Smaug the dragon is typically viewed as a fiscal phenomenon, depressing economic activity by burning woods and fields, killing warriors, eating young maidens, and creating general waste and destruction. Yet peoples – whether elvish, dwarvish, or human – have considerable capacity to rebuild. Why did the coming of Smaug lead to a prolonged downturn in economic activity, rather than a short downturn followed by a period of rebuilding and growth?

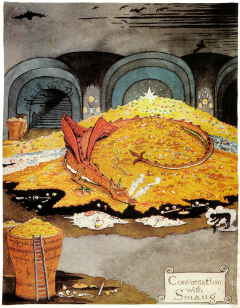

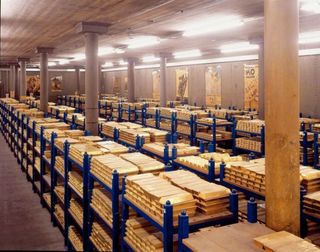

The full economic impact of Smaug can only be understood by recognizing that the dragon's arrival resulted in a severe monetary shock. On the left is shown Smaug's hoard. On the right, for purposes of comparison, are the gold reserves of the Bank of England. It is clear from a simple inspection of these two figures that the amount of gold coinage Smaug withdrew from circulation represents a significant volume of currency. This would, inevitably, lead to deflation and depressed economic activity.

The full economic impact of Smaug can only be understood by recognizing that the dragon's arrival resulted in a severe monetary shock. On the left is shown Smaug's hoard. On the right, for purposes of comparison, are the gold reserves of the Bank of England. It is clear from a simple inspection of these two figures that the amount of gold coinage Smaug withdrew from circulation represents a significant volume of currency. This would, inevitably, lead to deflation and depressed economic activity.

The interpretation of dragons as monetary phenomena is supported by the events occuring after the death of Smaug. Upon the great worm's demise, the wealth it had stockpiled was shared between the dwarves and others who had contributed to the fight. Much gold was sent to the Master of Lake-town; followers and friends were rewarded freely. The result was an immediate increase in the money supply, and a rapid growth in overall economic activity.

One has to ask whether or not a more innovative monetary policy framework could have ameliorated the impacts of the dragon-induced economic downturn. If the peoples of Middle Earth had abandoned their gold specie standard, and switched instead to a paper currency, they could have revived trade-flows without sacrificing so many lives. Unfortunately, the lack of a central bank, or indeed any but the most rudimentary monetary institutions, was a major obstacle to currency reform.

Dragons come. The question is how to respond to them.

Considering that Smaug actually took over the castle some 150 years before “The Hobbit” takes place, would not price rigidities have resolved themselves and economic production returned to pre-Smaug levels?

On the other hand, I suppose if Smaug had continued to ravage the countryside year after year, perhaps the money supply was continually decreasing. Fully downwardly rigid nominal prices (like for debt, or if social standards hadn’t adjusted, for wages) could then prevent economic adjustment.

But then again, just to continue the argument, it seems unlikely that prices would be very sticky at all in a feudal economy. The two stickiest prices, wages and debts, probably didn’t exist. Most workers are subsistence farm owners and are not paid wages. The financial system is negligible – if it even exists – making debt contracts rare. While there certainly could be some sticky prices, those are adjusted over time with much more ease than wages or debts, no?

If this were the case Smaug’s deflationary actions would be purely nominal and all his real effects would be through the “fiscal policy” you mention.

What did Smaug want with the gold? Did he plan to trade it for dragon food or other goods and services? Did he plan to leverage it to gain power or status?

From what I understand from the movie (part I), Smaug just sat on it. So, was he just trying to disrupt the dwarvian economy?

Are dragons mortal? If so, he’d probably never spend it. Did he just want it for the consumption value of owning it? Did he want it just to feel rich?

Basil H – you raise many serious and thought-provoking questions.

If Smaug had only removed some coins from circulation then, yes, over time the economy should have been able to adjust through price deflation. However if Smaug removed the vast bulk of the money supply, and the lack of dwarves under the mountain meant that no additional coins were being made (see http://mortonandgeorge.wordpress.com/2012/12/20/central-banking-in-middle-earth-or-the-much-maligned-king-thror/ for an insightful analysis of the role of dwarves in Middle Earthian banking.) At this point, there could have been insufficient coinage to conduct basic transactions. Once money fails to fulfil its role as a facilitator of transactions, it is hard to undertake economic activity.

I’m also not 100% convinced by the characterization of Middle Earth as feudal. The Shire, for example, was clearly not organized on feudal lines. Moreover, even thought it had feudal elements, there was – pre-dragon – a clear division of labour, as well as trade, between men and dwarves, and also between men and elves (think of the barrels going back and forth up- and down- river between men and elves). It is the diminishment of this trade – a return to autarky – that is the chief harm caused by the dragon.

Phil – Dragons just like gold – they’re greedy and avaricious, and like to sit upon their wealth. So one can think of this not only as a monetary shock, but as the diversion of wealth from potentially productive investments (an improved road through Mirkwood, for example), to unproductive uses (being sat on by dragons).

Smaug could continue to exert depressive forces on commerce for 150 years because of the fear of confiscation. This might have been offset if he ever intended to use the gold but he did not. Marginal tax rates were therefore close to 100%.

Frances,

“It is clear from a simple inspection of these two figures that the amount of gold coinage Smaug withdrew from circulation represents a significant volume of currency. This would, inevitably, lead to deflation and depressed economic activity.”

This would lead to depressed economic activity IF the velocity of the remaining gold coinage within the economy did not increase to offset the removal of coinage by the dragon.

This would lead to deflation IF the amount of goods produced in a time period remained the same while the demand for those goods fell.

To say that both deflation AND depressed economic activity would happen, you have to allow for either sticky prices OR you would have to say the the remaining gold coinage was not infinitely divisible.

Suppose before the dragon, there were 1 million one ounce gold coins circulating through the economy. Suppose the dragon withdraws 500,000 of those coins from circulation. If the velocity of the remaining gold coinage does not double, you will see a reduction in economic activity. Suppose the same amount of goods were produced but the demand for those goods fell by half. The price of those goods would have to fall by half for all goods to be sold.

BUT, suppose that the remaining coinage was not divisible and still recognized as coinage. A person could not take his one ounce coins, cut them in half, and pay for goods in 1/2 ounce increments.

That is the magic that paper denominated currencies provide, they are divisible to any degree you would want.

Frank –

Sticky prices or not infinitely divisible coinage both seem potentially reasonable explanations – despite Basil H’s arguments on the implausibility of sticky prices playing a significant role in a subsistence economy.

Unfortunately there are almost no references to prices anywhere in the Hobbit. The four references to “price” include two to “beyond price” and one to “fair price.” There are no references to wage, salary or income, but seven to reward. There are 15 references to wealth, 41 to gold, one reference to coins (“pots full of gold coins”), 22 to silver, 4 to trade, and 3 to exchange. No mention of cost to speak of.

So there is little archival material which we can draw upon to prove or disprove the sticky prices theory.

Robert, fear of confiscation would certainly mitigate against the accumulation of gold and other forms of wealth. To the extent that dragons covet paper currency less than gold, this would be another reason why a move away from a gold specie standard would have been highly desirable.

Frank: Given that the main economic impact from the dragon was trade between different species, do you think it could have been possible to establish a currency without inherent scarcity, such as a commodity? Such a feat requires a central bank with universally recognized authority. But what would have motivated Men, Dwarves and Elves to recognize the same authority when it would undermine their ability to self-govern?

Is it even possible for two completely different sentient species to utilize a single currency without a single government? I think that’s a serious question that we have no way of answering until we encounter another species with economic trade.

Jordan,

“Frank: Given that the main economic impact from the dragon was trade between different species, do you think it could have been possible to establish a currency without inherent scarcity, such as a commodity?”

Scarcity can be a physical property, it can be completely contrived, or it can be some combination of the two. I believe the races could have come up with a currency whose scarcity was not entirely a physical property.

“Such a feat requires a central bank with universally recognized authority.”

Not exactly. It requires an authority to define a uniform set of measurements for the quantity of the medium being used. It would also require a storage and release mechanism for the medium being used. But that medium does not have to originate within a banking construct.

Imagine if we discovered a species in a far away solar system that conducted monetary transactions through the transfer of energy from one storage mechanism to another and finally to end use. “Banks” would still serve as storage points for the medium. There would still be a unifying definition of what constitutes a kilowatt-hour, or Joule, or whatever unit of energy this species uses. But the medium itself would be created outside of a central banking paradigm.

Jordan:

” do you think it could have been possible to establish a currency without inherent scarcity, such as a commodity? Such a feat requires a central bank with universally recognized authority”

I’m not sure that “inherent scarcity” is the right term for the idea you’re getting at. Any resource with a price greater than zero is a scarce resource. I do know what you mean, however – it’s the difference between a currency like gold and a currency like cowrie shells or goats. Nick Rowe or Stephen Gordon would know the precise term.

As to what would have motivated men, elves and dwarves to recognize a common central bank – it’s worth giving up some sovereignty for increased economic prosperity.

Frank – yes.

Frances,

Don’t you mean any resource with a value greater than zero is a scarce resource? Price is a method of determining the market value of some resource when it is bought and sold and depends on some construct of ownership (legally maintained or otherwise). But ownership can be transferred in non-market oriented ways (force of will, charity, inheritance, etc.).

Frank: “Don’t you mean any resource with a value greater than zero is a scarce resource?”

No. The air we breathe has value, but it doesn’t have a price, because there is no scarcity of air for breathing (if we want the atmosphere to absorb massive amounts of pollutants then, yes, there are scarcity issues, but not when it comes to air for breathing).

Price is generally determined by what happens on the margin. Value is infra-marginal.

Frances,

Price is determined in a market based economy, goods are traded for other goods (relative prices) or for some recognized medium of exchange. I am talking about communal economies. In economies such as these there are no prices because there is no trade. All goods still have value whether they are rare or abundant, but that value is a function of the benefit that the good provides (utilitarian or otherwise).

And so in communal economies, there are no prices for goods but goods can still be scarce depending on how many of those goods are demanded versus how many of those goods can be produced.

Oh my Dear Sir. You have completely missed who Smaug is in this instance…and mistaken the Dragon himself as the professed bringer of plenty. In short the very Central Bank and it’s combustible paper.

Dragons are collectors, the collecting and the collection are the point. Though collectors do often think the value is the point, it is not.

You are not to forget that it was not only money that was lost, but jobs were also lost. Suddenly all the workers in the mine was without job. And that that was the core of their economy and the ability to collect benefits would not be possible thanks to the of their federal reserve.

Btw, they are to be seen as refugees as they fled out of the their halls and mass unemployment are in refugee camps common, even after a long period.

“If the peoples of Middle Earth had abandoned their gold specie standard, and switched instead to a paper currency, they could have revived trade-flows without sacrificing so many lives.”

What if they switched to a medium of exchange that was all demand deposits and no currency?

kekonius – Eric Crampton takes this position in his lengthy response on Offsetting Behaviour – see http://offsettingbehaviour.blogspot.ca/2012/12/best-not-to-leave-live-dragon-out-of.html. I respond to him as follows: While not denying the impacts of dragon invasion on the real economy, I maintain that the monetary angle is both important and underappreciated. According to the World Gold Council (quoted in Wikipedia) “all the gold ever mined totaled 165,000 tonnes.[2] This can be represented by a cube with an edge length of about 20.28 meters.” Over half of that has been mined since 1950. Compare the picture of Smaug’s pile pictured in the Hobbit (and my post) with a 20 metre square cube – Smaug’s pile is significant relative to total global historical gold production. It’s hard to believe that this would not have caused a serious monetary shock in an economy using gold for coins.

Too Much Fed – paper currency could, potentially, be subject to dragon incineration, so I can see the advantages of demand deposits or other more sophisticated monetary instruments. However I’m not sure that the monetary institutions of middle earth were sufficiently sophisticated to handle a demand deposit system.

Kekonius – The workers weren’t just without a job – they were eaten by the Dragon. A monetary push has a harder time fixing that.

Why do men/elves/dwarves need a common currency? Why can’t each country come up with its own currency, and have a freely floating exchange rate?

In think the focus on the fiscal/monetary distinction misses an important point. Smaug ate the confidence fairy.

kharris – like it!

Alex: “Why do men/elves/dwarves need a common currency? Why can’t each country come up with its own currency, and have a freely floating exchange rate?”

Hmm. Maybe it’s because men/elves/dwarves have very different comparative advantages, and since they all live intermingled transportation costs are as low between dwarf and elf as between elf and elf, so that there is more trade across men/elf/dwarf lines than within each group? If so, Middle Earth would be an Optimal Currency Area, unlike the Eurozone. (BTW, who, if anyone, acts as lender of last resort in Middle Earth? Or don’t they need one, because there is such a small financial sector?)

The mine under Erebor was producing vast amounts of gold, which must have caused terrible inflation in Middle Earth’s money supply, redistributing purchasing power to the Dwarves from everyone else. Moreover, the Dwarves didn’t create the gold by their own labor, so most of the benefit they received from mining it was an untaxed land rent. Until Smaug came along the Dwarves were running Middle Earth like a petro-state. By shutting down the mine, Smaug halted the runaway inflation and overthrew the tyrannical Dwarven Monarchy.

Is “Smaug” an Austrian name? Just asking.

There are a couple of things about Smaug’s monetary policy that Market Monetarists (among others) would emphasise: it’s not just Smaug’s current monetary policy that matters, it’s his expected future monetary policy too. It’s not just the current pile of gold he’s sitting on, it’s the expected future pile of gold he will be sitting on. And Smaug’s future monetary policy is likely to be deflationary. Plus it’s very uncertain. We know a lot about Smaug’s monetary policy instrument (grab gold, and sit on it). But we know next to nothing about Smaug’s monetary policy target.

Nick – actually, it is (from Wikipedia) Tolkien noted that “the dragon bears as name—a pseudonym—the past tense of the primitive Germanic verb smugan, to squeeze through a hole: a low philological jest.”

Philological jest or subtle reference to Austrian monetary theory?

Nick,

“We know a lot about Smaug’s monetary policy instrument (grab gold, and sit on it). But we know next to nothing about Smaug’s monetary policy target.”

But we can venture a good guess on the motives of Smaug’s monetary policy. Smaug does not engage in trade that would require a medium of exchange such as gold coins, so my bet would be that he is using his monetary stance as bait to lure food.

If the people of the shire would submit themselves to ritual sacrifice, then the dragon no longer requires gold to obtain food.

Frances: does it help that a reliable source estimates Smaug’s holdings at $62 billion?

The biggest puzzle in all this, as Basil H notes in the first comment, is why didn’t prices adjust? 150 years is surely long enough for prices to adjust to the new monetary regime.

I now have the answer to that puzzle. It’s obvious, once you think of it. It is known in macroeconomics (and in finance) as the “Peso Problem”.

It is obvious that Smaug’s monetary policy has a high variance. But what is less obvious, and more important, is that the probability distribution defined by Smaug’s monetary policy is highly skewed, with a very fat tail on one end. Rather like Smaug himself. Specifically, there is a very small but nevertheless non-zero probability of a very large change in the monetary regime. Somebody might kill Smaug, release the hoarded gold into circulation, and equally importantly, stop Smaug grabbing more money in future. If it happened, that would cause a very large increase in the equilibrium price level P*.

Now, suppose you are a New Keynesian firm on middle earth, and the Calvo fairy has by chance landed on your shoulder, tapped you with her wand, and given you permission to change your price. You know there is a 99% chance that Smaug will continue his monetary regime, so P* will stay low, so you want to cut your price to P* (I’m ignoring strategic complementarity in price setting for simplicity). But you also know there is a 1% chance that Smaug’s regime will end, and P* will increase massively, before the Calvo fairy visits you again. Assuming linearity, and a symmetric Nash equilibrium, you will set your price at Pi = 0.99(P/Smaug continues to hoard) + 0.01(P/Smaug’s regime ends). So you will set your price strictly above the P* conditional on Smaug’s regime continuing. And since all firms do the same, P > P*, and there will be a recession as long as Smaug’s regime lasts. Even if it lasts indefinitely, as long as there is a non-zero probability it will end suddenly. And a massive (inflationary) boom when it ends.

What we are observing in Middle Earth is a failure of prices to adjust to equilibrium despite fully rational expectations. Because we do not observe the infinitely long sample that would be required to observe P=P* on average, because P* has a fat tail.

Frances: Help! I just wrote a long and very good (IMHO) comment, and Smaug (or someone) put it into spam. Can you fish it out please?

Nick – awesome comment. Some dark and evil wizard must have put it in the spam.

Smugan is from the same family as smuggling.

Smaug also eats young maiden ( a total waste of a precious resource). What are the effects on the labor force?

Nick,

I don’t think the 1% chance applies to the end of the Smaug regime. I think it applies to you knowing the point at which the Smaug regime ends. If you are situated close to where Smaug has chosen residence you would set your price closer to P*, where as if you lived far away from Smaug you would set your price much higher than P*, knowing that it might take years before the information that Smaug has been killed ever reaches you.

From a trade flow perspective, those who live close to Smaug would gain a trade benefit from superior access to information while those living far away from Smaug would be disadvantaged.

Thanks Frances! Hmmm. I have been vaguely wondering if something similar might be going on in the US and UK and Japanese economies. Why isn’t there more deflation/disinflation? Because there’s a skewed distribution, with a fat tail, with a small probability of high inflation coming out of the recession? Must think more, and maybe do a post on this.

Frank: maybe, but the question is whether the flow of information is faster or slower than the speed at which prices adjust?

The issue was that Smaug acted to greatly reduce the real return to investment. Dwarves left the plentiful mines in Erebor, and the specialization no longer was an option for men and elves. Braindrain would also have been a problem. This is in contrast to ww2 for example, when destruction of physical and human capital created significant investment opportunities.

yoyo- I agree that Smaug’s coming had impacts on the real economy. Yet focussing only on these real changes, while ignoring Smaug’s role in monetary policy, leads to an incomplete understanding of the complex macroeconomic dynamics of Middle Earth.

Via @keithjs on twitter, an interesting post on Tolkien’s views on economics: http://www.alternet.org/speakeasy/2010/06/18/what-would-frodo-do-jrr-tolkien-and-political-economy

Dwarves’ mining gold to use as a medium of exchange or store of value is a waste of scarce resources (assuming those Dwarves’ labour had an opportunity cost). Given the quantity theory of money, half the amount of gold, at double the value per ounce, could do exactly the same job. So Smaug’s causing the dwarves to leave the gold mines would create a net benefit to Middle Earth (if it didn’t cause a recession) because it allowed their labour to be transferred to productive uses. Gold mining is just rent-seeking (aside from industrial uses of gold, where the number of ounces is what counts to fix your teeth). The gold miners get the benefit, equal at the margin to the alternative value of their time, but anyone holding gold suffers an equal loss, from the inflation tax. But measured real GDP would fall if the dwarves left the gold mine, because the rents from the mine (which were counted in GDP even though there was no contribution to welfare) would disappear.

Nick,

Price for person living near Smaug, 100% chance that person will know Smaug’s current status:

P = 100% * P1 – If Smaug alive

P = 100% * P2 – If Smaug dead

Price for person living far away from Smaug, 1% chance that person will know Smaug is dead:

P = 99% * P1 + 1% * P2

P1 = Current low price

P2 = Adjusted price with knowledge of Smaug’s death

While the dragon exists, prices for the person living far away will be set higher than those living close to the dragon. This should result in a trade surplus for the people living close to the dragon and a trade deficit for the people living far away from the dragon. When the dragon is killed, the price adjustment occurs first for people that live close to the dragon reversing the trade surplus.

Nick,

Fat tails are worth studying, Consider what is involved in investing in a market with infinite variance. As with the death of Smaug, you have a very low probability of a shock against which you can’t hedge. We don’t deal with this kind of thing very well.

If you look at Smaug as an unavoidable trading partner, what would you expect his response to be to your debasing your currency?

@Frank Restly: ” In economies such as these there are no prices because there is no trade.”

The price of a good is what you sacrifice to get it. All scarce goods will have prices even in a communal economy, e.g., the time sacrificed to hunt a deer is the price of the deer.

I see the Smaug problem as a local issue for the residents in the neigborhood of the lonely mountain.

Certainly, after Smaug moves in, confiscates the dwarven gold and shuts down the gold mines of Erebor, the men of Laketown could attempt to introduce a fiat currency. Perhaps they could create some monitary stimulus that may unlock the local economy to some degree. But, would the other realms of Middle Earth accept Laketown scrip?

They are still going to have to trade what little gold they have with the merchants that trade with the Shire to buy any imported goods. Or, they would be net exporters for some time until they rebuilt their monetary base.

Gene,

“The price of a good is what you sacrifice to get it.”

I presume that you consider your lifetime on earth a scarce resource? What did you sacrifice to get it?

“All scarce goods will have prices even in a communal economy, e.g., the time sacrificed to hunt a deer is the price of the deer.”

The cost of the deer is the calories expended, time used, plus whatever injuries may be incurred in tracking and felling the deer. Price is arrived at through a mutual agreement between two parties engaged in trade. Costs can be incurred by a single individual without a trade taking place – lightning strikes the deer hunter costing him his life.

Gene,

We may just be arguing over semantics here, but in my mind price is agreed upon by two parties, cost can be incurred by a single party, and value can be determined by the needs / wants of a single party.

Re: the monetary impact of dragons.

I seem to remember reading somewhere that when Alexander the Great possessed himself of the Persian capitals, he found large amounts of gold, gems, etc. He proceeded to spend heavily, releasing large amounts of specie into circulation. Does anybody have a reference on this, did it actually happen, what were the results, etc.?

Cross-posted from Economist’s View (Links for 31/12)

Perhaps putting the Coming of Smaug into the historical context will help.

The dragon forced the dwarves of Erebor to flee with nothing more than they could carry. Some fled to the Iron Mountains to live under Dain others relocated to the Blue Mountains west of the Shire. About 30 years later Thror attempted to retake Moria. His death triggered a nasty war with the orcs in Moria, who had killed Thror. This was a war of vengeance and ended when Dain slew Azog at the Gates of Moria. He also saw something worse than orcs inside the Gates of Moria so the majority of the dwarves chose not to assist Thrain in retaking Moria. After that Thrain and Thorin returned to the Blue Mountains for many years where they prospered somewhat, but only slowly built up their wealth. When Thrain was old he set out for the Wilderlands, possibly with the idea of making an attempt on Erebor, but was captured by Sauron and tortured to death. This was when Gandalf received the key and map of Erebor, which he later gave to Thorin.

Smaug also destroyed the town of Dale, which was at the foot of Erebor. The survivors of Dale fled to the great lake and founded Lake Town and they weren’t able to bring most of their goods or tools with them. Eventually they were able to (re)establish trade in wine with the Elves of Mirkwood and were probably engaged in trade with the Dwarves of the Iron Hills and, maybe, the Blue Mountains.

Additionally there were other problems in the area. The Necromancer (Sauron) was significantly limiting trade west through Mirkwood and south with Rohan and Gondor. The increasing number of orc bandits in the Misty Mountains further limited trade west. On top of that most of the possible trade partners west of Erebor had been destroyed in the millenia before the Coming of the Dragon. Moria and Hollin were empty with the dwarves of Moria gone to Erebor and the Elves of Hollin dead or gone to Valinor, never to return. The kingdoms of the Dunadain and of Gilgalad had been decimated earlier by the efforts of Sauron and the Witch-King of Angmar for political reasons. The Kingdom of Angmar had been destroyed by that war. The kingdom of the elves never recovered, being reduced to just Rivendell and the Havens. The remains of the kingdom of the Dunadain was under continual pressure from orcs and trolls due to Sauron’s desire to completely eradicate them. All of this significantly reduced the population, perhaps to as little as a tenth the number only a millinium before.

The political organizations in Tolkien’s Middle Earth aren’t well described as fuedal, at least if the comparison is to the High Medieval period. The Shire has a similar organization to the shire lands in England in the late 19th century, while the rest of the northlands is composed of communities where loyalty is person to person and doesn’t automatically pass from father to son.