I did a round of interviews for CBC radio on Tuesday after the federal government's fiscal update was released, and it was often remarked that the 2009-10 deficit of $55.6b was the largest ever. I suppose I should have said that it sounds even larger if you say it was 5.56 trillion cents.

These numbers aren't really informative without context, so here's some. The data are taken from the Department of Finance's Fiscal Reference Tables, also updated on Tuesday:

First up is the federal budget balance, scaled as a share of GDP and in terms of per capita 2010 dollars:

The 2009-10 number is bad, but we've seen worse. Indeed, we had a string of 18 years in a row starting in 1977 where the deficit was a larger share of GDP than it was last year.

Here is the federal debt:

That upward tick will be something to watch in the next couple of years. A temporary blip is nothing to worry about. A sustained trend is.

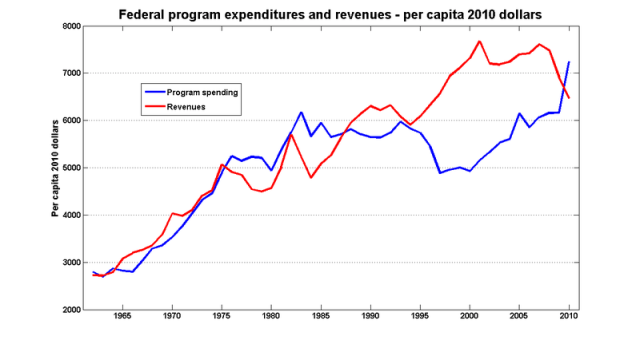

I've found it instructive to look at spending and revenues using both methods of scaling the data.

After almost 30 years of drifting sideways, real per-capita spending jumped sharply. The stimulus program is set to expire in 2011, so the spending should stay in that region before falling back again (how far?) in 2011-12. Unsurprisingly, revenues fell during the recession, but they've already started coming back.

Here are the same series expressed as a share of GDP:

Once again, we see that jump in spending, but only back up to levels we saw twenty years ago.

I have to say that I can't get too excited by the swings at the end of those graphs, even if they do persist through the current fiscal year. On both the revenue and spending sides, the shifts are temporary and will recede during FY 2011-12. There's a better-than-even chance that the deficit will not go entirely away on its own and that further measures will need to be taken, but these decisions don't have to be made right away.

“I’d probably get a 2 in your course that you teach part time. Case studies, that often use real data and external info to complement theory, never have a definitive right or wrong answer – despite what some instructors like to claim. Kinda like Canada’s economy in 2010.”

I suppose that’s fair and I’d never make any claim about economics with absolute metaphysical certainty. (I’m familiar enough with Immanuel Kant not to make that mistake).

But at the same time, I don’t think we have to throw up our hands and say ‘since we can’t be absolutely sure about anything, then everything is equal!’ There’s a middle ground here.

Bob Smith: “the suggestion that moving to a zero-rate on corporate income tax would mean shifting taxes from capital to labour is not correct”

Globally, it is exactly correct, except I should have said labour and other tax payers, which is mostly the same thing. Consider a world with 2 jurisdictions, one with a 20% and one with a 21% CIT. This will be equivalent globally, to an effective CIT rate somewhere between the two levels. The incidence of this effective rate is largely on capital, not labour. (This is not a controversial statement about closed economies). If both jurisdictions shift their CIT up by 1%, the burden of that will be almost entirely on capital. It is the tax differential whose principal incidence is on labour, largely because of capital movements. If the higher tax jurisdiction cuts its tax to 20% there will be two effects: 1) the effective global CIT will decrease, increasing the burden on labour everywhere and 2) capital will flow into that jurisdiction, more than reversing the impact on domestic labour. The second effect is the well known effect documented by the “dozens” of studies that Mike Moffatt mentions. What is often not mentioned is that the benefit is entirely paid for by foreign labour (and then some).

When jurisdictions compete on CIT, the effect is a lowering of the effective global rate and a global transfer in burden from capital to other tax payers (principally labour). It is entirely disingenuous to go around pretending (as many of these studies do), that the incidence of CIT is on labour, and that cuts in CIT are somehow progressive, when it is obvious that in a global economy, they are merely predatory on foreign labour. What’s even worse, because of the prisoner’s dilemma nature of the game, the end result of extremely low CIT is not even efficient.

K,

K,

I’m happy to concede that if there was global coordination of tax rates, then yes, the incidence of CIT would be borne (to some degree, though not entirely) by owners of capital. We would, in essence, be one big closed economy.

But, of course, that isn’t the world we live in. Most countries are small open economies, and therefore the incidence of CIT in those countries is largely borne by labour (it’s different for the handful of large open economies like the US – to some degree the incidence of capital tax in those countries is borne by owners of capital around the world, which I suggest is probably why US corporate tax rates are so high). Given that this is the world we live in, reducing the CIT rate in Canada doesn’t shift tax from capital to labour, regardless of what other countries do.

Moreover, it doesn’t follow that an extremely low CIT rate is inefficient or leads to inefficient levels of taxation on capital income. After all, CIT isn’t the only tool at a government’s disposal for taxing capital. It is just one method of doing so, by taxing capital income at the corporate level rather than doing it at the shareholder level. Incidentally, that is precisely what has been happening in Canada. As CIT rates have gone down, the effective income tax rate on dividends (at least dividends from Canadian corporations received by Canadian residents) has gone steadily up as the dividend tax credit has been reduced to reflect the lower CIT rates (there is some net tax loss to the Fisc, however, as non-residents and non-taxables such as RRSPs and pension plans aren’t affected by this change – though non-residents are caught by withholding taxes and much of the income of non-taxables is ultimately taxed down the road, so that’s really a deferral issue).

Indeed, the fact that Canada (and other developed countries) does not impose entity level tax on other business entities (partnerships and, in some circumstances, trusts – though that’s changing as of January 1) belies the claim that having no CIT results in inefficiently low levels of tax on capital.

Just to follow-up on my last post, by imposing higher capital taxes at the shareholder level, Canada doesn’t face the same mobility issue, because the tax is imposed where shareholders live, not where they invest (as is the case with CIT). Of course, in theory shareholders can up and move to lower tax jurisdictions, but most shareholders (like workers) find it harder to move themselves than their investments.

Bob Smith,

You don’t need coordination for the global effective CIT to be borne by capital. It’s not about changes in the CIT. It’s about the effective global rate which, again, is a rate somewhere in between the lowest and highest rates. And the incidence of this rate is almost entirely on the owners of capital. Period. And no, coordination wouldn’t make the world a big closed economy – we already are one.

Imagine that I said in this forum that a seller in a market should just lower his price by 10% since his loss of income would be outweighed by a huge gain in sales volume. Everyone would (rightfully) call me an idiot and point out that unless I had a production advantage, my price cut would simply be matched by other sellers, and we would all lose income. Similarly, if Canada cuts its CIT our global competitors will be forced to match relatively quickly, and when they do so, we will all have lost. I am not saying that we can avoid this process; I am saying that it’s really bad for us.

I never said that it followed from any of this that a low CIT was inefficient. I said that for other reasons 0 CIT is likely to be dominated by a mix of CIT and other taxes. I also said that because we are in a prisoner’s dilemma in which it is rational for individual nations to try to undercut the effective global CIT rate, irrespective of whether the current rate is optimal, then there is no lower bound to this process. Prisoner’s dilemma does not have an efficient equilibrium.

In the end, the gains you are touting for CIT cuts will be temporary until other jurisdictions match the cut, and for the average jurisdiction, will be offset by periods in which it finds itself at the losing end of the CIT differential. And in the end we will end up at a regressive and grossly inefficient global average CIT rate.

Anyways, I’m getting tired of beating this horse, which should have been dead long ago. Maybe someone else can take it up, or someone who is really hearing what I’m saying can explain to me how I’m wrong. Otherwise, I’m over and out.

Whoa, that was an intemperate late night comment. I take back the attitude. Sorry Bob, and everyone else.