Stephen's got standards. So I'm going to steal his graphs from his last post, and write the post he could easily have written.

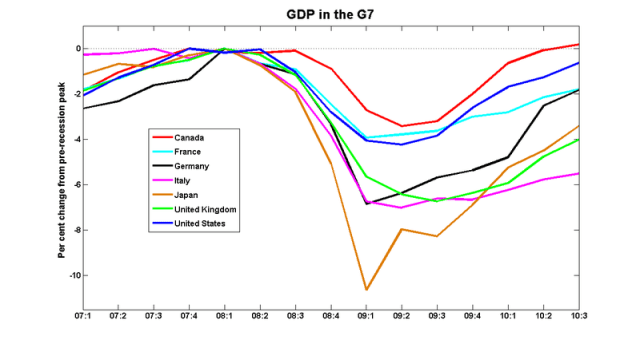

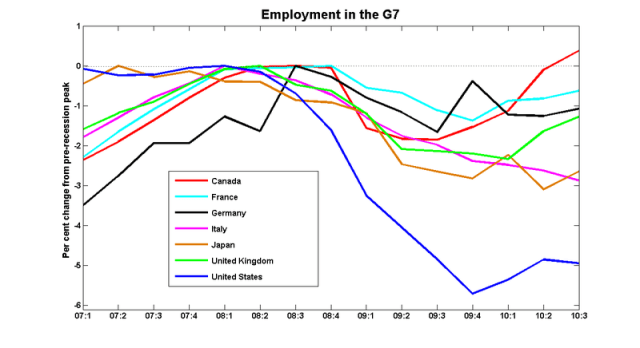

Before you look at Stephen's graphs, ask yourself this question. How well did the US fare in the Great Recession, in terms of GDP and employment, compared to other G7 countries?

Now look at the dark blue lines (that's the US) in both graphs. Compare them to the other lines. Did you see what you expected to see, on both graphs?

OECD data in both graphs.

I could understand if the US had the worst output and employment during the recession. I could fake up some explanation. "The US, with the bursting of its house price bubble, was the epicentre of the financial crisis, blah, blah…".

I could understand if the US had the best output and employment during the recession. I could fake up some other explanation. "The US, with its free market economy and labour mobility, is remarkably resilient to shocks, blah, blah…".

What I can't understand is why the US had the second best output, and yet by far the worst employment. That would require two fake explanations, and it would be hard to make those two explanations consistent.

Each of us thinks our own country is normal. We try to explain why other countries are different. That's especially true if our own country is a large country, like the US. But when you compare the US to all the other G7 countries, you see that it's the US that is abnormal, and in need of explanation.

Ignore the US in Stephen's graphs, and everything looks normal. Some countries did worse than others, and the countries that did worse on GDP tended to do worse on employment. You get roughly the same ranking on either measure. Moreover, the decline in GDP was about two or three times as big as the decline in employment. That's what we would expect, from Okun's Law. It's the US that doesn't fit the pattern. The US is abnormal, and in need of explanation.

Okun's Law tells us that labour productivity, crudely measured as GDP/employment, and ignoring subtleties like hours worked and quality of labour, normally falls in a recession. Because the percentage fall in GDP will be two or three times as big as the percentage fall in employment. And it did fall in all the other countries. But in the US it didn't fall at all. Labour productivity actually increased. GDP fell a little over 4%, peak to trough, and employment fell nearly 6%, so the GDP/employment ratio increased by over 1%.

The US is an even bigger puzzle if you think that business cycles are caused by productivity shocks. Sure, you could always argue that US firms and workers were expecting even bigger productivity growth, so when it actually came in at only 1%, that was a negative shock to productivity. But you would have to work hard to convince me that that's plausible. And what were all the other countries expectations for productivity growth — chopped liver?

Why did US productivity increase during the recession? Why doesn't your explanation also apply to the other 6 countries?

Why is the US an exception?

Nick: I guess it does look like one could put together a story revolving around overbuilding, a collapse in construction employment and difficulties shifting employment from construction to export-oriented sectors. In both countries, the obstacle is trying to engineer the necessary depreciation. Spain is stuck with the euro, and the US is stuck with the yuan peg.

But I don’t know how to get increased output/employment ratios out of that story.

Stephen:

Okun’s Law has always been the puzzle. Why should productivity decline in a recession? The standard answer (for Keynesians and Monetarists) has always been labour hoarding. Aggregate Demand falls, firms don’t need all the workers, because they can’t sell the output, but firms don’t fire them, because it will be difficult to hire them back again when demand recovers. So it keeps the workers on the books, but not really working.

Why should construction be different?

A1: because construction workers have general human capital rather than firm-specific human capital. So it’s easy to re-hire when demand returns.

A2: because the construction firms know that demand won’t return for decades.

harmless: forget the graphs. What you are talking about is the improvement in productivity that happens over decades, and how people choose to respond to it. The graphs are an economic puzzle about the short run.

Spain is really really weird. Much weirder than the US. Spanish productivity increased by about 5%-6%!!

It has to be a combination of two things: the absence of labour hoarding (that explains why productivity didn’t fall); plus, construction has lower productivity than the rest of the economy(????) (that explains why productivity rises when you destroy the construction sector.

Time for a new post “Spain is even weirder than the US”?

“But I don’t know how to get increased output/employment ratios out of that story.”

The mystery dissolves if you distinguish between wealth, understood as goods and services produced for final consumption by individuals, and claims on wealth. Statistically, it’s not easy to make those distinctions because, for example, some financial services are indeed services while others are hocus pocus (see Inside Job for examples). Back in the 1930s, when productivity estimates were first being made, the economists relied on physical outputs and it took long lead times before the data became available. Then, when the Commerce Department started issuing quarterly national income accounts, the switch was made from physical outputs to money transactions deflated by a price index, so much more timely analysis and tracking could occur.

People seems to forget that any gain in expediency is accompanied by a loss in depth and accuracy. The joke here is that however much people may want the numbers themselves to tell a story, there is also a meta-story about the numbers and how they came to have the characteristics they have. When the story the numbers tell is contradictory, it’s a good time to go back and look at that other story. Here’s a few suggestions:

“National Income: A New Version,” Simon Kuznets, The Review of Economics and Statistics, Volume XXX, Number 3, August 1948. See especially pages 155-160.

“Objectives of National Income Measurement: A reply to Professor Kuznets,” Milton Gilbert, George Jaszi, Edward F. Denison & Charles F. Schwartz, The Review of Economics and Statistics, Volume XXX, Number 3, August 1948. See especially pages 182-189.

“The Conceptual Basis of the Accounts: A Re-examination,” George Jaszi, in A Critique of the United States Income and Product Accounts, NBER, pages 13-148. See especially pages 69-76.

“Extended Accounts for National Income and Product,” Robert Eisner, Journal of Economic Literature, Volume 26, Number 4, December 1988, pages 1611-1684.

“The Politics of Social Accounting: Public Goals and the Evolution of the National Accounts in Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States,” Mark Perlman & Morgan Marietta, Review of Political Economy, Volume 17, Number 2, 211-230, April 2005.

“Accountants and the Price System: The Problem of Social Costs,” Donald R. Stabile, Journal of Economic Issues, Volume XXVII, Number 1, March 1993.

“Productivity as a Social Problem: The Uses and Misuses of Social Indicators,” Fred Block and Gene A. Burns, American Sociological Review, Volume 51, Number 6, December, 1986, pages 767-780.

“Environmental and social degradation as the engine of economic growth,” Stefano Bartolini and Luigi Bonatti, Ecological Economics, Volume 43, Issue 1, November 2002, Pages 1-16.

“Why environmental sustainability can most probably not be attained with growing production,” Roefie Hueting, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 18, Issue 6, April 2010, Pages 525-530.

Chris S said: “Can you extend these graphs back a couple of decades?”

Maybe not the exact chart you are looking for but try this link with Yves Smith:

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2010/12/we-speak-on-real-news-network-about-stimulus-and-tax-cuts.html

The chart is at about the 5 minute 30 second mark and titled productivity and average real earnings.

I’d listen from about the 4 minute and 15 second mark to about the 7 minute mark.

“The US is an even bigger puzzle if you think that business cycles are caused by productivity shocks.”

more like “… caused by positive productivity shocks and other things that cause price deflation and not handled correctly in terms of the medium of exchange.

Yep. I think David Fitzsimmon’s suggestion was a great one!

Stephen – I know you said it was “OECD data” but can you be a bit more specific? The OECD stats page never seems to want to give me monthly stats, and there is more than one variant of GDP.

I can do a bunch of the grunt work of getting stuff, but references to specific data sets, and maybe a starting URL would be helpful. Of course, if the data is the really detailed good stuff that came via a University subscription of some kind, that might mean I can’t repeat these myself.

I got them from here:

http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx

No subscription necessary. The GDP data are of course only available at the quarterly frequency, and some countries – Germany, for example – don’t seem to have monthly employment data.

eta: Yes, there are different variants. I used the ones that corresponded with the series StatsCan publishes.

The US, Ireland, and Spain, faced a collapse in demand due to the destruction of credit. They were operating on a model of debt-financed consumption, fuelled primarily by their housing bubbles. Their housing markets crashed and with that went the HELOCs and the investment properties, etc. For more on this, try Steve Keen. He has working dynamical models of modern economies where final demand is equal to GDP plus the change in debt.

The bottom line is that Canada is still expanding debt. The government backstops virtually all new mortgages. Hence all the warnings from Mark Carney about how 10% of the population will go under if interest rates rise 1.5%. The problem will continue to get worse every year, but eventually we will hit the same wall where a lot of consumer debt can no longer be financed, let alone repaid. Then we’ll understand a bit better what happened in the US. Australia is hitting this wall right now.

One thing that will be different is that when banks foreclose in Canada, the government is automatically liable for any difference between value of the mortgage and the market value of the house. So you’d better pray the housing market does not revert to anything like the historical mean with respect to incomes or rents. If it does this country is cooked.

To me a big increase of productivity in Spain is not at all weird.

Where else do you have a 3 hour lunch break (from 2 pm to 5 pm)?

see e.g. http://gospain.about.com/od/spanishlife/f/siesta.htm

Time enough for a barbecue (and cheap wine).

What do you think the productivity is in the afternoon (i.e. after 5pm)?

Seems there is room enough for improvement.

Do you wonder why the punctual Germans are not eager to bail out Spain ?

Oooh. I think the bad accounting is the answer. The US has an especially bloated “useless” sector — financial, military, etc. — and an especially high tolerance for accounting fraud. In other words, the GDP numbers for the US are simply lies.

The siesta is an accomodation to the weather. What do you think productivity would be from 2-5pm given the weather? I would expect most people to spend some of that time sleeping, which kicks the productivity post siesta up.

European labour market regulation does what regulation so often does: it protects incumbents. (Young people were already significantly locked out of employment, this has got worse.) Since the risk of hiring new folk is much higher, European employers take more action to retain “known quantity” workers. US employers are much more confident about hiring new workers, so are much less concerned with retaining existing workers. So, ceteris paribus, European employment drops less in downturns. The cost is that their employment growth is (much) lower over the long term.

As for the rest, the Fed did it. The dramatic, unexpected drop in inflation made a lot of employment contracts “badly priced” in real terms and wages are sticky, but US employment is not. While the shift upwards in expectations about the future value of money in a situation of considerable uncertainty and credit problems choked off a lot of investment, further discouraging employment. In a “de-leveraging” economy with flexible employment, labour is what got shed.

This labour market segmentation in favour of incumbents is also why Europe had lower falls in employment, but a lot more riots.

America has virtually no labor movement left and very little in the way of labor protection compared to other G7 nations. I believe that a large percentage of the workforce is simply working more hours for the same pay as before. I personally know of many people who work 50+ hours when before the recession they used to work 40 hours per week. Most corporations have had layoffs, and after that happens the remaining workers will generally do whatever it takes too keep their job, especially when the labor market is so awful. This doesn’t show up in BLS data because these hours are off the books. A huge percentage of the population just accepts employer wage theft, because the alternative is no wage at all. Productivity per worker is now exceptionally high, and capital is laughing at labor all the way to the bank.

There are a lot of plausible suggestions in these comments. The US is different from the other G7 countries in lots of ways. How to tell which one is right?

The only way I can think of is to increase the sample size. Stephen’s new graphs, following David Fitzsimmons’ suggestion, show that Spain is just like the US, only even more so. And Ireland is a bit abnormal too. What do these three countries have in common? It’s not siestas, and it’s not labour laws and social safety nets. I think it’s a big construction slump.

See my new post.

rp: Why is the country “cooked” if banks only get current rates + 1.5% on their mortgage investments? They don’t have to forclose on everyone, it wouldn’t be in their best interests to cause that much instability. Just because they can raise rates doesn’t mean they have to?

Would it be catastrophic if they simply treated it as if they bought rather too many long term bonds at a coupon rate below what it ultimately was but based new lending on the current prime? They might be less globally competitive but would that not be offset by the comparative stability in our economy as a haven from risk (opposite the historical view) in what would presumably still be quite tumultuous times?

“The bottom line is that Canada is still expanding debt. The government backstops virtually all new mortgages. Hence all the warnings from Mark Carney about how 10% of the population will go under if interest rates rise 1.5%. The problem will continue to get worse every year, but eventually we will hit the same wall where a lot of consumer debt can no longer be financed, let alone repaid. Then we’ll understand a bit better what happened in the US. Australia is hitting this wall right now.”

Sounds like somebody’s listening. Today’s Financial Post:

http://www.financialpost.com/personal-finance/Tougher+condo+mortgage+laws/4105580/story.html

“Sources say rules now being discussed would add 100% of condominium fees to the list of expenses that is measured against income to decide whether a buyer can afford a mortgage. Currently, only 50% of the fee is considered. The move has the potential to squeeze thousands of consumers out of the market.”

Or maybe the market for high rise shoe boxes will come down to a more rational level?

I like Nirad’s comment.

Could it be that many Americans are working a lot of unpaid & undeclared overtime?

Also, US inflation statistics are kooky, one reason (of many) being because they take into account increasing raw processor speeds of computers without taking into account the counter-productive effects of software and operating system bloat.

There’s no mystery here. Corporations simply adjust their head counts on the basis of revenues and non-payroll expenses in order to meet financial ratio targets. Revenues drop, employees get deleted from the payroll until the sales per employee ratio meets the target value.

And there was a huge spike in energy prices here in the USA in 2008, right around the time the employment started to drop precipitously. Fuel costs rise – to balance out the energy cost increase, workers are deleted from the payroll. Fuel costs rise, automobile sales plummet – auto workers are laid off.

There’s no mystery here – you’re simply not looking at all the time series or taking into account the feedback loops by which corporations are managed. Was there a huge spike in energy prices in the other G7 nations in 2008, or was the USA the only one hit?

Energy prices rose everywhere; we all buy oil from the same world market.

As predicted, this post has generated some noise in the US blogosphere, but many seem to be missing Nick’s point. For example, what is so special about the US that it has zero marginal product workers while that’s not the case elsewhere in the G7?

The graphs paint a very simple picture to me; we Americans have trimmed payroll fat that was contributing little or nothing (in aggregate) to our GDP. True, fewer workers are doing more just to sustain output but the disparity in GDP vs. employment shows that it was far from equilibrium going into he recession. If it were, a precipitous drop in employment would have had a lock-step drop in output…but it didn’t so our companies (not necessarily the country) are better off (in aggregate). As for those who lost their jobs – what a great chance to re-train, start a business, invent something….innovate!!!!

That answer begs the question of why that didn’t happen in other countries. Moreover, US employment growth in the decade preceding the crisis was fairly anemic; hard to see how much fat could have accumulated.

Interesting.

The post is about US productivity growth. Yet only the two components of a an aggregate GDP/labour productivity ratio are furnished in chart format. I guess blog-discussion participants are sufficiently numbers-experienced to readily estimate-imagine the 3rd latent chart. As for non-economists?

Would be interesting to see similar numbers for the USA broken down by sector (business, manufacturing, and public).

Take cover! Krugman link incoming

Here’s a colleague that argues that the 1981-82 recession is not any different that 2007-09 recession in terms of labor productivity.

http://www.econ.upenn.edu/~manovski/