For instance, on the planet Earth, man had always assumed that he

was more intelligent than dolphins because he had achieved so much—the wheel,

New York, wars and so on—whilst all the dolphins had ever done was muck about

in the water having a good time. But conversely, the dolphins had always

believed that they were far more intelligent than man—for precisely the same

reasons. - Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.

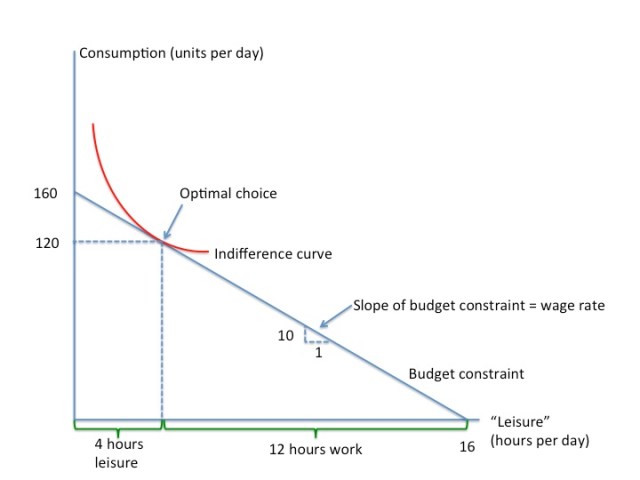

Time can be divided, approximately, into time spent eating,

sleeping, caring for others, playing, relaxing, making love – all the things

that make up "leisure" – and time spent in activities that generate

things to consume, or earnings to buy things to consume. An individual faces a

trade-off between leisure and consumption, as shown in the diagram below the

fold:

The diagram shows a person who is endowed with 16

waking hours per day. She can choose to spend them in leisure, or she can

choose to convert those hours into consumption by working. Her wage rate

determines how much additional consumption she gets for each hour that she

works. As drawn, our person's wage rate is 10 units of consumption per hour –

for each hour she works, she gets 10 units of consumption. For example, if she

has no leisure, and works 16 hours per day, she achieves 160 units of

consumption.

How much a person works depends upon her preferences, which I have

represented here by an indifference curve. Indifference curves map a person's wants, needs and desires. Each point on an indifference

curve is just as good as any other point, but higher indifference curves are

better than lower ones.

As drawn, our person's optimal choice – the one that gets her on

the highest possible indifference curve – is working 12 hours per day, achieving

120 units of consumption, and having four hours left over for leisure.

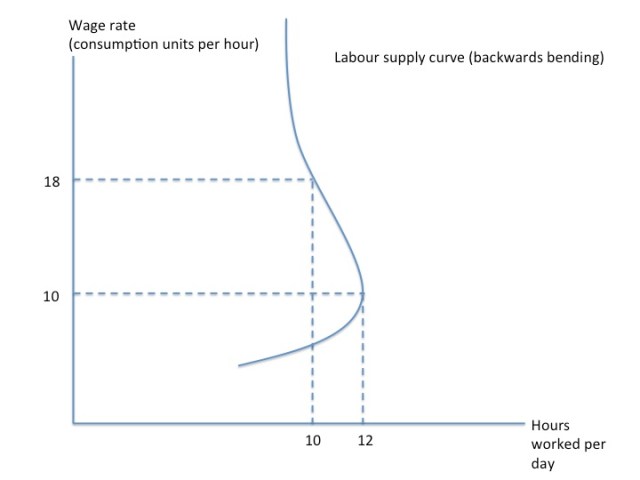

However if her wage rate changed, her budget constraint would

change too, and so would her optimal choice. In the second figure below, our

person's wage rate has increased to 18 units of consumption per hour, rotating

the budget line outwards.

In theory, the impact of an increase in the wage rate is ambiguous.

Work pays better, so taking time away from work, or enjoying leisure, costs

more. This means that people tend work more hours, substituting consumption for

leisure – the "substitution effect". At the same time, when work pays

well, one doesn't have to work so hard to get enough to eat, and instead can

afford to take time off – the "income effect". Whether an increase in

the wage rate increases or decreases hours of work depends upon which

dominates, the income effect or the substitution effect. In the diagram above, the income effect dominates. When a person's wage increases, she

works fewer hours – she has what is called a "backwards bending labour

supply curve."

The phrase "backwards ending supply curve" describes

what you get when you take the wage rate/hours worked combinations from the

diagrams above and plot them on a graph, like this:

In my

experience, students are often skeptical about the existence of backwards

bending labour supply curves, and regard them as just another one of those

weird things profs put on exams to trip people up. Yet a number of studies have

found that male labour supply curves bend backwards, especially those of

married men already in the labour market (see, for example, recent and

comprehensive surveys by Keane and

by Evers,

de Mooij and van Vuuren).

In fact, backwards bending supply curves are only natural. Pigeons

pecking for grains have labour supply curves that are upwards sloping at low wage

rates, but then bend backwards at higher wages,

as pigeons become less inclined to substitute pecking for other pigeon

pursuits. The labour supply curves of rats and mice are also backwards bending.

Indeed, one of the thing that is striking about observing animals in the wild, particularly predators like lions, is what slackers they are. Your average lion snoozes his or her day away. Those pictures of a lion staring down a wildebeast or an impala or a tsessebe? All the lion is doing is staring. She's won't try to run down an antelope in broad daylight – that's far too much like hard work.

After all, consuming

stuff is good, but there are other things worth doing in life, like mucking

around in the waterhole, having a mud bath, caring for family, fighting over

women, or making love.

Other than having an excuse to post pictures of elephants, what's the point?Understanding why people (or animals) work helps illuminate the impact of changing technology. Animals demonstrate backwards

bending labour supply curves in laboratory experiments because they’re paid in

food, and an animal only needs so much food. Humans are paid in money. They

will devote their efforts to paid work if it is a relatively good way of getting

the things people really care about – sex, status, and security. In the recent

past, it has been, but it may not be in the future. As I have argued before the world of virtual reality offers an alternative way of achieving a good

life, one that does not rely on paid work. If paid work becomes relatively less

appealing, and time for other things more, people’s labour supply choices will change.

Another motivation for this post is that backwards bending labour

supply curves matter for public policy debates. Take, for example, the question

of tax policy. The lay person’s understanding of tax cuts goes something like

this “tax cuts are good because higher wage rates mean people work harder.”

When labour supply curves are backwards bending, however, tax cuts may mean

people work less hard. As Keene argues, there may still be good efficiency arguments for reducing tax

rates, even if labour supply curves do bend backwards, but the simple higher

wages = more work effort argument does not stand up to serious scrutiny.

Or take, as another example, the question of pay for executives and other high earners. If

labour supply curves bend backwards, paying an executive more will not generate

any increase in work effort. In my view, high salaries are not about creating incentives for work effort. Firms pay their CEOs high salaries for the same reason that NHL teams write multi-million dollar contracts for star forwards and winning goalies – they want to attract and keep star players. The NHL realized that such bidding wars harm team owners, and so brought in a salary cap to stop them.

Perhaps shareholders need a Gary Bettman?

Can’t they just take the Gary Bettman? Please?

Top five dying regrets: http://www.alternet.org/5-top-regrets-people-have-end-their-lives. Number two is “I wish I hadn’t worked so hard.” What does that say about income effect versus substitution effect? About the conflict between the “remembering self” and the “experiencing self”?

And how much would dolphins work if they had opposable thumbs (aka a higher wage rate, I guess): http://www.theonion.com/articles/dolphins-evolve-opposable-thumbs,284/.

K – yes! 😉

Phil – that’s a fascinating observation about people’s dying wishes, though I don’t know if it says much about income and substitution effects. I suspect one could look at this from a behavioural economic perspective and figure out how people get sucked into working too hard – because work is so salient, or because people are overconfident about their chances of success or because, as you suggest, there is a difference between the remembering and experiencing self.

Robert Prasch: “Revising the labor supply curve: implications for work time and minimum wage legislation.”

David Spencer: ““The Labor-Less Labor Supply Model” in the Era Before Philip Wicksteed.”

Robin Hanson on death bed regrets.

http://www.overcomingbias.com/2010/11/deathbed-regret-is-far.html

Wonks – there I was, just about to quit my day job and devote my life to helping AIDS orphans in Zambia, and now you tell me those regrets about spending too much time at the office are just indirect boasts and/or a predictable effect of pain-relief meds!

I read in a USA study/report/article (which I don’t know how much validity to put on it) that stated that your typical worker was happiest and satisfied when their salary reached $74,000, any salary about this level they noted there was not an increase in happiness and in fact at really high salaries happiness started decreasing.

I’m the first to suspect these types of pop journalism stories, but since it fits my own experience disturbingly close I for one believe in backward bending labour supply curves.

As Francis said, an important factor is age and family situation, when I was younger I didn’t mind working a few extra hours and weekends, now that I have kids to take to/from school and daycare its really hard to voluntarily work extra hours. Not to mention the fact that most office/professional workers get a fixed salary and no overtime. The year end bonus to work harder isn’t a serious inducement when you factor in the actual average hourly rate you get.

I am trying to fit this into my ideas about why it is that people start having fewer children as they get richer. I figure that’s because the opportunity cost of caring for children rises as wages rise. But that only seems to work as an explanation if the labour supply curve slopes forward.

Is it just that, in the region where this transition occurs, it is forward sloping? Might it be that, if wages rise higher, people might start to have more children again? But then, ought not richer people today have more children than poor people?

Paul: rich people don’t have more children by number but they typically invest more in them. Total expenditures and human capital still rise. Like a modern army: no longer hordes of conscripts but highly trained Green Berets and pilots…

Might it be that, if wages rise higher, people might start to have more children again? But then, ought not richer people today have more children than poor people?

Maybe another way of looking at it as children as consumption/investment goods. To the extent one derives pleasure from having children (and, let’s be honest, while kids are an inconceivable pain in the ass, they’re fun to have around), they might be considered a consumption good and to the extent that they might care for you when you’re old and feeble, they might be a good investment. If you’re Richie Rich, kids are just one of many consumption goods and one of many investment choices. On the other hand, no matter how poor you are, you can always have kids (and, at least in the West, the government will kick something in to help you out to some degree).

Also, I think the problem with linking number of kids with wage rates is that there isn’t a clear link between wage rate and the cost of raising childen. Yes, if I quit my job and raise my kids, the cost of raising my children is directly linked to my wage. On the other hand, if I hire a nanny or put the kids in day care, then the cost of raising my children is some fraction of my wage, and is more or less unrelated to my wage rate (unless you have a geared to income child care subsidy). I’d suggest the latter is the more common arrangement.

There are some reasons that people work that don’t nicely fit into economic models.

People work because it give them status.

People work because the like it.

People work because they like the people.

People work because they think the work itself is valaubale — it makes people feel better about themselves.

People work because sitting around the house gets depressing.

As technology creates new products that you never knew you wanted, does the margnial utility of annother dollar increase. It was thought that as productivity increased people would work less. It doesn’t seem to be the case.

Actually, I think all those features can be (and are) readily reflected in standard economic models, i.e., they’d shape the labour supply curve in the 2d model that Frances presents above. They’re typically not presented in the sort of graphs that Frances provided ( i.e, 2 dimensional graphs showing the relationship between wage/hours holding everything else constant), but economists have no trouble modelling n-dimension labour decisions reflecting wage, hours, the cost of effort, status, utility from working, etc.. They’re just harder to put into a chart that the human mind can process for a blog posting.

isnt it clear that people generally work less when a country becomes richer, and that people in poor countries generally have longer working hours than in rich countries?

Doug M – the point of the post is (in part) this:

– animals have backwards bending labour supply curves, because there’s only so much food one wants, and time can be more enjoyably spent grooming, bonding, playing in the waterhole, etc.

– humans don’t always have backwards bending labour supply curves, and that’s because work gets us things like status and respect, i.e., the things you mention in the comments

– however with the changing nature of work (how much status and respect does one get working as a telemarketer? a barrista?) that connection between status, respect and work may be severed

– if so, we can expect labour supply curves to shift

Jacques Rene, unusually, I find myself disagreeing with you. The relationship between income and # of kids isn’t the same at the individual level as it is at the country level. Yes, on average, richer countries have fewer children (the US is an exception here). However at the individual level, the # of children is U-shaped in income, that is, the people who have the most children are those who are relatively poor and those who are rich – after all, if money is no object and one has a nanny and a team of other support staff, why not go for it?

Bob – The impact of wages on # of children depends on whether one is talking about male or female wage rates. IIRC fertility goes down in recessions suggesting that unemployment – lack of any wages – is a barrier to having children.

nemi – “people in poor countries generally have longer working hours than in rich countries?” Again I think there’s a non-linear relationship, and the experience of men and women is quite different. Work hours for men have steadily fallen as incomes have risen in N. America and Europe over the last century. However if one goes to a poor country like say, Zambia, there is very widespread unemployment, and a good number of people seem to spend most of their time hanging out in the shebeens (taverns that sell home brewed beer). There’s only so much one can work when there’s nothing to do.

– however with the changing nature of work (how much status and respect does one get working as a telemarketer? a barrista?) that connection between status, respect and work may be severed

– if so, we can expect labour supply curves to shift

I would not call it the “changing nature of work” but the changing availability of work. This post assumes that labour is short and it is workers that make the choice whether to work or not. I see more evidence that the contrary is the case, that people want to work but can’t than there is work to be done but not enough people to do it. Involuntary Unemployment gets short shrift in this model.

Claims of a “structural problem” really amount to the rampant phenomenon of “Purple Squirrels” in hiring rather any actual insurmountable shortcoming.

Good, up to the last bit. If high executive salaries are needed to attract star players, caps would need to be agreed to, not only by shareholders of all companies, but by anyone who could be a shareholder of an as-yet unborn company.

I think it would be more important for America to put its doctors back on the upward-sloping portion of their supply curves. Why subsidize medical care so extravagantly, and then let the AMA limit supply?

Frances,

That make sense, although anecdotally, at least in the legal profession, fertility went up during the last recession (i.e., there seemed to be a sharp increase in the number of woman lawyers having children. That might reflect the oppotunity cost story (i.e., when the legal market tanks, the cost of taking a year off to have a child falls) or a job preservation strategy (thinking that law firms are less likely to lay off a lawyer on maternity leave than a working lawyer who just isn’t that busy). In any event, it was quite stark in 2009.

Better term for it.

The opposite of work is not leisure. Leisure is a complement to work that one can make once one has work. The opposite of work is unemployment which due to a lack of money is not leisurely.

Determinant nailed that one.

Doug: about working for nonmonetary reasons – I remember reading one essay from Keynes and he suggested that fiven enough technological advances people may end up working about 15 hours a week. That he observed, was aproximately an ammount of work rich spouses of rich partners were willing to do to keep their self-respect. It was mostly work on charities and the like.

I understand that it was by no means a scientific observation, but it seems right to me. Maybe we humans are not that different from lions.

Determinant: “the changing availability of work”

In South Africa, there’s no such thing as a self-service gas station. One pulls one’s car in, and then a team of attendants leap to your service – washing windows, putting gas in, etc. They might earn 3, 4, 5 dollars a day – I don’t know – but it’s better than nothing. Entrepreneurial types get themselves official-looking vests and monitor car parks – they’ll stop the traffic and help you back out if you’re parked on a busy street, and then ask for a small tip.

There’s work available in Canada – anyone could do what so many in poor countries do, become a “trader” or sell home-made goods at an informal marketplace – the question is whether or not that work pays a living wage, uses people’s skills, and allows them to live with dignity.

That’s what I mean about the nature of work changing.

I have paid with the idea of a “leisure theory of value” in which traded “goods & services” are only intermediate goods. In order to enjoy the goods and services we buy, we also need leisure time. We can if we are paid enough, substitute capital for labour in creating utility, but their are diminishing returns. (P.S. Inside a household, you can also to some extent substitute one persons leisure for another so long as the utility being maximised is household utility).

I think it makes these issues clearer.

“However if one goes to a poor country like say, Zambia, there is very widespread unemployment”

That is about labour demand, not supply. And women, well, isn´t that more about “culture” (yes – I to hate when that word is used as an explanation – but you know what I mean). In many cases, women has entered the work force in large numbers during relative short time periods – generally not due to causes that seem to have to much to do with some shift in the wage structure.

I.e., as far as I can see – there is a clear pattern between wage and working hours – and it is a negative correlation (with a lot of noise – as always)

http://wws.princeton.edu/news/Income_Happiness/

Frances,

Matthew Yglesias had an interesting point about this: basically he says Greeks work more than Germans because they have to.

http://www.slate.com/articles/business/moneybox/2011/12/european_financial_crisis_is_europe_a_mess_because_germans_work_hard_and_greeks_are_lazy_.html

You’re curves are beautiful. How did you make them?

Frances: 1) I am so old I remember when North American gas stations had that swarm of attendants. ( The windshield-washing has since been subcontracted to the squeegee kids…). A good joke in “Back to the future ” was Marty McFly coming into a 1955 gas station and the swarm came in to his bafflement.

It’s possible that billionnaires would like to express their wealth and virility by having dozens of children. Few billionnaires’ wives seem to willingly volunteer for the task.

Sultan Moulay Ismail

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ismail_Ibn_Sharif

is reputed to have had 888 children but he had a really big harem…

BTW, he had 525 sons and 342 daughters, an excess of sons over daughters that is common among powerful men.

see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sperm_Wars

What happens if one ignores wages/money and goods values and looks ar calories? After all the animals you cite are measuring stuff in calories. In fact all human activities except idle daydreaming and inner experience can be expressed as energy dissipatioun.

Substitute wages per hour for calories per hour. Here you would need to be able to calculate an hourly energy consumption rate based on the energy cost of consumption of goods and services.

I suspect we’d see that those high earners energy consumption is not vastly in excess of the low earners, or at least the difference would be a lot less than the differences in nominal incomes. Maybe we’d find that all the curves would be backward sloping and in that sense we are little different to lions, and then we’d have to have a serious think about how a significant difference in the curves for energy per hour and income per hour can be explained an interpreted.

Frances:

The root problem is that you assume that work and leisure are independent goods and that therefore work vs. leisure will be a function, that for every unit of work there is a corresponding single value of leisure.

That is empirically false. If you define “leisure” as “not work” then there are multiple values of leisure for each unit of work, therefore work vs. leisure is not a function and the values are not independent. There is a third variable at play, in this case obviously income.

There’s work available in Canada – anyone could do what so many in poor countries do, become a “trader” or sell home-made goods at an informal marketplace – the question is whether or not that work pays a living wage, uses people’s skills, and allows them to live with dignity.

That’s what I mean about the nature of work changing.

Where’s the Marginal Theory of Value when you need it? If a unit of labour cannot earn an acceptable return, it has no value and is worthless. One cannot call workers irrational for refusing to supply labour deemed by the market to be of no value.

The problem in economics is that really, really basic assumptions and eliminations don’t fall out when people move to more advanced issues and then you get dreadful, nonsensical conclusions like the Great Recession was a spontaneous mass increase in leisure.

marris – I do all of the charts in powerpoint – it’s a fairly decent graphing tool, and it means that they’re the perfect size for incorporating into lecture notes.

nemi – that’s the subject of the next post.

Jacques Rene – I love Back to the Future, but it scares me that we’re now as far away the 80s as the 80s are from the 50s.

scepticus, yes, working for calories v. working for status/respect/other good things is the crucial distinction between people and other animals. The more I think about it, the more I like Phil Koop’s observation about dolphins earlier – it’s the opposable thumbs that allow us to work for things other than calories.

Well, everything can be reduced to calories, they don’t have to be burned in a human body (e.g. extra-metabolic).

By expenditure on “opposable thumbs” stuff I assume we refer to extra-metabolic energy consumption of industrialised humans. Because everything we do outside our very own mind can and should be accounted for in calories.

What I am saying is that if we take the work-calorie curve to include all the extra-metabolic energy expenditure of the individual under analysis, that the indifference curve will still be close to that of an animal, albeit of a different scale (for example, including extra-matabolic sources gives an industrial human in a developed economy the equivalent biologically scaled body mass of two adult sperm whales).

And then I am further supposing that the energy-work and income-work curves we get for this meta-human-whale thing, dont bear much resemblance to one another. Thus one would need to conclude that the differences relate to consumption of “stuff” that somehow has little or no actual physical manifestation of any kind (that could be measurable by science) in the real world. One might for example find huge differences in total energy consumption inequality and income inequality (in fact, there is a lot of evidence that energy inequaliy is much lower than income inequaity).

Alternatively we might find that the curves are very close, in which case it would be very reasonable to conclude that everything we do is ultimately directed at energy dissipation whether we call it leisure or work and the evolution of the economy as a whole really doesn’t care which.

A discovery either way would be of huge value in economics and might serve to build some useful bridges between micro and macro economics and ecological science. By way of example, I note determinant’s objection about ‘mass leisure’ yet looking at world energy consumption the GFC is a very small blip indeed.

It seems that a big wrench in all this beautiful research is the rigidity of labour markets. I would dearly love to work a high paying job for ten hours per week. But that’s not an option. It’s kinda hard to intuit peoples’ preferences based upon the choices they make when the number of choices is so tiny. Perhaps you could present your insights about labour rigidity in a future post…

From an inverview with Emmanuel Saez on rent seeking: “For example, Clinton in 1993 limited the deductibility of top executive pay for corporate tax purposes to $1 million per person unless the pay was tied to performance.”

Maybe that’s a good way to do it. But don’t permit any “performance” exceptions. Of course, with corporate tax rates collapsing globally, it might not make much difference. Probably the solution is just very high top marginal tax rates. If the shareholders refuse to collect the rents, it’s better if the public does it anyways.

@scepticus: “Well, everything can be reduced to calories, they don’t have to be burned in a human body (e.g. extra-metabolic).”

And everything can be “reduced to” class structures, or sex drive, or reproductive fitness, or…

But what all of that really means is that, from reality, which cannot be “reduced” at all without falsehood, we can abstract a view that puts everything in terms of calories, or class structures, or sex drive, etc.

Gene, not really. There is no objective method of accounting besides energy. This may sound silly, but it really isn’t unless one adopts a strictly anthropocentric view in which individual and collective human activity is not subject to any of the natural scaling laws that apply to other lifeforms on this planet and indeed to such phenomena as body size.

At which point one is free to speculate that anything is possible and generate whatever abstractions one feels may make the desired point.

Hence my assertion that results of any general applicability about (for example) income/labour indifference curves cannot be derived when (for example) an objective definition of leisure is an impossibility.

Such work can never amount to anything more than a talking shop.