In a previous post on the housing market, I noted that we were unlikely to see the sorts of interest rate increases that would generate increases in mortgage payments of the size we saw in the early 1980s (up to 60%). And it's a good thing too, because most new homeowners are not as able to absorb those sorts of increases the way new homeowners were back then.

This difference is that the economics of mortgage debt in a low-inflation environment are quite different from those of the high-inflation world of the early 1980s.

Suppose that a household with an annual income of $50,000 is buying a $100,000 house. Let's consider two scenarios:

- Low inflation: Inflation is 2%, and the interest rate is 6%.

- High inflation: Inflation is 6%, and the interest rate is 10%.

Note that the real interest rate in both cases is 4%. We'll assume that there's no real wage growth, so wages increase with inflation. (In this exercise, I'm not going to make any assumptions about how housing prices evolve. This limits the number of questions that can be answered.)

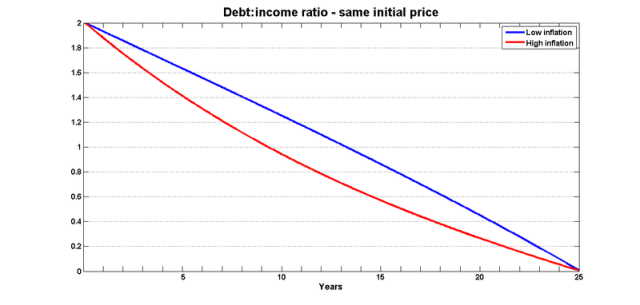

Lower inflation and interest rates mean that the mortgage is paid off faster:

Even so, the debt-income ratio falls faster in the high-inflation case:

The difference in the rate at which the nominal debt in the numerator is reduced is not enough to counter the higher growth rate of the nominal income in the denominator.

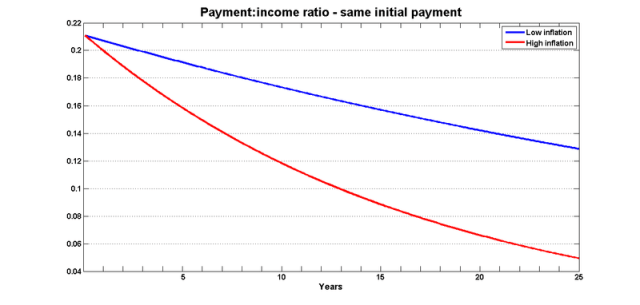

Part of the story is of course that the initial payments are much higher in the high-inflation case:

(In this graph, monthly payments and monthly income are being compared; the debt-income ratios are at the annual frequency.)

In the high-inflation case, the payment-debt ratio is still above that of the low-inflation case after five years, but the reduction is greater. If (say) the payment:income ratio increases by five percentage points when the mortgage is renewed, the high-inflation homeowner would still be operating in familiar territory. That wouldn't be the case for the low-inflation owner.

But the story doesn't end here. I've been assuming that the house price would be constant across the two scenarios and that the low-inflation homeowner would make lower monthly payments. But it seems to me as though a more plausible assumption is that initial monthly payments would be the same. In other words, the low-inflation homeowners would use the lower interest rates to leverage themselves into a more expensive house.

In this example, the low-inflation homeowners buy a $140,000 house and make the same initial monthly payments as the high-inflation owners pay on their $100,000 house. (Note that this sort of increase goes a long, long way in explaining the increase in housing prices in the past 20 years.) Here is the evolution of the remaining balance:

That higher initial leverage never goes away:

And here is the ratio of monthly payments to monthly income:

Once again, an increase of mortgage payments equivalent to (say) 5% of income would be more easily absorbed by the high-inflation owner.

So add this to the list of reasons to worry about the Canadian housing market. In a low-inflation world, homeowners are more highly-leveraged and hence more vulnerable to increases in mortage rates.

[This is the second of a three-part series on the housing market. The third post is here.]

Yep. In the olden days, we used to describe this effect as “front-end loading”. As in “the higher nominal interest rates in a high inflation environment cause mortgage payments to be front-end loaded”.

The simple rules of thumb that people use to decide whether they can afford a mortgage (less than x% of income) can’t handle changes in inflation properly. The rules of thumb that work under one inflation environment don’t work under a different environment. Sort of Lucas Critique.

We’ll assume that there’s no real wage growth, so wages increase with inflation.

What has happened in Canada over the past 30 or 40 years is that families have been able to increase their income by having more earners – Nicole Fortin has an interesting paper arguing that female labour force participation is driven, in part, by the need to pay the mortgage.

But now that the majority of women in the home-buying age bracket are in paid employment, there isn’t a lot of room for further growth along these lines.

This is why older homeowners talk about the payments “getting easier”. Look at the the 10-year anniversary: payments are almost down to half their initial level in the high-inflation case (versus four fifths in the current example) . Now, to be fair, it is real rates that have fallen a lot in the last 20 years since inflation has been stable, close to 2%. Focusing on the real mortgage rate allows us to see just how exceptional this environment is and the multiple ways it can go wrong for homeowners (credit component of nominal rate grows OR inflation shrinks).