The comments on the post Neo-classical economics is dead. Sort of. and Why economics textbooks are (sometimes) ideological show there is a fundamental disconnect between what economists do and what the general public thinks we do. There's also a fundamental disconnect on what economists believe and what the general public thinks we believe. And it's mostly our fault. Why?

The Economics Profession and Incentives

If you want to gain tenure as an economics professor, either Publish or Perish. You need to publish articles in the top-tier journals. Everything else is secondary or tertiary. This includes promoting your research to the general public or even having research that is valuable to society at large (if it is, great, but all that matters is that it's published!). As such, spending time helping the public at large better understand economics or the economic profession comes at a real cost to an economist.

Business schools are a bit better in this regard. Mainstream business publications (e.g. Profit Magazine) often publish findings from academic business research. At Ivey, for instance, incoming tenure-track faculty attend media training and there is an expectation that faculty members promote their work to the media. I once asked a senior faculty member if media relations matters with tenure decisions and he stated "At the margins, yes. A superstar is going to get tenure no matter what she does and no amount of media spotlight is going to save a poor candidate. But for the borderline candidate, it is taken into consideration."

Incentives Determine Which Economists Seek Media Spotlight

Being in the media overall at most is a slight benefit to one's career and at worst a major distraction. And there isn't much/any money in it, particularly at lower levels. I've done dozens of radio interviews, from CBC to local radio to NPR in the US. All of the gigs were unpaid though occasionally I would be sent a small perk, such as movie tickets, etc. At higher levels I'm sure there are more benefits, but I can't imagine they're a whole lot. I can't say with a lot of certainty, as the closest I've ever got was an unsolicited (by me) first phone job interview with a TV show on Fox and the discussion never got to money. Or to a second interview, which makes sense because I'd be horrible at the job.

Like everyone else (or perhaps moreso), economists will gravitate towards the media when the benefits outweigh the costs. There is little direct financial benefit, so the benefit has to come from getting a soapbox to promote something else. It could be a book, but often what is being promoted is a political candidate or party that the economist believes in.

This skews the view of the profession to the general public, as the economists they typically see have an ideological or partisan axe to grind and aren't fully representative of the thoughts of the profession as a whole.

Incentives of the Media

Like anyone else, the media too have their incentives – and the incentive is to provide a show that is interesting to their viewers and listeners. The difficulty is that most mainstream economists have to give boring answers.

I used to be a semi-regular guest on one radio call-in-show with my topic of choice being exchange rates. On my seventh or eighth appearance on the show, the host made a remark along the lines of "High oil prices: Good for Canada. Agree or Disagree?" My answer, "well, it depends…" and talked about some of the things it depended on. I like to joke with my students that the answer to any economic question is 'well, it depends' and our role as economists is to figure out what it depends on.

As soon as the interview was over, I knew they were never going to call me back. That's not what they wanted – they wanted someone to either excitedly agree with the host OR someone who would argue strongly against. That's entertaining radio. But a sensible, level-headed analysis of the costs and benefits? BORING. They never did ask me to appear on the show again. I don't blame them – if I was in their position, I'd look for someone else.

The economists who stay on the air tend to be the ones who are most willing to promote a black/white worldview. That tends to skew the view of the general public, as most economists tend to see everything in shades of grey. But shades of grey makes for bad TV.

Humans, individually and collectively, are not by nature selfish pigs, I believe. They are by culture, reinforced by societal economics, theoretically and practically.

Compare the infant mortality rates between Cuba and Jamaica.

Lesson of the thread:

Economists are really, really, appallingly bad at history and politics. Frances gets a pass for being the lone voice of reason.

Blikktheterrible – I don’t think communism v. capitalism is a particularly useful way of thinking about the world. I don’t even know what a capitalist society looks like. Sweden? India? Haiti?

Is China communist or capitalist? Well, it’s governed by the communist party, some markets and some aspects of people’s lives are very tightly controlled, so that makes it communist. But some markets are unregulated and competitive, which tends to make it capitalist.

And which is better depends on who you are. If I had to live in the bottom 2% of the income distribution, I would pick the USSR over the US.

Lest you think this is grossly naive – yes, I did travel in Eastern Europe while it was still communist. I remember trying to explain to people what unemployment was (this was the ’80s). They just didn’t get the concept. They really didn’t believe us when we tried to explain yes, you can be smart and educated and hard working, and still not be able to find a job.

Frances, I believe I was in kindergarten when the Soviet Union collapsed, so I had no opportunity to see what it was like in the Soviet sphere of influence. I feel pretty confident that no textbook I ever had in US public schools expressed any of what you just said about communism. The implicit message always seemed to be that communism was worse for every segment of the population. By communism, I mean the system in the Soviet sphere as well as China under Mao.

I want to clarify that my question wasn’t intended as any sort of anti-communist dig on you. I’ve just never heard a Western economist make these sort of statements, so I wanted to be clear about what you were saying. I personally favor economic policies that are best for the poorest of the poor, but I had always gotten the impression that complete state control failed to do that (especially in the long run), hence the failure of the Great Leap Forward. I’m not saying that you have single-handedly changed my view, but your commentary is totally different from that of anyone I have ever considered worth listening to.

“Humans, individually and collectively, are not by nature selfish pigs, I believe. They are by culture, reinforced by societal economics, theoretically and practically.”

I don’t think any mainstream economic theory of the last 100 years has relied on the assumption that humans are “selfish pigs”. I don’t think that’s an issue that economists concern themselves with professionally. I could be wrong.

Tom Slee

On markets: Google OECD Household production. Or see eg Butlin on the Australian economy, or the Australian Bureau of Statistics (and similar bodies in other countries) studies of the size of the household sector. All these put household production of goods and services at equivalent to around 30-40% of GDP. Figure in that government is, in most developed countries, 25-30%. Factor in off-market transactions inside firms, and add the not-for-profit sector. Then make some allowance for the market activities of government and households. Apparently we do not, even in “market economies” trust the market to actually produce and deliver most goods and services.

The comment that “government are coerced markets” cracked me up. It took a lot of expensive mis-education to produce that one.

I thought Nick’s reply to my comment was thoughtful and honest. It basically said “economics has an incomplete understanding of a part of the relevant phenomena”.

My ask is that some equivalent words accompany all policy advice. As one of the bunnies embarked on the ship, I prefer the officers to appreciate that they are using dead reckoning in poorly-charted waters.

Part of the problem of economists bad standing in the world is that some of the representation of what they think and do is made by the Gordon Gekko’s of the world. The willingness of economists to separate themselves from that representation is in question.

“I don’t think any mainstream economic theory of the last 100 years has relied on the assumption that humans are “selfish pigs”. I don’t think that’s an issue that economists concern themselves with professionally. I could be wrong.”

Pigs appear by nature selfish with little or no consideration for others. Humans are not. With humanity ego (regard for self-interest) and empathy (regard for others-interest) evolve together in children. They learn selfishness (lacking consideration for others; only concerned with one’s own personal profit or pleasure).

Yes, professional economists haven’t been concerned with selfishness, but they’ve been inadvertently culturing it. And more broadly, no materialistic philosophy, communist or capitalist, has thought about it – though, in my view they are collectively unconscious slaves to its passion: perhaps from observing Commie’s and Cappie’s piglets competing for the best nipples on mum.

Economists don’t need to rely on selfishness though I think they believe they do. Perhaps without it they believe the whole damn theoretical system will fall apart. Not so: I think competing self-interest with personal sovereignty, specialization, free and fair markets are needed to create a valid economics.

I have to say that I haven’t had the same issues with economics that most of the other posters have had. My academic experience has consisted of just two introductory econ classes.

I don’t remember having any problems with the assumptions made in introductory micro, except maybe continuity of supply and demand curves, but I was willing to assume that the differences would aggregate out. None of the “philosophical” assumptions bothered me at all.

I did have some major issues with introductory macro. There were two big ones and they both had to with the relationship between money and the real economy. The first was the assumption that the velocity of money is independent of changes in price, money supply, and GDP. We were given essentially no evidence that that was the case, which left me feeling like there was no reason to believe in the Quantity Theory of Money. The second issue was why an increase in the money supply should cause an increase in aggregate demand. In both cases, I would’ve been mollified if the professor had just said that studies had shown those results to be true, but she didn’t and I saw no a priori reason to think that either was true. That was where introductory econ fell flat on its face for me.

I’m MUCH more concerned with whether a model’s predictions match reality than whether its assumptions do. The former is a matter of intellectual concern, while the latter is a matter of practical concern, at least if the model has predictive power.

I’ve never taken any economics; the closest I’ve come is reading about early theories of political economy or books by Joseph Heath. I agree that the field isn’t terribly well represented in the popular (or any) media, though it’s fair to say that journalists – who generally have little to no specialized knowledge – often do an appallingly poor job of representing any field. My own background is in political science, math, and stats, all of which have given way to medicine (2 years to go…) on a more or less permanent basis.

The census issue aside, the media never talks to mathematicians or statisticians, and they tend to interview and solicit commentary from the relatively rare but loud partisan political scientists (e.g. Tom Flanagan) over the vast majority of apolitical academics. I remember once during a seminar class in undergrad my prof made a remark about economics as being associated with more “right-wing” viewpoints (contrasted with sociology, etc.). I disagreed that that was actually the case, but he was of course talking about the perception. My view is that there are simply far too many people with “libertarian” or similar viewpoints who don’t actually know anything about economics (except possibly at the level of an intro course), yet feel little reluctance to cite the field to justify their ideology. They aren’t interested in models or caveats or data but in supporting a political project (the worst ones usually talk a lot about “Austrian” economics and seem to metastasize around cyberspace).

Anyway, my personal impression is that economics as a field has become too technical and divorced from the sorts of political and social questions that were on the mind of early political economists. It’s a lay view, but it could be applied to other fields in social science as well. As for models, as George Box said, they’re all false, but some are useful. And models with fewer assumptions are to be preferred where feasible.

“We dont assume people are inherantly self-interested, simply that they are self-interested when engaging in market transactions and if we are limiting ourselves to the study of these transactions we can safely make the assumption that people are self-interested.”

Not just market transactions: also in how the economic system framed by the organization of the collective firm, which is “selfishly” bent on maximizing profits and minimizing costs. To me collective firms and collective farms represent the “fat pigs” of capitalism and communism. Both are a product of social engineering.

Are people just self-interested/selfish when engaging in market transactions? Think not. Empathy is involved and it is easily see in the flexible price (barter) and personal service public markets in Asia.

As an action researcher I set up a small trial, where there is uncertainty as to quality: my market for melons with flexible prices and personal service. Here’s what I did. Honeydew melons when ripe are not so good looking with varicose-like veins and skin a touch tacky. The vendor knows this but doesn’t know I know since I smile sweetly and ask her to pick for me. Invariably, they pick the best one. Why? The hypothesis is that they empathize with me. They don’t selfishly supply something inferior if they can get away with it and save the better to make a sale later – which is what I see happening with Akerloff’s market for lemons based on fixed prices and selfish service.

Another indication that not only self-interest but empathy is involved in the marketplace is seen with barter – and is just common sense. To barter well and be a good salesperson you need to read your customers to find a price where you both win as well find the qualities that suits the consumer. That “read” is empathy.

Another example of empathy and altruism in the marketplace is with my wife, who is a fashion designer and clothes maker. She has four price levels: a regular price, a higher one for police uniforms (she literally charges them for being corrupt) and highest price for the rich (who have way too much). For the poor and female monks she altruistically works for free. She says: “Every poor person needs good clothes to go to the temple on monk day.”

Blikk: “I did have some major issues with introductory macro. There were two big ones and they both had to with the relationship between money and the real economy. The first was the assumption that the velocity of money is independent of changes in price, money supply, and GDP. We were given essentially no evidence that that was the case, which left me feeling like there was no reason to believe in the Quantity Theory of Money. The second issue was why an increase in the money supply should cause an increase in aggregate demand. In both cases, I would’ve been mollified if the professor had just said that studies had shown those results to be true, but she didn’t and I saw no a priori reason to think that either was true. That was where introductory econ fell flat on its face for me.”

That’s interesting (to me, as a macroeconomist, and teacher of intro).

In defence of your prof, and speaking as an economist who has spent a lot of time thinking about and trying to explain those points, I just want to say: it’s hard (not all economists understand it, and none of us understand it all really fully); and it’s harder still to explain. The transmission mechanism from money to AD is one of the things I have been arguing about, for example, with people like Adam P, who knows a lot of macro.

By the way, there is no a priori reason to think that V will be independent of real GDP. In general it won’t be. But it works reasonably well as a very rough empirical approximation (the income elasticity of the demand for money is somewhere near one, just don’t interpret “near” in the way a physicist or engineer would interpret “near” 😉 ). The higher your income, the more money you want to hold, other things equal. Suppose it’s roughly proportional.

Blikk, I more or less second what Nick said.

However, I would point out that in the typical undergraduate level model the assumption that velocity is constant implies that an increase in the money supply should cause an increase in aggregate demand. These are not two issues, this is one issue.

To me the constant velocity model is just a simple example that helps one see how an increase in the money supply might increase AD. After all, if M increases and V stays the same then P and/or Y must increase and if you think through the mechanism of what makes P and Y increase it, in the simple model, must be that AD increased.

Now, my “in the simple model” statement hides a lot. Basically it imposes a decentralized market structure and a certain restriction on the information that agents in the economy have. The idea here is that the increase in the money supply is not known to everyone (or its implication not understood) which rules out everyone realizing together that “well the money supply doubled so I should double my price”. Thus, the “in the simple model” statement rules out that sort of co-ordinated price response.

This is important because a lot of people do believe that in real life people will respond like that (which they should if they know that the money supply doubled) and thus that money will not change ouput, only prices. However, in the absence of such a coordinated response it follows that P and/or Y only rise if higher AD drives them up. (I suspect Nick might disagree a bit with this explanation but that’s my understanding of the undergad type macro model).

The important point though, (and here I’m certain Nick would agree) is that we’ve now made actually a large amount of progress. Arguing through the constant V example has led us to conclude that how monetary policy effects the real economy depends crucially on the details of agent’s information and how they themselves understand the macro economy. This is a conclusion that is pervasive and survives a generalization beyond the assumption of constant V (even to models of economies with no money in them). Of course it also points up why your teacher couldn’t give you a simple “studies have shown…” qualifier, since these sorts of expectations on the part of agents is hard to observe different studies have shown different things.

Carrying on though, I personally happen to think that the quantity theory of money is completely useless. I think that any real effects of monetary policy have to work through the real interest rate/asset prices and that the quantity theory is a poor, poor context for understanding this. (But that’s something I know Nick disagrees with).

“If I had to live in the bottom 2% of the income distribution, I would pick the USSR over the US.”

How can you really choice either way?

If the year is 1955 and you lived in the US, you’d be a poor black man from the South during the Jim Crow era, worried that if you made eye contact with the Sheriff’s (white) daughter, you’d either be jailed or lynched.

If you lived in the USSR in 1995, you’d be Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.

The question reminds me of one of those “Would you rather?” drinking discussions: “Would you rather be hit in the face with a 2×4 by Jose Canseco or lose several toes in an industrial accident?”

Both options are so positively awful, I’m not sure how you pick.

err, USSR in 1955.

How can you really choose. I knew not going to Starbucks this morning was a bad idea.

Solzhenitsyn wasn’t in the bottom 2% of the income distribution. He was in the bottom 2% of people willing to get along with the government.

Part of the point that I took from the statement was that even if both sides had people in horrible situations, they were not the same class of people in both places, so for some people it would make sense to switch.

“Both options are so positively awful, I’m not sure how you pick.”

I think that’s a good point in the sense that we do generally have a poor sense of how to feel about very abstract hypotheticals, but I think the question itself is of a variety deeply fundamental to economics and one that many people deal with fallaciously. Economics is about choice. It’s about choosing the option that is best relative to whatever else is available. Arguments about whether any of the options are good are (in my eyes) fundamentally non-economic. More than that, I think those arguments can lead us to choose bad policies.

This is something that comes up frequently in employment and trade regulations. Most controversially, it appears in most arguments about whether prostitution should be legal. We may observe that women find themselves choosing between working as prostitutes or having themselves or their children starve. The most common response is that no one should have to make that choice because those options are both terrible. That doesn’t solve anything, though. The only way to keep people from (rationally) choosing either of those options is to make a third better/good option available, but that’s not usually what people suggest. People usually try to make the choice illegal, as if that would solve the problem.

Choices between evils are a fundamental part of life for many, if not all people. Economics needs to take that into account. Nothing is more important.

“However, I would point out that in the typical undergraduate level model the assumption that velocity is constant implies that an increase in the money supply should cause an increase in aggregate demand. These are not two issues, this is one issue.”

The two issues are short-run and long-run behavior.

I just remembered a third issue that bothered me in macro: the fictional nature of “price level”. Mike Moffat has written about that. Until I saw his posts about it, I felt like I was the only one who was bothered.

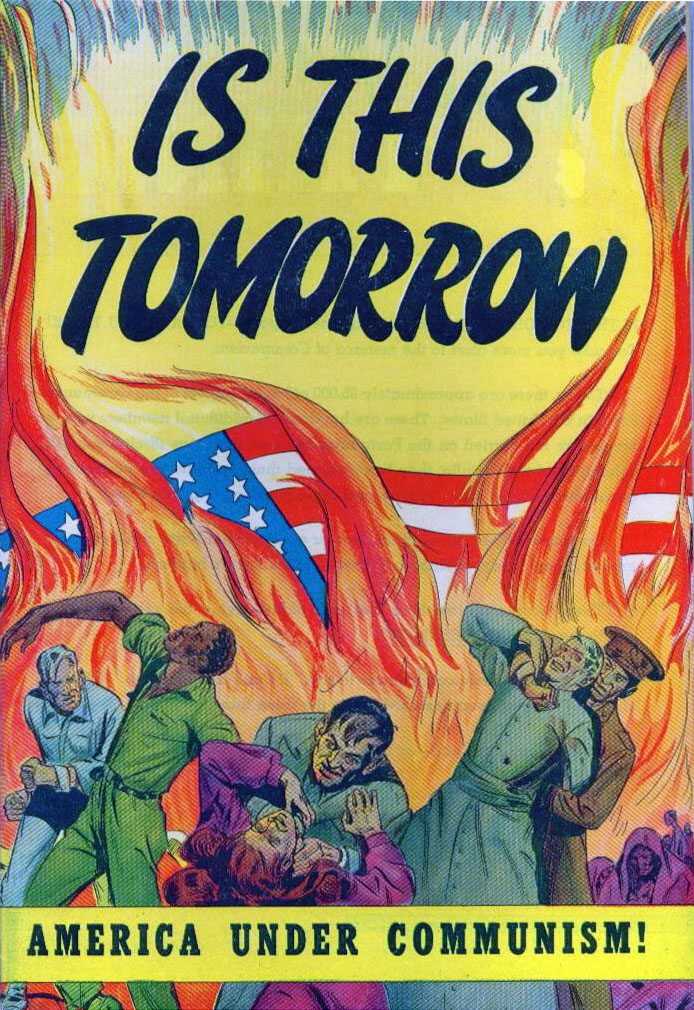

I tried to find a trustworthy source that would show either Frances or Nick to be correct regarding the effects of communism. This is the result:

Given the lack of punctuation, I’m not entirely sure what they’re saying.