxing is income-savings+dissavings. Since income-savings=consumption,that’s a consumption tax too.

Does it make sense to you that having unlimited RRSP contributions would make people save more? If so, then you understand the argument for consumption taxes.

There’s a huge number of studies on whether or not having things like RRSPs makes a difference to whether or not people save. I’m going to try to hyperlink a short summary by Burbridge, Fretz and Veall in Canadian Public Policy. My sense of the literature is that a large chunk of the Canadian population hardly saves anything at all (except for buying a home or – for the lucky minority – having an employer pension)so most of the action in terms of aggregate savings is in terms of what happens in the housing/mortgage market, government debt/savings, and the savings of the very fortunate minority who own most of the assets.

My own personal view is that doing things like changing default options on employer-sponsored RRSPs (you’re in unless you opt out, rather than the other way around), and taking a hard look at credit card regulation (someone on WCI – Declan? – pointed me to a great study showing how the minimum payments on credit card statements actually decrease the amount that people pay on credit cards on average) would probably make more difference to savings behaviour than most other policy options.

I’ve wondered about whether or not the reduction of the GST to 5% was part of some brilliant and overlooked master scheme to harmonize federal and provincial sales. Any political insiders know?

[edited to fix link – SG]

On the question of tax savings being passed on, there was another CPP article in 2009 that I think looked at this more specifically, on a sector by sector basis.

The article Jim mentions is by Smart and Bird. The findings in terms of the patterns of price changes are similar to the earlier article. It found basically that the tax savings from switching from RTS in industries like furniture were passed onto consumers, but also that added costs, e.g. for shelter, some categories of footwear and clothing, were passed on also. They conclude that the increased prices for low-cost footwear, children’s clothing made the switch from RST to HST somewhat regressive (it increased taxes relative to income more for low income people) – but I don’t think they calculated how much refundable credits counter-acted the higher taxes. You can read it here.

[edited to fix link – SG]

Does it make sense to you that having unlimited RRSP contributions would make people save more? If so, then you understand the argument for consumption taxes.

Thanks for the explanation. This would make sense to me if a significant number of people were maxing out on their limited RRSP limits as it sits. Are they? And if not, couldn’t the same outcome be accomplished through better education/marketing?

So, to see if I have this right, the policy initiative is to get people to put more money into RRSPs, and the way to encourage that is by making more money available after income tax. Raising GST/HST rates compensates for lost gov’t income from lower income tax, and the fact that more money will be socked away into RRSPs. Is that the basic idea?

I may have more questions depending upon any responses. Thx

I’m not sure about the B.C. situation, but here in Ontario, your example with the furniture maker would be wrong. Under PST, the manufacturer would not pay PST on items incorporated in the furniture. He is allowed to give his suppliers a purchase exemption certificate for those. The same is true of equipment used directly in production. There is no double taxation on these items.

Certain things are subject to tax. For example, vehicles, office supplies, and telecommunications. So those inputs are, effectively, double taxed in the way you suggest.

I wrote something on the PST-HST change for the local paper. It’s available at http://www.andwhyisthat.ca/ if you’re interested.

I checked the B.C. situation. It’s much the same. Here is a quote from the B.C. Ministry of Finance Tax Bulletin for manufacturers:

“Materials Incorporated into a Finished Product

You do not pay PST when you purchase goods that will be processed, fabricated, or manufactured into, attached to, or incorporated into other goods for resale or lease. To purchase the above items without paying PST, give the supplier your PST registration number. If you do not have a PST registration number and you qualify, give the supplier a completed Certification of Exemption form (FIN 453).”

One thing that intrigues me about moving to the HST in Ontario is the possibility of benefits in the form of tax savings being passed out of province (hopefully here to PEI). Any thoughts on that?

Jim, I don’t expect there will be much difference. Businesses in general are going to save a bit, but manufacturing is one of the least affected because so many of its inputs are already tax-free.

One area where you might see some benefit is telecommunications. Those companies will get significant savings in Ontario, and I expect some small part of that will get passed on to you someday.

Paul, I’m prettty sure you’re right. The Ontario government website gives an example very similar to the one I give, except with a clothing manufacturer – it shows “hidden taxes” on supplies, office supplies, furniture, forklifts, shelving, signs etc all being incorporated into the price of a suit:

tax cascading example. Although it says “raw materials” are taxed and has a picture of some yarn, reading more closely Jack Mintz’s analysis of the 2009 Ontario budget it seems that most of the tax cascading is coming from transportation and equipment and machinery purchases. Mintz, like you, figures that communications is one of the sectors that will benefit from the changes announced in the 2009 Ontario budget: “the METR on small business investment will decline precipitously from 28.6% in 2009 to 13.3% in 2010, especially in construction (43.8% to 15.5%) and communications (47.8% to 14.9%).” B.t.w., I like your article Paul and agree with most of what you say. The post above is basically the solutions for my ECON 3405 assignment, which was “find a newspaper article about the HST and analyze it.” I wish someone had found your article! The best article of the ones that they did was one by Andrew Coyne in MacLeans.

Jim, if people in PEI buy goods manufactured in Ontario, presumably there would be some tax savings. I don’t know if anyone’s thought about it.

Just Visiting – I wasn’t thinking of anything as complicated as you’re thinking. The GST and HST promote savings because if you don’t spend money you don’t get taxed, so people don’t spend money in order to avoid paying tax. And not spending is the same as saving. The RRSP thing is just an analogy – just like putting money into an RRSP avoids income taxes, keeping your money in your wallet avoids GST/HST. So if RRSPs increase saving, GST/HST should increase saving for the same reason.

Hmmm, I may be back to square one on my understanding then. Assume a revenue neutral tax shift from Income Tax to HST.

Say I make $200, and the marginal tax rate is 25%. So, my take home pay is $150. I spend $100 on goods, pay 15% HST and save $35.

Now, marginal tax rates are reduced to 20%. My take home pay is now $160. I spend $100 on goods, and now pay 25% HST and save $35.

My wallet sees no difference at the end of the week. So, I’m not saving anymore than before. Unless I have some Pavlovian response to HST above 15%, I’ll still salivate and buy the same goods.

How about a Pavolian response to your take home pay increasing?

Sorry, Pavlovian. (I was salivating at the thought)

Which will make me…save more? Well maybe. This is Canada afterall…

Just Visiting: Here is an old-ish post on why the GST is a good idea. The basic point is that the GST does not reduce the rates of return on investment – and higher rates of return generate more savings.

Just visiting – “Say I make $200, and the marginal tax rate is 25%. So, my take home pay is $150. I spend $100 on goods, pay 15% HST and save $35.

Now, marginal tax rates are reduced to 20%. My take home pay is now $160. I spend $100 on goods, and now pay 25% HST and save $35.

My wallet sees no difference at the end of the week. So, I’m not saving anymore than before. Unless I have some Pavlovian response to HST above 15%, I’ll still salivate and buy the same goods.”

We agreed that when you made $200 and the marginal tax rate was 25%, if you could avoid paying taxes on some of those earnings by putting the money into an RRSP you’d do so?

You can avoid paying 25% HST by just not spending money – you don’t even need to go through the hassle of opening up an RRSP. So wouldn’t that option of avoiding some tax by not spending money i.e. by saving more make you think you’d like to increase savings?

Now, as a practical matter, I’m not sure that it does, because most people hardly save anything outside of their mortgage and other forced savings. But that’s the theory.

This is actually a different point from the one Stephen is making in his post.

I was wondering actually if there might be some inducement from the lower income tax rate to work more, or would the knowledge that you’re getting hit another way take that incentive away?

SG: You are arguing in your earlier blog that lowering Corporate tax rates increases investment. OK, I can agree with that. Beyond that, and I’ve read it a number of times, you’ve lost me. The premise is that Canada is lacking in investment at the current tax level. What’s the proof? Can you have too much investment under your model?

Frances – you suggest that high levels of GST/HST encourages savings (discourages purchasing). So, do Nordic countries with high VAT rates save more than us? When cheap Chinese goods became widely available to Canadians through the infiltration of Walmart into Canada, did we save more due to having more net income available when an Eaton’s toaster went from $48 to $12 at Walmart, or did we simply purchase more cheap consumer goods for the same amount of money?

“I’ve wondered about whether or not the reduction of the GST to 5% was part of some brilliant and overlooked master scheme to harmonize federal and provincial sales. Any political insiders know?”

One of the effects of the reduction in the GST (or the federal portion of the HST) is that is a shift in tax room to the provinces. We’ve seen in already with both Quebec and Nova Scotia increasing the QST and the Nova Scotia portion of the HST to eat-up the federal GST cut. And, I suspect that when the current (unsustainable) federal-provincial transfer agreement expires in a few years the federal government (regardless of who is in power) will tell the provinces that, if they want more money, they’re more than free to take the extra 2% of GST revenue that the feds have left on the table, and use it to fund their programs themselves (as they should).

While the obvious motivation for the GST cut was political (the Tories wanted to get elected), given the Tories’ ideological preference for keeping the feds out of the affairs of the Provinces, I have no trouble believing that having the provinces take over this tax room was not unexpected or considered undesirable.

More title suggestions:

The Plate of Beans: How to Overthink It.

Rate my thesis title: Hot or not?

First, my bias:

I see the this change (to HST) as essentially a long overdue reform.

Not perfect it its execution but better than what has preceded it.

One way to look at taxes is social utility. In other words will the result of the tax be to promote more desirable activities and/or less of undesirable ones.

I think when it comes to consumption tax, the first social utility, in the absence of other factors is to say that those who consume resources are the greatest cost to society, and therefore ought to bare a proportionate burden.

In simple terms if you buy $1,000,000 worth of ‘stuff’ (be that homes, land or goods or services) you by nature have caused more cost to government and society than those who have bought $20,000 in worth of ‘stuff’.

Of course, this is perfectly true for a long list of reasons. From how a product was produced, and where, to how long it was transported and by what means, to whether a given professional is performing a pubically desirable service and so on. However, calculating every last element of the preceding is recipe for both a hopelessly complex and by nature arbitrary system of taxation.

Better to address these issues, as appropriate though statue (legislation) rather than taxation.

On the whole, the change in system is beneficial from points-of-view that endorse fairness, simplicity and economic competitiveness.

The one downside, arguably, is the lack of progressivity.

However, it should be noted that rent is exempt as are basic groceries, which constitute together more than 60% of expenses for most low-income families.

This has a very progressive effect, even before factoring in tax credits.

That said, that the tax credits are the one real knock on the new intiative.

As the rate of PST is 8% and GST 5%; one might reasonably expect the new PST tax credit to be 60% richer than the comparable GST Tax Credit.

At least in Ontario, that is not true.

Indeed not only is total credit lower, but its phase-out begins more than $10,000 sooner than that the comparable GST Credit.

If that one fact were addressed, I think there would no reasonable argument against the change.