Stephen's got standards. So I'm going to steal his graphs from his last post, and write the post he could easily have written.

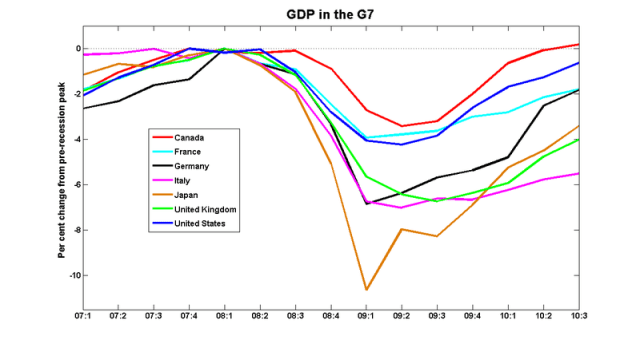

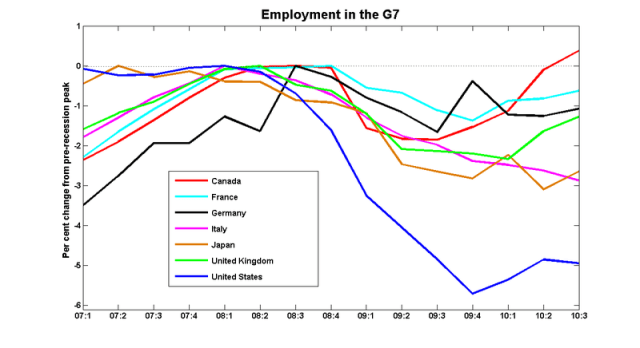

Before you look at Stephen's graphs, ask yourself this question. How well did the US fare in the Great Recession, in terms of GDP and employment, compared to other G7 countries?

Now look at the dark blue lines (that's the US) in both graphs. Compare them to the other lines. Did you see what you expected to see, on both graphs?

OECD data in both graphs.

I could understand if the US had the worst output and employment during the recession. I could fake up some explanation. "The US, with the bursting of its house price bubble, was the epicentre of the financial crisis, blah, blah…".

I could understand if the US had the best output and employment during the recession. I could fake up some other explanation. "The US, with its free market economy and labour mobility, is remarkably resilient to shocks, blah, blah…".

What I can't understand is why the US had the second best output, and yet by far the worst employment. That would require two fake explanations, and it would be hard to make those two explanations consistent.

Each of us thinks our own country is normal. We try to explain why other countries are different. That's especially true if our own country is a large country, like the US. But when you compare the US to all the other G7 countries, you see that it's the US that is abnormal, and in need of explanation.

Ignore the US in Stephen's graphs, and everything looks normal. Some countries did worse than others, and the countries that did worse on GDP tended to do worse on employment. You get roughly the same ranking on either measure. Moreover, the decline in GDP was about two or three times as big as the decline in employment. That's what we would expect, from Okun's Law. It's the US that doesn't fit the pattern. The US is abnormal, and in need of explanation.

Okun's Law tells us that labour productivity, crudely measured as GDP/employment, and ignoring subtleties like hours worked and quality of labour, normally falls in a recession. Because the percentage fall in GDP will be two or three times as big as the percentage fall in employment. And it did fall in all the other countries. But in the US it didn't fall at all. Labour productivity actually increased. GDP fell a little over 4%, peak to trough, and employment fell nearly 6%, so the GDP/employment ratio increased by over 1%.

The US is an even bigger puzzle if you think that business cycles are caused by productivity shocks. Sure, you could always argue that US firms and workers were expecting even bigger productivity growth, so when it actually came in at only 1%, that was a negative shock to productivity. But you would have to work hard to convince me that that's plausible. And what were all the other countries expectations for productivity growth — chopped liver?

Why did US productivity increase during the recession? Why doesn't your explanation also apply to the other 6 countries?

Why is the US an exception?

Surely you are joking ?

This is an easy one.

Because of much less Social Securtity in the US, workers are weak in a recession.

They have two options: work harder or not work at all and have no or very limited unemployment insurance.

Moreover if they find another job they have to accept a lower wage.

The outlier in the opposite direction is Germany thanks to their Kurzarbeit.

See also:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/09/02/kurzarbeit/

ws – so that same output is being produced by fewer workers putting in longer hours for less pay, we should see average hours increasing in the US. We don’t (this is data on average hours worked in the US from the Bureau of Labor Statistics http://data.bls.gov/PDQ/servlet/SurveyOutputServlet):

Year Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Annual

2006 34.5 34.5 34.5 34.7 34.5 34.4 34.5 34.5 34.5 34.8

2007 34.5 34.5 34.6 34.7 34.7 34.7 34.6 34.5 34.6 34.5 34.6 34.7

2008 34.5 34.5 34.7 34.6 34.6 34.6 34.5 34.4 34.4 34.4 34.3 34.2

2009 34.2 34.1 34.0 33.9 33.9 33.8 33.8 33.8 33.8 33.7 33.9 33.8

2010 34.0 33.9 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.2 34.3 34.3(P) 34.3(P)

P : preliminary

I said “work harder” , not “work longer”. I think that is what higher productivity means.

Also “Kurzarbeit” doesn’t always mean less hours. From Wikipedia:

“If an employee agrees to undergo training programs during his or her extra time off, they can often maintain their former income”

So effectively this means “work less hard”.

Your second “fake” explanation is actually quite good. But that doesn’t help the workers.

So the difference is all about choice.

Off topic: I always try to guess whose post I’m reading and never look until I get to the end. Usually I’ve made up my mind in the first few sentences, and generally I’m right. Sure, topic often gives it away, but your individual voices are strong clues too. This one had Nick written all over it.

These graphs are an exemplary demonstration of what the “hire and fire”, weak safety net US workforce experienced during the crisis, versus the strong, unionized, Kurzarbeit-supported workforce in Germany.

The takeaway is that being unemployed in the US is a sticky condition. Once a worker ‘falls out of grace’, the chances of getting work again dwindle with every passing month and year. The US stats are in fact optimistic, real unemployment is probably well above 10% – it’s just that whole categories of workers have stopped looking for jobs in a trackable way – the benefits time out after ~55 weeks and the prospects are not good.

Contrast that with Germany where it is being employed that is sticky: the country ‘buffered’ workers in the Kurzarbeit government safety net and had them ready and well-motivated by the time the crisis is over. And Germany is now kicking the pants off the US …

The US policy is a heartless right-wing approach to those supposedly freeloading, benefit-seeking unemployed workers who are really just caught up in a ‘recalculation’ or some other structural shift that is their damn fault.

The German policy is to buffer pre-crisis capacity and structure, which assumes that the pre-crisis structure is more or less ready for post-crisis growth.

The graphs tell us a clear story about which policy approach was right economically – let alone socially and morally …

It’s sad in a way, seeing how self-righteous the US conservatives are about all this. They have no sense of responsibility and they have no sense of shame.

Btw., another factor that should be considered are the exchange rates.

The US was pretty much special in that regard, due to the USD being the reserve currency of the world it had an unprecedented inflow of capital during the 2008 crisis.

That strengthened the USD massively – hurting export sectors.

Europe on the other hand had a debt crisis in 2009 which weakened the EUR.

The USD was also kept artificially strong by the chinese buying tens of billions of dollars every quarter, via their massive trade surplus. That predatory mercantilist approach of the chinese kept the dollar artificially strong and the yuan artificially weak – again hurting US exports. (The weak yuan also hurts Europe and the rest of the world.)

Can you extend these graphs back a couple of decades?

My concern with these particular stats is that U.S. employees will jump through whatever hoops they need to in order to NOT lose the relationship with their employer because of the high incidence of employment-based health insurance plans.

If the “rest of the world” (or at least, the rest with some form of public health insurance or public health care) has a more pure labour market, then when declines in employment ought to happen, they do. But for the U.S., I would theorize that there was an overhang of excess employment because of the health care situation. This recession finally forced the separation of those employees, correcting the overhang. The result in recent stats would be the appearance of a sudden persistent drop in employment, that doesn’t seem to be subject to the recovery.

The way to find this would be to extend these curves backward. You likely have to move the sync point as well. It might then appear that the U.S. is normal now, but for years had an “employment bulge”, possibly not matched by GDP.

Can you extend these graphs back a couple of decades?

Sure, but then we’d be talking about long-run trends in productivity and not what happened in the recession.

eta: Anyway, the employment situation through the 2000’s was pretty weak. The US never really recovered from the 2001 recession.

Clearly the jobs market remained sluggish because the minimum wage was raised.

What about outsourcing? Apple’s value add is in design. The government announces a stimulus, and Apple picks up the phone and orders another million iPods from China. With a value add of $200 per iPhone sold, productivity goes through the roof, but employment doesn’t pick up by all that much.

What RSJ said.

This might be a mystery empirically, with respect to the actual detailed data, but in principle I don’t see the puzzle. Consider Ryan Avent, who quotes Rob Shimer as saying: “take any given group within the labour force, and the crisis has essentially generated a doubling of the unemployment rate” (http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2011/01/labour_markets.)

One way a uniform geometric increase in unemployment could produce an unexpectedly small decline in GDP is if the original unemployment rates were heterogeneous. Suppose, hypothetically, that high-income occupations have much lower unemployment than low-income ones. Doubling unemployment for both depresses employment much more than GDP, because GDP is a function of employment, not unemployment, and employment has not been scaled uniformly.

You might reasonably ask how such a situation could come about – why don’t people move from low-income occupations to high-income ones? (More employment and more pay! What’s not to like?) I’ll leave that for another day, except to observe that the facts suggest this transition is not so easy.

What Phil said.

I’d like to agree with RSJ about outsourcing playing a large role in the US having a different response than the rest of the G7, but why isn’t this outsourcing effect seen more broadly? Are US firms the only firms that outsource, and if so, why? If you’re going to rely on the outsourcing story, I think you’ll need a ws and White Rabbit “Kurzarbeit” type program to explain why European nations have not outsourced their jobs.

I’m also struck by the record profits generated by US corporations last quarter as the unemployment rate hovered just below 10%. I seem to recall that the record profits were generated by two groups: either multinationals or financial firms. Growth by multinationals would be measured in the GDP, but the attendant growth in jobs would likely occur overseas.

Meanwhile, I believe financial firms contain a disproportionately high number of high-income occupations (or conversely, relatively few employees for the GDP produced, echoing Phil Koop’s comment). So the growth in this sector after the sell-off in 2008 would help explain the bounce in GDP but the lag in employment.

I’m not entirely convinced by these explanations but it’s a start.

i’d go kalecki here.http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2009/11/zomfg-wtf-95-third-quarter-productivity-growth-number.html

Kosta,

It’s not that U.S. firms are the only ones that outsource, but other nations are constrained by the current account in a way that the U.S. is not.

But I think Phil is “more right”. He is making the general point that GDP = GDI, so when GDP doesn’t fall as much as employment, you have the simple explanation that low wage jobs are being shed rather than high wage jobs. In that sense, my explanation is just one mechanism by which this can happen — low wage jobs aren’t needed as much to increase GDP.

But then why specifically in the U.S? The current account (and reserve status of the dollar) seems to be the clear outlier.

But you can also argue that the U.S. is an outlier in terms of labor power, and so that is the reason why G7 nations need low wage jobs in order to produce GDP whereas the U.S. does not.

I’m not sure how you would determine which explanation is right, or to what degree each is right. The two seem to go together.

It’s definitely the case that job shedding in the States disproportionally impacted lower wage workers, which could have been driven by dollar power (exports got nailed, higher wage industries didn’t, Apple being a key example of recent high wage success).

The difference with Europe doesn’t surprise me because European social welfare systems are designed to make workers difficult to fire, which is basically a GDP / employment tradeoff: inefficiency hurts GDP, but employment is preserved close to its (already low) pre-recession levels.

My big question then is, were low-wage jobs shed disproportionately in the States as compared to Europe? If so, that’s a pretty good argument for this story.

The comparison with Canada is more confusing: strong currency and dynamic labor markets, like the US, plus Canada had high exposure to resources (which tanked), so what the hell? But since Canada did the best in terms of both GDP and employment, answering why it did so well would probably tell you why its productivity was flat too.

Nathan Tankus: thank you for the link.

I think Kalecki (as told by Delong) is right.

But I would add that this works even if it is not intented by the employer.

Suppose you are an employee.

A recession begins. Your employer fires 10% of your colleagues.

You are one of the lucky 90% that can stay. What do you do?

Do you keep having a coffeebreak of 20 minutes instead of the official 7 minutes?

Are you even going to wait untill your boss makes a remark about it?

Does it make a difference if there is a safety net ?

Does it make a difference if politicians argue about reducing the safety net ?

I am not saying that one system is better than the other. I am only trying to explain the differences.

The flip side in Europe is probably higher structural unemployment.

But as a society we have a choice.

not sure of the arithmetic, but how would lower resource prices affect productivity measures?

Garrett Jones had an interesting explanation:

The recession is a period of low investment–that includes sub-normal investment in organization capital. Consequently some workers become separated. Output holds steady but employment declines. Maybe future output declines too. The organization capital otherwise produced is not measured at its true value by GDP, as only the cost of the worker appears in GDP not the surplus captured by the firm. A more comprehensive measure of output would show a larger decline, OR Output rises relative to other countries and compensates because MC declines: Low productivity workers get laid off. Investment slows, so high productivity workers get re-tasked to producing immediate output.

This latter story comports with my experience in the business world.

You can argue that it is the social safety net in other countries, but that does not quite ring true as the whole truth. Perhaps a contrarian view would be that US business operates in a different way to business in other countries. Having worked for companies around the globe this certainly as some truth to it. In response to a recession I would expect German companies to improve efficiency by by investing in new machinery and developing better products. In response to a recession I would expect French companies to improve efficiency by developing a grand plan and investing in their people. In response to a recession I would expect UK companies to focus on customer service, squeezing out costs and selective investment in business bottle necks. In response to a recession I would expect Japanese companies to focus on developing better products, investing in their people and squeezing out costs.I am not familiar with canadian companys but I suspect they are similar to UK companies. In response to a recession I would expect Italian companies to target product development and papering over the cracks until better times.

In response to a recession I would expect US companies to shed workers and shutter plants.It would be my contention that world business sees workers as a valuable asset while US business sees workers as a resource to be chopped to size. Now look at the responses and ask yourself which of these improves competitivness on a longer term basis. Having said this there are other aspects to US business which I tend to admire.

I see this as a story of openness and stimulus. All of these countries are much more open than the US.

Japan and Germany, being on the extreme end of openness, had a GDP collapse due to a trade collapse.Canada would have too had it not been bouyed by resource prices.

France and the UK both had fairly aggresive stimulus programs (well, the UK did before the austerians took over – look for the UK to fall behind the pack).

And Italy has of course just muddled along as any country saddled with that much debt must do.

And, being a recovering American, I can tell you that I’m pretty sure ws is right: in a fairly closed economy like the US with a miserable safety net what choice do workers have but to sweat blood to keep their jobs?

Difference in the way statistics are collected when it comes to unemployment.

Workers are hired when firms expect growth. When this growth does not materialize workers have to be laid off. The drop in GDP should be measured against the expectations of GDP-growth. The problem is that this is difficult to operationalize in a way so that all observers agree.

Openness, is not a good explanation as it could go either way.

The explanation, is not an explanation perse, merely an observation that the accounting identity holds. The question is what is the relationship that determines that the new equilibrium settles where it does.

The difference in social safety (counter-cyclical) net should be visible in the steepness of GDP decline. Why does Canada hold up so well compared to the other ‘social safety net’-countries?

What if a shift from construction to manufacturing is a shift from low productivity employment to high productivity employment? I can easily see boeing workers building planes for exports producing a lot of output per worker. I am not so sure I understand why construction workers no longer producing houses like they did in the boom don’t involve a lot of sacrific of output.

Also, layoffs continued at the usual rate for the most part (there was a big spike in the spring of 2009.) The drop in employment, however, is almost entirely a matter of the normal rate of separations, and unusually low hires.

If other countries have less churn in the labor force, the normal layoffs and restricted new hires won’t cause as much loss in employment. (I don’t think.)

Of course, my bottom line is that when NGDP is back on the 1984-2010 trend, come back and we will discuss employment, RGDP and productivity.

Brad Delong comments on his blog:

http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2011/01/the-end-of-procyclical-labor-productivity.html

The answer could be very simple: one could posit that a lot of the formerly employed people added so little value to the enterprise that their departures were not felt as a decline in aggregate output. Under this assumption, remaining workers would not have to “work harder” or “work longer” to maintain aggregate output. Assuming essentially the same aggregate output by the remaining employees, the result would be (1) apparently increased productivity, even though no remaining individual was indeed more productive (2) essentially the same GDP and (3) declining employment.

Another possible explanation is that aggregate output is maintained by outsourcing to foreigners. Their production is added to the company’s domestic production, but they are not added to the company’s payroll. Result: it appears that fewer employed workers have been responsible for the same output as when a larger body of workers was employed.

Social welfare costs born by companies have no bearing on GDP figures, and the lack of employer-sponored welfare programs does not contribute to unemployment. The existence of such programs does help explain why companies find it relatively more costly to keep marginally productive workers on the payroll.

RSJ, you wrote: “but other nations are constrained by the current account in a way that the U.S. is not.”

I don’t understand what you mean by this (call me dense). Maybe I’m just not sure how the current account constrains a country like Germany? I think you’re onto something by focusing on the US’s exceptional current account and reserve currency status, but I can’t make the connection to increased productivity. Undoubtedly, offshore outsourcing has played a role, but the US’s lower labour standards must be important as well.

Comparing Canada to other G7 nations might be inappropriate given the dependency of the Canadian economy upon resources. Perhaps Australia and New Zealand should be included in the mix. Of course, those latter two economies are much more dependent upon Chinese economic growth, but their addition might be insightful.

Patrick: Brad Delong doesn’t answer the question. He only rephrases it:

Why has US productivity become more countercyclical than elsewhere ?

This is not going to get better, until the conventional wisdom changes. For it is conventional wisdom which destroyed the Great American Jobs Machine. These graphs reveal how well and truly dead it is.

What we are witnessing is the agonizing death of the conventional wisdom. The fixes applied to the financial system by the Obama administration had the unfortunate side effect that the conventional wisdom staggers on, undermined by not destroyed by the unemployment crisis.

So it will only be through a war of attrition that the conventional wisdom is dismantled. How long will it take before there is legislative action wrt industrial policy, outsourcing, destructive job market effects from free trade agreements, easing unionization? Years. Yes, years. And all the while the crazies won’t be going away, nor the vitriol, nor the guns. Strap yourselves in for a rough ride.

Paul Krugman gives the answer in the second paragraph of his piece on the euro:

Try charting Ireland and Spain. The hypothesis is that all three nations endured a housing bubble, and therefore, due to the inventory overhang, employment in construction is impaired.

Kosta,

In this simple example, the Government announces a stimulus of $600. Apple sells an additional iPhone for $600, but little additional hiring occurs since the iPhone is made overseas for $100, and apple, on the margin, only needs to hire a few more sales staff, for example. So employment goes up by 1 hour, and GDP goes up by $500.

That assumes that, on the margin, imports rise by $100 with no corresponding rise in exports. That is possible only if the rest of the world is willing to accumulate U.S. dollar assets — the government sells $600 of bonds, of which $100 are accumulated by the exporters.

If that was not the case, then U.S. exports would need to rise by $100 (requiring additional hiring), or Apple’s input costs would rise due to the depreciating dollar, (and their value add, or contribution to GDP, would fall for the same reason).

In either case, the deviation between the change in GDP and the change in employment would be less than if the nation was unconstrained in its current account.

ws: I never claimed DeLong provided an answer.

David:

nice point about countries with housing bubbles seeing increased unemployment from the construction industry. On the other hand, didn’t the UK also have a housing bubble (albeit somewhat smaller)? Their employment has had a better bounce back.

RSJ:

Thanks for the example. I see what you’re getting at with the U.S. being able to run a higher current account deficit and therefore about to outsource. On the other hand, shouldn’t surplus countries like Germany always be in the position where they can outsource? The outsourcing might even cause a depreciation of the German currency, but wouldn’t this be good for sales/exports and increase GDP? So why didn’t Germany exploit outsourcing over 2008-2010?

What you see in the graphs can’t plausibly be explained in terms of short term interactions between labor input and GDP output. It’s more like the bobbing to the surface of a larger portion of the tip of a long term ‘iceberg’. The iceberg in question is the chronic miscalculation of national income and product accounts that Simon Kuznets identified in his scathing 1947 critique of the Commerce Department’s first release of the series. Stefano Bartolini and Roefie Hueting have offered more recent updates of the criticism.

What Kuznets decried was the inclusion of vast swaths of what he argued were really intermediate goods and thus should not added into the accounts because that would constitute double counting. Hueting and Bartolini have each modified the double-counting charge to also include what Hueting refers to as “asymmetric entering” and Bartolini as “negative externality growth”.

Although there is undoubtedly a large component of asymmetric entering or negative externality growth in the GDPs of all G7 countries, as indeed of all countries, the USA stands out as the country that has worked the hardest to make a “virtue” of social-accounting malfunction through its military-industrial and medical-pharmaceutical complexes and its horrendously bloated finance, insurance and real estate sector.

(Cross posted at Grasping Reality)

A couple of blind stabs:

Perhaps change in unemployment isn’t quite the right measure. If countries with more rigid labor markets started with higher unemployment to start with then lower marginal productivity workers could already be out of work. If both overall unemployment rates and production per hour worked converged that might be plausible.

Also, the composition issue raised above strikes me as plausible if unemployment in the US is disporportionately born by lower earning workers compared to other G7 nations the GDP would be less affected than those countries.

For example, if the economy had 20 employees making 100K, 50 employees making 50K and 30 employees making 20K, GDI = 5,100,000. Unemployment is 0%

If 10 20K employees are rendered unemployed then GDI = 4,900,000 a 5.9% decrease, but a 10% increase in unemployment.

I do know that unemployment in the US is concentrated among those with lower educational acheivement, I don’t know to what extent this is true of other countries. Though, if it is different, why is that?

Lastly, I assume this is real GDP, how does NGDP change vs inflation look?

David Fitzsimmons: The UK is there, and they had a housing bubble, and it looks more like France than the US.

Just to be clear, the first graph is nominal GDP? Or real GDP? The distinction seems important here. I suppose I would like to see both.

It’s real GDP.

I’ve always wondered about people talking about unemployment as bad and job creation as necessary but haven’t really found qualified people to ask about it. Happened on this post and I think someone here can help me understand from the level of the article and the replies.

If we can produce all the same stuff without it, shouldn’t we just work less? With better infrastructure and increasingly advanced manufacturing isn’t it inevitable that there won’t be enough work to go around and the best we can do is try and delay this transition while we think of something?

I almost switched to a 3 day week myself to do my part. Stuff is so cheap that you really don’t need a lot of money to live very comfortably. People are just insane and think they need more than a warm roof, A to B transport and good produce from the grocery store. Another way I find life very affordable is buying really high quality goods that last me decades and often buying those used.

Are there any groups working on making this transition for developed economies? The extra free time would actually increase consumption, no? And less hours billed means companies are more efficient at producing stuff to fill that time? Or am I missing one or three huge things and the world is not at all as I see it?

Obviously, the workers who are now unemployed were not very productive. Otherwise, the US would not be able to maintain it’s GDP. Everyone knows someone who shows up at work every day and does nothing. Looks like US companies have dropped a lot of dead weight.

“If we can produce all the same stuff without it, shouldn’t we just work less?”

Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes! But truth be told, the idea is heresy to economists — heresy! — because the thought that “there won’t be enough work to go around” is a Fallacy (with a capital “f” because it’s “one of the best known fallacies in economics”).

There’s a very old idea in economics (310 years old at least) that free trade or new machines or other improvements in productivity will always lead to more jobs in the long run because the cheaper prices will increase effective demand.

There’s another idea, not quite so old, called the Jevons Paradox or rebound effect that improvements in energy efficiency will lead to more, rather than less, total consumption of fuels.

Those two ideas are actually the same idea. But one version of it implies that growth is unlimited while the other version implies definite limits to growth. So what we have here is a paradox of paradoxes. The solution to the riddle (and it’s really more of a riddle than a paradox) is… we just work less.

Okay, so if working less and having goods and services to meet demand is viable, how do we get from here to there?

Right now if I tell someone “Hey, you can make the same amount but work 3/5 the time and spend the rest of it enriching yourself and your family!” just as likely as not they’d respond “Ya… or I could make 2/5th more for doing exactly what I’m used to”.

How do we overcome that and is anyone planning for it at all or is it just going to be a big mess? Is it even possible to plan for?

Does working less and producing the same create economic growth through additional leisure time in which to consume?

Does it create more opportunity for interesting diversity in the market as there is a greater pool of possible entrepreneurs once free time is a common thing?

For those reasons, would countries that do this first get an edge somehow in the long run or is that same “yah, you do that, I’ll keep working and get a bigger slice of the pie” logic applicable on the national scale too?

Is there a good book or three that tackles this rather than just trying to reconcile it with existing thinking and models?

Try charting Ireland and Spain.

Interesting idea. Here’s employment and GDP. Haven’t looked too closely at them, but Ireland is just dreadful in both graphs, and Spain isn’t much better.

harmless,

Well… I just happen to have the horse right here! (in the form of the manuscript of a book, no less). The book is called Jobs, Liberty and the Bottom Line and it outlines the institutional and social-accounting arrangements that could facilitate a transition to the “leisure society” (leisure being understood as self-directed activity, rather than as entertainment and idleness).

http://ecologicalheadstand.blogspot.com/p/jobs-liberty-and-bottom-line.html

That’s my long answer to questions 1 and 5. The short answer to your questions 2, 3 and 4 is: just like any innovation, it depends on how well it’s designed and implemented.

Harmless: if productivity doubles, and people decide to consume the same amount of goods and work only half the time, they are not unemployed. “Unemployment” means “not working and looking for work”

The demand for labour halves, and the supply of labour halves too. No problem. No unemployment.

No “heresies”, no “fallacies”, no nothing. A doubling of productivity means people can either consume twice as much, or work half as much, or any combination in between. Historically, most people have chosen to work a little bit less and consume a lot more.

Stephen. Spain is even weirder than the US! Employment fell much more than GDP. A big increase in productivity!

Construction?

I wonder if it has to do with the way those GDP numbers are calculated. I don’t know much about how it’s done, so this may be all wrong.

They can’t be just comparing values of output between countries based on exchange rates, because that would be subject to change as currency values fluctuate for all sorts of reasons, including manipulation and speculation. Presumably, they must be trying to get some kind of “real” output, using some kind of GDP deflator or something.

So what happens if they use a deflator that includes house prices? House prices go down in the U.S. more than elsewhere, so it looks as if the “price level” has fallen or not risen as fast as it would have otherwise, Then, when they calculate the value of what is produced and “correct” it with that deflator, the value of all the other things produced looks good.

It looks to me as if Spain and Ireland might show a bit of a similarity to the U.S. GDP looks slightly less relatively disasterous than employment to me.

Nick: So really the disparity in the graph above is more of a cultural problem than an economic one?

“Historically, most people have chosen to work a little bit less and consume a lot more.”

That’s true — except “history” appears to have stopped in the U.S. sometime around 1980. And it had slowed down a heck of a lot in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s.

In 1958, BLS economist Joseph Zeisel called the long-term decline in the industrial workweek, “one of the most persistent and significant trends in the American economy in the last century.” Yet the average manufacturing workweek in March 2010 was six minutes longer than the average had been for August 1945.

In the broader economy, if the trend of annual hours worked that had prevailed from 1909 to 1957 had persisted, average annual hours in 2009 would have been 14% lower than they were. They could have been even lower than that, taking into account the sectoral shift into the service sector (where hours are traditionally shorter) and the much increased labor force participation of women with young and school-aged children.

Robert Reich argues that it was the stagnation of wages that drove the increase in two-income families. I tend to view it as a question of the stagnation of hours driving the stagnation of wages.