It is the conventional wisdom that urban centers with their concentrations of human and physical capital and their dense social networks are engines of growth. One exception to this is can be the case where a dominant urban center by virtue of its institutional monopoly on a country or region’s economic life is able to extract economic rent from the surrounding country side and ultimately kill the goose that laid the golden egg.

Alan Beattie, in his False Economy: A Surprising Economic History of the World, discusses urban centers and growth and mentions the combination of large cities that are political capitals, which gives them the “ability to punch well above their political weight”. Historical examples show that in capital cities, it is difficult to ignore the wishes of the disgruntled, because their proximity makes them difficult to ignore. Beattie points out that in strong democracies, it makes little difference where “malcontents” live but in weak democracies it can be a critical factor especially if they live in a large urban center that is also a capital. The classic example is probably imperial Rome where rent was extracted from an entire empire to maintain the urban population with bread and circuses.

The potential relationships are interesting ones. Do countries with a large share of their population residing in the capital city create an environment of economic rent seeking that siphons resources from the rest of the country into the capital via public spending and regulations that ultimately weaken aggregate economic performance? This is probably the question for a thesis in urban economics but why not have some fun with it. I took per capita GDP data in U.S. PPP$ for 30 OECD countries in 2007 along with an estimate of their population and used the 2008 World Almanac to find the population of each country’s capital. I calculated the share of population accounted for by the capital city and plotted it against the level of per capita GDP

The result? Well, there really was not much of any pattern. There were two obvious outliers –Iceland and Luxembourg – so I removed them – and plotted again with a trend line. The result in Figure 1 could not find a negative relationship between per capita GDP and the share of population residing in the national capital.

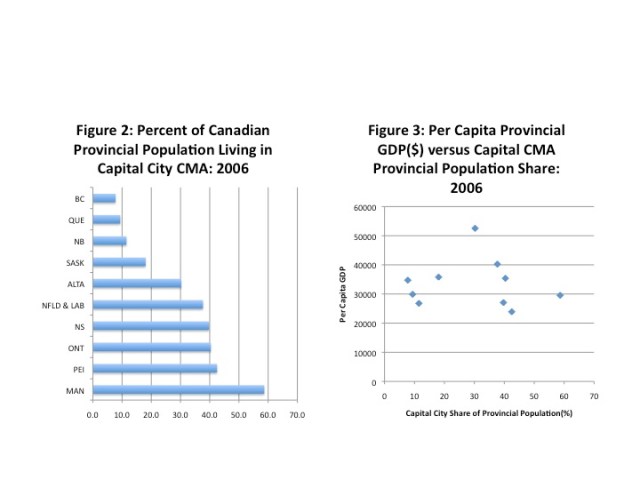

Does this mean there is no relationship? Well, this is pretty crude empirical analysis. A richer data set and some control variables would be helpful. The data set probably also needs to be expanded beyond the set of OECD countries, which are by and large relatively prosperous and stable countries. However, one final experiment. Canada’s provinces vary quite a bit in terms of the provincial population share accounted for by the capital city from a high of 59 percent in Manitoba to a low of 8 percent in British Columbia (Figure 2). When the capital city population shares are plotted against per capita GDP for the year 2006 you get what could be interpreted as a hump-shape – per capita GDP grows as the population share grows up to about 30 percent but then increases in the share are associated with a decline in per capita GDP (Figure 3).

This might suggest that a provincial capital that grows as a share of the province’s population has a positive impact on per capita GDP growth but once it reaches a critical point of about 30 percent of the population it starts to exert a negative effect. Perhaps once a third of the population lives in the capital, the critical mass exerts political dominance on provincial life out of proportion to its population size. The Canadian provinces that fall into this boat would be Newfoundland & Labrador, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island and Manitoba. However, there are only 10 data points here and only for one year. Get rid of Alberta (the peak point) and you are back down to a flat line relationship between the two variables. However, this might be an interesting topic for a graduate student to tackle.

In terms of a specific application, I am particularly curious if this type of story might explain why in Ontario over the last decade so many elementary and secondary schools have been closed outside of the Toronto area while the Toronto schools have not only managed to keep more small schools open but also maintained funding for things like swimming pools and teacher-librarians. Apparently, 19 percent of schools in Eastern Ontario and 10 percent of schools in northern Ontario have teacher librarians compared to 92 percent in the GTA schools. Did close proximity to the provincial decision makers create opportunities for advocacy not available outside the capital?

The % in the capital city could be low for two reasons. 1. the province/country has a rural population/agricultural economic base or 2. the capital is located in the province’s/country’s second or third city (e.g. Victoria, Regina,…). It would be interesting to try to differentiate between these two different explanations.

Liveo,

I think your analysis of figure 3 is incorrect. Surely the “hump shape” is defined by Alberta’s oil wealth and therefore not indicative of a trend. Take out Alberta and your scatterplot is trend-less. Because Newfoundland, Ontario NS and PEI have the same fraction in the provincial capital they can define am “error bar” (ie a 1-sigma deviation) and by eye it looks like a few thousand dollars. With that kind of fuzz I don’t see your conclusion.

Cheers,

Chris

Chris:

Thanks for pointing out that Alberta is the peak. I had attributed the peak to Newfoundland and Labrador which I have now corrected in the text of the post.

As for your observation that without the peak, the diagram is trendless, well, I know. I’m trying to be provocative and am fully aware that 10 data points is inadequate and in fact I say: “However, there are only 10 data points here and only for one year. Get rid of Alberta (the peak point) and you are back down to a flat line relationship between the two variables. However, this might be an interesting topic for a graduate student to tackle.” I think a rigorous empirical assessment would require a fairly substantial pooled-time series cross-section going back at least half a century if not longer.

Frances:

Differentiating the provinces that have a strong second city from those that do not is a good point. Saskatchewan and Alberta, for example, have strong second cities while Manitoba in particular and even British Columbia do not. Ontario is dominated by Toronto but also has the federal capital region and that needs to be considered. More data definitely required.

Livio, as you say, it seems you’d need to look at a weaker state or one subject to popular unrest to see if this relationship holds. I think Afghanistan, Pakistan or India might be interesting countries to analyze, for various reasons.

In Canada, the effect of proximity to the people in large capital cities might be offset by the under-representation of urban areas in our electoral system. One riding in Brampton, for instance, has nearly 200,000 residents, while the average is around 110,000.

At least in Canada I don’t think the causation would run Big Population in Cities -> Rent Seeking behavior. The relationship probably holds better in dictatorships or countries with weak governments.

For sure, check out Portugal. A unitary state with strong central government centred in the capital city Lisbon. If that isn’t a poster child for rent seeking activities by urban residents of the capital versus the rest of the population I don’t know what else is.

The claim to fame of the next largest city of Porto in northern Portugal is for its hard working and industrious citizens. That must tell you something.

CBBB: Look into the fairly recent book, “Soccernomics”, which touches on the relationship between economic rents and capital cities from a soccer perspective. Specifically, the past successes in the capital cities of (former) dictatorial countries (i.e. Spain, Portugal, Yugoslavia) and democracies (i.e. England, France, Germany) tend to differ, with the second/third cities performing much better in the democracies.

I’ve long had an interest in economic geography, economic history and urbanism. I cannot think of references off-hand, but I do recall that as countries urbanize and industrialize, the major city at first grows a lot more rapidly that other cities, but then in the later phases, the growth of the largest city slows down and secondary cities grow much faster.