At a family party in the Toronto exurbs, right on the outer edge of the 905 zone, one of my favourite cousins cornered me. "You're an economist," he said, "tell me why you think carbon taxes are a good idea."

My first thought was to sidestep the issue. "They're only a good idea," I said, "if you think global warming is a problem. If you don't think people consume too much by way of fossil fuels, then there's no need for a carbon tax."

Then I tried the economic freedom line: "A carbon tax makes fossil fuels more expensive, so people have an incentive to consume less. The great thing about them, though, is that people have a choice about how to cut their consumption."

"Think about the alternative," I said, "Do you really want a bunch of new regulations, people saying what you can and cannot do? This way there's no need for a big government bureaucracy, and people decide what's best for them."

Neither of these arguments made the slightest impression on my cousin. "I don't believe this talk about revenue neutrality," he said, "there won't be cuts to other taxes. The government will just take the money and spend it on useless things like your salary." [Note: he denies saying this.]

This was a low blow, especially coming from someone who also lives off taxpayer dollars (though I suspect, knowing my cousin, that getting this jab in might have been the whole point of the conversation). There was another, more persuasive, point he could have made: just look around you.

In the exurbs, it's possible for a single-earner family with a decent middle-class job to buy a home big enough to host a family party, with a two car garage, a garden, and a luxuriously large kitchen.

A carbon tax works because it makes commuting from the exurbs prohibitively expensive. Leaving the exurbs means not having a garage big enough to work on restoring a 1966 Mustang. It means giving up the backyard pond and the garden and the barbecue. It means taking a capital loss on a home that is no longer desirable, given the cost of getting to work.

If economists want to sell carbon taxes, we have to face up to their distributional consequences. In Toronto, there are (roughly speaking) two groups who would gain from a carbon tax.

The first group is those who cannot afford to use carbon. According to this study, the Torontonians with the smallest carbon footprint are those who live in the high rises and housing projects of East York. They have small living spaces, hence low heating costs, and take public transit. A BC-style carbon tax, which includes a refundable tax credit for low income individuals, would make these people better off.

The second group that gains from a carbon tax are those prefer a lower carbon lifestyle, and can afford to indulge their preferences. They're the people who think of their car (if they own one) as a recalcitrant, overpaid, employee, but pamper their bicycle with special botanical chain oil from Mountain Equipment Co-op. They live in Toronto's waterfront condos, or in areas like little Italy. A reduction in income or consumption taxes, financed by an increase in carbon taxes, would be a clear gain for the higher income, lower carbon demographic.

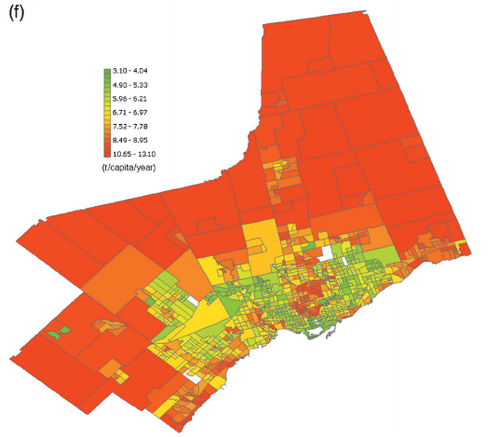

The biggest losers from a carbon tax are people like my cousins in the exurbs. The map above, taken from a paper by VandeWeghe and Kennedy, highlights the parts of Toronto with the highest per capita carbon consumption in red. These are place where people live in reasonably large houses, and commute long distances to work, generating whopping carbon footprints.

The whole purpose of a carbon tax is to discourage this type of lifestyle. But I can see why people are reluctant to give it up. Except for the commute, it's great. The streets are quiet, clean and friendly, and there's lots of green space near by. For a person who wants a garden and ample living space, the alternative housing options in the same price range are clearly less desirable: a small, unrenovated bungalow in Scarborough, say, or a downtown condo.

The most valuable lesson economics teaches is that people aren't stupid. Greg Mankiw might say that the basic case for a carbon tax is “is so straightforward as to be obvious.” Here's something else that's obvious: carbon tax hurt in the exurbs.

Great post. Is there any information/evidence from BC on backlash from the Exurbs to the tax? or whether it did indeed push down property values? or whether it made much difference to consumption?

My sense (I live in East Vancouver, so in BC but not in the exurbs) is that (a) the carbon tax is so small compared to the rising cost of gasoline and energy itself, that it hasn’t had a measurable impact. (b) the Vancouver exurbs are places like Chilliwack that don’t have a 6c/litre transit tax at the pump, which makes fuel there cheaper than in the metro area, and this discount kind of offsets the carbon tax. (c) suburban and exurban housing prices have been flat since 2008 in metro Vancouver, whereas (like in Toronto) prices have risen in the inner core, but I’m not sure I’d attribute that to the carbon tax as much as people deciding to value their time over the size of their home (and value the walkable, transit-oriented lifestyle). And the fact that a similar phenomenon has hit Toronto housing suggests that carbon taxes are not to blame for flat suburban home prices.

While I support carbon taxes and wish they were higher, I’m also not convinced that it’s having much effect on decisions. The carbon tax is buried with so many other levies and taxes that it has become invisible.

I think the new toll roads/bridges are more visible to people, and more likely to make a young couple or family think twice about selecting that suburban or exurban detached home over a townhouse in the city.

Has anyone studied whether toll roads have an impact on housing prices or purchasing decisions? or in the ultimate decision to consume less carbon by making other choices?

Frances, doesn’t the scale matter? Any reasonable carbon tax would not have a moderate or small impact on urban development. A carbon tax of $100 per tonne would be pretty substantial, and be equivalent to 25 cents per litre of gasoline. I don’t think that would be the death of suburbs, though it would incentivize more efficient vehicles, and investments in energy efficient homes (better windows, insulation, lighting and heating systems).

That suggests that a political party seeking to introduce a carbon tax should give some though to what its going to do with the money. For example, you might think about dedicating the revenue to, for example, fund suburban or exurban transit lines (think Go trains to Barie). I think you see that in road pricing schemes in California where the revenue from road tolls are used to fund bus routes on the same roads. It’s a polically saavy way to impose what might otherwise be unpopular taxation, because it allows politicians to present that taxation as, essentially, voluntary, by giving people a choice.

Plus, in the case of a road toll (and likely with a carbon tax too), you can present it as a win-win scenario. If you still want to drive, fine, it’ll cost you more, but there’ll be less traffic. If you don’t want to pay the carbon tax, we’re giving you a less costly alternative. Personally, I’d be more likely to drive with a carbon tax or road tolls if they would clean a lot of the traffic off the road.

I think the tricky part, reflected in your cousin’s comments, is the credibility of the government’s commitment to link carbon tax (or road toll) revenue to that particular spending program. Still, with something like transit expansion, because the capital cost is an upfront cost, there’s an implict commitment, since once the trains are bought or the lines are build, they need to be paid for.

My understanding is that carbon emissions have to drop drastically in absolute terms to stabilize climate change at less than a 2C rise, and many climatologists are now worried that at least 2C is already baked-in. Either way, a carbon tax would have to be very high to change behaviour enough to make a difference.

“It means taking a capital loss on a home that is no longer desirable, given the cost of getting to work. ”

Good point. Assuming a tax high enough to change behaviour, what would happen as people abandon the exurbs? Detroit replayed in every major urban areas? Would they walk away from mortgages? Would prices in ‘green’ areas rise dramatically, leaving people stuck with nowhere to live?

And after the catastrophe in Calgary, I wonder how many green areas will be subject to similar events, as they tend to be older neighbourhoods built on flood plains or near the (rising and stormier) ocean.

But isn’t the real problem the whole urban design of the Toronto metropolitan area. My model for the future will look like the Randstad or the Rhein-Main Gebiet (where I live), i.e. multiple compact centers with a (mostly external to the centers) network of major connections between them. Even with a compact center – people are always near green areas, and can have larger blocks on the edge of these centers. The concentric design is the real problem, it is not scalable.

The answer to the “government will just waste the money” argument is to distribute the cash equally as a citizen’s dividend. This makes the tax far more politically palatable because most people win (consume less than average), and the win will feel very tangible. Secondly, a citizen’s dividend will produce pressure to eliminate wasteful government spending on means tested transfer programs, ie it will create downward pressure on the size of government.

K,

An interesting idea, but ring-fences that join a tax with a form of expenditure seem to blow over very easily…

“Carbon tax hurt in the exurbs.”

While the following formulation isn’t nearly as pithy, shouldn’t it be more like: Carbon taxes would most likely increase the cost of taxes paid in exurbs while reducing the cost of externalities like air pollution, climate change, and commuting time. The net effect of this change for the exurbs is not clear, but the reduced costs are hard to see and will not be realized immediately, making it appear that carbon taxes hurt the exurbs, whether they do or not.

W. Peden,

Yes, but lots of expenditures don’t have a strong constituency. If you label it as a a God-given right, just and fair compensation for your share of suffering from future environmental wreckage, I suspect it’ll become as entrenched as social security. If anything, I think it would lead to a landslide of demand for taxation of other externalities (eg land/resource) that could be used to raise the dividend. I agree that the strength of the ring fence is critical, but the key is to secure it with a social construct based on rights (not redistribution!).

K,

Are social security contributions only spent on social security benefits?

ok, so the tax then gets baked in to the price of the property, rewarding and punishing the people who own these properties (not equal to the ones who live in them). equivalently, in order to make any change to the total footprint it has to change the pattern of how people live, in aggregate – and for that to be the case we have to be willing to let people build in density.

Part of the social construct might be to relabel the tax as a “compensation” levy. You, Mr polluter, need to pay compensation to the victims of your actions. The payments are routed straight to the victims, via a monthly payment to all citizens (not connected to the income tax system). Calling it compensation also has the useful effect of stigmatizing pollution (it’s the flip side of labeling the payments as a “dividend” or a “right.”)

K,

That sounds quite libertarian and retributivist. I like it.

Wendy – “people deciding to value their time over the size of their home”

I think that this is happening, and is partly due to changing technology – computers have replaced so much stuff that people don’t need as much space.

Your questions about housing prices and toll roads are very good ones. I suspect that the people who worked out the dollars and cents behind the Port Mann bridge project didn’t realize how financially precarious the lives of people who live in the outer suburbs are. This article suggests people have been choosing a new express bus over the bridge, but I couldn’t find any serious studies.

Andrew F: from the outer exurbs to the centre of the universe is, say, 70 km. Would you figure that’s 4? 5? litres of fuel for a one-way trip? So a 25 cents per litre carbon tax would increase commuting costs by $1 or $1.25 each way – say $1.50 if we’re talking on the high side. $15 per week or 15*50=$750 per year. That’s peanuts compared to housing prices, which suggests you’re right saying that carbon taxes wouldn’t mean the death of the suburbs.

But if carbon taxes don’t cause fundamental shifts in the way people live, are they likely to have a substantial impact on emissions?

Bob Smith: I was thinking along those lines too. The estimates of carbon tax revenue above ($750 per commuter) might fund a bus service or a park ‘n’ ride, but rail infrastructure requires big bucks. Is there an existing north-south right of way for rail that could be used? If not, the costs of acquiring the property would be prohibitive.

Patrick – one would expect carbon taxes to be capitalized in the price of existing homes. So essentially the cost of a house in the exurbs would fall by the present discounted value of the carbon tax payments, and the cost of homes in the inner city would rise. I would expect this to at least partial offset the impact of a carbon tax on people’s decisions about where to live. Where it would have more impact is going forward, as developing land in the exurbs would be a less financially rewarding proposition.

reason – to some extent that’s happening, isn’t it – places like Oshawa and Hamilton are centres in their own right. What’s missing, as Bob Smith pointed out, is the rail links between these centres. The other big difference with Europe is the very low density – small towns and villages in England are far more densely populated than small towns in North America. I suspect, thinking about it, that this probably has more to do with land use and agricultural policy than with the cost of commuting. Farmers in England might love to make millions by chopping up their family farm into little lots and selling it off for development, but they aren’t allowed to.

K – the distribute the cash equally/citizen’s dividend model is what BC did. That’s the model that benefits hippies and hobos, and really squeezes the suburban commuters in the middle.

“Retributivist”. I like it!

K “Part of the social construct might be to relabel the tax as a “compensation” levy”

You may remember my post Good-bye carbon taxes, hello atmospheric user fees?

Babar,

“we have to be willing to let people build in density.”

We need to get rid of stupid zoning laws and switch from property tax to land value tax.

W Peden,

Social security contributions go straight to a trust fund. All contributions and payments are external to the government budget.

Frances,

“That’s the model that benefits hippies and hobos, and really squeezes the suburban commuters in the middle.”

So what? The destruction of the planet “squeezes” the hippies and hobos, and apparently benefits the suburban commuters, on the balance, in their judgment.

But cars aren’t the major generator of carbon dioxide. That’s coal (and probably tar sands in Canada). So the main impact is on electricity prices – which spreads the costs fairly evenly. Here in Australia we have had a carbon tax for a couple of years. The money it raises was returned to taxpayers through a higher tax threshold and lower rates at the bottom, so most people were compensated for electricity price rises. It’s not popular, but what tax is?

It’s certainly not high enough, but the barrier to raising it is less the impact on the outer suburbs than the impact on coal mining regions. I suspect that Alberta is a bigger factor than the exurbs in the politics in Canada.

By the way, given that essentially coal is the problem, that a direct government effort to replace coal with renewables over a short time frame might well be the most effective and efficient solution. Anything else is messy and liable to gaming.

“I was thinking along those lines too. The estimates of carbon tax revenue above ($750 per commuter) might fund a bus service or a park ‘n’ ride, but rail infrastructure requires big bucks. Is there an existing north-south right of way for rail that could be used? If not, the costs of acquiring the property would be prohibitive.”

In the case of Barrie, there is an existing Go Line, but the trains are not regular or reliable enough to draw many people out of their cars. Most of the Toronto area suburbs are served by existing Go Lines, and there are plans proposed(subject to financing) for new Go Lines using existing rail lines. So, at least in Toronto, it would probably be feasible to expand transit service to exburbs at a reasonable cost given a revenue source, e.g. a carbon tax.

I’d be curious if there was any reasearch on the magnitude of a carbon tax (or road pricing) required to induce people to shift from driving to transit. My suspicion is people are actually quite responsive to pricing in choosing their mode of commuting. Back when Hurricane Katrina hit, the price of gas jumped, almost overnight, by a significant amount (I can’t remember the exact number, but I think it was something like 20 cents a liter). Not coincidentally, the Go Trains started becoming much more crowded.

K: “Part of the social construct might be to relabel the tax as a “compensation” levy. You, Mr polluter, need to pay compensation to the victims of your actions. The payments are routed straight to the victims, via a monthly payment to all citizens (not connected to the income tax system).”

The difficulty with that approach is that it’s politically unfeasible if the “victims” (or perceived victims) are less numerous or politically influential than the polluters, since such an approach compensates both “winners” and “losers” from the change in policy in equal measure. The policy may be socially optimal, but it won’t be implemented if the “losers” can block it. In Frances example, do the exurbanites have a louder voice in Parliament than the denizens of Toronto’s Little Italy? Probably.

In that context, there may be merit to compensating the polluters for reducing their pollution output (i.e., a polluttee pay” approach). I realize that’s an anathema to the environmental movement, but that’s an ideological objection, not a practical one. The difference between that “polluter pay” model, and the altenative “pollutee pay” model is a distributional one – both achieve the socially optimal result. If the distributional effects of a “polluter pay” model are a political impediment to achieving the socially optimal goal, there’s merit to considering the alternative “pollutee pay” model, and having the “winners” compensate the losers.

“I suspect that Alberta is a bigger factor than the exurbs in the politics in Canada.”

Maybe, and certainly what Alberta does has a big impact in the rest of the coutnry. On the other hand, the Exburbs around Toronto tend to be highly valuable swing ridings that make or break governments. The same ridings around Toronto that elected the current federal Conservatives also made the current provincial Liberals (and, 15 years ago, elected the federal Liberals and provincial Conservatives). In that light, the influence of those ridings shouldn’t be under-estimated

Why would rising gasoline prices deter people from exurban living? The cost of housing has risen dramatically (admittedly across all urban environments), but that doesn’t seem to have encouraged more families from accepting more downtown living. I think you hit the nail on the head though–making exurban living costlier means a direct hit to people’s biggest bit of capital, and why on earth would they tolerate that? You might as well tax exurban retirement savings to compensate for global warming. And of course, if there is sudden depopulation of the exurbs, the taxpayer is still left with managing the legacy infrastructure in those areas.

A huge challenge in Canada is that, for very obvious reasons, we have no cultural norm of dense urban living (other than downtown Toronto and Vancouver, and maybe Montreal). The benefits of suburban living are highly visible and usually within reach. As you say, it makes sense that so many people desire them. As much as I support the idea of carbon reduction and denser living, I think we underestimate the change that is needed for Canadians to embrace higher density as a norm. The incredibly dense living quarters enjoyed by so many people in Asia are offset by many things: a warm climate, a rich and highly competitive urban economy that makes dining out as cheap as eating at home, good-to-excellent transport infrastructure, and most importantly, social norms built around high interpersonal propinquity and very small personal space. A family of four in Tokyo or HK might easily inhabit a 600-sf apartment. I’m not suggesting we have to go that far, but the scale of improvements and shifting of norms is immense to get the kind of carbon reduction that’s needed in Canada.

Peter T: “It’s not popular, but what tax is?”

Answer: Taxes on people we don’t like (whoever we is): the rich, immigrants, exurbanites, MEC shoppers, etc….

Shangwen: “I think we underestimate the change that is needed for Canadians to embrace higher density as a norm…dining out”

The Asian/European difference in attitudes towards having people in your own home/dining out is really big and deep seated. I know it’s there, but I can’t really grasp it. When I invite my culturally Chinese friends over for a casual family meal or a big party, I don’t understand why they feel it’s such a big deal. When they reciprocate by saying “let me take you out to this great restaurant” it just doesn’t feel right: a restaurant invitation, to my mind, does not equate to being invited into someone’s home. But, yes, in the Chinese culture, one doesn’t have to have a big house in the suburbs to host family parties, because the proper way to host a family party is in a restaurant.

I think the key thing here is this:

“My first thought was to sidestep the issue. “They’re only a good idea,” I said, “if you think global warming is a problem. If you don’t think people consume too much by way of fossil fuels, then there’s no need for a carbon tax.””

I am amazed at how many people don’t really think it is an issue, and the even larger number of people who think it is an issue, but seem unwilling to do anything about it. In fact, it depresses me so much I have even considered joining the Green Party 😉

I am one of those people that live downtown (not Little Italy, but somewhere close by) and commute by bike/walking. I would possibly gain from an increase in property values from a carbon tax (although I would not really be able to capitalize that gain). However, I would also observe that many of the people who live downtown and who are part of the more cosmopolitan lifestyle also contribute to the problem in other ways, and would be harmed by an increase in carbon costs through the higher cost of air travel. Most people I know think nothing of flying to Europe or Asia, which creates huge quantities of carbon. This is the flipside of the benefit of a large house in the exurbs with a large commute – there are other forms at which we can all produce as much carbon as possible! It is not clear that the distributional effects are only driven by housing location (although clearly that plays a large role).

I know that none of this goes to the practical concern of how to convince a large enough coalition of voters to vote for a government who will put in a form of carbon tax. I just think that it won’t happen until enough people are convinced that it is a big enough problem that we have to do something about it. I am not encouraged that there is such a coalition.

“Why would rising gasoline prices deter people from exurban living?”

Depends on how much they rise, I suppose. Europeans pay substantially more for petrol, and they still drive a lot. A carbon tax would, in many places, increase heating and/or electricity costs too. That would help drive people out of their McMansions. I bet some enterprising econometrician has figured out how much it would have to be to make the absolute reduction of emissions required to stabilize the climate. Unfortunately, google failed me. My guess is that it’s way more than $100 per ton.

Bob Smith:

“In that context, there may be merit to compensating the polluters for reducing their pollution output (i.e., a polluttee pay” approach). I realize that’s an anathema to the environmental movement, but that’s an ideological objection, not a practical one. The difference between that “polluter pay” model, and the altenative “pollutee pay” model is a distributional one – both achieve the socially optimal result. If the distributional effects of a “polluter pay” model are a political impediment to achieving the socially optimal goal, there’s merit to considering the alternative “pollutee pay” model, and having the “winners” compensate the losers.”

I am not sure that this is doable. What incentives do you offer? Subsidize energy efficiency? This might just lead to more consumption as people have to pay less to do something with an equivalent amount of energy – compensate by helping to pay for twice as much efficiency in cooling your house? Great – now I can afford to build a bigger house! Or, for cars, now that engines are more efficient, we are building bigger and more powerful truck like vehicles, consuming the same amount of fuel, but for more car/power consumption per drop.

Unless you are going to put a strict regulatory regime in place to limit this issue, I am not convinced that there is a workable mechanism here. It seems this would require a command/control type regime which is problematic.

“But if carbon taxes don’t cause fundamental shifts in the way people live, are they likely to have a substantial impact on emissions?”

What if changing the behaviour of commuters is not the low-hanging fruit? This is sort of the point of using a carbon tax. If commuting from the suburbs is a high value-added activity, maybe we should not be concerned about making big changes in behaviour in this area. I can tell you that a $100 per tonne carbon tax would have major impacts in other areas, such as commercial transportation and manufacturing. It would create incentives to invest in more energy efficient equipment, such as trucks that run on natural gas or are more aerodynamic. Business practices might change to increase productivity (loading more goods on a truck, for instance). Consumers have an easier time justifying investments in hybrid cars. Industrial users might find it easier to justify cogeneration (power + process heat) and other technologies.

A $100 per tonne carbon tax would raise about $70 billion in revenue. I find it hard to believe that this would not have a measureable effect. It could well be that an even higher tax would be required to meet emission reduction targets, but $100 per tonne would be tougher than just about any other jurisdiction.

I think one way to mitigate the pain for exurban areas in to put in place a land value tax as well, which would also tend to hit the urban hippies harder than the suburban middle class. Also, a full land value tax would offset the property value impact of a carbon tax.

Frances: as much as we demonize cars, I think we pay too little attention to the work involved in making urban living more affordable. If you’re going to get families to not only slash their living space, but also pay more per square foot, you have to think about compensating that trade-off. A 2000 sf home on a 75×50 lot gives you roughly 5000 sf feet of private living space. The dense option (say, a 1200 sf condo) is a 75% reduction. What do you get for giving up a private yard, a garden, quiet, low crime, a basement gym, and the inane pleasures of organizing your garage? A short walk to Starbucks and more expensive groceries? Whoo hoo. My point about dining out was not (just) to sidetrack into a discussion on food, but to give a concrete illustration of how this can be compensated. You can really can dine out 5 nights a week in Asia and (and maybe parts of Europe?) for the same cost as shopping and cooking at home, plus there’s no cleaning. Year over year, that’s an immense welfare gain in lost domestic drudgery, but then no one in Tokyo has to head out with their kids into -25 weather to get to the noodle shop. And, aside from the amenities, there’s just the fact that limited privacy is just a norm in that part of the world. How would that become a norm here?

My casual observation is that a certain amount of suburban expansion is fueled by graft and corporate welfare with the housing industry, and political willingness to ignore the immense future burden of infrastructure expansion in suburban areas. Why should exurbanites (who aren’t stupid) pay the price for correcting that? How do we construct political penalties for bad urban policy?

Shangwen: “And, aside from the amenities, there’s just the fact that limited privacy is just a norm in that part of the world. How would that become a norm here?”

I think it would take at least a couple of generations. Notions of personal space are subtle and deeply ingrained e.g. how far apart people stand when they’re talking.

Frances,

I think much of the reason a greenhouse gas tax is such a hard sell in the exurbs is that so many people portray it as a horror story of fundamental lifestyle change. E.g.: “A carbon tax works because it makes commuting from the exurbs prohibitively expensive.” or “the change that is needed for Canadians to embrace higher density as a norm”. Neither of those statements, nor any of the endless variations on them, is particularly accurate. As somebody pointed out above, even a tax of $100 per tonne wouldn’t make life in the exurbs infeasible, and a realistic GHG tax would more likely start at something more like $20 per tonne. So, you get a more fuel efficient commuting vehicle, you try to telecommute a couple days a week if you can, and maybe you learn to program the fancy thermostat you bought a few years back. And, yes, you pay a bit more in total energy costs, so you have to cut back a little on your total consumption. What you don’t do is bulldoze your house and move into a monk’s cell in the city core. If you tell people that the whole purpose of a GHG tax is to wreck their lifestyle, of course it will galvanize them into opposition. What else would you expect? However, since that statement happens to be untrue, why on earth would you tell them that?

It would be a lot better to start with your figure above (which suggests that per capita emissions top out at about 13 t/yr) and observe that that equates to a couple hundred bucks per person per year (assuming that they don’t do anything at all to reduce emissions). From there you can talk about the costs of climate damages, and you can have a conversation about whether it’s worth a couple hundred bucks a year to avert them. I bet you’d get a very different response if you approached it that way.

Patrick, I think the estimates I’ve seen are around $250 – $300 per tonne. I don’t think we’ll necessarily see huge changes in behaviour. We are likelier to see big changes in technology. Increased adoption of electric cars, rather than a reduction in driving. More nuclear power and less coal/gas rather than drastically reduced electricity consumption. More cogen for process heat. All these things require higher fossil fuel prices to become economic.

There’s even technology to produce carbon negative (producing and burning results in a net reduction of CO2 in the atmosphere) gasoline through biochar sequestration.

Changing/fixing urban form is probably not going to result from a carbon tax. For that, I think you’d need a land value tax to reward higher land-use efficiency.

Per capita GHG production is around 23 tonnes per capita (CO2e). So $100 per tonne would add up for a family of four, say. Of course, a great deal of that happens in the commercial/industrial sector.

I don’t think that’s news to most people commenting, but it’s worth emphasizing:

But if carbon taxes don’t cause fundamental shifts in the way people live, are they likely to have a substantial impact on emissions?

This question is precisely why the case for a carbon tax is so compelling. If the tax fails to reduce emissions, then the Harberger triangle has height zero, and there’s no dead-weight loss. In other words, perfect efficiency is the worst case possible outcome of a carbon tax. Any reductions in emissions are just gravy.

Patrick & Andrew,

$250 – $300 per tonne is pretty high, unless you’re talking mid-century or later, or about a really tight CO2 constraint. By way of example, I’m looking at a run that ends the century at 550 ppm CO2 (usual caveats about model assumptions, etc. apply), and the tax starts at $12/tonne in 2020 and doesn’t reach $100/tonne until 2065. Those are 1990 dollars, so you have to apply an inflation correction if you want today’s dollars, but you’re still not looking at $250/tonne taxes any time soon.

As you say, by the time the tax gets really high, hardly anyone is paying it because GHG-intensive technologies have basically been driven out of the market. For example, carbon capture and storage technologies pretty much set a ceiling on the price of electricity; it can never go higher than the cost of a coal plant with CCS. If GHG taxes try to push it higher than that, then everybody just converts to CCS.

Is that a study from 1990? I wonder if it factors in convergence in per capita carbon emissions with the developing world increasing emissions.

I wouldn’t worry about $250 vs $100 as the upper limit of carbon taxes. We should just get to $40 and re-evaluate based on the effect that has. I like the idea of a citizen’s dividend as a way of building a constituency for otherwise unpopular ideas like a carbon tax and land value tax. I would maximize the visibility of the dividend (big shiny cheques in the mail on a regular basis), while burying the carbon tax in the price of goods. I think it could end up being fairly popular. You could even boostrap it with initial unfunded dividends and tell the public that they are going to stop unless a carbon tax is put in place to fund them sustainably.

“I am not sure that this is doable. What incentives do you offer? Subsidize energy efficiency? This might just lead to more consumption as people have to pay less to do something with an equivalent amount of energy – compensate by helping to pay for twice as much efficiency in cooling your house?”

You don’t neccesarily need to offer energy related compensation. You might just say, we’re going to take any revenue from the Carbon tax on and spend it on the Exurbanite so that the package of taxes and spending is palatable to them, i.e., compensate the losers from the imposition of carbon tax – just as California combines a package of road tolls and public transit). I like the suburban transit idea, since it would largely benefit suburbanites (although, to be fair, increasingly you see communiting from the downtown to the suburbs), but not in such a naked way as to be politically unpalatable (compared to something really crass like, “we’re going to give all the money to residents of the 905”).

“Or, for cars, now that engines are more efficient, we are building bigger and more powerful truck like vehicles, consuming the same amount of fuel, but for more car/power consumption per drop.”

But, let’s face it, that’s also a likely result of a carbon tax. After all, that’s been the result of rising gas prices since the 1960s. Yes, prices have gone up, but so has fuel efficiency and power, meaning that people can drive more and bigger vehicles. In fact, the likely result of carbon tax on the exurbanites is to switch from an SUV to an SUV with cylinder de-activation or a hyrid engine. A carbon tax will only change urban form/lifestyle if the perceived benefit of that form/lifestyle is less than the cost of using alternative, less carbon intensive, technologies to replace existing technologies.

I think this is a point that both sides in the carbon tax debate tend to miss.

“

There’s this from IPCC. They seem pretty optimistic about emissions reductions resulting from very modest carbon taxes of 30-50$ per tonne.

http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg3/en/ch11s11-6-3.html

Andrew,

I’m assuming your question was directed at me. The run I quoted was one that I did earlier this week. It’s in 1990 dollars because that’s what the model uses, and it’s a lot easier to convert the output than to revise all of the data that goes into the model. I should also mention this is $/tonne of carbon, while the IPCC report you linked to (which is itself based in part on runs from (an older version of) this same model) mostly quotes $/tonne of CO2.

I totally agree with you about getting to something in the $40 or $50 range and reevaluating. One of the depressing things about working in this field is that you see firsthand how much mitigation we could do with a very modest change in policy. Yet, we can’t get there because when it comes to climate the only two positions people seem to be able to wrap their heads around are “not a real problem” and “apocalyptic”. Anyone advocating practical solutions gets lost in the din. Even the people who think they are trying to help just wind up making things harder.

According to the Pembina Institute, 7% of Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions came from oil sands in 2010 (http://www.pembina.org/oil-sands/os101/climate#footnote10_epyxz63). I don’t know what their positions are now, but historically energy companies have not opposed carbon taxes or carbon pricing. See, e.g., Shell Oil noting in this article that their ought to be a carbon price: http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/industry-news/energy-and-resources/president-of-royal-dutch-shell-canadian-division-urges-carbon-price/article4534929/#dashboard/follows/

Oil sands do produce more greenhouse gases than conventional oil production, but I am not sure that they would be the worst hit industries by a carbon tax, or that the political opposition would come there as opposed to from the exurbs.

Carbon taxes will primarily bite in winter heating bills, industrial uses of electricity.

http://oilsands.alberta.ca/climatechange.html

In AB, oil and gas & oil sands are the biggies (41% of emissions in 2010), followed by coal fired electricity (20%), and transportation (16%).

Switching away from coal seems like a no-brainer. Oil sands is harder. They already use NG, which is extremely efficient and clean. They just use a lot. There was talk of building a nuclear power plant for generating the steam they need, but that idea died. I can’t really blame people for not wanting a nuke plant.

You should. Nuclear power is clean and safe–it has killed fewer people per kWh of energy than most other sources. Coal and other fossil fuels are like a Chernobyl every few days in terms of deaths, illness and environmental damage.

The problem with the nuclear plant was just the enormous capital cost associated with it. Also the production of the oil sands results in extraction of the natural gas as well. If the oil sands don’t use the natural gas they produce they have to send it somewhere else to be used. And of course at the moment there is something of a supply glut in natural gas because of the advent of fracking, so that’s problematic.

I am not sure how useful the intra-Alberta numbers on the oil sands are Patrick insofar as pricing the carbon isn’t something that individual Albertans would pay directly – the payment would be by the corporations who develop the oil sands all of which have international scope in their activities and ownership. The carbon is produced here, but it is produced by and for the benefit of people well beyond Alberta’s borders.

I will only add that despite the issues in the exurbs I think a carbon tax is very important and desirable. As an example, the oil sands are likely to be worth developing economically, but let’s make sure we have included all of the costs – carbon, reclamation and most essentially the uncertainties inherent to the whole exercise. Do we know how this will all turn out? I don’t think so, and let’s be honest about that in deciding whether or not to develop it.

Alice (Woolleylaw) – I always think of the view from the top of the hill just above Dawson City – the way the whole landscape had been transformed by placer mining as far as the eye could see. It’ll never ever be the same again.

I’m told things have changed.

But human nature hasn’t, nor have the economic incentives that have led to massive environmental destruction in the past.

From an economics standpoint I don’t see why the fact that a carbon tax would adversely affect the exurbs is a bad thing. If the goal of a carbon tax is to reduce carbon output and the tax causes high carbon outputting exurbers to pay for their emissions or reduce them, isn’t that an accomplishment of the tax? I’m not sure why the effect on the exurbs is seen as a bad thing when the effect on high carbon emitting companies isn’t. Also as many have pointed out, a carbon tax would have a mostly minor effect on exurb living, so the issue seems kind of moot.

“If economists want to sell carbon taxes, we have to face up to their distributional consequences.”

I’m not sure why this is, other than for political reasons. When we punish a bad behaviour we don’t then try to compensate the people who are punished. If the punishment is seen as to harsh we need to reduce the punishment, not pay people to put up with it.

Politically this is a charged issue, but from an economics standpoint I don’t see why

Frances is raising a red flag over the effect to the exurbs.

Frances: 90% of the oil sands are too deep underground to be strip mined. SAGD and other in-situ recovery methods are nowhere near are destructive as strip mining. I don’t think you have to worry too much about the physical destruction of Northern AB. They’ve pretty much already destroyed about as much as they will.

Jason: Why is living in the ‘burbs bad behaviour in your books? One can equally make the argument that people in the ‘burbs shouldn’t be subsidizing the enviro-fetishism of the latte sipping class when there are coal fired power plants to be replaced and hyper-efficient cars to be developed.

“while burying the carbon tax in the price of goods”

Yeah, but the cost of a carbon tax can be borne in different ways – that assumes that the incidence will be borne by consumers. What if it isn’t? How do you “bury” the impact of a carbon tax, when a manufacturer closes an energy intensive plant because it’s no longer cost-effective to operate it?

This goes to the distributional impact of a carbon tax. If it’s reflected in higher prices, then, everyone pays to a certain extent (though, not if there are systematic differences in energy intensity of consumption). But maybe it translates into lower employment/wages in particular industry/sector/region (though, with labour mobility, presumably in the long run that cost would be borne in other industrys/sectors/regions, as workers reposition), or if the incidence if borne by labour and not capital, than it has distributional implications that raise political ones.

I think part of the problem with the environmental movement, and why they’ve had so much trouble getting traction on this issue, is they tend to ignore or assume away the distributional implications of their policies. That flows from the underlying “retributivist” (great term) nature of modern environmental ideology, reflected in the polluter pay principal, which results in a lack of empathy or concern for the welfare of people who benefit from pollution. But it’s politically disastrous, because those are the people whose support you need to effect political change.

“Why is living in the ‘burbs bad behaviour in your books? One can equally make the argument that people in the ‘burbs shouldn’t be subsidizing the enviro-fetishism of the latte sipping class when there are coal fired power plants to be replaced and hyper-efficient cars to be developed.”

It’s not that living is the ‘burbs is bad behaviour it’s that, as shown in the map, people living in the ‘burbs tend to output more green house gas. Since we are taking polluting as a negative externality, a cost should be paid for it. I don’t think we should be taxing the ‘burbs so much that living there would be impossible to afford, but taxing carbon so that there is a general downward trend in emissions is the end goal. Also a carbon tax wouldn’t just affect the ‘burbs It would also raise funds from coal power plants and other industrial polluters and the effect on industrial polluters would be much more significant.

But Bob, how do you identify those who would have benefited from pollution? How do you identify the would-have-been coal miners?

Andrew F – Maybe you only need to identify those who currently benefit and who will stop benefiting when the policy regime changes. They are the ones who will resist change. The would-have-been coal miners don’t know they what they missed-out on, so they don’t get angry and vote for the candidate who says climate change is a vast conspiracy (or whatever other silliness).