This is a long and boring post. (Though some will no doubt find it highly controversial, and a very few might even get over-excited). It might be useful for economics students who want to put the Loanable Funds theory into perspective. They are my main intended audience. And maybe for those who teach them too.

Loanable Funds is a theory of "the" rate of interest. (I'm coming back to that "the" later). There are other theories of the rate of interest. That's why we call it a "theory".

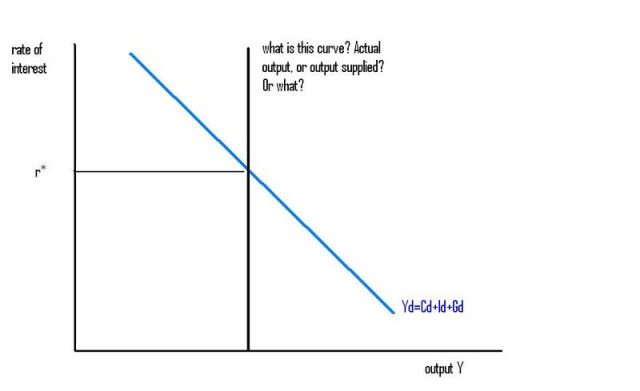

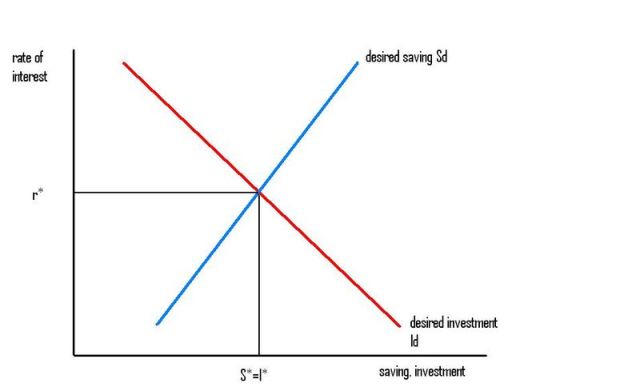

Most (all?) economics students will have seen this diagram:

Put the rate of interest on the vertical axis. Put the flows of saving and investment on the horizontal axis. Draw a downward-sloping desired investment curve Id. Draw an upward-sloping desired saving curve Sd. Mark the point where the two curves cross. Draw a horizontal line to the vertical axis, to find the rate of interest predicted by the theory. The Loanable Funds theory says that the rate of interest is determined by the intersection of the desired saving and desired investment curves. (The rate of interest and actual saving=actual investment are co-determined simultaneously by those two curves.)

"Saving" has to be defined as "national saving", to include both private and government saving. And investment has to be defined as "national investment", to include both private and government investment. Otherwise things won't add up right.

Even then, things won't add up right in an open economy, unless we include borrowing from abroad and lending to abroad. Which means you have to bring in expected changes in the exchange rate, otherwise foreign and domestic interest rates won't always be the same even under perfect capital mobility. For now, let's just stick with a closed economy.

With a little bit of national income accounting, there's a second way to look at the Sd=Id equilibrium condition of Loanable Funds. Desired private saving Spd is income minus taxes minus desired consumption. Spd=Y-T-Cd. Add desired government saving Sgd=T-Gd, and we get desired national saving: Sd=Y-Cd-Gd. So we can re-write Sd=Id as: Y-Cd-Gd=Id. And we can rearrange that to get:

Y=Cd+Id+Gd

One of the joys of National Income Accounting is that it lets you see that two theories that sound very different are really the same. "The rate of interest equilibrates desired saving with desired investment" can be re-stated as "The rate of interest equilibrates desired expenditure on newly-produced goods (Cd+Id+Gd) with the output of newly-produced goods" (Y).

And a second joy of National Income Accounting is that by doing this it can reveal an ambiguity in the theory. Because we might want to replace Y (actual output of goods) with Ys (the quantity of output supplied, or that people and firms would like to sell). So that we could restate Loanable Funds as "The rate of interest equilibrates the supply and demand for newly-produced goods". But that means that "desired private saving" is ambiguous too. Does it mean "Y-T-Cd"? Or should it mean "Ys-T-Cd"? What does "desired saving" mean in Loanable Funds? Does it mean "Actual income minus demand for consumption goods"? Or does it mean "The income we would earn if we could sell all the output we wanted to, minus demand for consumption goods"? That difference is obviously going to matter, if the economy is in a recession with deficient aggregate demand, so we can't sell as much output as we would like.

Here's a second diagram for the loanable funds theory. Even though it's equivalent to the first diagram, by an accounting identity, you maybe haven't seen loanable funds presented this way:

What exactly does the vertical black curve represent? Is it actual output (actual income)? Is it the level of output supplied, which means the level of output that people and firms would like to sell (and the income they would earn if they did)? Or something else?

Let's put that question aside for now, and consider an alternative theory of the rate of interest.

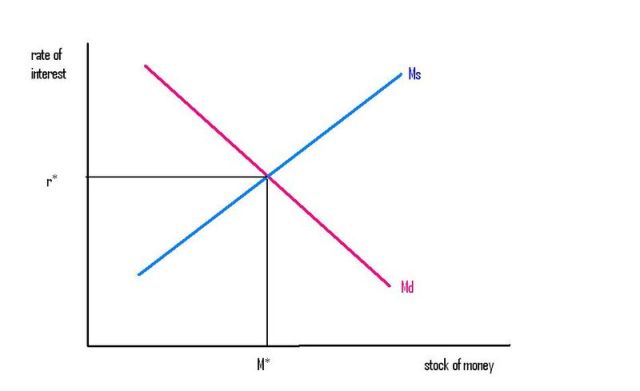

The Liquidity Preference theory of the rate of interest is the most obvious alternative. The rate of interest is determined by the supply and demand for money. Put the rate of interest on the vertical axis, the stock of money on the horizontal, draw a downward-sloping money demand curve, and an upward-sloping money supply curve, and the rate of interest is determined where those two curves cross.

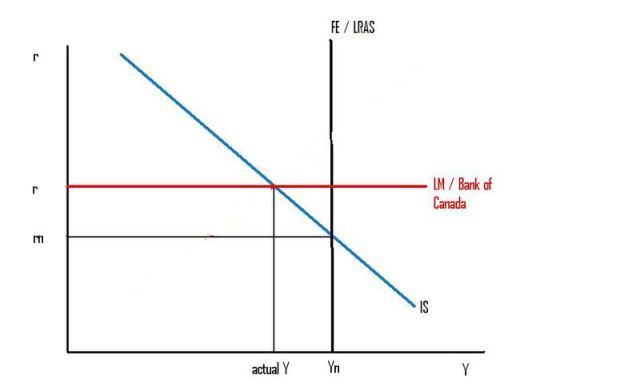

Almost every Canadian is familiar with a special limiting version of Liquidity Preference theory. It's the theory that gets reported in the news. "The Bank of Canada sets the rate of interest" is a Liquidity Preference theory. You can think of this as a limiting case of Liquidity Preference, where the money supply curve is perfectly elastic at a rate of interest chosen by the Bank of Canada.

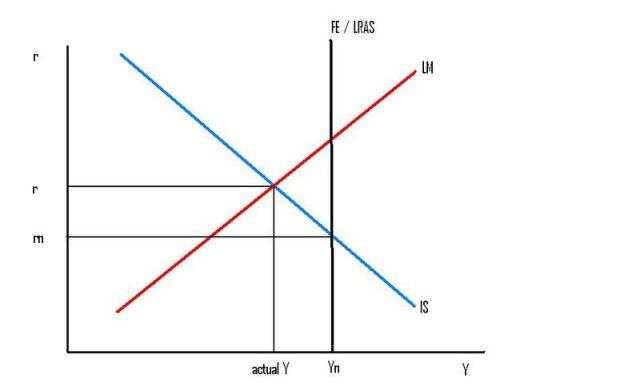

Most (all?) economics students have been taught both Loanable Funds and Liquidity Preference. And they have been taught one way to reconcile the two theories. They have been taught the ISLM model. The IS curve represents the Loanable Funds Id=Sd equilibrium condition, and the LM curve represents the [Liquidity Preference] Md=Ms equilibrium condition. But each is incomplete, because Y affects Sd (and maybe Id too), and Y also affects Md (and maybe Ms too). So you need to put both curves together to get the complete picture. The rate of interest (and the level of output Y) are co-determined by the IS (Loanable Funds) curve and the LM (Liquidity Preference) curve.

But in the long run, when sticky prices have adjusted to the demand and supply of money, we can ignore the LM curve. [Update: because the price level adjusts so the LM curve shifts endogenously to interesect the other two curves.] The level of output is determined by the Long Run Aggregate Supply curve (or the "Full Employment" curve). So in the long run, money demand and money supply have no effect on the rate of interest. The rate of interest is determined by the intersection of the IS and FE curves — by desired saving and investment at the long run equilibrium level of output determined by LRAS.

Now let me tell you a second way of reconciling the Loanable Funds and Liquidity Preference theories. (It's not inconsistent with the ISLM way of reconciling the two theories, but it does sound very different. It's really just a special case of the ISLM way, but it sounds much more real worldy).

The Bank of Canada sets the rate of interest. But the Bank of Canada does not set the rate of interest on a whim. Something determines where the Bank of Canada chooses to set the rate of interest. The Bank of Canada targets CPI inflation at 2%. It tries to set a rate of interest that will deliver 2% inflation.

If the Bank of Canada sets the rate of interest "too high" (as in the above diagram), output demanded will be "too low", so actual output will be "too low", and inflation will start to fall below the Bank's 2% target. And if the Bank sets the rate of interest "too low", output demanded will be "too high", and inflation will start to rise above the Bank's 2% target.

So, what does "too high" and "too low" mean? Relative to what? It means "relative to the rate of interest at which output demanded would be at the right level to keep inflation at the 2% target". In the above two diagrams, I have called that rate of interest "rn", and that level of output "Yn". The Bank of Canada sometimes uses the names "neutral rate of interest" and "potential output". Some economists call them the "natural" rate of interest and level of output. Others use the name "NAIRU". Others use the name "Full Employment". Names sometimes have connotations, so people fight about names. But I'm going to skip that fight here.

Instead, I'm going to go back to a question I left unanswered: what does "Y" mean (and what does "Sd" mean) in the Loanable Funds theory? Because we now have a useful answer: "Y" should be interpreted to mean "that level of output compatible with inflation staying at the Bank's 2% target". Define "desired saving" to mean "what the the level of desired saving would be if output (income) were compatible with inflation staying on target" and we get a nice way to reconcile loanable funds and liquidity preference theories of the rate of interest:

The rate of interest is set by the Bank of Canada, but the Bank of Canada tries to set the rate of interest equal to the rate of interest predicted by the loanable funds theory, where desired saving equals desired investment at potential/natural/NAIRU/full employment output.

[Digression:

What I have sketched above represents the "mainstream"/New Keynesian/Neo-Wicksellian way to reconcile the loanable funds and liquidity preference theories. But before passing on I want to note briefly three possible problems with that reconciliation:

1. The Bank of Canada is trying to hit a moving target (the "natural rate of interest") that it can't see (except, barely, looking backwards). So it will miss. But when it misses the target that will have real effects on the economy (if it sets a rate of interest too high, it will cause a recession, for example). Those real effects may themselves have persistent effects on the economy, and so may move the target from where it would have been in future. It's like trying to hit a moving target you can't see and where your misses themselves cause the target to move.

2. The IS curve may slope up, and probably will slope up if tight monetary policy causes a fear of prolonged recession which reduces desired investment and increases desired saving.

3. There are (in this highly-aggregated model) three goods: output; bonds; and money. It is very tempting to think that three goods means three markets, and that one market can be dropped by Walras' Law. But Walras' Law does not apply in a monetary exchange economy. And in a monetary exchange economy with n goods there are (n-1) markets, one for each of the non-money goods, where it is exchanged for money. There is no "money market". In this case n=3. There is an output market where output exchanges for money, and a bond market where bonds exchange for money. There is no market where bonds exchange for output (it would be a barter economy if there were). But the IS curve implicitly assumes people and firms are looking at the trade-off between output and bonds.

End of digression.]

Other Alternative(?) Theories:

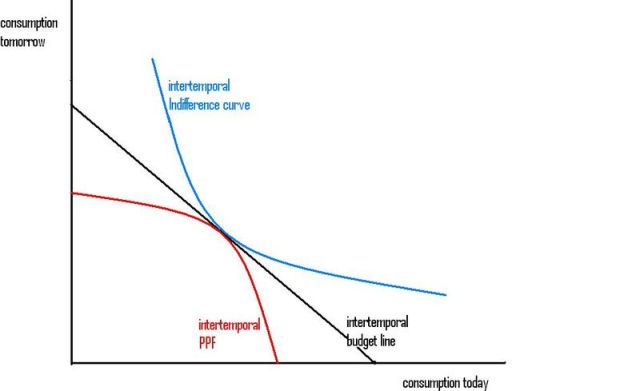

1. The Irving Fisher diagram. You may have seen this diagram:

Equilibrium is where the Production Possibility Frontier and an Indifference curve kiss and the same budget line is tangent to both. It's exactly like the standard micro diagram where you have quantity of apples on one axis and quantity of bananas on the other. Except here you have "apples today" on one axis and "apples tomorrow (or next year)" on the other.

The slope of the budget line equals (1+the rate of interest). According to the Irving Fisher theory, the rate of interest is determined by intertemporal preferences and intertemporal production possibilities. In equilibrium, 1+the rate of interest (slope of budget line) equals the Marginal Rate of Intertemporal Substitution (slope of indifference curve) equals the Marginal Rate of Intertemporal Transformation (slope of PPF).

It looks very different from the Loanable Funds theory diagram. But really, it's exactly the same. You can derive the Id and Sd curves in the loanable funds diagram by varying the rate of interest (and so varying the slope of the budget line) and watching for the new tangency points on the PPF and Indifference curves. The tangency with the PPF tells you how much firms want to divert resources away from producing output for current consumption towards investment for output of future consumption. The tangency with the Indifference curve tells you how much of their wealth people want to spend on current consumption and how much thay want to save for future consumption.

2. Walrasian/Arrow Debreu General Equilibrium theory.

This theory is exactly the same as the Irving Fisher diagram, only with loads more dimensions. Lots of time periods, instead of just two. Lots of different goods, instead of just one. Lots of different people/firms, instead of just one. Lots of different states of the world (uncertainty), instead of just one (certainty).

3. The "The rate of interest is determined by the marginal product of capital" theory.

This theory ignores intertemporal preferences. It is not really a theory. It's either a misstatement of the equilibrium condition of the Irving Fisher diagram as a one-way causal relationship, or a special case of the Irving Fisher diagram where the PPF is a straight line so preferences don't affect the slope of the tangency. Or it assumes indifference curves are L-shaped. Or it assumes there is only one output good that can be switched costlessly between consumption and investment and that the stock of that good ("capital") does not change much within the period and can be taken as a predetermined variable. (For example, what happens to the Solow Growth model if people suddenly decided they didn't care at all about the future and wanted to eat the whole capital stock right now?)

4. The "The rate of interest is determined by the subjective rate of time preference" theory.

Same as the above theory, only the other way around. This one ignores intertemporal production possibilities. It's either a misstatement of the equilibrium condition as a one-way causal relationship. Or it assumes the indifference curves are straight lines. Or it assumes the PPF is reverse-L-shaped.

5. The "Start with Walrasian/Arrow-Debreu General equilibrium theory, make some simplifying assumptions, forget about the intertemporal preferences, and then say "Oh Look! the rate of interest is indeterminate, so it must be determined by my pet theory instead"" theory of the rate of interest.

Again, not really a theory. More of a non-theory. Useful only as a critique of the "the rate of interest is determined by the marginal product of capital" non-theory, which also ignores preferences. (And even then, the simple Irving Fisher diagram can make the same point more simply and in a much more constructive way. Yes, in general you need to look at preferences as well as technology to determine things like interest rates and other relative prices.) An awful lot of ink has been wasted on this subject.

6. All the other theories I've either forgotten or am too tired to talk about.

[Update: 7. Euler equation. Same as Irving Fisher, only in math not pictures.]

Loose ends:

Aside from the problem of how exactly the loanable funds theory works in the short run in a monetary exchange economy, the biggest problem with the loanable funds theory is that it talks about "the" rate of interest.

Even when we are talking about nominal rates of interest, there are lots of different assets, that all differ by term, risk, liquidity, etc.

Let's just look at the term structure.

Most investment projects have costs and benefits that come at many different time periods, not just costs today and benefits tomorrow. When you look at the Net Present Value to see if the investment is profitable, you will have to look at the whole term structure of interest rates. You can't just assume there is one equilibrium rate of interest for all terms. (Not just empirically, but theoretically too, because with one rate of interest an n-period NPV calculation becomes an n-degree polynominal equation with up to n different solutions for the rate of interest at which NPV=0, which is what the "re-switching" debate was all about).

In principle, this is no problem. You just switch from the 2-period Irving Fisher diagram to a mult-period version. But in practice it's a problem. The desired investment curve (and desired saving curve too) will shift if excepted future interest rates change. So you can't solve for what the current period loanable funds diagram is telling you without solving a whole sequence of loanable funds diagrams. Then you have to ask how people form expectations of those future equilibrium interest rates, when some people are planning to invest or save in future but haven't entered into forward contracts. Expectations matter. And if you expect the Bank of Canada might make a mistake in future, it becomes even more complicated.

Now let's look at the distinction between real and nominal interest rates.

Suppose the Bank of Canada had always been targeting 3% inflation instead of 2%, and suppose it were always expected to go on targeting 3% instead of 2%. If money were "super-neutral", then no real ("inflation-adjusted") variable would be affected by the inflation target. The loanable funds theory would then predict that the nominal interest rate would be 1 percentage point higher, but the real interest rate would be unaffected. (Both desired investment and desired saving curves would shift vertically up by 1%, because borrowers and lenders care only about real interest rates, not nominal). Loanable funds would then determine the long run real interest rate, and we would have to add the nominal inflation target to get the long run nominal interest rate.

Empirically, that seems to be roughly true, in that countries with higher inflation rates over long periods do tend to have higher nominal interest rates. But it is unlikely to be exactly true. If it were exactly true, it wouldn't matter what inflation rate the Bank of Canada chose to target.

Even if monetary policy were super-neutral in the sense defined above, so it makes no difference to real interest rates if the Bank of Canada targets 3% instead of 2% inflation, that is not the only sense that matters. The Bank of Canada currently targets the Consumer price Index. It could also target some other price index, or the price of gold, or the price of wheat, or almost any other nominal variable. And it will probably matter, in real terms, which target variable it chooses. Targeting 2% inflation for the price of fresh strawberries would probably have very bad consequences for the economy. A bad strawberry harvest would probably cause a massive recession, as the Bank of Canada tried to bring all other prices down to prevent the price of strawberries rising faster than 2% per year. And God only knows how a stupid monetary policy like that would affect saving and investment.

For any given monetary policy target, there will be a time-path of nominal interest rates set by the Bank of Canada that could hit the target. But when we talk about the real interest rate, since the real interest rate is the nominal interest rate minus inflation, there are many different measures of inflation (because there are many different goods and many different bundles of goods, and the CPI is only one of millions) and so many different measures of "the" real interest rate. Bear that in mind as we return to look at the open economy version of the loanable funds theory.

The simple loanable funds model won't work in an open economy. That's because we can also borrow from abroad or lend from abroad. The Sd=Id equilibrium condition gets replaced by Sd=Id+desired Net Lending to Abroad. And the Ys=Cd+Ig+Gd equilibrium condition gets replaced by Ys=Cd+Id+Gd+desired Net Exports.

The usual fix for this problem is to say that loanable funds determines the world interest rate (the world is a closed economy, so the world interest rate is determined by equilibrium between world desired saving and world desired investment). And then perfect capital mobility ensures each country has the same interest rate as the world.

But if the Canadian nominal exchange rate is expected to depreciate, the Canadian nominal interest rate would be higher than in the rest of the world, by an amount equal to expected depreciation. And if Canada produces different goods from the rest of the world, there is no reason to expect that the real exchange rate between Canadian goods and foreign goods will stay the same over time. So the Canadian real interest rate could be either lower or higher than the real interest rate in other countries, even with perfect capital mobility, and even in long run equilibrium.

If wheat is expected to rise in price relative to oats, then the real interest rate calculated by subtracting wheat price inflation will be lower than the real interest rate calculated by subtracting oat price inflation. If Canada produces and consumes mainly wheat, and if foreigners produce and consume mainly oats, then the Canadian real interest rate (with lots of wheat in the price index) will be lower than the foreign real interest rate (with lots of oats in the price index). You will need to figure out what is happening to the relative price of wheat and oats if you want to say what determines the Canadian real interest rate.

I think that is the major practical problem with the loanable funds theory of the rate of interest. In an open economy, it's not enough to talk about Canadian saving and investment. It's not even enough to talk about world saving and investment. You need to talk about world saving and investment, and Canadian saving and investment, plus how the relative demand for canadian vs foreign-produced goods is expected to change over time.

This isn't complete. But it's already far too long. And I'm tired.

This is a great teaching post and covers a lot of ground.

Here are two comments:

1) You are using a static model to look at dynamic adjustments.

I.e. “if the central bank changes r to r'”. And I’m not sure how you can do that. For example, suppose that at the current level of savings, the interest rate that maintains price stability is 4%. But really you mean a total return of 4% — a rational person will look at total return. That total return can be obtained by a 1% interest rate and capital gains of 3%, or a 4% interest rate and capital gains of zero. The capital gains can be obtained by the interest rate being cut.

So a time path of cutting rates can give a time path of total returns so that price stability is maintained. At least until you hit the zero bound. Cutting rates in the dynamic model can be the same as the static model with a rate increase.

Similarly, a time path of raising rates can cause negative total returns and be equivalent, in the static model, to a rate cut.

So there is a inconsistency when thinking of the static problem versus the dynamic problem. But you are using the solution of the static problem to analyze changes in rates or savings demands. I find this really troubling.

2) Why is the LRAS curve vertical? Many east nations have adopted development policies that, at least over near to medium term, greatly increased the LRAS curve as a result of keeping nominal interest rates low. Are you really saying that the LRAS curve is independent of nominal rates? So a nation can set nominal rates to, say, the natural rate + 4%, and this nation will have the same long run output as a nation that sets the nominal rate to the natural rare -4% ? I think it more likely that this nation will have a permanently lower capital stock. Changes in nominal rates are going to affect total output even in a two good model, because total output is aggregated by a price deflator, and the relative prices of capital/consumption goods are going to change so that total output changes.

I think you need a one good model to conclude that total output is independent of inflation.

rsj: Thanks! (That’s really what i was trying to do.)

“1) You are using a static model to look at dynamic adjustments.”

If we assume certainty, and that the Bank of Canada always gets it right, no problem. Just lend me an n-dimensional chalkboard for the n-dimensional Irving Fisher diagram (or a tame mathematician) and I can solve for the whole time-path.

But if the Bank of Canada ever misses, and is expected to maybe miss in future, that opens up a whole can of monetary worms. Including upward-sloping IS curves. Which is one of the reasons I want us to move away from thinking of monetary policy as setting a rate of interest, even in the short run.

“2) Why is the LRAS curve vertical?”

Actually, if we draw the LRAS curve in {r,Y} space, it probably slopes up. At a higher real interest rate, we want to consume fewer apples this year and more apples next year. Similarly, at a higher real interest rate, we want to consume less leisure this year and more leisure next year. (Some RBC models work on this channel). (I ducked that to keep the pictures simple and standard).

If we draw the LRAS curve in {inflation, Y} space, it will probably slope backwards. Because higher inflation screws things up, if there are sticky prices, that people don’t want to change, so output supplied falls. Or it might slope up, if there is absolute downward sticky nominal wages and/or prices. If you let me rig all the assumptions, I can build a model to make it vertical. But the game isn’t worth the candle. Empirically, it seems to slope backwards at very high inflation rates. But at least part of that will be reverse-causation (screwed up policies cause low Y and also high inflation). The data are just too dirty. All we’ve got is theory, plus some indirect data. Too much endogeneity. “Roughly vertical” is roughly defensible.

Re: 1, no that’s not what I mean. The central bank cannot get things right because it can only use the short rate where total teturn is the rate. But investment is long term and savings is also long term. If in the long term it wants rates to be higher, in the short term, total return will be lower. The curves depend on total return. Therefore it is impossible to escape a period of time when the CB makes things worse and not better when it wants rates to go up or down. Then you need to measure the length of this time period versus whatever price stickiness you have.

Nick

1, 3 and 4 are all the same – I find it very hard to imagine why there would be a subjective time preference that would be in disequilibrium with the marginal product of capital. If the rate of interest does not adjust, employment/output adjust to create the equilibrium. The equilibrium condition of S&I is not a very interesting phenomenon in and of itself, or, the IS curve is most probably horizontal.

You’re right to recognise the challenges to loanable funds in an open economy. But I tend to think that this is a relatively simply conclusion from your assumptions – a world where real exchange rates may not be constant is impossible to reconcile with a world where real interest rates are the same. But there’s a different challenge, which does not require liquidity preference or an open economy.

Your conception of loanable funds is one of saving – it is the standard conception. But loanable funds, properly specified, is not about saving, it is about financing. Financing is the same as saving only if the credit equations in the economy do not change. As Leijonhufvud details painstakingly (and Claudio Borio does for the modern era and audience), there are numerous processes – financial deepening being the most obvious one, varying the percentage of retained earnings by firms being another – which ends this equivalence.

So even if you have a ‘pure’ loanable funds theory of interest, it does not necessarily follow that the S-I equilibrium will always be a full-employment one. Money is not a veil, but neither is finance.

My favourite way of thinking about ‘the rate of interest’ is to imagine a linear dial that says :

time preference/ MEC (income or accumulated flows) —-(LF)—-financing (cash flows, instantaneous flow)—-(LP)—- portfolio allocation (asses, or stocks).

Loanable funds (LF) sits between time preference and financing. Liquidity preference (LP) sits between financing and portfolio allocation.

The natural rate is given by an interaction of financing and time preference/MEC, or LF. (E.g. a period of easy financing – which does not need to correspond to a period of excess (desired) savings – tends to drive down the MEC/ natural rate without any ‘real shock’ whatsoever. When asset prices have been high, businesses need even higher prices to invest further.)

The market rate is given by an interaction between LP and LF. Whether the two are in consonance is dependent on the shape of the LM curve.

The standard neo-classical method has been to begin with the natural rate and assume that the market rate must be bounded by this plus transaction costs. As David Glasner shows, this is what Earl Thompson did – his model is basically your option 3. This is the kind of model that leads to the capital controversy debates – about the heterogeneity/ costs of switching capital etc. I believe that we don’t really need such a model anymore.

The most satisfying neo-classical model, the benchmark case of showing the ‘equivalence’ between LF and LP, is the Fischer Black model. He took Fisher’s capital theory in its entirety (all input was capital, and human capital was quantitatively the more important type) and took it to its logical conclusion – he collapsed the usual economist’s distinction between quantities and prices. Thus, we move focus from the incomprehensible heterogeneity of assets of the economy to the more systematic heterogeneity of its liabilities, because there is an elaborate system in the market economy that tries to price this heterogeneity. Capital is wealth, wealth is capital. When asset prices fluctuate, capital fluctuates.

I like to imagine this as a large, strong bridge being put together between time preference and portfolio optimization, parallel to my linear dial. While early neo-classical theories had a variety of just-so stories that assumed this bridge (with Arrow-Debreu being the crowning moment in the just-so-ness of these stories), Fischer Black is the one who showed what that bridge actually was. The only GE that even remotely makes sense is the CAPM.

(As an aside, I often like to imagine that a very strong pull along this bridge sometimes causes the initial dial to crack open at the cash flow junction. This is ‘the Minsky moment’.)

Throughout this, my conception of ‘the rate of interest’ is the ‘cost of capital’, not the short rate. That’s also the rate of interest in the axis of my IS and LM curves. The short rate is a parameter, a tool in the hands of the monetary authority that could potentially set and move the cost of capital, but sometimes fails to do so.

rsj: As an extreme case of the problem you are talking about, suppose there’s a lag in investment decisions. We decide this year on how much investment we will do next year, and that depends on this year’s expectation of next year’s interest rate. So the BoC must set next year’s interest rate this year. It’s gotta promise (or lead people to expect) it will set the right interest rate next year, when the BoC doesn’t even know what people are currently planning for next year.

No problem in a world of certainty, because the BoC can figure out what people are planning to invest next year, and can promise today to set interest rates next year to keep I=S next year. But yes!

Ritwik: I’m afraid you really lost me there.

Let’s take an extreme case. Pure consumption economy where output of the consumption good is exogenous, so the PPF is reverse-L-shaped. You can define an equilibrium interest rate in the Irving Fisher diagram, (the slope of the I-curve at the endowment point) even though there’s no capital.

Sure, it’s a weird case, but the Irving Fisher diagram can handle it. How would Fischer Black handle it?

Ritwik: “The only GE that even remotely makes sense is the CAPM.”

And you really lost me there. I would say that CAPM is partial equilibrium. It’s not even a theory of the rate of interest. It’s a theory of interest rate differentials that takes the rate of interest on safe assets as exogenous.

It’s gotta promise (or lead people to expect) it will set the right interest rate next year, when the BoC doesn’t even know what people are currently planning for next year.

This requires time inconsistency on the part of agents. A long term rate will only fall if it assumed that a sequence of short term rates fall. So to credibly get long term rates to fall, the CB needs to promise low short term rates for a prolonged period. But if, in so doing, it shortens the recession, then you are requiring either false expectations on the part of investors — e.g. tricking them into believing that short term rates will be lower for the next 10 years, even though we exit the recession in one year — or you are promising short term rates to be too low for the next 10 years, veering away from your inflation target.

But you cannot both adhere to the inflation target and respond to fluctuations in savings demand.

rsj: you have lost me.

Let D1(r1,r2,r3,…rn)=0 mean “excess demand for output in period 1, which is some function of short term interest rates for the next n periods, =0”

Also D2(r2,r3,r4,…rn+1)=0

And D3(r3,r4,…..rn+2)=0

Etc., from now until the end of time.

So we are looking for some path for interest rates r1,r2,r3….etc. that solves that system of equations.

“Loanable Funds theory”

Are you saying an economy is 100% Loanable funds?

TMF: “Are you saying an economy is 100% Loanable funds?”

No. I don’t even know what that means.

Nick,

Yes, and I am saying that there is no solution.

Nick,

Would it be correct to say that the liquidity preference theory refers to the secondary market for bonds, while the loanable funds theory refers to the primary market for bonds?

rsj: “Yes, and I am saying that there is no solution.”

Never? Sometimes? A corner solution? Discontinuous PPF or I curve? Or not convex/concave?

JoeMac: (“Primary” presumably means “newly-issued, to finance new investment”?) Interesting twist. But I don’t think so. What about the market for output, where newly-produced output is exchanged for money? If LF is new bonds, and LP is old bonds, what about the output market?

I.e. the set of solutions {r_j} that clears excess demand for D1 intersected with the set of solutions {r_j} that clears demand for D2 intersect with the set that clears D_3, etc. can be the empty set.

This is because the rate that sets D_J = 0 is a function of the average of rates, as we are assuming that investment is a function of long term rates.

To see a simple example, let n = 2. Suppose you need the average to be 1% in period 0, 2, 4, .. And you need the average to be 3% in period 1, 3, 5, ..

Then you have:

(1) r_ 0 + r_1 = .02

(2) r_1 + r_2 = .06

(3) r_2 + r_3 = .02

etc.

From (1) we know that

0 <= r_0 <= .02

0 <= r_1 <= .02

From (3) we know that

0 <= r_2 <= .02

0 <= r_3 <= .02

Etc. So we know that all the terms are less than .02 and greater than 0.

But then (2) is impossible to satisfy.

It might be worth putting in giant <blink> tags that (1) if you believe in endogenous money, and (2) that therefore money demand and supply depend on some third factor that itself messes with the real interest rate, then (3) the very first diagram may not represent the locus of points which represent consistent Md, Ms, and r for your pet outlook!

And hopefully that quietens the horde…

rsj: OK. I think I understand. Suppose Summer investment is very productive, and Winter investment is very unproductive. (A period lasts 6 months, and there are only two seasons). And an investment produces output for the following 2 periods. Would something like that work as an example of what you are saying?

A couple of thoughts:

1. I think we might need to look at geometric(?) averages of interest rates?

2. We might get a corner solution with zero (gross) investment in Winter, where all Winter output is consumed.

I might be getting the intuition wrong, but I think rsj‘s identified dynamic inconsistency can be suppressed if the CB conducted price-level path targeting instead. The inconsistency seems to stem from the CB needing to adjust their interest rate ‘again’ after their short-term policy has induced inflation consistent with their long-run target.

Nick’s post said: “TMF: “Are you saying an economy is 100% Loanable funds?”

No. I don’t even know what that means.”

A corporation wants to issue new bonds. Borrowing medium of exchange from an individual saver is what I consider 100% Loanable funds. Borrowing medium of exchange from a bank is NOT what I consider 100% Loanable funds.

Does anybody else get that?

Okay, I’ve probably gotten the intuition wrong. Time to get some paper out.

david: What’s a “blink tag”? (I had to edit my comment, because it came out weird when i put those arrow thingies in??)

TMF: re-read the post where I discuss the relation between the Loanable Funds and Liquidity Preference theories.

rsj: another example: Suppose a nuclear power station, once up and running, keeps on cranking out the same amount of electricity day and night, even though the demand falls at night. Night-time electricity might become a free good, if people are satiated. The 12-hour real interest rate (taking electricity as the numeraire) goes from plus to minus infinity.

Nick,

My understanding is that the IS curve assumes as a default that anything borrowed is automatically spent.

For example, a firm goes into loanable funds and borrows money, and then goes into output market and buys good. When we speak of the IS curve, we first use the loanable funds to explain where it comes from, and then define the curve as being the goods market. It therefore conflates the two processes of the firm. When explaining the IS curve economists do the following. First they show the loanable funds market, then they show how changes there affect the Keynesian cross (output market), and then how that becomes the IS curve.

Technically the loanable funds (primary market) is separate from the goods market. But the IS curve implicitly assumes that any endogenous or exogenous borrowing by firms/households in the loanable funds will be 100% automatically and immediately spent in the goods market as the cross shows. After all, the textbooks always show an immediate jump from loanable funds directly to the KC.

So, when you say “There is an output market where output exchanges for money, and a bond market where bonds exchange for money.” the output market includes the primary bond market and market for goods because it assumes borrowings are always spent on goods.

Or is this all nonsense?

joeMac: what you are saying is not nonsense. But that assumption implicitly underlying the IS curve is deeply problematic.

We can all plan to spend more than our income, not by borrowing, but by planning to reduce our stocks of money. Or we can all plan to spend less than our income, not to lend the excess, but planning to increase our stocks of money. And that’s what causes recessions. We can also all plan to borrow, not to spend, but to increase our stocks of money.

Hehehehehehehehe. M……..M…….

We might not be on the same page. I’m thinking of Loanable funds where people claim borrowing depletes scarce savings and therefore raises the interest rate(s). Is that what you consider the same thing?

Plus, what about borrowing to speculate in financial assets?

Lastly and in the third graph, what happens if the stock of money (I’d rather say medium of exchange) goes down?

Nick,

I have to think about your summer-winter example, but my initial example is “yes, assuming that firms enter into fixed rate nominal debt contracts at the 2 period rate”. And I am thinking that that 2 period rate is the average of the single period rates. I am also assuming perfect foresight, so there is no unanticipated shock or bankruptcy, etc.

If single period volatility is smoothed away in the rolling 2 period average, then the 2 period rate will not be sufficiently responsive to short run changes in investment/savings curves. Over the short run, interest rates are not going to clear the I-S market, but income adjustments will need to clear it. The fact that the rates are an average means that they will always be too high or too low, regardless of how you define average (e.g. weighted arithmetic mean, geometric mean, etc.).

So in your nuclear power plant example, the plant is obligated to make fixed nominal payments out of its profits day and night. That poses a problem if electricity is free at night.

Whereas the social planner might make electricity a free good, the bond markets will not finance the construction of the plant unless it agrees to throw some output away or produce less so that night time sale of electricity earns the same profit as daytime sale of electricity.

Nick,

Just one more question. Are you saying…

1). No, JoeMac, you do not understand IS curve. It is not making that assumption that you describe.

2) Yes, you are absolutely correct. That’s what the IS curve does. But that is a metaphysical problem for reasons X, Y, Z.

Ritwik writes:

#3 and #4 are presented by Bohm-Bawerk in Capital and Interest as two of the three determinates of the interest rate (the third being the uncertainty of the future), and Fisher took the position that his (Fisher’s) Theory of Interest was largely a restatement of the earlier work of Bohm-Bawerk in mathematical terms.

I’m having trouble grasping your point Ritwik and suggest you read: http://www.econlib.org/library/BohmBawerk/bbPTC34.html#Book V,Ch.V

Though perhaps well you need to start earlier in the treatise to have any hope of understanding the phrases employed–being as they are archaic and roundabout to the modern economist…

Nick

1) Not sure what you mean by ‘pure consumption economy where the output of the consumption good is exogenous’, but a Fischer Black economy with no physical capital still has capital – people are doing the producing and all capital is human capital. (Such an economy might be a pure services economy? )The rate of interest is simply the rate of return on that human capital, the capital value is implied in the asset values of the firm(s) in this economy and Y=rK then gives the rate of interest.

A reverse L shaped PPF reduces the interest rate to the subjective time preference – this time preference gives the rate of interest (and hence capital values). The big difference (and this is why ‘finance’ talks past ‘economics’) is that you have to change your frame of reference and begin with the capital values rather than from inter-temporal consumption optimization.

Plus, I am not even sure what the thought experiment of a one-good consumption economy helps us achieve – ostensibly we want a theory of interest in a multi-good multi-asset monetary economy?

2) CAPM is a temporary security price equilibrium, but it can be easily re-framed as a general equilibrium – with more risk-bearing societies being able to generate higher rates of growth. If the only issue is the exogeneity of the risk-free rate to private decision making, here’s my (rather speculative) take on it – imagine a world where the CB did not even bother setting the short rate, but simply announced its price path target/ NGDP target and was perfectly credible. Let’s say that the CB has somehow managed to make money neutral/ super-neutral. This economy would devise a system of repo loans, interest rate swaps, credit default swaps (or other means of splitting out the economic activity of funding from the economic activity of risk taking) and the rate on repo (or other such pure funding) loans would give you the risk-free rate, endogenously. This is my interpretation of the idealized Fischer Black world.

I really think Mehrling’s takes on Black and CAPM are indispensable here, and would request you to read them , if only to ensure that I am not mangling his message.

Click to access revolution_in_finance_and_devt_of_macro.pdf

Click to access understanding_fischer_black.pdf

Additionally, John Geneakopolos and Martin Shubik have re-formulated the CAPM as a GE with incomplete markets on multiple occasions, but I am not invoking them here because I am not sure how they handled the exogeneity of the risk-free rate.

Jon

Say there are (as in Bohm-Bawerk) 3 determinants – time preference, MEC, uncertainty. In my understanding, Irving Fisher modelled the interaction of time preference and MEC, by first abstracting out of uncertainty, and then next including uncertainty but drawing a sharp wedge between capital quantities (‘real capital’) and capital values (asset prices), so that the uncertainty element of interest rates feeds only into prices but not into production.

Let’s say we turn this around – we remove the sharp wedge between capital quantities and prices, see uncertainty as governing the production process itself (rather than just asset prices), and see time preference/ MEC as two ways of stating the same economic fact (and hence always in ‘equilibrium’). Now we’ve arrived at Fisher Black (or so I think).

Oh, and we add that all input is capital, and that there is no better way of understanding the aggregate production process except through asset prices. Then we truly arrive at Fisher Black.

I guess I should acknowledge that in a perfect foresight model it wouldn’t make sense for firms to fund themselves by selling longer period bonds, everyone would fund long term investments by rolling over commercial paper, and no saver would buy fixed rate multi-period bonds, they would all buy short term commercial paper, etc.

Understanding why firms sell long term debt to fund long term investment requires a model with risk, in that firms value knowing what they must pay ahead of time, and this value outweighs (to the individual firm) the possibility that ex-post, they will always be paying more or less than the market clearing rate.

But if we just accept that this is how investments are funded, and if we also accept short run variability in both demand/supply then the above argument should show that in general there is not going to exist a sequence of short term interest rates whose rolling average, however defined, will be exactly the sequence of long term rates that clears investment and savings demands in every period.

I think this is a good case for the Keynesian view that income adjustments are necessary to clear the savings and investment markets, at least for short run variability in investment/savings demands.

Excellent post!

JoeMac: 1.9 😉

Update: what I mean is: there is probably more than one way to rationalise the IS curve. Yours works, but I don’t like it. But maybe all other ways are equally bad.

rsj: people invest in sheep, as long as the sum of the values of wool and mutton exceed the costs of the sheep. But the wool dividend might be worthless. Chickens pay dividends in eggs, meat, and feathers. The feathers might be worth nothing, but the market in chickens can still work.

Switching to general equilibrium, and from different commodities to different dates (all the same in an Arrow-Debreu dated-commodities approach): We can imagine a world where food is the only output, and food is so plentiful in Summer it becomes a free good. You could say there is an excess supply of output in Summer, but it’s not a “Keynesian” excess supply problem. The Keynesian excess supply problem is where the unemployed want to eat, but can’t buy food. Here, it’s satiation.

Let me try it another way: you have specified the “investment” part of the loanable funds model, but you haven’t specified the “saving” part. If we add in the saving part, we could only get your result (of no solution) if people are satiated in consumption during some periods.

Determinant: Are you OK mate?

TMF: Look at the first picture. If the Id curve shifts right, the rate of interest will rise (unless the Sd curve is horizontal).

If I borrow money from another person to buy assets from a third person, that third person might just buy my IOU from the second person. So it’s a wash on net.

It depends on what causes the stock of money to fall; is it a fall in supply or a fall in demand?. If the supply of money falls, the LM curve shifts left. If the demand for money falls, the LM curve shifts right.

Nick,

This is a very good post.

Although, given your enumeration of “the joys of national income accounting”, I’m tempted to ask – is this the same Nick Rowe who used to blog for Worthwhile Canadian Initiative?

“Which is one of the reasons I want us to move away from thinking of monetary policy as setting a rate of interest, even in the short run.”

If “the rate of interest” in question (“natural rate” etc.?) is viewed as a continuously changing rate for a continuously perpetual term, does monetary policy determine (implicitly) the term structure for that rate – as the combination of the policy rate (for some expected term) and a residual perpetual rate? And the policy rate is always overshooting or undershooting and changing everything else in the process as well?

Jon: as you will notice, I carefully avoided using the A-word. My reading of Austrians is like yours: same as Irving Fisher, plus uncertainty, minus the neat diagram. But some Austrians sometimes sound a bit more like 4.

Hmmm. I’m a bit surprised there’s still no riot broken out. The LP and Cambridge UK guys must all be sleeping in. (Or maybe gathering their forces for a massive attack on two fronts.)

JKH: Thanks! I didn’t really want to write it, but I thought it needed to be written. Someone maybe should have written something like this years ago, to stop a lot of unneccessary arguments, so we could concentrate instead on the bits we (at least I) still don’t properly understand (like in my digression, which is where I depart from “mainstream”).

Yep. I was surprised I wrote that bit about NIA too. I nearly censored myself. But it’s a very “subjectivist” joy of NIA. NIA as a tool to help us tighten our intuition.

You lost me a little on the last bit. Let me take a stab at it:

Assume the central bank always gets it right, and everyone knows this. There is a “natural” 1-year rate, that is moving over time. And a natural 2-year rate, that is also moving over time. (And 3 and 4 etc.). If there were no uncertainty, the pure expectations hypothesis would imply that the 2-year rate would be a geometric(?) average of the two 1-year rates. Under uncertainty, and risk-aversion, that won’t work exactly. The central bank can choose any one of those rate (say the 1-year), and try to keep it equal to the natural 1-year rate.

If the central bank gets it wrong, and is expected to maybe get it wrong in future, that will have real effects, and will affect investment, which will affect the future capital stock, which will affect future natural rates, which will affect the current natural long rate,…etc.

Nick,

Let me play that back in terms of the relationship between natural and actual, and the feedback between the effect of the difference between the two on real activity, with further effect on natural rates.

There is an actual yield curve (and BTW an actual curve of implied forward rates for all terms based on that actual yield curve).

Suppose there is a natural yield curve (and BTW with a natural curve of implied forward rates for all terms based on that natural yield curve).

(The forward rates are a by product in both cases, not really necessary to the discussion.)

The CB sets an actual policy rate, say the ON rate.

That actual ON rate need not be the same as the natural ON rate.

And therefore there is nothing to say that any corresponding points between actual and natural yield curves or between any set of actual and natural forward rate curves be equal.

And deviations will have real effects with consequences for the natural curve itself, with knock on deviations between actual and natural, etc. etc.

IF the actual ON rate deviates from the natural ON rate, then the actual ON rate perturbs the natural yield curve into an actual yield curve which is not the same, and which has real effects with further consequences for the natural curve.

Would a natural curve have a slope?

Or would it be optimized to a uniform perpetual rate?

JKH

That is very similar to my favoured way of thinking about natural and market (actual) rates, which I specified in a comment on some other post by Nick. Suppose that we reduce the yield curve into only two assets – money and bonds. Now there are four rates of interest which we want to talk about : money-natural, money-actual, bond-natural, bond-actual.

The CB only sets money-actual. It could fail to move bond-actual. Or, it could fail to clear money-natural at the money-actual rate that it sets.

The most perverse developments happen when the CB ‘manages’ to make bond-actual clear with bond-natural, without making the money rates clear. We see macroeconomic stability, low unemployment, low inflation, stable NGDP etc. All this while, money-natural can drop a lot and diverge significantly from money-actual, creating a massive increase in money demand because of the simple arbitrage of investing in money-actual. Because the macroeconomy is stabilized, nobody realizes/ bothers about this money demand that is increasing in the background. A entire industry sustains itself on finding new ways to service this money demand. Then, one day, s*it hits the fan and everybody re-discovers their favourite theories of the recession – shortage of safe assets, negative real rates, money demand, NGDP shock etc.

The one big leading indicator in all of this is what Raghu Rajan had been warning about since about ’05-06, the ongoing dearth of fixed investment/ hard assets.

JKH @9.48: Yep. Agreed.

JKH @9.56. In principle, the natural yield curve could slope either way, and change slope over time. E.g. demographic changes, which people see coming, will change the ratios of middle-aged savers to young and old dissavers, so the natural short rate will be expected to change over time, and the slope of the yield curve will change with it. Or it could be anything else, not just demographics. In general the (real) interest rate is a relative price of two goods (claims on future apples vs current apples), and relative prices will change over time when supply and demand (tastes, technology, resources) change over time. Only under very special assumptions will relative prices not change over time, and you get a flat (real) yield curve. In principle, there must be a monetary policy that would give you a flat nominal yield curve, since monetary policy can (in principle) make the price level do whatever it wants, so by getting inflation and expected inflation to change by just the right amount at just the right time, the BoC could covert a fluctuating sloping real yield curve into a flat nominal yield curve. (I’m not thinking Operation Twist here.)

Nick, what theory underlies the view that an asset’s interest rate (or own-rate. ie. expected rate of price appreciation) is one component of the expected return that said asset must provide in order to be held? … and that after adjusting for risk and liquidity, all asset yields equal out via arbitrage? Is this Fisher + liquidity preference?

JP: I see that as very different. Loanable funds is a theory of “the” interest rate. And it can be used to figure out a theory of the time-path of “the” interest rate. Same with Liquidity Preference, which is also a theory of “the” interest rate. For interest rate differentials across different assets, Arrow-Debreu implicitly contains a theory of all real interest rates. Any asset is just a bundle of Arrow-Debreu commodities. But since it’s a world with zero transactions costs and complete markets, I’m not sure how far I would push it.

Nick,

I’m sorry, I don’t understand your sheep example. In general, the effect that I am talking about has nothing to do with corner cases, it is the general case. The CB is trying to solve an infinite tower of optimization problems, subject to the constraint that all but the first of the short rates used to solve each problem must also be used to solve the problem below it. When I say that there is no solution that simultaneously solves all problems, it is not because the solution to each individual optimization problem must correspond to a special solution of the underlying problem.

Think of it this way — We are in a coffee-shop economy. And coffee shop owners will not build out a store if they can only secure a month to month lease. They prefer a 10 year lease, with fixed payments. Similarly, owners of land prefer to give a 10 year lease. If those rental payments correspond to the 10 year geometric average of gross rates, which is roughly the 10 year arithmetic average of rates, then in half the periods you would expect the short rate to be lower, and in half the periods the short rate is higher. When the central bank lowers the short rate, the capital rental rate remains higher, and when the central bank raises the short rate, the capital rental rate remains lower.

Now the question is, if the CB knows what the market clearing sequence of rental rates will be each period, can it target the short rate so that the rolling average is the pre-scribed sequence? The answer, in the general case, is no. Demand to rent coffee shop space may be low in even periods, and high in odd periods. But as 10 year leases are being signed, the rental payments will reflect the average demand, not the spot demand. To the spot market, it will appear as if the rent rates on offer are “stuck”, in that they are not responding to the demand for spot rentals. In reality, the landlord would rather let the space sit empty and wait for one period until demand is higher, rather than get a lower payment for 10 years because they need to rent the space out now in order for the spot market to clear.

None of the above has anything to do with satiation, corner cases, discontinuous preferences, etc. This is an argument based on incomplete markets.