This summer I went to a conference for behavioural economists and economic psychologists. The presentations were entertaining.

Did you know that when coffee is given a fair trade label, people say it tastes better, even if it's just regular coffee? And fair trade coffee, without the fair trade label, doesn't taste as good?*

Did you know that an increase in a co-worker's pay will cause a person to reduce her own work effort?**

But somehow the intellectual excitement wasn't there.

Then I met Pete Lunn, an economic psychologist, who articulated the cause for my disquiet.

Economics, he said, is basically a deductive discipline. Psychology, on the other hand, is inductive.

It's a caricature, a gross over-simplification. But it has an element of truth.

Economists like to begin with a general model, work out its implications, and then go to the data to test the theory. Yes, there are applied economists who spend their lives trying to find out facts about the world. But facts in and of themselves are uninteresting unless they illuminate economists' view of the world, and can be explained in economic language.

Psychologists begin by observing people's behaviour, looking for generalizable patterns. For example, if people are observed acting as if they are averse to losses, psychologists infer that loss aversion exists. Yes, psychologists have conceptual explanatory frameworks, such as prospect theory, to explain such phenomena,but these theories are not the elegant mathematical creations favoured by economists. And where is the status and prestige? Look at the psychology journal rankings. There isn't a top-ranked journal with "theory" in the title.

It's a dilemma for behavioural economists. Yes, it's possible to go into the lab or into the field, run experiments, and see how people actually behave. To do what economic psychologists do, in other words. But what do you do next?

My co-author and colleague David Long sets out some options in his research on the nature of interdisciplinarity.

One is the multidisciplinary approach: take some psychology, take some economics, and use whatever works to explain the behaviour at hand. It's intellectual parallel play – working side by side, but not really interacting.

The danger of multidiscplinary is sinking to the lowest common denominator: combining economists' knowledge of experimental methods with psychologists' understanding of economic theory. The upside potential is arriving at better understanding of real-world phenomena than any one discipline could achieve individually.

Yet multidisciplinarity is not a stable long-run academic equilibrium. Parallel play isn't as fun as working with colleagues who share a common intellectual understanding. So multidisciplinary projects tend to morph into other things…

One possibility is what David Long calls "transdisciplinarity" or, less charitably, academic imperialism. Transdisciplinarity takes the paradigmatic approach of one discipline, and applies it to another discipline's subject matter. Economic psychology, for example, applies the methods of psychology to economic choices. Not every paper in the Journal of Economic Psychology simply reports the results of some laboratory experiment, but a lot of them do.

These papers are unsatisfying for someone who thinks like an economist, that is, deductively, because the results aren't integrated within a coherent overarching model of human behaviour. But they're a profitable line of inquiry for psychologists – intellectually, because they allow for a broader application of psychological methods, and also literallly, because there is a strong demand for research that tell firms how to sell more stuff.

What about behavioural economics? Mullainathan and Thaler describe it as "the combination of economics and psychology that studies what happens in markets in which some of the agents display human limitations and complications." Those limitations are bounded rationality, bounded will-power, and bounded self-interest, or altruism. The behavioural economics research agenda, according to Mullainathan and Thaler, is "identifying the ways in which behavior differs from the standard model," and "showing how this behavior matters in economic contexts."

Behavioural economics differs from economic psychology in that it is typically conducted by economists rather than psychologists, and published in economics journals. But is behavioural economics just the application of psychological methods to economics, or is it something more? Does it really involve economic thinking?

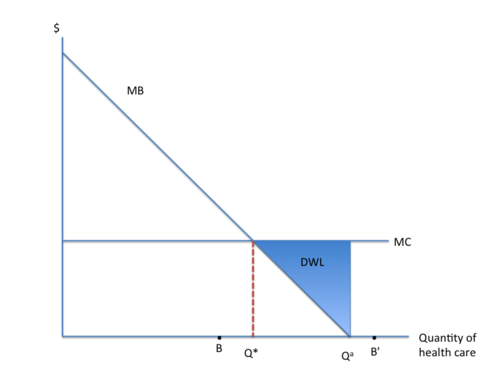

It might be easier to see what I'm getting at by looking at specific example, such as health care. The standard analysis of health care says that, if users do not have to pay the full marginal cost for their health care, they will demand excessive quantities of health care, and a deadweight loss will result:

In the diagram above, MB is the consumer's marginal benefit from health care services, which is assumed to reflect the actual benefit they receive from consuming health care, MC is the marginal cost to the insurer, society, or whoever pays in the end of providing the health care services. But the actual cost to the consumer, in this example, is zero. The optimal level of health care is Q*, where the marginal benefits of health services are just equal to the marginal costs. But because the consumer doesn't pay that full marginal cost, he or she actually demands excessive amounts of health care – health care for which the costs of provision are greater than the benefits – that is Qa. The consequence of this reckless overconsumption of health care is a misallocation of resources, shown as the deadweight loss (DWL) in the figure.

That's the standard analysis.

The problem is: people have no idea what the marginal benefits of health care actually are. So I'm sure that some behavioural economist could show that people's demand for health care was highly influenced by things like

- doctor's recommendations ("I'll see you in six months for another check-up") or

- the quantity of health care demanded by other people ("All my friends have had a complete body-scan, I'd better get one too") or

- awareness/salience ("Comedian David Mitchell has just been diagnosed with a fatal case of hurty elbow – my elbow has been feeling funny lately, I'd better get it checked out.")

O.k., so how does this get incorporated into the diagram above? Suppose that by manipulating framing, salience, or options, behavioural economists can cause people's demand for health care to go from Qa to some other point like B or B'?

Economists' policy recommendations – our ideas about which policies enhance economic efficiency and which ones detract from efficiency – are all based on the idea that individuals know what's best for themselves. That we can draw demand functions and use them to infer the marginal benefits to consumers of goods and services.

But if people's demands are just a product of framing, salience, and the public prominence of hurty-elbow syndrome, how can we use them to infer the marginal benefits to consumers of consuming health care? How can we make statements like 'the marginal benefits of health care are less than the marginal costs'? How can we make any inferences about the efficiency of different modes of health care provision?

The economic approach to policy analysis is deductive - economists begin with assumptions about consumers' and firms' preferences and behaviour, and these assumptions allow us to say things like 'insurance leads to excess consumption of health care services.' (Or 'firms will pass through savings from the elimination of PST on inputs to their consumers.')

Perhaps there is some way of including behavioural considerations into that framework. Perhaps we can say "the consumer's demand is really what is shown by MB, he just chooses to consume B because he is ill informed – but the happy thing is that, in this circumstances, there is no inefficiency resulting from the provision of insurance."

But that doesn't feel right to me – if a consumer's marginal benefit from consumption is something other than what is revealed by his or her demand I could just make up anything as a marginal benefit curve, and economics would become a completely ad hoc exercise.

Dabbling in economic psychology or behavioural economics is a little like taking the red pill – you go down the rabbit hole, and wake up realizing that the entire world is an illusion.

How can economists evaluate policy if they can't use people's preferences as revealed by their choices? We still need some way of figuring out which policies help people and which policies hurt people.

For example, opt-out policies have much higher take-up rates than opt-in policies. But in picking between and opt-out and opt-in policy, we still need to know in an ideal world, would we want a high take-up rate or a low-take-up rate? Causing people to opt-out rather than opt-into savings plans makes them save more – but if that causes excessive reductions in current consumption that might be a bad thing.

Once you fall down the rabbit hole, you just have to keep on going. If people's choices are not a reliable guide to their well-being, you have to turn to something else. Ask people how happy they are and measure well-being in terms of happiness. Evaluate health care spending by looking at objective measures of health, such as mortality, morbidity, or survival rates. Chuck out the entire elegant theoretical framework of welfare economics.

That idea has me, for one, reaching for the blue pill – after all, people aren't stupid, so standard economic analysis isn't a bad approximation of the real world, is it?

But I can't find one. I can't get all of that behavioural stuff outside of my head.

I want a purple pill – a merging of the red and the blue – that would allow me to merge behavioural insights into a coherent model of economic behaviour.

(Evolutionary economics – and other research programs that explain why humans behave the way they do – might have some promise as a purple pill).

But I don't know if such a thing is even possible.

* Christandl, F., Lotz, S., & Fetchenhauer, D. (2011). The Taste for Fairness – How Ethical Labeling of Consumer Goods Shapes People's Taste Experience. Talk. IAREP/SABE/ICABEEP Conference, July, 13th – 15th, 2011, Exeter (UK).

**Bracha, Anat; Gneezy, Uri; Loewenstein, George (2011) "Relative Pay and Labour Supply"

Where were you with your clear explanations when I was in grad school? I think I will send this post out to all of my colleagues.

This is a huge dilemma in health economics and health system planning. But throwing everything into the lap of Arrow and information asymmetry–a common highbrow rhetorical tactic–does not cut it, and you are correct to say we don’t have a good toolkit. You cannot indefinitely sustain something that grows faster than the economy, but evaluating productivity and quality is difficult. Even in a system where consumers pay 100% for health care, you cannot rely on revealed preference because people are subject to all kinds of suasion, aversion, and defensive over-consumption.

We also can’t underestimate the organizational politics where a huge, multi-billion dollar public program has been captured by occupational monopolies, and who lobby the public relentlessly. I was in Winnipeg recently and saw a pre-election sign from a union urging people to vote to “save” health care (i.e., “You only have one vote. Use it to save my job.”). The system is hardly under threat, yet some people buy that.

I think the behavioral economics of health care have more to do with individual decisions, but the economic impact of those individual actions is weak compared to impact of organized interests. Health care productivity is terrible and probably shrinking, even with new money. And there are few reliable measures of MB, especially when you want to target MB that is caused primarily by the health care system.

Frances,

“The economic approach to policy analysis is deductive – economists begin with assumptions about consumers’ and firms’ preferences and behaviour, and these assumptions allow us to say things like ‘insurance leads to excess consumption of health care services.’ (Or ‘firms will pass through savings from the elimination of PST on inputs to their consumers.’)”

&

“Once you fall down the rabbit hole, you just have to keep on going. If people’s choices are not a reliable guide to their well-being, you have to turn to something else. Ask people how happy they are and measure well-being in terms of happiness. Evaluate health care spending by looking at objective measures of health, such as mortality, morbidity, or survival rates. Chuck out the entire elegant theoretical framework of welfare economics.”

Why not just use BE to modify the assumptions and see where those get you? At the bottom of it all, people make the right choices when given the right information and/or the skill to evaluate said information. These two roles are performed by ‘institutions’.

If you disagree with the premise (at the bottom of it all), then psychology or BE will be no help either. Either BE or psychology can be used to insert premises/modify assumptions, or there is no knowledge to be gained. There has to be a link between means and ends no matter how feeble such a link is, if you want to be able to learn something about human behavior to predict it.

The fact that we in fact can and use economic tools to in fact build markets to attain certain ends, means that that this link exists. And BE and psychology can inform those models

Or to think about it in a different way, how did we ever get to the homo economicus if not through crude BE-experiments? Economic models are informed by our knowledge of the external world and BE and psychology merely add to it. The basis is sound.

Mike – your comment made me glow inside. Thank you.

Shangwen – as always, your insider knowledge of the Canadian health care system really adds to the conversation.

Martin: “At the bottom of it all, people make the right choices when given the right information and/or the skill to evaluate said information. These two roles are performed by ‘institutions’.”

What is the right information to give people? For someone working in marketing (where a lot of economic psychologists do work), this question is easy enough to answer: the right information is the information that gets people to buy stuff.

But what information would a benevolent dictator want to give people? The whole notion of a “right choice” assumes that there is some kind of stable underlying set of preferences, some one choice that is best – in other words, it assumes the premise that behavioural economics research calls into question.

Look, I haven’t swallowed the blue pill. Behavioural economics explains stuff that standard models can’t. But I think people underestimate the extent to which behavioural economics fundamentally challenges the basic economic paradigm, from Mankiw’s 1

Finishing that thought… people underestimate the extent to which behavioural economics fundamentally challenges the basic economics paradigm, from Mankiw’s 10 principles to the entire grad theory curriculum.

OLA – your comment has been unpublished. Further comments of this nature will lead to you being blocked from this site.

Okay, people’s choices are not a reliable indicator of their wellbeing. But is anything better? There’s a reason economists talk about utility rather than happiness – it’s quite possible to come up with situations where people value things above happiness (eg religious motivations). What right, in other words, does a psychologist, or any other ‘ist have to decide for me that my happiness is more important than my choices?

And, well, I’ve read a bunch of the psychology literature about our psychology, and nothing in that implies to me that psychologists, or economic behavioural scientists, are more free of the factors that lead us to make bad choices than anyone else. If a lay person’s demand for healthcare can be affected by framing, salience, or other options, why couldn’t a behavioural economists’ assessment of people’s choices be affected the same way? (This generally worries me about behavioural psychology that indicates that people are making bad choices, on the one hand I am inclined to believe it, on the other hand, the more I believe it, presumably the more I should distrust the people reporting said research and thus not believe it).

I wonder to how much extent the difference in the two approaches is simply another way of saying that experimental data allows you to be pretty agnostic about theory, while non-experimental data requires a model in order to make sense of it.

It occurs to me that the great recession/lesser depression is to economics what the LHC is to physics.

“I think people underestimate the extent to which behavioural economics fundamentally challenges the basic economic paradigm”

But if the old paradigm doesn’t explain the world as it really is, shouldn’t it be thrown out?

Another dilemma is economics as descriptive vs. prescriptive. Are economists trying to understand the world as it is or are they trying to layout a set of axioms by which we all must live? What if people decide they prefer to arrange the world in ways an economist would brand sub-optimal? Is it really sub-optimal if we prefer it? By contrast, physicists don’t face this conundrum (cats in boxes notwithstanding). Electroweak symmetry breaking works the way it works whether we like it or not. No amount of marketing or obnoxious talk radio is going to change anything.

I buy “Fair Trade” coffee because the package claims that it was not grown and picked by slaves. Whether or not it actually was not grown and picked by slaves, I don’t know, but it assuages my guilt about coffee a bit, I can afford the extra cost, so I generally buy it. How it tastes is not a consideration. With enough cyclamates in it and a touch of salt, any coffee tastes good to me.

“when coffee is given a fair trade label, people say it tastes better, even if it’s just regular coffee”

HA! My gut reaction was “gee, people are really hopelessly stupid”. Then I remembered that I buy fair trade coffee … because I think it tastes better. Oh well.

But then again, why couldn’t it really taste better? Why wouldn’t our brain wire together the taste of our coffee with our belief that the coffee was obtained through fair and mutually beneficial exchange with other humans. And if you value mutually beneficial exchange, why wouldn’t your brain reward you by making your coffee taste better?

Similarly, if you value getting the lowest price over all else, then maybe labelling the coffee with something conveying that message (Off the top of my head, I can’t think of anything that isn’t silly like “produced by slaves”), might make the coffee taste better for someone who values low prices.

Here (I think) is an example of a failed attempt to apply econo-behavioral thinking in an asymmetric context.

Hospitals have been trying to improve outcomes and control costs in surgery, where one cost to the system is the lengthy and sometimes complicated process of rehab. There is tissue trauma, muscle atrophy, and pain all getting in the way of recovery, so you need the aftercare. However, the cost of post-surg rehab was rising, and forcing out rehab patients in other areas.

So a bit of incentive-based thinking was tried, leading to “Prehab”, or a pre-surgical health improvement program. Depending on the surgery, this involves losing weight, strengthening muscles, better cardio health, quitting smoking, better diet, etc. etc., all before the surgery. But you would still get post-surg rehab, just less, hopefully.

Prehab has been promoted to patients on the usual basis–prevention–but in many settings it has also offered the ultimate Canadian get-out-of-jail card: a big bump up the surgical wait list. If you are fitter and thus likelier to have a better outcome, you might get the surgery sooner. So that was the incentive part. In Frances’s terms, you get higher subjective and objective utility in MB, and there is less DWL. That is good.

So what has happened? (BTW, I am not referencing published studies; I’m recapping discussions I’ve had with colleagues who did internal evaluations in these programs.) First, lots of people bought into it, because of the incentive (faster surgery). Not surprisingly, there is a noticeable education/income gradient in the uptaking population.

Second, total post-surg utilization of rehab has not declined. Medically, RCTs on prehab would suggest that there should be less need for it, but it is optional and not capped, so people consume it. One colleague said to me, “People just want to keep using it. That’s it.” So, people increased their consumption, going from Qa to B’ or B” (infinity and beyond?), thus driving up DWL or, more likely, inadvertently creating disutility for other rehab patients on different wait lists. The designers of prehab said, “the Red Pill is too costly. Take the Blue Pill and we’ll reward you,” but they did not prohibit people from taking both.

That purple pill was not purple. Back to the drawing board.

Stephen: “experimental data allows you to be pretty agnostic about theory, while non-experimental data requires a model in order to make sense of it.”

Interesting point.

Patrick – the same researchers also did some work with chocolate. They found that the brand of fair trade chocolate that they used in the study actually did taste better. In otherwords, even when they put the non-fair trade label on the fair trade chocolate, people still ranked it more highly than the other chocolate. It’s also relevant, I think, that the study was done with German undergrads – as you say, you might not get the same results with a random selection of Wal-mart shoppers (I asked the speaker about this, and he told me that there are no Wal-marts in Germany so the question doesn’t arise).

Ed – I do too.

Tracy W: “What right, in other words, does a psychologist, or any other ‘ist have to decide for me that my happiness is more important than my choices?”

I think you’ve perfectly articulated the “blue pill” position there – the fundamental attraction of the economic way of thinking.

Patrick “Another dilemma is economics as descriptive vs. prescriptive. Are economists trying to understand the world as it is or are they trying to layout a set of axioms by which we all must live?”

Well, given economists’ willingness to pontificate on the virtues of HST, free trade, competitive markets, etc etc I think the answer has to be that economics-as-we-know it is prescriptive. And behavioural economics calls many of these prescriptions into question.

Shangwen – another fascinating example.

Do people play too much tennis? Or too little?

An economic psychologist or behavioral economist may be able to tell us lots of true things about what tends to make people play tennis more or less frequently (a regular partner to play with, recent media coverage of tennis, whether there is a tennis court nearby and whether it charges fees or is paid for by the state, etc.), but would we conclude that has offered us any insight into whether people are playing the optimal amount of tennis? Should we worry that the fact that there are a bunch of factors that have been demonstrated to make people more or less prone to tennis-playing challenges our basic economic paradigm (to swipe a phrase from Frances Woolley above)?

I would hope that most people see that the very notion of an optimal amount of tennis to play that doesn’t put the individual’s preferences at the center of it all is strange, maybe even disturbing. You have to start from there, or the whole thing is meaningless. That’s not to say that an economist or a behavioral psychologist has no useful insight to offer the tennis player: they might well be able to point out that given how often you play tennis a membership at the local club that you can walk to is cheaper in the long run than driving 20 minutes to the “free” municipal courts if you value your time more than $X, or that if your goal is to play tennis every morning as part of your exercise regime you’re much more likely to do it if (say) you place your racket and tennis clothes where you can see them upon waking up or have a standing date with a tennis partner. But it hardly strikes me as a failure that they can’t tell you, “Really, in the best of all possible worlds your MB curve ought to slope like this.” And the fact that you wouldn’t want to play as much tennis as you do if you hadn’t just watched the US Open is an interesting psychological phenomenon, not an indictment of the entire notion that your preferences ought to be respected.

“Behavioural economics differs from economic psychology in that it is typically conducted by economists rather than psychologists”

I thought Kahneman, Tversky and Ariely were the prototypical behavioral economists. All of them have backgrounds principally in psychology rather than economics.

Economics, like Darwinian Biology, is an empirical / causal explanatory science. It isn’t an inductive or experimental science.

Economics begins with a problem raising patterns in our experience, most importantly the pattern whereby individual plans are globally coordinated as if part on one larger plan, and prices tend toward costs, and where there is an extensive division of labor.

And this problem in our empirical experience is explained by a contingent causal mechanism: learning and changes in judgment by people in the context of changing relative prices and local conditions.

Learning and changes in judgment are a causal force — causally explaining global design-like order in the coordination of individual plans in a society with property and prices.

The FACT that economists don’t understand HOW there field is a science leads to the great pathology of what the telite in academia attempt to produce as “science” in their quest for status, tenure, financial reward and academic power.

@Joshua:

As Arnold Kling noted, when discussing the desire to impose one’s own preferences on others, “In some ways, behavioral economics is even worse. Instead of saying, ‘I would rather that you not eat a high-calorie dessert,’ the behavioral economist says, ‘I claim to know better than you whether or not you would really like to eat a high-calorie dessert.'”

That is part of the ethical dilemma–there has been so much elite chatter and enthusiasm for BE, one suspects it has just become cover for highbrow coercion.

Wonks: “I thought Kahneman, Tversky and Ariely were the prototypical behavioral economists. All of them have backgrounds principally in psychology rather than economics.”

And Richard Thaler, too. Yes, it would have been more accurate to say “done by economists and/or published in economics journals.”

So when Kahneman publishes in a psych journal that’s econ psychology, when he publishes in an econ journal, that’s behavioural economics?

Honestly, I’m struggling to figure out the difference…

On Stephen’s point: not sure experiments allow for model agnosticism. It’s more a system of keeping everyone honest. Experiments and models kinda go hand-in-hand. Usually you do experiments to test the predictions of your models. It’s rare to do experiments for their own sake (though obviously it did and does happen – especially in areas where we really know very little).

Isn’t behavioural economics ‘controversial’ precisely because it goes into the world and finds that many of the predictions of standard econ models don’t predict what actually happens in reality? And that makes some economists uncomfortable.

And if one is a prescriptive economist, finding that reality rejects your deeply held axiomatic system of rules for right living … Ouch.

Standard econ is also potentially cover for coercion if it’s used prescriptively. Nothing new there.

Isn’t BE’s point that people will still choose to eat the high-calorie dessert even if they are fully aware of and understand all the bad consequences?

I suppose you can set in contrast to standard econ rationality, and say it’s ‘bad’. Or you can update your models of the world to reflect the fact the people really do behave this way…

Tracy W: “What right, in other words, does a psychologist, or any other ‘ist have to decide for me that my happiness is more important than my choices?”

My 13-year old judges that a $20 pair of sneakers is worth $100 because there is a worthless “swoosh” on the side. This preference is conditioned by billions of dollars of ad spending, without which, he would choose to pay $20 for a pair without the swoosh. And don’t tell me that he’s better off for reasons of improved signalling of mating prowess, or whatever. That’s a zero sum game, so no improvement in DWL. Along with some other sectors, the marketing industry is really nothing but DWL (It’s worse than dead weight loss in fact – for example we probably consume the wrong drugs because of marketing).

So the problem is not that we need be more respectful of peoples subjective preferences. The problem is that those preferences are, objectively speaking, stupid.

As a Engineering grad, I have a different perspective than an economist. I think it’s one of the points of friction between Frances and myself. I’m a trained model-breaker. When I see a model, my first reaction is to hit it with a hammer. I want to smash it. Why? Because that tells me how robust it is, what inputs I can feed it to get the behaviour I want rather than behaviour that is uncontrolled and dangerous.

To me Economists rely far too much on deduction and model authority. If it comes from the model, it must be authoritative. Engineers do not trust models that can’t be verified and have defined limits put on their input for stability. Our job is to separate the useful input from the dangerous.

The Economist’s mind sees the world a logical place. The Engineering mind accepts that the world is illogical but tries to make it logical, just a little bit and tries to warn everyone about the boundaries and limits of that effort. As a result we are far more comfortable with throwing out a discredited model and getting a new one that works.

It results in an iterative design process but that’s how most design works in real life. It has to. To me it seems that Economists are much more uncomfortable with being iterative.

Patrick “Isn’t BE’s point that people will still choose to eat the high-calorie dessert even if they are fully aware of and understand all the bad consequences?”

One of the most valuable things I’ve learned from BE is that if I put cookies in an opaque container I’m less likely to eat them. Clear glass containers should only be used for healthy foods like carrots.

This can be embedded in some kind of model of meta-preferences, where people choose what kind of containers to put their food in – a variant on the bounded-rationality-as-a-rational-strategy approach of Herbert Simon and followers. I don’t see this as being so much a part of the modern BE agenda, but quite likely people are doing research in this area that I’m not aware of.

K: “The problem is that those preferences are, objectively speaking, stupid.” – I’m torn – yes, I agree with you on the stupidity of spending huge amounts of money for swooshes, but at the same time my inner economist is always there quietly saying “people aren’t stupid. respect people’s choices whatever they happen to be.”

K – you have the right to decide for your son because you’re his parent. But he’s going to turn 18, and then I understand that as a matter of law you lose that right.

I believe in freedom of speech, and freedom of thought, so I’m totally okay with you not respecting other people’s subjective preferences. But I believe in freedom of speech for everyone, you’re free to disrespect other people’s subjective preferences, and they’re free to disrespect you for disrespecting their preferences, or for any other reason they care to apply, and so forth.

To take your last point, “these preferences are, objectively speaking, stupid”, well, fine, but if my preferences are, objectively speaking, stupid, how can I decide whether a pyschologist, or any other ‘ist, is smarter than me, and thus competent to decide such matters for me, or for other people? If I’m not competent to make decisions for myself, I’m certainly not competent to make decisions about who should be making decisions for me, or anyone else. To put it another way, for all I know, all those psychologists and behavioural economists that Francis Woolley cites might as well be the moral equivalent of Nigerian email scammers and thus objectively speaking the worst thing I could possibly do for myself is to defer to their judgements. And the more that the psychologists or other ‘ists argue that people like me are irrational, and the more data they provide to support their hypothesis, the less confident I am that I should be drawing any conclusions based on their research at all.

Greg Ransom, there are experiments in evolutionary biology. Principally drosophilia, but also nematodes and even Russian silver foxes.

Tracy W : There’s not getting away from making a value judgement. One could ask “what’s so great about freedom of speech?” – and plenty of places in the world do (e.g. China – the producer of swooshes). Do you think the marketer who is trying to get your money by tricking you to change your preferences is respecting your freedom?

I dunno (honestly). If you feel better after you’ve been tricked and spent the money, even knowing you’ve been tricked then who am I to pronoun otherwise?

“As a Engineering grad, I have a different perspective than an economist. I think it’s one of the points of friction between Frances and myself. I’m a trained model-breaker. When I see a model, my first reaction is to hit it with a hammer. I want to smash it. Why? Because that tells me how robust it is, what inputs I can feed it to get the behaviour I want rather than behaviour that is uncontrolled and dangerous.”

If you’ve ever been to a PhD seminar in economics, that’s all it is – one person presenting a model and a dozen people swinging hammers at it.

Yes, exactly. Non-economists who visit our seminars are sometimes shocked at how stormy things can get. I understand that at the Chicago econ dept, it’s considered to be a major achievement if the presenter can get past the first slide.

O/T: The Russian silver fox study is fascinating. I’d recommend reading up on it.

Patrick, but if the scientists are right, how can I trust them when they tell me that I’m being tricked by a marketer?

Consider some of the other possibilities that could explain the scientific results Frances describes (note, by “normal” I am referring to people with functional brains of the sort that psychologists and the like do this sort of research on, as opposed to people in a coma or living in remote villages that have never been contacted by scientists or the like):

– Marketers only are interested in tricking CEOs and other such people who pay marketers. They are nefariously taking advantage of scientists’ natural human irrationality to get them to publish research falsely indicating that normal people’s preferences are set by marketers. The scientists honestly believe that their research is correct.

– Marketers and scientists, being normal people, are irrational. The marketers irrationally but honestly believe that they can influence normal people’s preferences, and the scientists irrationally but honestly come to the conclusion that marketers can do so, even though objectively the marketers have no effect.

– Scientists are evil, and have set out to take advantage of normal people, by publishing this sort of research. You, James Woolley and I are too dumb and/or irrational to figure out what their end objective is, or another possibility is that I’m too dumb, and you and James Woolley are nefariously in on the plot.

– Scientists keep publishing research indicating that people aren’t influenced by marketers, but I am so irrational that I keep reading it, and summaries of it, as indicating that we are.

The more convincing the research that people like me make decisions irrationally, the less I think I can trust said research, or indeed anything else that goes on in my brain.

As for respecting freedom of speech, the best arguments I’ve seen for this are in chapter 2 of J.S. Mill’s “On Liberty”. But hey, if I’m irrational, I could be totally wrong about the value of J.S. Mill’s arguments, and I could be totally wrong in whatever I think about the marketer you refer to. (To be honest, your question on this point and on the tricked one, sound to me like loaded questions along the lines of the infamous “have you stopped beating your wife?”, as I can’t see that I expressed any opinions relevant to the presuppositions contained in said questions.)

I have always found BE to be the foil to regular economic models as it highlights examples where the regular models don’t work. As Shangwen points out, it is too simple to say “asymmetric information” or “monopoly power” and look solely at the Industrial Org text books. People choose to do things that inevitably mess up theories.

Newtonian theories work incredibly well almost all the time. When they don’t work they are wrong. Fortunately for physics, Newtonian formulas are a special case of more general equations. Maybe in economics there is no General Formula that covers all situations. Maybe there are categories where in different situations the tools need to be completely different. I can use my toolbox to work on my clothes but my wife’s sewing kit is much more helpful. But don’t use the sewing kit to install a new plug…

One of the brain teasers I struggle with is why do only business students cheat at Prisoner’s Dillema? Everybody else cooperates and achieves the group optimal result – the commerce, econ, & MBA students cheat (or act in their “own” best interest depending on your perspective) and ruin it for everybody. So who is making the “bad” decision – and why?

K: the swoosh is valueles. But Joe Bain, father of industrial economics once said( IIRC from memory)” From a use of resources pov, we should all wear Mao suits size 40. Yet we don’t”.

A fashionista is someone who is like everyone before anyone is like her. And when everyone is like her, she no longer is.

The Roman empire was probably expanded by senators coming home and having their teen-age daughter telling him that “Calpurnia has a new red toga and a Greek cithar-playing slave and I only have last year blue one and a Thracian flute player. I hate you!.” He give her a bag of sesterces and go find calm battling some germanic tribes.

Preferences are there and are our constraints.

And no I don’t believe in the power of marketing. The two big lies in marketing are the same one from both practitionner and opponents: that marketers have a lasting influence. If they had,our backyards would filled with whatever is sold by the best ad agency.

Peter McClung: “One of the brain teasers I struggle with is why do only business students cheat at Prisoner’s Dillema? Everybody else cooperates and achieves the group optimal result – the commerce, econ, & MBA students cheat (or act in their “own” best interest depending on your perspective) and ruin it for everybody.”

What’s odd, though, if that if you get 10 or 15 economists together for dinner at some conference, hand around the total bill and ask everybody to pitch in, there will almost always be a large surplus. So does that mean we don’t free ride, or that we’re more concerned about status, waiting until everyone is watching and then throwing in a $50 or a pile of $20s, than about free riding?

Somehow the explanations offered by BE often seem hollow…like all those evolutionary psychology theories that bring everything down to mate selection. Should there be Anthropological economics too? I like this address given by Mark Chaves, an anthropologist and president of the Scientific Study of Religion.

Here he is talking about puzzling inconsistencies in religious behavior, or “religious congruence”. In it, he tells the story of a tribal shaman who is asked by an anthropologist if he is going to perform a rain dance, because the tribe is experiencing drought. The shaman answers, “Don’t be a fool, whoever makes a rain-making ceremony in the dry season?”

Frances – your comment about dinner reminds me of my undergrad days when a fellow who had literally escaped Nigeria as a communist and showed up on campus. It was before my time so I do not know the precise details but he went to the Marxist economists and asked for help. They effectively turned him away (as I say, I’m not sure of the precise details but they had no practical help for him). He came across the curmudgeonly classical economist and in desperation also asked him for help. In contrast, the free-market advocate invited him home to live until he could get himself sorted out.

Somewhat off-topic, but I never understood why loss aversion was seen to be such a great insight. If marginal utility is declining, then we’d expect people to prefer avoiding a $100 loss over the prospect of gaining $100. It’s just garden-variety risk aversion, isn’t it?

Frances, Peter: I highly recommend a textbook by Samuel Bowles ‘Microeconomics: Behavior, Institutions, and Evolution’. In it he shows how we can incorporate behavioural and evolutionary game theory to explain a ‘cooperate’ solution in social settings e.g. sharing bill for dinner. Nothing ground breaking as I found out there’s in fact a lot of literature on this stuff but Samuel Bowles textbook was first time I encountered it. There is a lot of good stuff in there incorporating eclectic theory such as behavioural and evolutionary game theory and applying it in a political economy setting that I never imagined existed until I came across it in that book.

I think it’s important to make a distinction between positive and normative economics. Sure economists have models about utility maximisation etc. but that doesn’t mean that they should act like the actors in their models or that’s how they think people should act so I don’t see any inconsistency between showing altruism and generosity in social settings and assuming that individuals are self-interested in the models. The latter is about explaining phenomena that may be observed while the former is a value judgment on how they should lead their lives.

On a related point I think it’s also important to define ‘rationality’ really carefully. Anecdotally at least I think people get into needless arguments about economic models because they are arguing about different things.

Stephen, “It’s just garden-variety risk aversion, isn’t it?” I think what’s different is that there’s a kink, and the kink moves around. So if you start out at $1000, then you get really upset about going down to $900, but if you were at $900 to begin with, then you’re only moderately thrilled about going up to $1000.

Garden variety risk aversion, on the other hand, gives the same absolutely value change in utility whether you’re going from $900 to $1000 or from $1000 to $900.

DavidN – thanks, I like Sam Bowles’ work.

Peter, interesting story.

Ah.

What is it with all the economists named Woolley on this thread?

Are they some sort of clan who all chose to be economists?

Tracy W: Ask the marketer. It’s no secret that they are trying to convince to do something you wouldn’t otherwise do by means other than presenting information. Thus scantily clab hotties in beer commercials rather than IBU and SRM numbers.

Along comes the ‘ist telling why the scantily clad women increase beer sales.

What effect does that have on liberty?

Stephen,

You may be interested in this paper:

Click to access Rabin_EasyCalibrationTh00.pdf

Basically, the argument is that if diminishing marginal utility was the source of risk aversion, then everyone would accept a positive payoff bet provided that the stakes were small enough.

But in studies, people with a net-worth of, say, $500,000 will still not accept a bet in which they lose $1 on heads and gain $1.05 on tails. That implies implausible utility functions.

And moreover as roughly the same proportion of households turn down the bets (independent of their wealth level), there must be something else going on behind risk aversion, other than just diminishing marginal utility of wealth.

Well, economics could do what other disciplines dealing with very complex systems do – model some basic elements, test them, do some experiments, gather data, add some more elements, test again, stop every so often to check the whole for coherence, map and state as clearly as possible the current limits of knowledge. And match the process to the degree of change in the systems (eg, military theory, in which every solution generates new problems, is much more ad hoc than, say, climatology). So take BE seriously, and stop de-funding economic history. An alternative is to stick with arguing about slightly different basics for another century or so. The latter clearly pays better.

Not to quibble, but Psychological Review and Personality and Social Psychology Review (both listed on the top journals list you linked to) are exclusively theory journals. I suspect a number of others are as well.

There’s more to psychology than the empirical novelty acts that get published in Psychological Science.

It seems lazy to dismiss the conceptual basis for an entire discipline based on the methodology of searching for the word ‘theory’ in a list of journals.

Shangwen on September 01, 2011 at 01:10 PM: Your colleagues’ trial wasn’t a failure! They tried an intervention to shape patient behavior, and Nature gave them a clear result. The world’s store of knowledge gained an increment – we know one intervention that won’t work. We move on and try something else. But Frances is right – ‘Once you fall down the rabbit hole, you just have to keep on going’. Don’t expect theory to be much help. Gather as much data as you can about the particulars of this problem. It seems patients make their own decisions when to exit rehab, so well-designed structured interviews could help your colleagues understand how patients decide, and what information (and, yes, incentives) might influence those decisions.

Determinant reminds us that engineering is iterative. The engineering of behavior is no exception, in fact it is more so. (It happens to be my profession, under the name of human-factors engineering or engineering psychology – my degree is in experimental psychology). And it is necessarily highly empirical – practicioners spend a great deal of time in data collection in field studies, part-task experiments, low- and high-fidelity ‘human-in-the-loop’ simulations, and in interviewing, conducting surveys, etc., amassing the facts that Frances finds boring. Maybe not elegant, but we have our successes.

Patrick – I think in your attempts to get me to talk about, or to, marketers, you are trying to avoid the implications of my basic point – that the more we believe the scientists’ evidence that we make decisions irrationally, the more we should be very doubtful about said evidence.

(Although what do I know? Perhaps you and James are really trading recipes for dandelion wine and I’m just irrationally thinking it’s a debate about the implications of psychology and behavioural economics and the like).

Tracy W – who is this James person?

Ken – ” amassing the facts that Frances finds boring”

Don’t get me wrong – this stuff sells. I wrote up some of that labelling effect research in my globe and mail column and got a lot of traffic.

The nudges blog is fun to read, as is a lot of this behavioural economics research.

But for me, personally, there’s a kind of intellectual play that you get from econ modelling – it’s what makes economists draw curves on napkins or use the salt, pepper, and any other objects on the table to explain a model of trade flows. And I don’t get that from BE.

Bork – fair cop.

Actually, no, engineers and scientists are /much/ more respectful of models than economists. Go to an economics presentation and a significant percent of the time is people trying to break, discount, or demolish the model.