Health economist Uwe Reinhardt in a recent Economix Blog posting noted the recent rates of U.S. health spending growth for 2009 and 2010 reported by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services were marked as the lowest rate in the 51-year history of the National Health Expenditure Accounts. Indeed, the growth rate for 2009 was 3.9 percent. Reinhardt examines the question if this development is evidence that we have finally “broken the back of the health care inflation monster.”

That is, nominal health spending may be starting to grow at a rate either at or below the nominal GDP growth rate. He argues that while it is tempting to view this decline in growth as a step in the direction of getting health spending under control, he argues that it is probably premature. It could be that this drop is simply a lagged effect of the deep recession.

He does ask why it might be reasonable to assume that health spending will eventually not grow faster than GDP or even more slowly. According to Reinhardt,

“Economists would explain such a trend as flows: as the fraction of G.D.P. devoted to health care increases, the added satisfaction, or utility, that people derive from added health care is likely to diminish relative to the added satisfaction derived from consuming more of other things. It could explain a gradual decline in the excess growth of health care spending. Finally, economists retreat here to the one law on which they all agree, namely, Stein’s Law, named for the late economist Herbert Stein: “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” Trust us. It will, in the long run.”

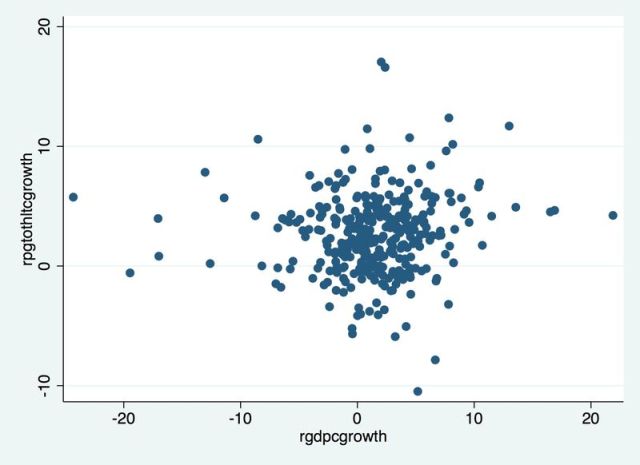

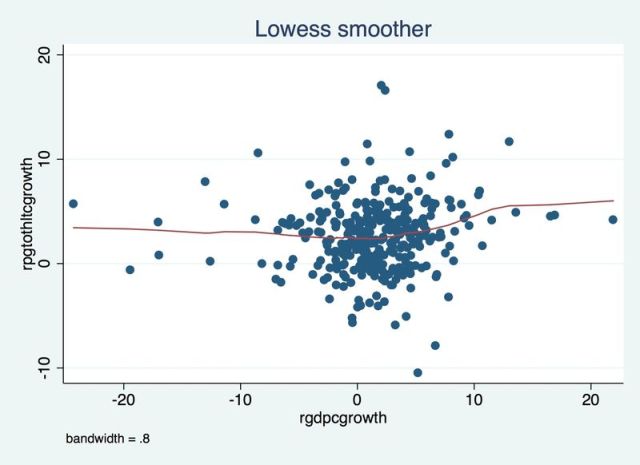

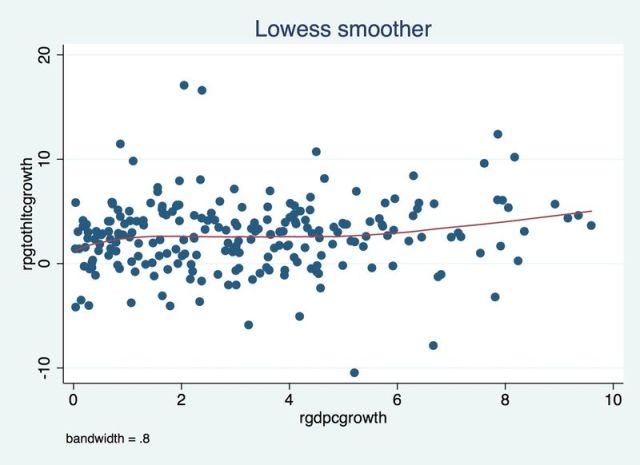

As income rises, will health spending eventually grow more slowly than income? I decided to take a look at this potential relationship using real per capita growth rates in GDP and health spending. I took real per capita GDP and real per capita provincial government health spending for Canada’s provinces for the period 1975-2009 (data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information) and calculated the annual growth rates. They are plotted in Figure 1 and they show a scatter relationship between the growth rate of real per capita GDP (rgdpcgrowth) and real per capita provincial government health spending (rpgtothltcgrowth)that looks positive but there is an awful lot of dispersion. I then also fitted a non-parametric trend using LOWESS – locally weighted scatter plot smoothing – to see if there was a non-linear trend thart showed a slowdown in health spending as income rose. Figure 2 suggests that the growth of provincial government health spending is pretty invariant to income growth when it is negative and positively related when per capita income growth is in the 0 to 10 percent range. The relationship then tapers off and flattens again once real per capita GDP is growing faster than 10 percent. However, real per capita GDP growth rates below zero and greater than ten percent definitely seem to be outliers so lets try it again by omitting them. The results are shown in Figure 3 – there does not seem to be any tapering off as growth rates rise. In the case of provincial government health spending, the data for the period 1976 to 2011 suggest that the growth of real per capita provincial government health spending has been pretty invariant to real per capita income growth. Indeed, a linear regression of the natural log of real per capita provincial government health spending on the natural log of real per capita GDP yields an elasticity of 0.59 – fairly income inelastic. While health spending growth rates do seem to vary with income growth in a non-linear fashion, expecting health spending growth to taper off as we become richer may be wishful thinking.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Try regressing it on Federal transfers. My take on this is that the rellatively high growth over the past decade is due to transfers being maintained at 6%, making up for cuts in the 90’s. If the feds choke increases down the provinces will adjust.

Thanks Livio. I was just reading this on Friday (original paper here). Although his paper is about the US, many of his comments about political dynamics (and reference to Peter Orszag’s doom-laden paper) are relevant to Canada.

I am puzzled by the assertion that HC spending/consumption should taper off with rising wealth due to diminishing returns (though I am macro-ignorant). This hasn’t been the case since 1970, why should it be so now? And when something is centrally allocated, veiled in guild interests and mystique, and people are fundamentally allergic to assessing its real value, why should it be sensitive to any economic variable other than the policy willingness to rob Peter yet again?

An interesting natural experiment, which I don’t see a lot of comment on, were the big cuts in the 90s. The cuts were quite substantial and widespread, yet we did not see the big spikes in nosocomial or iatrogenic morbidity and deaths that many predicted. I was still an undergrad then, but I remember the squawking. Yet the one thing no one talks about is that the “austerity” of those years forced HC systems to innovate and have a serious look at improving value. This led to a dramatic drop in post-surg bed days, development of more coordinated care, and serious ops-management attempts to control wait lists. In other words, we developed better organizational capital out of it, and few people today demand an overnight stay after a tonsillectomy. For all the cuts, there was a utility-enhancing change in social norms.

Jim:

Good point on the transfers. Will take a look.

Shangwen:

Thanks very much for the paper reference.

The invocation os “Stein’s Law” here is intended both as a cautionary comment and a bit ironically.

Suppose that right now real health care spending is 15% of real GDP per capita. Suppose real GDP per capita grows at an average annual rate of 2% and real health care spending grows at an average annual rate of 5%. In 67 years, real health care spending will be 101.6% of real GDP per capita…which (this being Herb Stein’s point) is seems somewhat difficult…