A couple of weeks ago, I noted that as far as I could make out from available data, rates of job creation returned to pre-recession levels more than a year ago. This time, I'm going to try to get a handle on the gross flows on the other side of the market – that is, in and out of unemployment. What are the rates at which workers are losing and finding jobs?

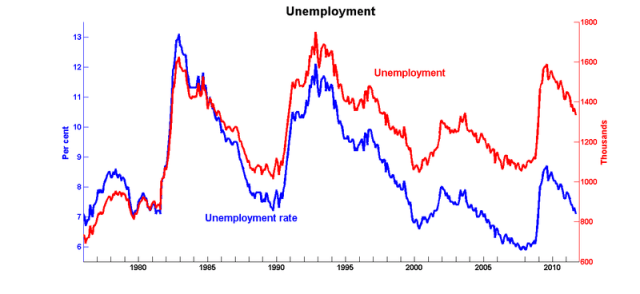

First, here is the graph of the number of Canadians unemployed and the unemployment rate (see also this E-Lab post) :

Unemployment increased by about 400,000 during the recession, and half of that jump has been absorbed since the peak in August 2009.

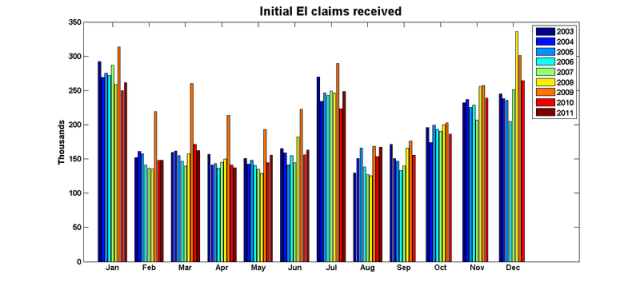

Although we don't have data for the flows into and out of unemployment, there are data for initial EI claims. These numbers will necessarily exclude those who aren't eligible for EI, but movements in EI claims should more or less correspond with flows into unemployment. As was the case for new hires in the post on job creation, the data have a strong seasonal pattern, so the data are grouped by month so as to more easily identify movements that deviate from the usual seasonal fluctuations:

Once again, the scale of these flows is remarkable: in a good month, some 150,000 people make initial claims for EI. (Separations would include those who left one job for another without passing through a period of unemployment). The sharp rise in unemployment is associated with the 8-month spurt of higher-than-usual new claims between December 2008 and July 2009. New claims over the last two years have been in the usual range of variation.

What are the prospects for those who are unemployed? There are two ways to look at unemployment spells: ex post and ex ante.

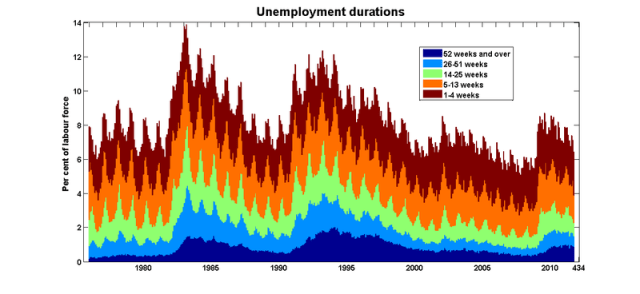

The data in Cansim Table 282-0047 provide a breakdown of how long people have been unemployed, conditional on being unemployed in a given month. These are ex post data, in the sense that these are durations that have already been observed:

One of the more worrisome aspects of unemployment is the deterioration of human capital: the longer one is out of employment, the greater the risk that one's skills will lose their value on the job market. So although 2/3 of the unemployed have been so for less than 3 months, the uptick in long-term unemployment is something to keep an eye on, although it appears to have leveled off in the past few months. (The US version of this graph is here.)

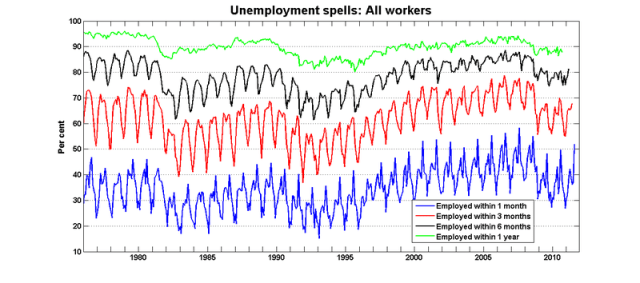

But for someone who is unemployed, the ex ante duration is the more pressing question: how long it will take to find employment? There is of course no way of answering that question for any particular person, but we can tease out some average probabilities from the unemployment duration data.

In August 2011, there were 1.516m people unemployed, and there were 729,000 people who were unemployed for 5 weeks or more in September 2011. This suggests that 1.516m – 729k = 787,000 (52%) of the those who were unemployed in August found a job within the next month. If we extend this reasoning further, we can construct raw probabilities that an unemployed worker will find a job within a given horizon:

The effect of the recession on the probability of finding a job within a certain period of time appears (to me, at least) surprisingly small. The chances of finding a job within 1, 3 or 6 months aren't particularly low by historical standards.

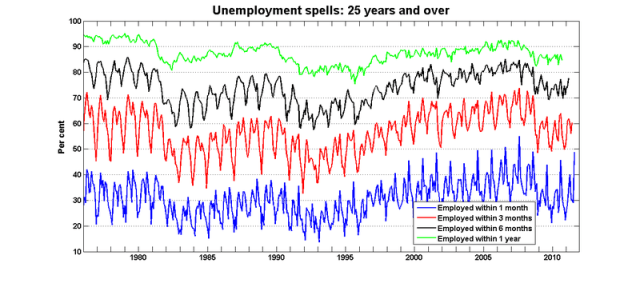

Unemployment spells have different effects for younger workers, so let's break that down. Here is the same graph for those aged 25 years and over:

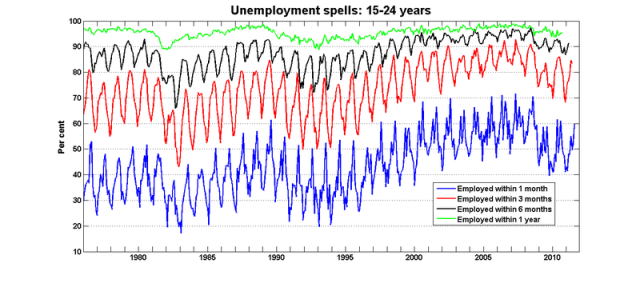

And here is the graph for those aged 24 and under:

Once again, conditions have deteriorated slightly since before the recession, but the chances that an unemployed youth will find employment in a certain period of time are still better than they have generally been over the past 35 years.

The amount of 'churn' in the labour market is something that doesn't seem to be appreciated widely enough. I get the impression that too many people think that the unemployed are akin to a stagnant pool that is being drained at a painfully slow rate consistent with the first graph. But that's not the case at all.

Great information. This downturn doesn’t intuitively seem as tough on young people as previous ones, although I wondered if it was just me, because this time I’m neither young nor unemployed. The last graph shows how much worse things were for unemployed young people in the early 1990s (when I left Canada for US grad school).

But since people are still complaining, I’m wondering if there is some data on the types of jobs being done, on involuntary part-time work, or maybe real wage levels or wages compared to the price of basket of goods over time? I`m asking if there is any economic data that shows whether young people have it so much worse off today?

(housing prices maybe? and not to buy a bungalow in Vancouver, but maybe to rent a small apartment? or is it just that “expenses” are up (computer, iphone, latte habit, clothing tastes, etc.)

What would be really interesting would be to take that first unemployment graph, and overlay the governing party in Canada on the bottom of the chart. We might get a nice picture of which governing party has been better for unemployment.

Why have employed and unemployment diverged so much?

I’d also look at “self-employed” as well as underemployment (the US tracks part-time workers due to economic reasons as a measure of this).

Frances – I’m not sure what you mean.

Stephen, I meant the unemployed and the unemployment rate. But I get it now, it’s due to population growth, and # of unemployed is in ‘000s. It would be interesting to compare unemployed/population and unemployed/labour force i.e. unemployed/(employed+unemployed).

Hi,

Interesting post. Ont point though, you say:

“In August 2011, there were 1.516m people unemployed, and there were 729,000 people who were unemployed for 5 weeks or more in September 2011. This suggests that 1.516m – 729k = 787,000 (52%) of the those who were unemployed in August found a job within the next month.”

I think you need to also need to take into account flows from unemployment to Not-in-labour-force (NLF). Stephen Jones’ CPP 1993 paper shows that these flows are pretty big (he had monthly hazard rate at .22 from unemployment to employment vs. .17 from unemployment to NLF).

Gah – you’re quite right. I should have thought of that.

Damn. Maybe I can get something from participation rates….

“But since people are still complaining”

Complaining I guess because they have jobs, but perhaps neither the job nor the wage they wanted. Haven’t wages been fairly stagant? That would cause unhappiness to build-up over time.

How do you document working at a gas station or on shifts at a call centre for $12/hour when you got a degree and wanted to go into something with $40K and 9-5 hours?

There is a statutory bias to encourage that behaviour in the EI system and it’s reinforced through cultural and social norms in Canada.

But the person in that situation is caught in a Stag Hunt problem: they can’t find an employer who will pay them enough and provide them opportunities to reach their full potential.

This is why when I heard a recent piece on CBC about a think tank wanting Canada to become an economy of the educated and high-skilled I wondered “Yeah, and where are we going to get the financial capital to set up those companies and enable them to take that kind of risk?”

Skills doesn’t mean much if you don’t have the financial capital to exploit them.