At a family party in the Toronto exurbs, right on the outer edge of the 905 zone, one of my favourite cousins cornered me. "You're an economist," he said, "tell me why you think carbon taxes are a good idea."

My first thought was to sidestep the issue. "They're only a good idea," I said, "if you think global warming is a problem. If you don't think people consume too much by way of fossil fuels, then there's no need for a carbon tax."

Then I tried the economic freedom line: "A carbon tax makes fossil fuels more expensive, so people have an incentive to consume less. The great thing about them, though, is that people have a choice about how to cut their consumption."

"Think about the alternative," I said, "Do you really want a bunch of new regulations, people saying what you can and cannot do? This way there's no need for a big government bureaucracy, and people decide what's best for them."

Neither of these arguments made the slightest impression on my cousin. "I don't believe this talk about revenue neutrality," he said, "there won't be cuts to other taxes. The government will just take the money and spend it on useless things like your salary." [Note: he denies saying this.]

This was a low blow, especially coming from someone who also lives off taxpayer dollars (though I suspect, knowing my cousin, that getting this jab in might have been the whole point of the conversation). There was another, more persuasive, point he could have made: just look around you.

In the exurbs, it's possible for a single-earner family with a decent middle-class job to buy a home big enough to host a family party, with a two car garage, a garden, and a luxuriously large kitchen.

A carbon tax works because it makes commuting from the exurbs prohibitively expensive. Leaving the exurbs means not having a garage big enough to work on restoring a 1966 Mustang. It means giving up the backyard pond and the garden and the barbecue. It means taking a capital loss on a home that is no longer desirable, given the cost of getting to work.

If economists want to sell carbon taxes, we have to face up to their distributional consequences. In Toronto, there are (roughly speaking) two groups who would gain from a carbon tax.

The first group is those who cannot afford to use carbon. According to this study, the Torontonians with the smallest carbon footprint are those who live in the high rises and housing projects of East York. They have small living spaces, hence low heating costs, and take public transit. A BC-style carbon tax, which includes a refundable tax credit for low income individuals, would make these people better off.

The second group that gains from a carbon tax are those prefer a lower carbon lifestyle, and can afford to indulge their preferences. They're the people who think of their car (if they own one) as a recalcitrant, overpaid, employee, but pamper their bicycle with special botanical chain oil from Mountain Equipment Co-op. They live in Toronto's waterfront condos, or in areas like little Italy. A reduction in income or consumption taxes, financed by an increase in carbon taxes, would be a clear gain for the higher income, lower carbon demographic.

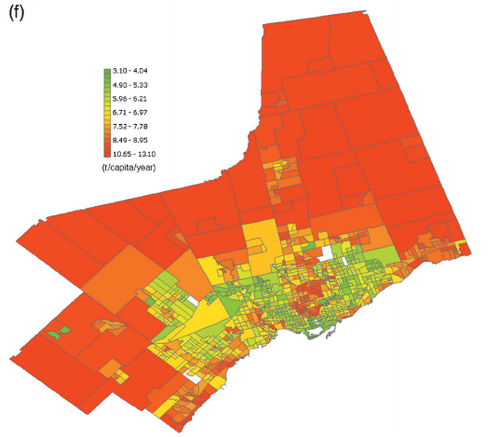

The biggest losers from a carbon tax are people like my cousins in the exurbs. The map above, taken from a paper by VandeWeghe and Kennedy, highlights the parts of Toronto with the highest per capita carbon consumption in red. These are place where people live in reasonably large houses, and commute long distances to work, generating whopping carbon footprints.

The whole purpose of a carbon tax is to discourage this type of lifestyle. But I can see why people are reluctant to give it up. Except for the commute, it's great. The streets are quiet, clean and friendly, and there's lots of green space near by. For a person who wants a garden and ample living space, the alternative housing options in the same price range are clearly less desirable: a small, unrenovated bungalow in Scarborough, say, or a downtown condo.

The most valuable lesson economics teaches is that people aren't stupid. Greg Mankiw might say that the basic case for a carbon tax is “is so straightforward as to be obvious.” Here's something else that's obvious: carbon tax hurt in the exurbs.

This cousin sounds like a real gem! He’s really made the case for why he should be favored by tax law; how could anyone want to harm him considering his charm and sunny disposition?

Anyway, it would show another side of this if the distributional impact were shown by graphing the amount of carbon tax paid against income or wealth. Your quip about organic bicycle oil notwithstanding, people in the exurbs tend to be wealthy and people who live in the city without cars are often families that are struggling. I don’t see anything wrong with asking rich people to fork over a little more for one particularly destructive aspect of their lifestyle.

Just because it’s the status quo doesn’t mean its policies don’t have a distributional impact. The current policies with their own distribution impacts were set up because people living in the exurbs are more likely to have famous economists for cousins. The exurbs (in the US, at least) get subsidized so many ways that the people who live there can’t even count them anymore and assume they’re rugged individualists.

Taking away that privilege is going to make rich people mad in the same way that taking away any of their money makes them mad. But, if anything, it’s a reason to go ahead with the carbon tax because global warming has a distributional impact of it’s own: people with less money are more likely to lose their homes, lose access to food and water, and lose their lives.

Putting the distributional impacts side-by-side – rich people take a hit to capital and maybe have to switch houses vs. poor people lose everything they have – it’s not hard to pick.

Alex: “people in the exurbs tend to be wealthy and people who live in the city without cars are often families that are struggling”

That’s not so true in Canada as it is in the US – the exurbs here are much more middle class than rich (E.g. in Vancouver the serious money is in Shaugnessy or West Vancouver, not Langley or other places up the valley). Though as the saying goes: hell hath no fury like the middle class in defence of its privileges.

Jason: “Politically this is a charged issue, but from an economics standpoint I don’t see why

Frances is raising a red flag over the effect to the exurbs.”

Because from an economics standpoint, as well as a political one, the distributional consequences of policies matter. Suppose one believes that transferring money from the rich to the poor increases social welfare (because, say, the poor get more benefit/enjoyment from a dollar of income at the margin than the rich do). Then distributional consequences make some policies more attractive, e.g. a carbon tax on airfares or subsidies to public transit. Distributional consequences make other policies less attractive, e.g. reductions in the top rate of income tax, tobacco taxes.

Bob: “A carbon tax will only change urban form/lifestyle if the perceived benefit of that form/lifestyle is less than the cost of using alternative, less carbon intensive, technologies to replace existing technologies.”

I think that’s worth another blog post.

at risk of not helping, the AR4 WG3 carbon price range of 30-50USD is based on stabilizing CO2 at 450ppm, a level more recent work has determined to be very dangerous. the AR5 WG3 is due within the year.

an immediately obvious consequence of the 2007 350ppm stabilization finding was that a significant amount of equipment needed to be removed from service as quickly as possible, and that markets would have a hard time getting the rich world to cut its GHGs in half within a generation.

I don’t understand why – at least as you reported it here – you didn’t point your cousin to why we’d want to reduce emissions in the first place. You say what a tax what do, or why it would be the best way to do it – but not why. The social cost of carbon is positive in every single assessment by now. Symbolically speaking, your cousin continuing his lifestyle does more damage to someone else than it does good for him.

I understand that the Pigovian framework (which implies the tax as a consequence a negative net present value of further emissions) might bother him: those affected are in another place, in another time – it’s difficult to care. I understand that he might have doubts that a tax would be effective, as the various policy settings around the world are certainly not first-best, to say the least. I understand that he could have some Buchanan- or Coase-inspired critique. But then, none of these possible issues is even raised here, while the reasoning underlying the idea of a carbon tax is not even alluded to. The inevitable result are odd sentences like “The whole purpose of a carbon tax is to discourage this type of lifestyle.”, as if there was not more to the story – and it’s not only not in this sentence, it’s nowhere. That is, for example, the consequence of a BAU emissions scenario: the lifestyles of strongly emitting countries entail damages to someone else (before those damages would eventually come to them) without taking it into account. It’s a negative externality. And for some reason, you didn’t bother to tell your cousin about it.

Martin “I don’t understand why – at least as you reported it here – you didn’t point your cousin to why we’d want to reduce emissions in the first place.”

This particular cousin really is a good guy – he’d drop everything to help me out if I was in any kind of trouble (even though he’d probably have a laugh at my expense along the way). But, honestly, launch into a lecture on global warming at a family party? No way! I value family harmony too much for that.

hapa – I actually had lunch with an environmental economist the other day who was challenging the conventional orthodoxy on carbon taxes, saying he didn’t understand why every economist he knew was so keen on them. Perhaps for some of the reasons you’re describing.

fran – i can’t speak for him but i do find it confusing that so many economists prefer to reframe/reject climate science than to let other means of action share the pedestal with price signals.

The economists who are proposing a carbon tax are not rejecting the climate science; if they were, they’d be proposing to do nothing.

Here are a couple of posts I did for Maclean’s outlining why carbon taxes (or market-based measures) are preferred: [1], [2]

stephen – i apologize, i followed an american link into your canadian carbon conversation and didn’t know the state of play. i was not talking about the least-cost way for incremental improvements. instead i’m talking about how fast & deep we the rich industrial peoples must cut carbon in order to manage risks, and a tendency i’ve seen among even thoughtful economists to prefer older climate data when new data indicates the task is much larger than carbon pricing can accomplish.

Andrew: “But Bob, how do you identify those who would have benefited from pollution? How do you identify the would-have-been coal miners?”

On an individual level, you probably can’t – there are people who cycle in the burbs and people who drive SUVs in downtown Toronto. But Frances’ original post make a compelling case that the impact of a carbon tax would be felt more keenly in exurbs, because they emit more carbon. So you’d target spending at the exurbs. In any event, politicians shouldn’t have a problem identifying the people to target – they’re going to be the ones most adamantly opposed to a carbon tax.

Frances,

re agricultural policy – don’t you just really mean planning discipline. In Germany, there are regional planning authorities. Local politicians can’t just unilaterally decide to change rural/recreational land into housing.

Land use is another “tragedy of the unregulated commons” story. Land value really is dominated by externalities, and that value can often be expropriated by the ruthless.

Where I live on the edge of Frankfurt is in a way quite funny (to me coming from the sprawl city of Sydney originally). Frankfurt is officially a city of about 600,000 people. The city where I live is of about 60,000 and is fairly self contained (be very wealthy) with a large shopping center and even couple of live theatres and a cinema. But Frankfurt is just the other side of the autobahn, and there is another city the other side of another autobahn. And between each of these cities is a single cultivated field either side of the respective autobahns. This means, that everybody in the smaller cities can walk or cycle to fields from their home (the fields are unfenced with public paths through them). This is small thing, but it makes a huge difference (it also means that there is space to expand the infrastructure connections if need be without very expensive eminent domain confiscation and destruction of property).

David Brin, once speculated that after the destruction on Haiti from the earthquake, they should have reserved some land for infrastructure. The ability to scale infrastructure without huge extra investment is a thing of no small value. I’m always somewhat incredulous that humans haven’t found a better way to install and maintain infrastructure such as gas pipes, water pipes, communication and power cables than to continually dig up the street and then refill it. We need to plan this better – even if planning has become a dirty word. Not everything self-organizes in an ideal way.

K: I like the way you think. I think you have the politics right.