This summer I went to a conference for behavioural economists and economic psychologists. The presentations were entertaining.

Did you know that when coffee is given a fair trade label, people say it tastes better, even if it's just regular coffee? And fair trade coffee, without the fair trade label, doesn't taste as good?*

Did you know that an increase in a co-worker's pay will cause a person to reduce her own work effort?**

But somehow the intellectual excitement wasn't there.

Then I met Pete Lunn, an economic psychologist, who articulated the cause for my disquiet.

Economics, he said, is basically a deductive discipline. Psychology, on the other hand, is inductive.

It's a caricature, a gross over-simplification. But it has an element of truth.

Economists like to begin with a general model, work out its implications, and then go to the data to test the theory. Yes, there are applied economists who spend their lives trying to find out facts about the world. But facts in and of themselves are uninteresting unless they illuminate economists' view of the world, and can be explained in economic language.

Psychologists begin by observing people's behaviour, looking for generalizable patterns. For example, if people are observed acting as if they are averse to losses, psychologists infer that loss aversion exists. Yes, psychologists have conceptual explanatory frameworks, such as prospect theory, to explain such phenomena,but these theories are not the elegant mathematical creations favoured by economists. And where is the status and prestige? Look at the psychology journal rankings. There isn't a top-ranked journal with "theory" in the title.

It's a dilemma for behavioural economists. Yes, it's possible to go into the lab or into the field, run experiments, and see how people actually behave. To do what economic psychologists do, in other words. But what do you do next?

My co-author and colleague David Long sets out some options in his research on the nature of interdisciplinarity.

One is the multidisciplinary approach: take some psychology, take some economics, and use whatever works to explain the behaviour at hand. It's intellectual parallel play – working side by side, but not really interacting.

The danger of multidiscplinary is sinking to the lowest common denominator: combining economists' knowledge of experimental methods with psychologists' understanding of economic theory. The upside potential is arriving at better understanding of real-world phenomena than any one discipline could achieve individually.

Yet multidisciplinarity is not a stable long-run academic equilibrium. Parallel play isn't as fun as working with colleagues who share a common intellectual understanding. So multidisciplinary projects tend to morph into other things…

One possibility is what David Long calls "transdisciplinarity" or, less charitably, academic imperialism. Transdisciplinarity takes the paradigmatic approach of one discipline, and applies it to another discipline's subject matter. Economic psychology, for example, applies the methods of psychology to economic choices. Not every paper in the Journal of Economic Psychology simply reports the results of some laboratory experiment, but a lot of them do.

These papers are unsatisfying for someone who thinks like an economist, that is, deductively, because the results aren't integrated within a coherent overarching model of human behaviour. But they're a profitable line of inquiry for psychologists – intellectually, because they allow for a broader application of psychological methods, and also literallly, because there is a strong demand for research that tell firms how to sell more stuff.

What about behavioural economics? Mullainathan and Thaler describe it as "the combination of economics and psychology that studies what happens in markets in which some of the agents display human limitations and complications." Those limitations are bounded rationality, bounded will-power, and bounded self-interest, or altruism. The behavioural economics research agenda, according to Mullainathan and Thaler, is "identifying the ways in which behavior differs from the standard model," and "showing how this behavior matters in economic contexts."

Behavioural economics differs from economic psychology in that it is typically conducted by economists rather than psychologists, and published in economics journals. But is behavioural economics just the application of psychological methods to economics, or is it something more? Does it really involve economic thinking?

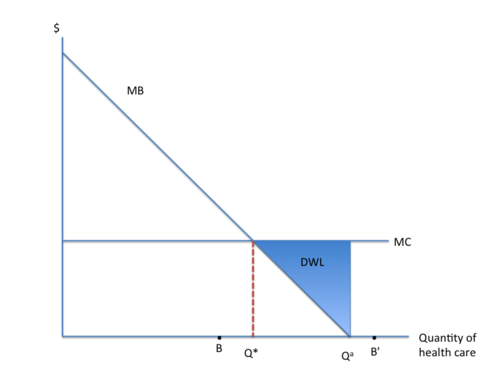

It might be easier to see what I'm getting at by looking at specific example, such as health care. The standard analysis of health care says that, if users do not have to pay the full marginal cost for their health care, they will demand excessive quantities of health care, and a deadweight loss will result:

In the diagram above, MB is the consumer's marginal benefit from health care services, which is assumed to reflect the actual benefit they receive from consuming health care, MC is the marginal cost to the insurer, society, or whoever pays in the end of providing the health care services. But the actual cost to the consumer, in this example, is zero. The optimal level of health care is Q*, where the marginal benefits of health services are just equal to the marginal costs. But because the consumer doesn't pay that full marginal cost, he or she actually demands excessive amounts of health care – health care for which the costs of provision are greater than the benefits – that is Qa. The consequence of this reckless overconsumption of health care is a misallocation of resources, shown as the deadweight loss (DWL) in the figure.

That's the standard analysis.

The problem is: people have no idea what the marginal benefits of health care actually are. So I'm sure that some behavioural economist could show that people's demand for health care was highly influenced by things like

- doctor's recommendations ("I'll see you in six months for another check-up") or

- the quantity of health care demanded by other people ("All my friends have had a complete body-scan, I'd better get one too") or

- awareness/salience ("Comedian David Mitchell has just been diagnosed with a fatal case of hurty elbow – my elbow has been feeling funny lately, I'd better get it checked out.")

O.k., so how does this get incorporated into the diagram above? Suppose that by manipulating framing, salience, or options, behavioural economists can cause people's demand for health care to go from Qa to some other point like B or B'?

Economists' policy recommendations – our ideas about which policies enhance economic efficiency and which ones detract from efficiency – are all based on the idea that individuals know what's best for themselves. That we can draw demand functions and use them to infer the marginal benefits to consumers of goods and services.

But if people's demands are just a product of framing, salience, and the public prominence of hurty-elbow syndrome, how can we use them to infer the marginal benefits to consumers of consuming health care? How can we make statements like 'the marginal benefits of health care are less than the marginal costs'? How can we make any inferences about the efficiency of different modes of health care provision?

The economic approach to policy analysis is deductive - economists begin with assumptions about consumers' and firms' preferences and behaviour, and these assumptions allow us to say things like 'insurance leads to excess consumption of health care services.' (Or 'firms will pass through savings from the elimination of PST on inputs to their consumers.')

Perhaps there is some way of including behavioural considerations into that framework. Perhaps we can say "the consumer's demand is really what is shown by MB, he just chooses to consume B because he is ill informed – but the happy thing is that, in this circumstances, there is no inefficiency resulting from the provision of insurance."

But that doesn't feel right to me – if a consumer's marginal benefit from consumption is something other than what is revealed by his or her demand I could just make up anything as a marginal benefit curve, and economics would become a completely ad hoc exercise.

Dabbling in economic psychology or behavioural economics is a little like taking the red pill – you go down the rabbit hole, and wake up realizing that the entire world is an illusion.

How can economists evaluate policy if they can't use people's preferences as revealed by their choices? We still need some way of figuring out which policies help people and which policies hurt people.

For example, opt-out policies have much higher take-up rates than opt-in policies. But in picking between and opt-out and opt-in policy, we still need to know in an ideal world, would we want a high take-up rate or a low-take-up rate? Causing people to opt-out rather than opt-into savings plans makes them save more – but if that causes excessive reductions in current consumption that might be a bad thing.

Once you fall down the rabbit hole, you just have to keep on going. If people's choices are not a reliable guide to their well-being, you have to turn to something else. Ask people how happy they are and measure well-being in terms of happiness. Evaluate health care spending by looking at objective measures of health, such as mortality, morbidity, or survival rates. Chuck out the entire elegant theoretical framework of welfare economics.

That idea has me, for one, reaching for the blue pill – after all, people aren't stupid, so standard economic analysis isn't a bad approximation of the real world, is it?

But I can't find one. I can't get all of that behavioural stuff outside of my head.

I want a purple pill – a merging of the red and the blue – that would allow me to merge behavioural insights into a coherent model of economic behaviour.

(Evolutionary economics – and other research programs that explain why humans behave the way they do – might have some promise as a purple pill).

But I don't know if such a thing is even possible.

* Christandl, F., Lotz, S., & Fetchenhauer, D. (2011). The Taste for Fairness – How Ethical Labeling of Consumer Goods Shapes People's Taste Experience. Talk. IAREP/SABE/ICABEEP Conference, July, 13th – 15th, 2011, Exeter (UK).

**Bracha, Anat; Gneezy, Uri; Loewenstein, George (2011) "Relative Pay and Labour Supply"

Joshua: “I would hope that most people see that the very notion of an optimal amount of tennis to play that doesn’t put the individual’s preferences at the center of it all is strange, maybe even disturbing.”

Frankly, I find the notion of an optimal amount of tennis to play rather strange. 😉

You can make assumptions that will let you define and find an optimal amount of tennis to play, but then it is contingent upon those assumptions.

Frances – blush. At least I have provided some supporting evidence for my doubts about my own intelligence and rationality. 🙂

Tracy W.: ” the more we believe the scientists’ evidence that we make decisions irrationally, the more we should be very doubtful about said evidence.”

One problem is that the argument is too coarse grained. Scientists do not simply show that people are irrational. They show how they are irrational. Furthermore, to show that people are irrational, the scientists have to show what is rational, and that means that the scientists and their audience have to be rational. There is no circularity.

Frances Woolley:”What’s odd, though, if that if you get 10 or 15 economists together for dinner at some conference, hand around the total bill and ask everybody to pitch in, there will almost always be a large surplus. So does that mean we don’t free ride, or that we’re more concerned about status, waiting until everyone is watching and then throwing in a $50 or a pile of $20s, than about free riding?”

I noticed a similar phenomenon with a different group some years ago, when I put the dinner bill on my credit card. I don’t think that status was a factor, because nobody was looking at what other people were paying, or at how much others’ dinner had cost. I pointed out that we had too much money, but nobody asked for any back. So I left a huge tip. 😉

I have also noticed that some groups are quite precise about what their own dinner cost, and how much they want to contribute to the tip. Other groups avoid a surplus, but have a norm of equal shares.

Bork – apology retracted. I’ve just spent some time reading through a few papers in Personality and Social Psychology Review, which you describe as an “exclusively theory” journal. Those papers are still very empirically grounded, very inductive – not at all like the “let’s take a set of assumptions and see what we can derive from them” deductive papers that you find in econ theory.

The better example, though, is what is taught in intro courses. Which does each course begin with? Econ 1000 begins with basic models, and psyc 1000?

Peter: “One of the brain teasers I struggle with is why do only business students cheat at Prisoner’s Dillema? Everybody else cooperates and achieves the group optimal result – the commerce, econ, & MBA students cheat (or act in their “own” best interest depending on your perspective) and ruin it for everybody. So who is making the “bad” decision – and why?”

As I recall, the commerce, econ, and MBA students have been taught to cheat. Naive students tend to cooperate in classroom experiments. (Yes, they are cooperating with strangers, but with people that they can identify with.) Now, evolution, biological or social, may explain the tendency to cooperate, but there is also a rational argument, which Kant might have used. Because of the symmetry of the payoffs, if there is a correct strategy, it is the same for each “prisoner”. Among the symmetrical strategies, cooperation is best.

The analytical problem lies in reasoning by cases. Reasoning by cases nearly always works, and seems to be so obviously rational. But it may fail when there are interactive effects. The analysis of each case assumes that you can hold everything else constant, which may not be true. Reasoning by cases also fails with quantum mechanics.

Pete Lunn sent these thoughtful comments via email:

An additional thought for you:

Nudge is a decent attempt at a purple pill. It effectively combines the two approaches (BE and welfare economics) by identifying situations where welfare analysis remains possible but behavioural economics helps to move people towards optimality. The kinds of scenarios are: we designate people’s long-term preferences as their true preferences (policy to assist people to save, not overeat, etc.), the optimisation problem is too complex for them to solve (choosing a care plan or a portfolio), or the social optimum is non-controversial (policy to price in externalities like pollution). The regularities uncovered by behavioural economics help us to nudge people towards behaving according to their true preferences, solving complex optimisations, or pricing in externalities for little cost. But behind all of this is standard welfare economics and the goal is still to behave optimally according to standard theory.

This is all very clever and Nudge is consequently having a big impact. BUT, as you rightly point out, once you accept the behavioural findings, it is far from clear that we can define people’s true preferences or reduce situations to the pursuit of non-controversial optima. Hence, the applicability of Nudge-type solutions is probably rather limited, ironically enough by the findings of behavioural economics.

Pete Lunn.

“… that the more we believe the scientists’ evidence that we make decisions irrationally, the more we should be very doubtful about said evidence”

I don’t think that evidence of irrationality deserves special skepticism above and beyond what one ought to apply to all evidence of any kind.

I get the sense that you are worried about policy prescriptions to force people to be ‘rational’. Fair enough. But we still live in a democracy. In principle, I see no reason why it would be illegitimate for people to choose to implement policies that force them to be ‘rational’ knowing that they just won’t be able to resist the cookies in the clear container.

Frances Woolley: “Economics, [Pete Lunn] said, is basically a deductive discipline. Psychology, on the other hand, is inductive.

“It’s a caricature, a gross over-simplification. But it has an element of truth.”

Induction is making a comeback. 😉 Largely, perhaps, because machine learning has demonstrated its efficacy. To call psychology inductive 50 years ago would, I think, have been heresy. The hypothetico-deductive method reigned supreme.

Here is another caricature, with perhaps some truthiness. Economics is scholastic, psychology is empirical. (At least, scientific psychology is empirical. ;))

Now, I have read enough to know that economics is not scholasticism, but it still seems weak in empiricism. For instance, take Ricardian Equivalence.

Perhaps I am missing something, but here is the argument, as I understand it. Gov’t stimulus will not work because present deficit spending must be paid for by future taxes. Therefore, rational economic actors will not spend the stimulus money but will save it in order to pay those future taxes (or for their descendants to do so), thus defeating the stimulus.

Why is that argument not laughed out of court? First, when have gov’ts paid off their debt instead of rolling it over? (I have heard that Adam Smith pointed that out.) Andrew Jackson did so in 1835, but that may have been a mistake. Where is the necessity to save against future taxes? Second, even if rational actors would save against future taxes if they could, they have to be able to afford do so. Why then, is this an argument against a stimulus per se, instead of an argument for a stimulus targeted at poor people, who would not be able to save the stimulus money, or who would not expect much in the way of future taxes? The Ricardian Equivalence argument seems to fail what Freud called reality testing. (OC, there are other counter-arguments, but they accord the argument more respect. Why does it get any respect at all?)

@Ken Schulz, Sept 2, 2:03 a.m. (get some sleep, people!):

I would classify it as a failure in that it did not yield a result that the designers strongly believed would happen, but you are certainly that it revealed information (though I wouldn’t qualify as “new” the revelation that people over-consume health care).

I haven’t read Nudge, but I have read the UK Govt’s report on introducing nudgism into health policy. I get the point that there may be empirical evidence to support the effectiveness, but so what?

What disturbs me about this is that all the nudge policies are aimed at reducing the presumed costs to the government of various individual behaviors. The UK, like Canada, is stuck with a bloated, inefficient health care system that redistributes the cost of treating illness across the population, in addition to similar policies for the economic burden of illness…and as a result residents of the UK now have to put up with more intrusive policies? Looking at this report, I think the nudge enthusiasts are like David Suzuki: they don’t know what an externality is. Pollution is an externality. Joint pain and shortness of breath because you are obese and smoke are not externalities; they are your problem, and you can do something about them. Socializing the cost of treating those problems does not convert them into externalities.

I get that there may be much theoretical value to the whole behavioral economics discipline. What I distrust is the explosion of elite enthusiasm there has been for a very new idea. I think it’s great if policies can be designed and publicly sold as experiments, but I don’t think that’s the case with BE-based policies.

Min: Ricardian equivalence is a bad example because it’s been critiqued to death by economists (see wiki page on RE). Also RE doesn’t depend on government completely paying off debt as increased debt means bigger interest payments (irrespective of whether govt. plans to rollover or pay off) which is paid off through bigger taxes.

More generally, based on your last comment, I think you underestimate economists ability to critique themselves. As already alluded to by some comments economists can be pretty harsh on their own colleagues. I’m also not sure how you can say economics is weak empirically. I agree if you mean economics is weak in using experiments but weak empirically relative to what and by what measure?

Totally ignorant comment here, but nevertheless….

I thought the idea of universal health care was over basic health care. By that I mean you go to doc periodically for a check up. Don’t pass check up go to next step in, it is hoped, eventual remedy. And so forth.

Where in this sequence is there an ability to consume without limit? If you demand an additional check up and you’re found to be OK, you pay for that check up. If you don’t pass the check up and need to go to next step, it’s paid for under universal health care. If a MD has an unusually high check up frequency per patient, it’s a red flag and regulators will give that doc a check up.

The key here is you are discouraged from using unnecessary health care, and docs are discouraged from providing unnecessary health care. It’s not perfect of course and subject to abuse just like everything else in God’s world. But the assumption that everyone will demand health care services without limit seems sketchy.

Min: “Furthermore, to show that people are irrational, the scientists have to show what is rational, and that means that the scientists and their audience have to be rational. ”

No, all the scientists have to do is to convince themselves, and their audience, that they have shown what is rational.

Patrick: I agree with you that evidence of irrationality doesn’t deserve any special skepticism. And in fact, my problems come from the fact that I am inclined to accept it as being right (and, on top of that, my inability to think of any compelling reason why said evidence should not be applied to itself). If I thought that the scientists just had gotten this research wrong, like homeopathists, I at least would be saved these doubts about my own rationality.

I agree with you that there’s no problem in principle why it would be illegitimate for people to chose to implement policies that force them to be ‘rational’, such as Frances Woolley putting cookies in the opaque container. Where I do see the illegitimacy is in deciding to implement policies for other people to force them to be ‘rational’, as the people doing the forcing are apparently as likely to be irrational as the people being forced.

Tracy W: “you have the right to decide for your son because you’re his parent. But he’s going to turn 18, and then I understand that as a matter of law you lose that right.”

I didn’t say he wasn’t free to buy the sneakers with his own money. And I’ll admit, the principal stupidity is not the purchase of the sneakers. It’s the recognition of trademarks as property which rigs the game in favour of a market failure (80% gross margin). It’s a prisoner’s dilemma in that we would all be much better off if no one bought swooshes, but then there’d be big individual gains from defaulting. Once we permit the game to be played (by enforcing trademarks), then it could possibly be rational behaviour. But it is collective stupidity.

“how can I decide whether a pyschologist, or any other ‘ist, is smarter than me, and thus competent to decide such matters for me, or for other people?”

You don’t have to. You just have to understand how the market place scientific ideas operates. The case for an inefficient competitive equilibrium in academic research (unlike the case for the market for swooshes) is pretty hard to make. The principal consumers of that research are other academics, who generally

1) are extremely well informed and

2) have a strong economic interest in contesting and disproving the published results of others (that’s how careers are made).

The more significant and loudly proclaimed the result, the faster and more thoroughly it will be challenged and (if necessary) debunked (c.f. cold fusion).

If you think that a believing in science is equivalent to accepting any random idea on authority, I don’t think you have thought about how science functions. Mistakes, and even deliberate falsehoods, can occur but they cannot be sustained. This is clearly not the case for swooshes.

beezer: “Where in this sequence is there an ability to consume without limit?”

There isn’t. Frances’ claim (as I see it) is that if you were given your current health care consumption as a cash grant instead, you’d consume less healthcare and allocate more elsewhere because the marginal cost of healthcare consumption is no longer zero. I think it’s uncontroversial.

“beezer: ‘Where in this sequence is there an ability to consume without limit?’

“K: There isn’t”

There kind of is (K, I realize you are referring to a model, whereas I am referring to behavior under certain policy conditions). Of course consumption is not truly limitless, but for services that are not strictly subject to gate-keeping and full-on rationing, it is quite easy to consume far beyond your marginal medically-necessary benefit, if you exclude from “benefit” the utility of things like consolation, getting attention, and the signalling value of certain types of consumption (i.e., “I’m in therapy.”). You can’t get a liver transplant just because you feel like, but you can get (on the public dime) many times the cost of a transplant in outpatient services that offer you no benefit. Even in your country, beezer (I assume from your blog that you’re in the US), consumption with high DWL is very common.

So, in a situation of such gross inefficiency (e.g., excess profits, bloated wages and fees, consumer time wasted on needless consumption), one would hope that BE offered us something…but I think it does not. On the other hand, I’m not a full-on economist and there are nuances about Frances’s post that are beyond me.

“Where I do see the illegitimacy is in deciding to implement policies for other people to force them to be ‘rational'”

To what extent is this sort of objections based on fear of the prospect of being forced to not do things you’d rather continue doing?

Trite example: very few people complain about speed limits being oppressive because speeding imposes all sorts of negative consequences on people other than the speeder. What about overeating, or not exercising, or smoking in a country with publicly funded health care? Someone else’s irrational preferences costs the rest of us money. So who wins? Do we dump universal tax funded health care, or does the state use its power to coerce people to behave differently?

I think it’s perfectly legitimate to democratically decide that, in return for the benefit of public health care, people give-up some freedom and have some responsibility imposed on them. Of course, people might choose the opposite and though I’d disagree with the choice, it’s still legitimate.

DavidN: “More generally, based on your last comment, I think you underestimate economists ability to critique themselves.”

Perhaps so. I usually say that I am referring to public discourse, but omitted to say that this time.

DavinN: “As already alluded to by some comments economists can be pretty harsh on their own colleagues.”

What surprised me about Ricardian Equivalence was first, that the argument was entertained, and second, the lack of public debunking. As I recall, DeLong made an argument along the lines that only part of the current stimulus had to be saved for future taxes, but did not make any empirical refutation. His is one of the counter-arguments that I had in mind as showing some respect for RE.

It is not whether economists argue or fight with each other, but the apparent lack of empiricism that I was commenting on.

I’m coming in a bit late here, but I’d like to say this has brought me to a new realization.

I’ve been suspicious, if not downright disbelieving, of the assumptions typically made in economics for some time. But Frances Woolley has brought home to me a whole other dimension of the problem.

That is, I’ve generally taken the position that if economists are working from false assumptions (perfect information, false ideas about human psychology/behaviour, decreasing returns to scale, basing theory on “utility” but then acting as if dollars make an adequate proxy for “utility”, etc.) then they will be wrong about the kinds of policies that will give us an optimum economy, and an alternative theory that had correct assumptions would give us correct answers.

But the problem is rather that if you conclude people’s preferences are in various ways not perfect, you cannot use them as the basis for what makes an economy optimum. The whole question of what makes a “good” economy in the first place becomes open.

That seems like a big problem. In a way it is, but only because economics has for a few decades now suffered from wanting to be physics (and 19th century deterministic no-chaos, no-quantum physics at that), which it isn’t and cannot be any more than, say, anthropology can be. Once you step back from the idea that the optimum economy is determined by people’s preferences taken as a given, which is circular, tautological, and ignores various processes by which preferences are formed and changed–once you abandon that, you are left where we used to be: Realizing that the question of what kind of economy would be best is a political one.

(It can be argued that one reason economics ended up like this is precisely an attempt to dress up one political consensus as scientific and inevitable)

Time to stop calling it “economics” and go back to calling it “political economy”.

Secondarily, I would think that economics can still determine things without making claims about what’s best. That is, if you use real-world assumptions rather than false ones you can with some accuracy describe the kinds of economic results that would result from different policies, including ones that manipulate preferences, and compare and contrast these results, while trying in somewhat the manner of an ethnographer not to prejudge which sort of result a social/political process ought to be choosing, since that’s really up to people.

There are experiments at the edges — even Darwin conducted experiments on some of the sub-processes, i.e. the transport of seeds and roots across the ocean.

But note well, this stuff is adaptation — only one part of the explanatory mechanism — it is not speciation, made thing explained by Darwin.

Someone wrote,

“Greg Ransom, there are experiments in evolutionary biology. Principally drosophilia, but also nematodes and even Russian silver foxes.”

Mankiw defines ‘economics’: the study of how society manages its scarce resources.

Is economics the study of the tradeoffs people face in managing resources or the decisions people make when confronted by these tradeoffs? The latter to me seems to be a historical/psychological (empirical) question, whereas the former seems to me to be a logical (deductive) question. The difficult truth, I think, is that Mankiw is right and economics deals with both: to understand how resources are managed is both a logical and historical/psychological question.

Purple Library Guy,

If it’s inappropriate for economists to ape physicists, then why is it a problem that they have (in many cases) been aping 19th century physicists rather than 20th/21rst century physicists? Philip Mirkowski has been wrestling with that problem for decades. He is not yet the victor.

The key fact in all this is that justifications and explanations end somewhere, and the 19th century philosopher’s categories of “induction” and “deduction” do not capture these end points, as Wittgenstein, Popper, Hayek, Kuhn and others showed us decades ago.

What is a “modern” economist?

An academic following the defunct dictates of some 19th century philosopher …

Let’s put a big red bow on this central point:

The procedures of “induction” and “deduction” fail to characterize or capture the nature of empirical science, most especially complex causal explanatory sciences like Darwinian biology.

The procedures of “induction” and “deduction” as applied to “science” were dictates invented by philosophers — like Carnap and Mill — and the great result of work over the last 100 years is to completely reject that picture of “science” and knowledge, e.g. see the work of Kuhn, Wittgenstein, Hayek, Popper, etc., etc.

When will tenured economists be told the news …

Ironically, economist Carl Menger was one of the first to get some of the central points against the “induction” and “deduction” picture later made by Popper, Hayek, and even Wittgenstein and Kuhn.

But economists don’t know anything of this work.

Found it. I remember coming across a blog post on behavioural economics, but couldn’t remember where. It’s here, by Jeff Smith:

I am of several minds (pun fully intended) about behavioral economics. First, the name irritates me; all economics is properly about behavior. Second, I think some of theoretical work that transpires under the heading of behavioral economics, such as the development of new choice axioms, is largely wheel-spinning. Third, I think that in some quarters behavioral economics has induced a sort of looseness of thought. Instead of thinking very hard about a phenomenon in order to come up with a non-obvious rational choice explanation, someone simply blurts out “framing” or “hyperbolic discounting” and the thinking stops there. Fourth, it irritates me when people equate rational behavior with an assumption of costless information processing. It seems to me that the correct way to proceed is to incorporate a cognitive budget constraint into the optimization problem. It is hardly rational to spend huge amounts of costly cognitive resources to solve some problem when a quick, cheap but slightly wrong heuristic is available Our models should reflect this and, more broadly, we should not treat clearly irrational behavior as the benchmark of rationality. This requires learning a bit of psychology and/or neuroscience in order to get the budget constraint right. Fifth, I think that people who dismiss the entire behavioral economic enterprise (“wackonomics”) based on the failings of some of its practitioners are being careless and making a serious mistake. There is important, policy relevant behavior to be explained that does not fit will with traditional models that assume costless information processing. I think economists have much to add in coming up with new and useful explanations of these behaviors.

Mr. Gordon, this bit of your quotation from Mr. Smith strikes me as odd:

“Third, I think that in some quarters behavioral economics has induced a sort of looseness of thought. Instead of thinking very hard about a phenomenon in order to come up with a non-obvious rational choice explanation . . . ”

As far as I know, the “rational choice” axiom was never first a hypothesis. It was never tested, never adopted because of some solid reason to believe it was true. Rather, it was used because it seemed reasonable to someone at the time and because it made the math easier. I find it hard to see where “thinking very hard” to come up with ways to salvage the rational choice “explanation” for any given situation represents non-looseness of thought. If there were some reason to prefer the rational choice explanation to any other (beyond convenience and tradition), then readily abandoning it might represent “looseness of thought”, but as far as I know there is no such reason.

Purple Library Guy: “I find it hard to see where “thinking very hard” to come up with ways to salvage the rational choice “explanation” for any given situation represents non-looseness of thought.”

Once, in physics lab, an experiment seemed to violate Ohm’s Law. As part of our homework we were asked to explain why it did not. My explanation was to rewrite Ohm’s Law. 😉 Needless to say, my explanation gave no physical insight. I thought that it was clever, but I think that Smith could call it looseness of thought.

If rational choice is the default assumption, even though it will at times be violated, then seeking to preserve it if possible is parsimonious and desirable. To shrug your shoulders and say, oh, well, here is another case where it is violated weakens the theory.

OTOH, psychologists have good reason to believe that most humans are capable of only limited rationality. If that is your starting point, then to assume a violation of rationality that is predictable is not looseness of thought, but adherence to a different theory.

Min: ‘What surprised me about Ricardian Equivalence was first, that the argument was entertained, and second, the lack of public debunking. As I recall, DeLong made an argument along the lines that only part of the current stimulus had to be saved for future taxes, but did not make any empirical refutation. His is one of the counter-arguments that I had in mind as showing some respect for RE.’

With respect I don’t think the economics blogosphere (probably more apt to call it the politics blogosphere) is representative of the wider academic economics community and personally I think it’s a terrible sample to make generalisations about the wider discipline from. With respect to empiricism within the economics I think it would be hard to mount a case that it’s weak. Anecdotally at least, I find it’s dominant if not dominates the discipline.

Um, yes. Ricardian equivalence has been put through the academic wringer. The basic point is correct, but the conditions required to get pure Ricardian equivalence don’t hold.

Purple Library Guy: Positive economics doesn’t tell us what is ‘optimal’ per se. Positive economics can tell us what is Pareto optimal, what’s a stable and unique equilibrium, which equilibrium minimise dead weight loss etc. but it’s politicians and economists who enter the political fray who weigh the competing results and then according to their own values use economic theory as rhetoric to fit their political narrative which ultimately is not science but value judgements so I think your criticising of economists proclaiming policies which are ‘optimal’ is better directed at politicians and economists who practice politics than the discipline per se.

Also I think you need to make a more substantive set of arguments on why you find rational choice theory or other assumptions are false and unrealistic and therefore the results that flow are wrong. How do you judge whether an assumption is good or bad, and realistic or not?

DavidN – Just to get this straight, are you arguing that the statement “this equilibrium minimizes the deadweight loss” is a purely positive statement?

As an outsider let me say that BE is really fun to read. And not just because Ariely writes well – it doesn’t hurt, but that is not all. BE helps me use my rational brain to make decisions based on my irrationality.

I save at a higher rate using the account my financial advisor set up that I can’t access without asking his admin for help. I can cheat and dip in but I don’t because it’s hard. The savings account linked on my RBC website was useless. I could too easily “borrow” from my savings.

There are phenomena that need to be understood and policies shaped around them. I do not like to be coercive but it makes sense to me that 401Ks in the US be put by default into a mixed account with equities and bonds instead of a savings account. Let people choose, but choose the default sensibly.

Driver’s licenses should come with a default organ donation.

Many small purchases over time tend to bring more satisfaction than a big one.

It seems to me that BE is trying to understand how individuals really are, rather than how they should be.

But BE is not going to tell me that there is a serious aggregate demand problem or what to do about debts or what to do with credit default swaps or why the merger of AOL and Time Warner was a disaster.

Frances: I think it is if you use it as a description but not if you use it as a criteria of what is ‘optimal’ (in the non-techical sense) which then in my opinion it becomes political rhetoric. It might be semantic but I think it’s an important distinction.

Chris J “As an outsider let me say that BE is really fun to read”

And as an insider, too. As Pete Lunn said in that comment I quoted earlier, Nudges might be as close as we’re likely to get to a purple pill, that incorporates the insights of behavioural econ and still keeps the power of more conventional econ.

I use those BE things, too – hiding cookies from myself etc. But I do think it is much more challenging of the mainstream econ paradigm than some might like to think.

DavidN – so economists get up, tell their students “free trade is Pareto optimal” or “free trade is optimal” (because it’s tedious to keep on saying Pareto) this shouldn’t be taken to mean to mean that we’re advocating free trade?

Frances: Depends on the context. Students first encounter ‘free trade is optimal’ in econ 101 and I think that is a problem because, just anecdotally, I don’t think students at that level are equipped to make the subtle distinction between ‘free trade is Pareto optimal’ and ‘because free trade is Pareto optimal we should have free trade’ so in that context yes I think economists are advocating for free trade (even if it might not be deliberate or conscious). If lecturers noted explicitly that ‘free trade is Pareto optimal’ is different from ‘free trade is Pareto and therefore we should have free trade’ and students can grasp the difference then no I don’t think it is advocacy.

I’m generalising but my personal opinion is econ 101 curriculum is to simplistic and not critical enough. I understand there are constraints to teaching more sophisticated material due to student’s ability at that level, but anecdotally at least, I feel students come out of econ 101 thinking that economists think free trade is good, perfect competition good, monopoly bad, regulation is bad, taxes are bad, union are bad etc. etc. when really just because something is ‘Pareto optimal’ it doesn’t follow that you should support it normatively.

I’m generalising again, but I think when outsiders look at economists advocating normative positions they can’t distinguish it from positive economics and therefore it leads them to believe economics as an discipline is inherently ideological which might not or might not be problem but is something that annoys me.

Just to clarify some points.

I think positive economics = science, normative economics = politics. For example suppose you have an economist with an utility function, u(x,y). x denotes Pareto optimal policies which are enacted and y denotes the disutility to family and friends from enacting those Pareto optimal policies, e.g. the economist comes from family and friends who all work in the textiles industry and this industry would be destroyed if there is free trade.

Positive economics may tell us which policy is Pareto optimal but it can’t tell us whether the economists should support that policy. Whether the economist supports that policy depends on their values i.e. their utility function. So going back to my original response to Purple Library Guy, positive economics or economics as an academic discipline doesn’t support any policy as ‘optimal’ per se. When economists do support policies they are making normative choices.

Someone above quoted Mankiw: “Mankiw defines ‘economics’: the study of how society manages its scarce resources.”

A quibble here. There’s no intrinsic reason for capital to be scarce.

“The owner of capital can obtain interest because capital is scarce, just as the owner of land can obtain rent because land is scarce. But whilst there may be intrinsic reasons for the scarcity of land, there are no intrinsic reasons for the scarcity of capital.” Keynes, concluding notes to the General Theory.

Human behaviour and psychology, far more frequently than admitted in economics, totally drive real world events. There should be a mathematical formula for hubris.

Beezer,

But, as Keynes tacitly acknowledges in that very paragraph, that line is mistaken: “Even so, it will still be possible for communal saving through the agency of the state to be maintained at a level which will allows the growth of capital up to a point where it ceases to be scarce” i.e. savings and capital are scarce because the returns on savings and capital are scarce. Hence the abundance of capital that Keynes proposes can be obtained only at the cost of using the threat of physical force against the public, which leads me to think that (only any reasonable interpretation of ‘intrinsic’) it is the creation of an abundance of capital which is artificial, not the scarcity of capital. We can see this empirically by the failure of banks in the post-WWII era to maintain low rates of interest without resorting to totalitarian means e.g. in the failure of the Dalton experiment in the United Kingdom. So Mankiw is still right: economics is the study of how society manages scarce resource, including the theory of capital.

(Of course, that section of General Theory are famously one of the weakest.)

(One could add that the absence of scarcity in capital would be a state where the value of capital is zero or negative, either because it costs nothing to produce or because capital cannot reduce the costs of production or because of an absence of scarcity in consumer goods. None of these states of affairs are possible, since the creation of capital always makes other capital obsolete via technological progress and thereby increases the scarcity of capital. Keynes’s mistake, I assume, is the old one of homogenising the heterogenous i.e. regarding the creation of capital as an addition to an effectively uniform stock.)

K: Maybe 5, 10 years ago, I would have thought like you, and defended the social sciences that way. But I’ve been reading more and more results of scientists’ research into people’s irrationality, and now I have my doubts. How do I know that the principal consumers of that research have that strong incentive to disprove it, am I possibly being subject to availability bias? Do I value the opinions of scientists and skeptics above those of creationists, aromatherapists and philosophers because the arguments are better, or because I’ve chosen to identify with those groups for non-rational reasons?

And note, particularly, we’re talking about the social sciences here. Cold fusion belongs to the hard sciences – where often engineers can and will try to build something using that principle. A really good reason for thinking that evolution can work is that engineers use evolutionary algorithms. With the social sciences, it’s harder to think of places where attempts to use the information in social engineering produce results that are clearly incompatible with the theory. Government programmes typically are implemented, have different results than expected, which the opponents proclaim as clear evidence of the failure of the programme, and the proponents say merely shows that the programme wasn’t implemented right. One can still come across people who argue that a centrally-planned economy could work, what the collapse of Communism merely showed was the collapse of that particular system.

“If you think that a believing in science is equivalent to accepting any random idea on authority, I don’t think you have thought about how science functions.”

I don’t even know what you mean by “believing in science”, so I am unable to apply this idea to myself. I can believe in some scientific results, the Laws of Thermodynamics I believe in. I can believe that the process of science is better as a way of finding things out than any other way I know about (at least when mathematics cannot be applied). But I don’t know whether this adds up to “believing in science”, I certainly don’t believe in every result that is claimed to be scientific, and indeed I think that such an attitude would be the opposite of scientific. However, as I said in my reply to Patrick, my problems with the research into irrationality come from my being inclined to accept those particular scientific results. If you have some good reasons why this research is wrong, I would be delighted to hear them.

Patrick: “To what extent is this sort of objections based on fear of the prospect of being forced to not do things you’d rather continue doing?”

If by “you’d” you mean the plural “you”, I think to a very large extent.

“Someone else’s irrational preferences costs the rest of us money. So who wins? Do we dump universal tax funded health care, or does the state use its power to coerce people to behave differently?”

If we had a rational government, then the logical answer would be the government. But we don’t have rational government, what you don’t mention in your analysis is that the state is made up of people. If people have irrational preferences in their own lives, I can think of no reason why they will suddenly be rational when running a government, or passing laws. (And we also know that even with perfectly rational voters, voting can produce irrational results). So we should expect a state to use its power to coerce people to behave irrationally form time to time, and indeed I can think of a lot of examples in history of them doing so (for a start, getting into a war was always a bad decision for the side that lost, sometimes arguably for both sides, and there have been a lot of wars).

I am reasonably confident that some laws do make society better off than total anarchy. But on the other hand, we know in the past that governments have passed and enforced laws, such as those requiring religious conformity, or male patriarchy, or banning homosexual acts, on the basis that such laws were necessary for society to function, but our modern societies are happily getting along with a lot more freedom in those areas. So governments can be wrong about whether a particular set of laws are necessary.

In terms of universal tax-funded healthcare, someone’s rational preferences might also cost us a lot of money. For example, my brother (a non-smoker) was out cycling when a van turned right in front of him, leading to him getting a severe brain injury and costing the NZ government somewhere likely in the 100,000s of dollars range. He was wearing a helmet, and the doctors thought that without it he would have died, which, to be cold-hearted about it, would have been a lot cheaper for the NZ government. Was his decision to wear a helmet though, irrational, from his point of view? How about his decision to go road cycling rather than staying in the safety of a gym? How about his decision to enter a cycling road race which probably influenced his decision to be on the road rather than in a gym?

“I think it’s perfectly legitimate to democratically decide that, in return for the benefit of public health care, people give-up some freedom and have some responsibility imposed on them. ”

I would prefer for it to be rather illegitimate, as the potential loss of freedom in return for public health care strikes me as unending. What human behaviours don’t have an influence on health? Speech can hurt people mentally, requiring mental health services and thus public expenditure, and quite arguably speech has contributed to some people with good persuasive skills getting into positions of power beyond their competence (as a Kiwi, my example is Winston Peters, you can probably think of a politician from your own country), so by your principle it would be legitimate to restrict freedom of speech. Freedom of religion – some religious practices impose health care costs (how many people are hit by cars while travelling to church?), so it would be legitimate to restrict that. Freedom of association – battered spouses do often require hospital care, so the state should be able to make decisions about who gets to associate with who.

Of course, I believe in freedom of speech, so I think you should be able to make some arguments in favour of restricting anything. But overall I’d prefer to live in a country where the constitution (be that written and/or in people’s hearts) was such as to require a very high level of consensus to pass such laws, and to keep them on the books). I’d rather pay higher taxes for publicly-funded healthcare than give up on freedom whenever someone comes up with a plausible-sounding argument that exercising a freedom increases healthcare. Especially given all the evidence that we’re likely to be making irrational choices ourselves.

Tracy: “I would prefer for it to be rather illegitimate, as the potential loss of freedom in return for public health care strikes me as unending. What human behaviours don’t have an influence on health? Speech can hurt people mentally, requiring mental health services and thus public expenditure, and quite arguably speech has contributed to some people with good persuasive skills getting into positions of power beyond their competence”

A-effing-men, every word of it.

Tracy, by you’d I mean the contraction of ‘you would’.

I don’t buy the slippery slope argument. Nobody is proposing that we eliminate democracy. Your argument really just seems to boil down to wanting to rig democracy to favour your preferences.

And by democracy, I mean as it currently exists in Canada – parliament, the charter, the courts etc …

Patrick: You are of course free not to buy the slippery slope argument. As I have said, I believe in freedom of speech. However, in this case I think the slippery slope argument is valid, in my own lifetime I’ve seen the taxation of dietary fat move from being a reductio ad absurdum to being an apparently serious policy proposal. I’ve heard health professionals recommend laws restricting freedom of speech about medical research. I know that democratic countries have laws banning holocaust denial, or vice-versa calling the killings of Armenians in the 1920s a genocide. The truth or otherwise of an argument is independent of whether you agree with it or not, millions of people “don’t buy” evolution, but that doesn’t mean that the law of evolution is false. (Note, I am not claiming that my slippery slope argument here is as well supported as the law of evolution, just that the fact that someone says that they “don’t buy” an argument doesn’t necessarily mean that there’s anything wrong about the argument itself, all it may mean is that they don’t like the conclusion.)

I notice that you don’t present any actual argument as to what principle would limit the potential losses in freedom, under your proposal. You also don’t make any response to my observation that since government is run by people, if people make irrational decisions then we can expect government to make irrational decisions.

And yes, I do want to rig democracy to favour my preferences, who doesn’t? I’m a citizen of a democracy, when I vote I am hoping that the person or party I’m voting for gets in. When I vote in a referendum on a particular policy issue, I hope that the side I prefer wins. I think democracies should extend voting rights regardless of gender, race or sexuality, because I think a country is a better place when the government must take all those people’s views into account. When I argue in favour of a policy, or against, I do so because I hope to persuade other people to act democratically in a way that I prefer. You say that “nobody is proposing that we eliminate democracy”, but the fact that you apparently think that there’s something illegitimate about me wanting to rig democracy to favour my preferences, makes me wonder if your argument here does imply an ending to democracy. How could the democratic process work, if everyone was indifferent to what the outcome was? (That’s a serious question, btw, because I do think you are in favour of democracy despite what you’ve said about my argument.)

Tracy Wilkinson,

In a society where the costs of unhealthy eating are not fully born by the individual but by taxpayers (due to free healthcare) isn’t the taxation of dietary fat (and tobacco and alcohol and narcotics) a reasonable request from taxpayers? Of course, that highlights a fundamental problem: any welfare state is, to some degree, faced with a dilemma between free riding and a loss of freedom.

Patrick – actually, it’s just occurred to me, on rethinking, I don’t think that I made a slippery slope argument in the first place. The slippery slope argument is one that goes:

1. Event X has occurred (or will or might occur)

2. Therefore event Y will inevitably happen.

But I didn’t argue that adopting the principle you advocated would inevitably lead to the loss of freedoms I outlined. I pointed out that your principle would make legitimate some serious infringements on freedoms that I hope you and other readers think are important. Not that these infringements would inevitably happen, but that they might. Pointing out specific applications of a general principle is not a slippery slope argument. Plenty of countries have banned certain forms of speech, or certain associations, or certain religious practices, without imposing taxes on dietary fats. And such bans have often been justified by appeals to the general good and the costs that practitioners impose on society. (And in some cases, these are serious enough to make even me think they’re legitimate, to take an extreme example, banning human sacrifices).

W. Peden – that’s the whole question, what levels of infringement are reasonable? The idea that one can justify banning something just because there’s some evidence that it increases healthcare costs strikes me as pretty unreasonable, but this is in the end a case of preferences, there is nothing in logic alone that tells us what value to place on freedom versus minimising taxpayer costs. To take your case, voters voted for publicly-funded healthcare, or at least keep voting for parties that keep continuing it, is it not equally reasonable that we put up with the consequences, including that we might be paying higher costs in some places?

(I also note that plenty of countries without welfare states have infringed important freedoms, and indeed the welfare states generally rate quite highly on the various international indices of freedoms I have seen, so I’m not that worried about welfare states in particular. Perhaps only states that place a certain value on freedom itself can generate enough wealth and political stability to support welfare states, and perhaps too many limits on freedom means that we’d lose both the freedoms and the welfare state.)

Tracy W,

I wasn’t proposing banning dietary fat, but taxing it i.e. compensating other taxpayers for the cost.

“To take your case, voters voted for publicly-funded healthcare, or at least keep voting for parties that keep continuing it, is it not equally reasonable that we put up with the consequences, including that we might be paying higher costs in some places?”

There’s a fallacy of composition there: what is true of the electorate is not true of every elector. I may want people to pay the costs of self-inflicted harms from lifestyle choices and I may be unhappy about being coerced into paying their costs for them, but that state of affairs is consistent with a majority being content with such a system.

As for welfare and freedom, my argument was not so much that welfare DOES lead to infringements on freedom, but rather than it SHOULD.

W. Peden, my apologies for my sloppy wording. Please do me the kindness of reading what I earlier wrote as saying “The idea that one can justify taxing something just because there’s some evidence that it increases healthcare costs….”, as I can’t go back and edit it.

I however do not see how I have committed a fallacy of composition. From Wikipedia: “The fallacy of composition arises when one infers that something is true of the whole from the fact that it is true of some part of the whole (or even of every proper part).” I don’t see any point where I ever referred to the parts, I just talked about voters as a whole, and the fallacy of composition is dependent on someone talking about the parts and also about the whole. If you can suggest a wording change to make it clearer that I was only talking about voters as a whole, please do so.

As for the idea that welfare should lead to an infringement on freedom – congratulations, you have made me more negative about the welfare state. It’s interesting, I suspect that the concerns about infringements on freedom were brought up when the welfare state plans were being initiated, and were dismissed as slippery slope arguments, and here you are saying that those concerns about freedom were justified, at least in any society you’re voting in. Would you mind if I cite you in the future as a reason to think that the welfare state will lead to further infringements on freedoms? (Beyond the obvious one of higher taxes, all else being equal, of course).

from an economist’s perspective there should be no such thing as ‘irrational behaviour’. the division between rationality and irrationality is a subjective, moral judgement, not an objective, scientific fact. the sole challenge for economists should be to economise, i.e. to abstract from reality through reasonable simplifications to make predictions that are approximate enough to be of use to the public and to policy makers. thinking otherwise is confusing politics with economics. not that the two can be separated in reality, but that’s no excuse for not trying.

Tracy W,

I must now request charity on your part: I should have said “the fallacy of division”, not the falllacy of composition. What is true of voters as a group is not true of each and every voter.

I’d be overjoyed if my position was cited. As I see it, to the extent that we have a non-actuarial social insurance system, we cannot justifiably have personal freedom. Of course, if you ask me, so far as it is possible I’d rather have an actuarial social insurance system where individuals have both the responsibility and accountability for their decisions, with the string attatched only for those unable to do so.

One can see the movement towards the slippery slope in America right now with mandatory drug testing for those claiming benefits. Charities have known for centuries that providing welfare necessitates a reduction of freedom on the part of the person accepting it, even if that just means that someone in a homeless shelter cannot drink alcohol that night. I am not surprised that welfare state is moving in the same direction: freedom without personal responsibility is unsustainable.

W. Peden: “Charities have known for centuries that providing welfare necessitates a reduction of freedom on the part of the person accepting it”

Err, I think that charities have been paternalistic for reasons aside from necessity.