The

The

completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) in 1885 was more than an

impressive engineering achievement; it was also a significant

joint economic undertaking by the public and the private sectors and a key

ingredient in Canadian nation building as it provided the east-west transport

corridor that made the Canadian west an investment frontier. The building of the CPR demonstrates

several important points with respect to the conduct of public policy in Canada

in the 19th century that remain relevant to the present day. Moreover, the economic significance of

railroads in Canada persists today as their cargo statistics provide a

convenient indicator of economic activity.

Point 1: Choosing a route for anything in Canada,

whether it is a railroad, highway or pipeline, is always a contentious issue.

Politics usually trumps economics. The

final route of the CPR was controversial with the key dilemma being whether to

have a more expensive all Canadian route or a cheaper route that partly went

through the United States.

In Central Canada, the rugged and rocky

Canadian shield was an expensive geographic obstacle. Given the expense of

building through the Canadian Shield, a number of proposals for the line from

Ontario to the West had been made. Most of these proposals involved going

through the United States and coming up through Minneapolis and Red River to Winnipeg.

Another rather interesting proposal suggested a main trunk line from Winnipeg to

Fort William, a ferry link to convey the rail cars across Lake Superior, and a

connecting line at Sault Ste. Marie.

The limitations of such a route during a Canadian winter are obvious.

In the West the debate was over a cheaper more

southerly route that would take the railway through the arid Palliser's

Triangle and a more expensive northerly course through Saskatchewan, Edmonton,

the Yellowhead Pass, and then down to Kamloops and Port Moody. The discovery of the more southerly

Roger's Pass eventually cemented the choice of the southern route despite

concerns about the aridness of land in the southerly route while the more

northerly route became the route of the Canadian National Railways.

Ultimately,

the Canadian government chose an all-Canadian route, in spite of the expense of

laying track around Lake Superior with the grounds for this decision being the

political requirements of nation building. Given that the Western railway

project was a nation-building exercise and a defensive action to secure the

North-West Territory for Canada against American expansion, it made little

sense to have the route go through the United States. As well, the all-Canadian

CPR project was in Britain's imperial political and military interests; as Vernon Fowke wrote

in The National Policy and the Wheat

Economy: "It was also to be a link in an imperial chain, a vital part

of the 'all red route' which was to bind together the various portions of the

far-flung empire."

Point 2: Public private partnerships seem

always seem to end up costing a lot more than was anticipated. Building infrastructure

is a risky business. The CPR was a Canadian

"mega-project" constructed by the government in conjunction with

private interests. The slow

performance of the Mackenzie government in railway construction during the

1870s was taken as evidence that the project was so capital intensive that public

assistance was needed in the form of land and cash subsidies as well as various

tax exemptions. As well, there was

not a host of private investors lined up to build transcontinental railways in

Canada without public assistance.

Indeed, public assistance for railway building was common in most countries

in the nineteenth century.

The

general consensus amongst economic historians is that, in the absence of

government assistance, the CPR would not have been built when it was but rather

would have been postponed to a much later date when the much denser Western

population needed to support rail traffic and generate an adeuate market return was present. At the same time, postponing

construction risked the construction of north-south lines linking Canada into

the American rail grid and eliminating any need for any Canadian

transcontinental rail line at all.

Thus a subsidy was needed but ultimately too much was paid.

The amount of Dominion government assistance

provided to the CPR was quite substantial since the Macdonald government, after

its re-election in 1878, had found no private bidders for the project. The Syndicate put together in 1880 to build the railway received the

following in return for completing a railway from Northern Ontario to the

Pacific by May of 1891.The terms seem to have been sufficient incentive to complete the project six years early.

·

First

the Dominion government was to provide a direct subsidy of $25 million

in cash and 25 million acres of land.

·

Second, sections of track already built by the

government at its own expense were to be given to the CPR without charge. This

provision referred to the sections of track built from Fort William to Selkirk

and from Kamloops to Port Moody—700 miles of track costing approximately $38

million.

·

Third, all materials required for the

construction and operation of the CPR were to be exempted from taxation. As

well, all imported construction materials were to be allowed into Canada

duty-free. Moreover, CPR lands were not to be taxed for twenty years unless

they were sold or occupied.

·

Fourth, the government promised not to regulate

freight rates until the CPR was earning a 10 per cent return on its capital.

·

Fifth, the construction of any competing railway

south of the CPR was prohibited for twenty years. This stipulation was known as

the monopoly clause of the agreement.

According to Peter George’s classic study, the

subsidies paid to the CPR in 1885 constant dollars exceeded the

needed subsidy (based on estimates of the private rate of return for comparable projects) by amounts ranging from $61 million to $39.8 million to $34.1

million. George thus concluded that the value of the subsidies

awarded to the CPR by the government of Canada were indeed excessive. He

cautioned, however, that the value of the subsidies can be seen as excessive ex post and that a complete answer would

also involve examining the value of the subsidy during the ex ante circumstances that governed the setting of the contract

between the CPR and the Dominion government.

J.C. Herbert Emery and Kenneth McKenzie more

recently argued that the ex post

perspective, which values the size of the excess subsidy after the fact,

ignores the high degree of risk associated with these projects at the time the decisions

were being made. The ex post

perspective, by not taking prior uncertainty into account, will almost always

condemn government subsidization as inefficient. The transcontinental railway

line should be viewed as an example of a "once-and-for-all"

irreversible investment made under uncertainty. They conclude it is quite likely that the portion of the

subsidy granted to the CPR that traditionally has been viewed as excessive may

well have been required to compensate the company for foregoing its investment

option. Thus subsidies that seem

excessive in hindsight may have been justified based on the investor

expectations of the time.

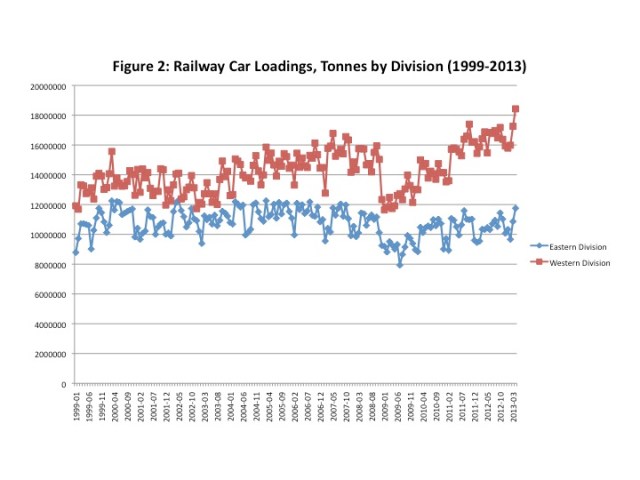

Point 3: Railways were important in the

nineteenth century. They are still important now. The CPR and the subsequent transcontinental lines carried the life blood of the Canadian economy during the wheat boom era and beyond. For decades, they were the only way to effectively traverse the country with people and goods. It is amazing how closely railway cargo statistics still

track the ebb and flow of the Canadian economy. The accompanying figure shows statistics for monthly railway

car loadings for Canada from 1970 to 2013 and combines it with a LOWESS Smooth

(with a 0.1 bandwidth). It is

fascinating how despite the 20th century onset of roads and highways

for bulk road transport as well as air transport of freight, railway freight

since 1970 exhibits upward movement and its fluctuations mark recessionary

periods quite distinctly. For

example, there are pronounced slowdowns and/or downturns in tonnes of traffic

for the 1973-1974 period, 1981-1982, 1990-1993, 2000-2001 and 2006-2009. Indeed, in several cases (the 1991-92

recession and the 2009 recession), one can argue that the rail cargo statistics

may have been an important leading indicator forecasting the subsequent

recession. As well, these railway

statistics also show the recent divide in economic activity between eastern and

western Canada. (Note that cargo loadings from Thunder Bay, Ontario, to the

Pacific Coast are classified to the Western Division while loadings from

Armstrong, Ontario, to the Atlantic Coast are classified to the Eastern

Division). As Figure 2 shows, since 1999,

freight traffic has been going up in Western Canada while it has remained

essentially static in the east.

This figure also shows a rebound in activity in the west after 2009 but

not in the east.

Railways

are indeed a fitting topic for the 2013 edition of Canada Day. Issues like choosing a route, whether

or not to provide a public subsidy and how much of a subsidy to provide have a

lot of parallels to the infrastructure networks of the present day whether they

are pipelines, highways, public transit or electricity grids. Have a great holiday.

Bibliography

Berton, Pierre (1971) The Last Spike. McClelland and Stewart.

Emery, J.C.H. and K.J. McKenzie.

"Damned if you do, damned if you don't: an option value approach to

evaluating the subsidy of the CPR mainline." Canadian Journal of Economics 29:2 (1996): 255-270.

Fowke, V.C. The National Policy and the Wheat Economy. Toronto: University of

Toronto Press, 1971.

George, P.J. A Benefit-Cost Analysis of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Ph.D.

Thesis, University of Toronto, 1967.

George, P.J. "Rates of Return

in Railway Investment and Implications for Government Subsidization of the

Canadian Pacific Railway: Some Preliminary Results." Canadian Journal of Economics 1:4 (1968): 740-762.

George, P.J. "Rates of Return

and Government Subsidization of the Canadian Pacific Railway: some further

comments." Canadian Journal of

Economics 8: (1975): 591-600.

Statistics Canada: Railway Car Loadings

D5324, v74869, v783501; v783644; Canada; Total traffic carried; Tonnes.

Related articles

// <![CDATA[

var sc_project=9080807;

var sc_invisible=1;

var sc_security="4a5335bf";

var scJsHost = (("https:" == document.location.protocol) ?

"https://secure." : "http://www.");

document.write("<sc"+"ript type='text/javascript' src='" +

scJsHost+

"statcounter.com/counter/counter.js'></"+"script>");

// ]]>

Livio, interesting post. It would be interesting to take that second graph back in time a bit, because it shows quite dramatically the rise of the west relative to the east.

One comment: “Politics usually trumps economics.” One thing that I always found fascinating about the history of the railways is the extent to which the developers bypassed existing towns, bought up all the land in some less built up place, and then located crucial junctions there. So politics might trump wider economic interests, but not the personal gains of the developers!

Not everyone would be familiar with Pierre Burton’s The Last Spike – not economics, but perhaps something to add to the references as a good general introduction? Or would you figure it’s not accurate enough to be considered a good general introduction?

No, Pierre Berton’s Last Spike is a great introduction to the building of the railroad. Thanks.

A railway thread!!! Oh Goody goody gumdrops! 🙂

So politics might trump wider economic interests, but not the personal gains of the developers!

Railways in the 19th century with Land Grants (west of Chicago, in the US) more often has as a “pump and dump” scheme rather than a long-lived infrastructure project. The goal was to build the line, develop the land, catch the boom and sell off the land; then the investors would be gone and move on to the next scheme.

The CPR expressly said it wouldn’t follow that model and would instead earn its revenues from operating profits. It would also try to keep all profits for itself, which is why it turned into a conglomerate with ships, hotels, telegraphs, mines, etc. The “operating profit” model also worked well with the government’s desire to use the CPR as its development agent.

As a reflection of this, 70% of all US railway companies have been bankrupt at one time or another, oftentimes more than once. Prior to 1930, railways were the bulk of the US stock and commercial debt markets. Ben Graham, author of “Securities Analysis” and “The Intelligent Investor” cut his teeth on railway securities; he devotes extensive sections in both to the analysis of railway debt and commercial paper and his passion and love of these specific markets shows.

The rise in the freight share of railways since 1970 is due to the rise of intermodal transport (containers and flatcars with trailers) and railway deregulation. I worked for a company that did regular shipments to BC, we were advised that railway intermodal with a truck for the “first and last mile” was the cheapest option.

Glad you liked a railway post Determinant! Point about US railways being the bulk of stock and commercial debt markets interesting. The modern corporate form developed in the early 19th century because of the financial needs of railroads. Railway debt was quite large in Canada too.

The shift in rail freight from Eastern Canada to Western Canada is largely due to shift in demand of agricultural and natural resources from Europe to Asia. It was in the mid 1970s roughly that the port of Vancouver started to overtake the Great Lakes as the main output for Canadian wheat. There was actually a short period of time when Canada was still exporting the majority of its wheat shipments to China through Thunder Bay and the Great Lakes. I have an old article somewhere discussing the buildup in port infrastructure in Vancouver and Prince Rupert during the Trudeau and Lougheed era’s. Basically it was a Lougheed initiative after the PC’s threw out the old Alberta Socreds. Thunder Bay has always been the main port for wheat exports to the East except in winter when they were railed to whole way to Halifax, Quebec City etc.

Note. The CN rail line to Thunder Bay(not the CP line) runs through Minnesota for a short distance. The main CN line to Eastern Ontario and Quebec though runs well to the north of T’Bay and is on Canadians territory for the whole distance as is the CP line.