It's handy – if not entirely accurate – to think of the decision to go to university as being one in which the costs and benefits of post-secondary education are weighed. Since governments control or influence many of the key factors in this decision, this is a convenient framework for policy-makers.

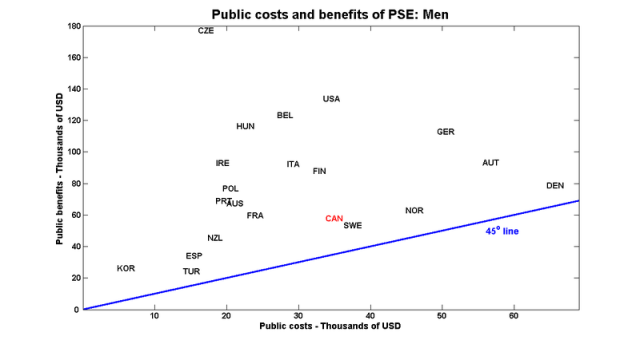

But a similar exercise could also be done by policy-makers. It's generally assumed that the public benefits of PSE justify the costs, but to what extent?

The OECD's 2009 Education at a Glance puts together numbers for 21 OECD countries, and I've summarised some of them in graph form.

Public benefits and costs are defined in a narrow way: increased government revenues are a public benefit, and increased government expenditures are a cost. No attempt is made to identify and estimate the effects of spillovers and/or externalities generated by PSE. Similarly, estimates for private costs and benefits of PSE are strictly monetary.

Private benefits include higher wages and lower risk of unemployment, and private costs consist of the direct costs of PSE, the foregone income, the higher tax bill that comes with the increased salary, as well as the loss of whatever transfers that are directed to low-income households.

Some of those private costs are simply transfers to the government: higher tax revenues are counted as a public benefit, in addition to reduced spending on unemployment benefits and social transfers. Public contributions to PSE and the tax revenues from foregone income are classified as public costs.

All numbers are present value terms using a 5% discount rate and expressed in USD.

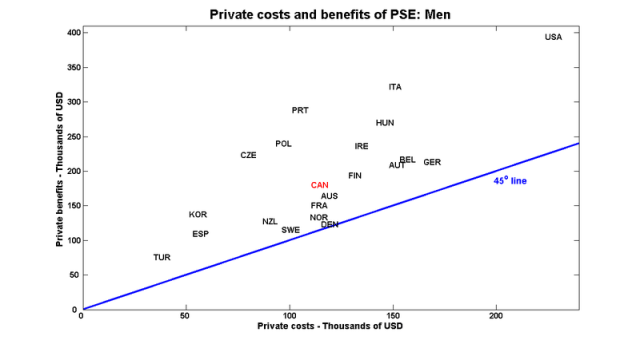

Here are the private costs and benefits for men:

The 45o line traces out combinations in which costs equal benefits. All the data points lie above this line, indicating that for men in these countries, the benefits of PSE are greater than the costs. Interestingly, the Scandinavian countries are clustered close to – but still above – this line.

My alternative title for this post was "Why do French women go to university?". For a number of reasons – a less-than-average PSE wage premium, higher-than-average transfers – the estimated net financial benefits of PSE are negative for French women and are barely positive In Sweden and Denmark.

The public benefits of PSE for men clearly outweigh the costs. In fact, these benefits are probably understated. The OECD's choice of a 5% discount rate may make sense for calculating private NPVs, but governments should use a lower rate. Since the public costs of PSE are front-loaded and the benefits follow, using a lower discount rate would increase estimates for benefits, while leaving costs unchanged.

Governments in Scandinavia somehow manage to lose money when women attend PSE: the increased tax revenues don't cover the costs. OTOH, if governments use a lower discount rate, then this conclusion would likely be reversed.

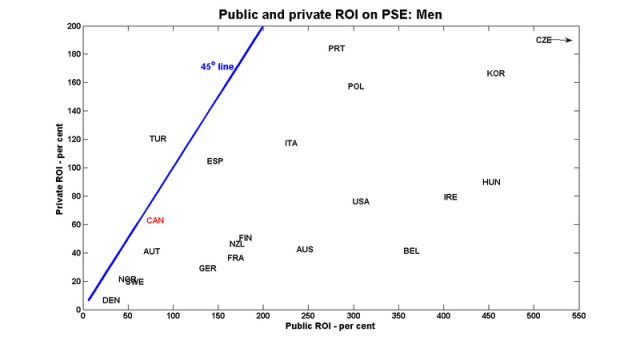

Another way of expressing these numbers is as a return on investment (ROI), where the net benefits are expressed as a percentage of the costs.

With the exception of Turkey, public returns on PSE for men are greater than private returns, usually by a wide margin.

This graph shares most of the same features as the previous one: public rates of return to PSE are typically higher than private returns. The exceptions are Turkey (same as for men) and the Scandinavian countries.

A couple of points:

- Public benefits are associated with increasing participation in PSE. Increasing public spending generates a return only if that persuades more people to pursue higher education. Simply spending more on the same number of students will not generate more revenues later on.

- A tax system with high personal income taxes and generous transfers will always run the risk of reducing the returns to higher education. The Scandinavian countries are closer to this problem than anyone else*, but the fact that they have relatively high PSE participation rates suggests that they've found a good way to structure their incentives.

* I think I read somewhere that one of the reasons why Sweden reduced its top personal income tax rate back in the 1990s was its effect on the returns to education. Should have bookmarked the reference…

What, if anything, do these graphs suggest about the direction a gov’t should take in terms of the balance of who pays for PSE?

For example, if I was to look at the last graph, and compared women in France (Pub ROI 180%, Pri ROI 0%) with women in Canada (Pub ROI 50%, Pri ROI 50%), could I conclude that the French gov’t could pick up a larger portion of the total costs (reducing private portion of tuitions etc) – shifting the FRA data point to the left and up towards CAN?

That’s the sort of conclusion I would draw. Although the key point to remember is that you don’t get the public ROI if all you’re doing is giving money to people who were going to go to university anyway. That increased spending has to be on persuading people to take up PSE.

Great charts Stephen! And good point in the comments about the need for increase spending to be on people who wouldn’t otherwise take up PSE.

Although I know you’re going to disagree vociferously, shouldn’t tuitions be kept low as a method to encourage people to attend PSE?

Fascinating topic, intriguing data.

Are individual incomes or household incomes used to determine private benefits to education? I ask because, private benefits to women may come through household income not personal income.

Along similar lines, I would suggest that the home production contribution of post-secondary educated (PSE) women is higher than the home production contribution of PSE men. In this exercise, those benefits are not measured, not to suggest that they would they easy to estimate.

I would also point that in many northern European countries, high productivity levels are consumed as leisure, e.g., long periods of vacation. In theory, some of this increased leisure time is used in a manner that reduces demands on the welfare state, e.g., better health through increased physical exercise.

If northern European are like North Americans, PSE workers there are exhibiting lower rates of obesity and tobacco smoking which should translate into higher economic output and less demand of welfare state services.

Of course, all this assumes that PSE doesn’t just serve as an (expensive) signalling mechanism.

Bob Smith: Would you regard tobacco smoking and obesity as expensive signalling mechanisms?

Well, smoking and obesity are expensive (what’s a pack of smokes going for these days?), but they’re not signalling mechanisms in that they don’t simply signal that a person has an underlying attribute (poor health) they actually cause that underlying attribute. I suppose that they could be used as a signalling mechanism in other contexts. For example, if smoking is correlated with not-going to university, being a smoker may be an indicator that you’re not university educated. But typically that’s not a really useful signalling mechanism, since you can just as readily (and at far lower cost) just pull out your university degree or your old Queen’s T-shirt to signal that you’re a university grad.

On the other hand I’ll bet you’ve heard someone say “I’m going to university so that I can get a good job when I graduate”. The question is, does PSE actually make people better workers (helping them get a good job) or does it just serve to help identify the people who already have the traits to make them better workers (smart, hard working, willing to jump through the requisite hoops to be a good middle manager), therefore helping them get good jobs. Similarly, are people healthier because they go to university or are people who would be healthier anyways more likely to go to university (for example, because they were raised in wealthier/healthier/better-educated families). If you believe that going to university makes people better workers or healthier people, than money spend on PSE may be socially beneficial as it produces higher incomes by producing better workers (or healthier people). If you believe that people who go to university are the people who would be better workers or healthier people anyways, money spent on PSE is privately beneficial (as it helps the good workers distinguish themselves from “bad” workers and the healthy people distinguish themselves from the unhealthy people), but it is socially wasteful because it doesn’t actually make them better workers or improve their health.

It’s an important distinction, because unless you can disaggregate the extent to which post-secondary education causes higher incomes or greater health and the extent to which it is merely corelated with those outcomes (as a result of unknown hidden variables like intelligence, work-effort, etc) you’re probably going to overstate the social benefits of spending on post secondary education. My own suspicion is that, to a large degree (though not entirely), the social benefits of PSE are illusory, as they merely reflect the fact that people who go to university or colelge are likely to be more productive workers or healthy people than people who don’t go to university. I’m certain that the OECD study (which makes no effort to control for this fact) badly overstates the social return of post-secondary education.

A couple thoughts:

– I’m assuming the private benefit of university is an observable monetary benefit. In other words, if people enrol in university in part because they like to learn, or perhaps to better themselves in pursuits that do not generate income (e.g. homemaking), your graphs underestimate the private benefit of attending university. This could be why French women attend university. Or perhaps the private cost is not entirely borne by the individual receiving the benefit (e.g. they receive a scholarship or help from Mom and Dad).

– I think it’s a stretch to argue there are public benefits from university attendance. The fact that university grads pay higher taxes is a result of how the tax system is designed (i.e. people who earn higher incomes are taxed more), not really a result of university attendance in and of itself. If we had a head tax system, for example, university attendance wouldn’t seem to have any public benefit at all.

David: “I think it’s a stretch to argue there are public benefits from university attendance. The fact that university grads pay higher taxes is a result of how the tax system is designed (i.e. people who earn higher incomes are taxed more), not really a result of university attendance in and of itself. If we had a head tax system, for example, university attendance wouldn’t seem to have any public benefit at all.”

If you accept that university education makes people better (i.e., higher earning) workers, than there is a public benefit to it GIVEN that we raise revenue through income (and consumption) taxes (in that people who earn more money pay more income and, typically, consumption tax). You’re right, there wouldn’t be that kind of benefit if we had a head tax, but given that we don’t have a head tax, that’s sort of a moot point.

As I noted above, though, there’s no public benefit to PSE if it just identifies people who are better workers (without actually making them better workers), since in that scenario those people would pay more income tax regardless of whether they went to university or not.

Bob Smith,

If I understand you correctly, you’re arguing that if university is just used as a signalling mechanism and doesn’t increase the graduates’ work effort or abilities, then it doesn’t have an effect on productivity. However, surely, if this signialling mechanism didn’t exist, then there would be some losses incurred in the economy by the lack of a good signal of workers’ producitivity. Productive people would have a hard time getting good jobs and unproductive people would too often be placed in high-paying jobs. I can immagine that the costs of constantly hiring and firing would outweigh alternative costs of the university degree.