Imagine a world where education is of no intrinsic value, and serves only as a signal of an unobservable character trait called "ability." Performance (which can be observed) is determined by both ability and effort. Effort is costly. Some students have a high level of ability, and some have a low level of ability. A professor's job is to rank them. Professors cannot recognize absolute excellence, only relative excellence, and so grade on a curve.

To keep things simple, imagine there are just two students, a high ability student, Alice, and a moderate ability student, Betty. The professor will always give out one A and one B.

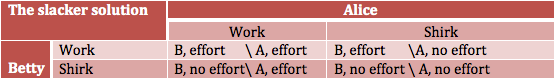

The optimal strategy for the students depends upon their relative ability. Suppose that Alice's ability so much exceeds Betty's that she will always does best, no matter how hard Betty studies, and how little Alice does, as shown in the table below:

The first part of each cell describes Betty's outcome, and the second Alice's. So, for example, when both work, Betty's outcome is (B, effort) and Alice's outcome is (A, effort). In this scenario, Alice's superior ability means that the relative performance of the students is unaffected by studying, so there is no point in either of them putting out any effort. We arrive at the slacker solution.

The professor might complain about his students' shirking, but he would be wrong to do so. The students are shirking because mastery of the course material is not of intrinsic value to them. Since the purpose of education is to signal ability, coordinated shirking is a good thing, because it allows students to transmit an accurate signal of their ability at a lower cost.

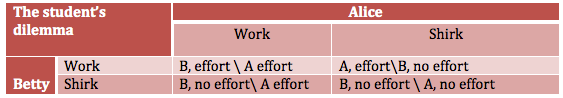

The more interesting game is the student's dilemma. In this game, if Betty works and Alice shirks, Betty can outperform Alice.

The outcome of this game depends upon how the two students value effort and grades. There are three possible scenarios.

If Betty would rather get a B than study, so she prefers (B, no effort) to (A, effort), the optimal strategy for both is to shirk. If Betty is shirking, there is no point in Alice working, because she can get an A without studying. If Alice is shirking, Betty could achieve an A by working, but it's not worth it to her, because the cost of studying is greater than the benefits of an A. The slackers' equilibrium will prevail unless Alice actually gets positive enjoyment from studying. As long as Betty is shirking, there is no point in Alice ever working, as she will get an A regardless.

If the cost of effort is low enough (or the value of grades high enough) that both Alice and Betty would rather study than settle for a B, the game has no pure strategy equilibrium. If both start off shirking, Betty has an incentive to start working, because she can get an A rather than a B. But if Betty works, Alice has an incentive to work too. However, if Betty figures that Alice is going to work, there's no point in her working, so she shirks. Yet, if Betty shirks, then Alice figures she might as well too. We have the students' dilemma.

A final possibility is that, perhaps because Alice has attention deficit disorder, the cost of studying is lower for Betty than Alice. Betty prefers (A, effort) to (B, no effort), but Alice prefers (B, no effort) to (A, effort). They can both get what they want when Betty works and Alice shirks. This is an equilibrium because, if Betty is working, Alice doesn't bother, because she would rather settle for a B than put in the time and effort to get an A. If Alice isn't working, Betty does, in order to get a solid grade.

In this final scenario, when Betty works and Alice doesn't, the usefulness of education as a signal is restored. However it no longer serves as a signal of innate ability. Instead, it signals the cost to an individual of exerting effort. Those who get As are those are able to get organized, study, and hand things in on time at a low personal cost, and thus are likely to be able to get organized and hand things in on time in the workplace also. This, from an employer's point of view, is as good a reason as any to hire someone with a university degree.

The picture presented here is a caricature of education. In the real world, grades are determined by both relative and absolute performance. Yet, when relative performance matters, there is always the possibility of the student's dilemma.

A good part of the workplace is exactly the same: part of your work and part of your evaluation ( not always the same %) is absolute performance with your boss not knowing both your potential in fulfilling the task and the possibilities that were available, part of your task relative , part totally random.

All in all, the education system is tasked at giving you training in using your abilities as well as teaching how the system work.

Jacques Rene – “All in all, the education system is tasked [with] teaching how the system work”

This, I think, is one of the greatest benefits of going to public school rather than private school. Public school is a pretty good lesson in how life works. Private schools, to the extent that they have the philosophy “our job is to make you happy, the customer is always right, and we will make you succeed in life”, are not such a good preparation for the real world.

Public schools do prepare us for the life of middle-class mid-echelon grinds who makes the world turn ( with the help of the working class whose being directed by us is our perk.).

Private schools , if we understand high-end one such as UCC, prepare you for a world where you’re always right and everybody else is your always admiring sycophantic underling. Magnificent preparation for your upper-class role. ( Of course after a few generations, you are ripe for a lunch date with the business end of the guillotine or in its modern western benign form, losing the presidential election and blaming it on the moochers.)

A bit like the difference between military college and ROTC…

.

Jacques Rene – my thoughts on that might be better left unsaid!

COTC is what we have in Canada, I knew a few friends who were taking that plan. RMC accepts anyone, I don’t think we have a “military class” in Canada that sends it offspring to RMC generation after generation. We’re just too small and too cheap for that.

I knew I should have held out for private school. I just never know what to do with my sycophantic underlings.

“RMC accepts anyone” yes, provided they meet its rather demanding entrance criteria.

There is something of a military class in Canada – it was interesting to learn how many of my brother’s classmates were the sons or daughters (but typically sons) of military men. But, by virtue of our small military, it is inherently small. Then again, I suppose the same proportion of law students or med students are the sons and daughters of lawyers and doctors.

This is valid beyond the world of education and it is valid to any area where information asymmetry plays larger role. Such areas can be identified as ones dominated by consumer tests where alleged proffesionals set their own criteria to select a “winner”. In such areas firms don’t have to do the “best” they can be in absolute terms, they just have to be better than their competitors. And even here they don’t have to be the best at what they actually offer to customers, they just have to be the best at the test. And that is many times something completely different.

Determinant: in my own times,when I wanted to enlist at CMR St-Jean and RMC Royal Roads with the goal of becoming a carrier pilot, ( I am so old that I remember when the CN had a carrier), it was ROTC. I am not losing memeory, I simply have old ones…

theoretically the equillibrium in case of the low cost for shirking would be that Alice will work some percentage of the time to make Betty indifferent to work and vice versa, so that the solution is always on the edge.

Makrointelligenz – yes, you notice that I said “there is no pure strategy equilibrium.” A mixed strategy equilibrium is definitely a possibility.

Determinant: in my own times,when I wanted to enlist at CMR St-Jean and RMC Royal Roads with the goal of becoming a carrier pilot, ( I am so old that I remember when the CN had a carrier), it was ROTC. I am not losing memeory, I simply have old ones…

Yes, HMCS Bonaventure. I came across a book on it in my town’s public library, as any 14 year old boy would when browsing the military section.

I then went to a job interview with a recruiter who had a picture of it on the wall. I asked it that was the Bonaventure, and his eyes lit up. He asked how I knew, I said I saw the book. I had him eating out of the palm of my hand.

Then I went to the actual company and they cancelled the job right there in the interview. It was a very weird day.

They call it COTC now. Somebody may have done a branding exercise a few years back.

@ Frances: Yes, i did not mean to imply that you were wrong. It was just a thought that came immediately to my mind as i have been thinking about game theory a lot and as I am one of those lazy guys I just wrote it down without any explanation ;).

Makrointelligenz – I figured there was probably a mixed strategy equilibrium, and was just hoping that someone would explain the mixed strategy equilibrium in the comments!

I thought you were going to discuss a real dilemma. As in, what skills should US students pay $200,000 to acquire in order to have a stable middle class future. With surging imports and unstable economic policies, it is silly for most US students to invest in skills because the industry-specific skills they acquire will be useless if the industry dies. A case in point is aerospace. Boeing will probably die or be bought off in the next five years, so it would be a shame for any American to pay to study aerospace engineering. Those jobs will be in China, or in Europe, and he will be out $100 k with nothing to show for it but non-dischargeable debt.

John – I agree with you that there are serious issues about how well students are served by universities both in the US and in Canada (though the US situation differs from the Canadian one in important respects). This isn’t something I like to blog about, but it is something that, over the next three years, I’ll be working on internally at Carleton.

John, Frances: if we want mobility, either geographically or professionnaly, we will have to face a reality: everything that smacks of infrastructure should be somehow “publicly” “owned” ( quote marks around both terms as it does not necessarily means government provided.

But in the same wat that there are public faucets, there should be universal wi-fi (and even some ) phone access.

The concept of “owning your home” make no sense if you want a mobile workforce as it means investing your own capital in risky asset. Same for education. If you want society at large to benefit from professional mobility, society should shoulder the costs.

Moreover, asking an 18-year old to make a forecast of what the economy’s requirement will be for the next 40 year while no sane economist would dare make one ( unless he is very well-paid…or work at IEA where they forecast the oil market in 2050… oh yeah they are well-paid)), is insane.

So: tuition is free but stiff success requirements. Housing is publicly provided but you pay rent covering the cost. Or something to be worked out.

But we have to stop modeling our society as if we were hunter-gatherers or medieval turnip growers who never go farther away than two kilometres from their birth mud hut.

In case of the mixed equilibrium, it depends on costs and benefits how often each person will shirk or work. Lets say the cost of work is 1 for both and the benefit of getting an A compared to B is 2 for both. Then Alice will work 50% to make Betty indifferent to work (working will lead to -1 and +1 50 % of the time) and Betty will work 50% to make Alice indifferent (working will lead to +1 50% of the time, -1 50% of the time). When the benefit for Alice is bigger c.p., Betty will work less often while Alice will keeping working the same.