The OECD Health Data 2013 final update numbers are out and for the first time average life expectancy at birth in the OECD countries (numbers for 2011) exceeds 80 years at 80.1. This represents a gain of ten years since 1970. When life expectancy for men and women at age 65 is examined, there are substantial gains here also. The life expectancy of females at age 65 in the OECD in 1970 was 15.8 years and grew to 20.9 years by 2011. Meanwhile, over the same period, the life expectancy of males went from 12.7 years to 17.6 years. The OECD notes that high per capita income is associated with higher life expectancy though many other factors play a role. I guess an interesting question is what some of these other factors in the life expectancy health production function might be and how important medical resources are.

Take a look at the following local polynomial smooths of life expectancy at birth on assorted medical resource variables. The data is from 2013 edition of the OECD Health Data and the figures present the relationships using data only for the year 2011. Figures 1 and 2 show that more physicians and nurses per capita is positively correlated with life expectancy at birth. However, numbers of physicians and nurses says little about the intensity with which their services are available. Hence, a physician consultation variable is used in Figure 3. However, Figure 3 shows a more variable result when per capita physician consultations is plotted against life expectancy. Seeing your physician more often seems like a bit of a roller coaster experience.

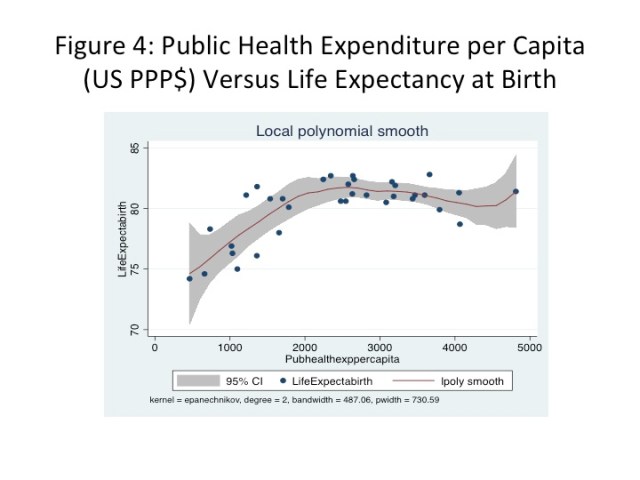

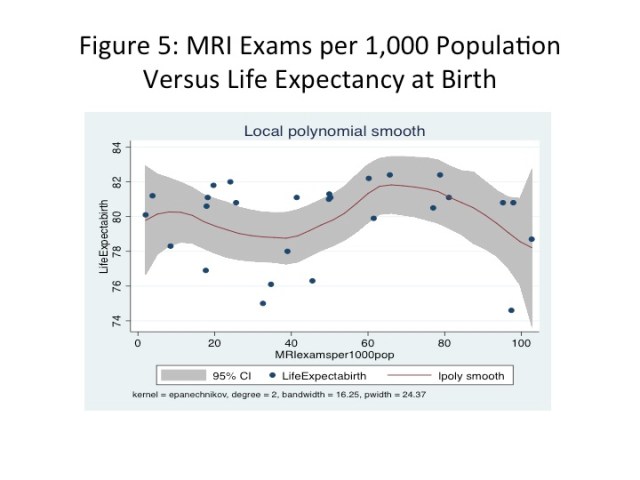

How about resource expenditure? Figure 4 plots life expectancy as a function of public health expenditure per capita. Here the results show a positive relationship up to about $2500 and then a slight decline. More public health expenditure per capita seems to eventually yield diminishing returns. Figure 5 looks at the role of technology – the number of MRI exams per 1,000 of population is plotted against life expectancy and it yields a roller coaster similar to physician consultations per capita. Based on Figures 3 and 5, I would have to say that seeing the doctor more often and having more scans may not always be conducive to a longer life. Finally, the accompanying table presents a number of assorted simple regressions to see what variables might best explain life expectancy using the 2011 OECD data. It would appear that per capita income and per capita public health expenditure are important variables.

In the early 1960s, average life expectancy at birth in the OECD countries was 68 years and has now reached just over 80 years. Over a fifty-year period, we have added 12 years to life expectancy at birth in the developed countries. In Canada – where life expectancy at birth is pretty close to the OECD average (81 versus 80.1) – the gains since 1970 match the growth for the fifty years previous. In 1931, life expectancy at birth for Canadians was about 61 years while by the early 1960s it was 71 years and now is at 81. Over 80 years, we have added about 20 years to life expectancy at birth in Canada and one expects this is similar across the OECD. When it comes to life expectancy as a health production function, we don’t seem to have reached the peak of the function yet. The growth of life expectancy at birth has been a persistent phenomenon and based on past performance I expect the next 50 years will add yet another decade to average life spans but probably little additional understanding as to what the key factors are.

// <![CDATA[

// <![CDATA[

// &lt;![CDATA[

// &amp;lt;![CDATA[

// &amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[

// &amp;amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[

// &amp;amp;amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[

// &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;lt;![CDATA[

var sc_project=9080807;

var sc_invisible=1;

var sc_security=&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;4a5335bf&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;;

var scJsHost = ((&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;https:&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot; == document.location.protocol) ?

&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;https://secure.&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot; : &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;http://www.&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;);

document.write(&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;lt;sc&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;+&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;ript type=&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;#39;text/javascript&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;#39; src=&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;#39;&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot; +

scJsHost+

&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;statcounter.com/counter/counter.js&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;#39;&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;gt;&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;lt;/&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;+&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;script&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;gt;&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;quot;);

// ]]&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;gt;

// ]]&amp;amp;amp;amp;gt;

// ]]&amp;amp;amp;gt;

// ]]&amp;amp;gt;

// ]]&amp;gt;

// ]]&gt;

// ]]>

// ]]>

Related articles

Very interesting Livio! The $2500 marker looks familiar to me…I recall seeing other OECD-dervied analyses where the impact of healthcare spending on longevity and morbidity peaked in the 2500-3500 range, then flattens.

Part of the challenge is that healthcare is not consumed at a consistent dosage over the life course–we use it more in periods of either high risk or high morbidity (infancy, pregnancy and childbirth, frail old age, the terminal year, and when seriously ill). Most people consume public healthcare very irregularly over the lifecourse (surgeries, major illness, pregnancy, etc) but consume private healthcare more consistently (pharmaceuticals, dentistry, etc). You are essentially asking a lifetime dosage question.

There is some recent US evidence (sorry Stephen–mixing countries again) that morbidity in old age is becoming compressed into an extremely narrow timeframe at the end of life, contrary to the historical experience and current perception that age is a long and painful decline. I think the relationship of spending/consumption to longevity is that there are a small number for whom care significantly extends life, but for the majority most is accounted for by socioeconomic improvement, while there is very intense utilization associated with small gains in the final years.

I think it would be worth to take a closer look at how these mortality tables (wiki/Life_table) are constructed, and how then a LE is derived. And how those are impacted by migration of various age and social economic background.

Further it is worth to look at the non-universal health care states USA and Mexico, and the special situation of eastern Europe.

Thanks for the reference to the paper Shangwen. It is a very recent NBER paper-great! Ultimately, I think the data as I used it is too coarse to get at differences in lifetime use.

Genauer-the impact of differences in health systems is a good point. As for the life expectancy numbers-the impact of migration on those numbers is an interesting aspect also. The young tend to migrate and they are generally in better health than older people which aside from affecting life expectancy numbers should also affect health expenditures.

just accounting for US/Mex (non universal health care) + Eastern Europe (EE)in a hyper simplistic black/white Zero /one fashion accounts for 60% of the variation:

mean factor

Variance 81.10 -4.36

6.01 2.41 0.60 .=r^2

country LE delta model US & EE

Australia 82.0 0.9 81.1 0.00

Austria 81.1 0.0 81.1 0.00

Belgium 80.5 -0.6 81.1 0.00

Canada 81.0 -0.1 81.1 0.00

Chile 78.3 1.6 76.7 1.00

Czech Republic 78.0 1.3 76.7 1.00

Denmark 79.9 -1.2 81.1 0.00

Estonia 76.3 -0.4 76.7 1.00

Finland 80.6 -0.5 81.1 0.00

France 82.2 1.1 81.1 0.00

Germany 80.8 -0.3 81.1 0.00

Greece 80.8 -0.3 81.1 0.00

Hungary 75.0 -1.7 76.7 1.00

Iceland 82.4 1.3 81.1 0.00

Ireland 80.6 -0.5 81.1 0.00

Israel 81.8 0.7 81.1 0.00

Italy 82.7 1.6 81.1 0.00

Japan 82.7 1.6 81.1 0.00

Korea 81.1 0.0 81.1 0.00

Luxembourg 81.1 0.0 81.1 0.00

Mexico 74.2 -6.9 81.1 0.00

Netherlands 81.3 0.2 81.1 0.00

New Zealand 81.2 0.1 81.1 0.00

Norway 81.4 0.3 81.1 0.00

Poland 76.9 0.2 76.7 1.00

Portugal 80.8 -0.3 81.1 0.00

Slovak Republic 76.1 -0.6 76.7 1.00

Slovenia 80.1 -1.0 81.1 0.00

Spain 82.4 1.3 81.1 0.00

Sweden 81.9 0.8 81.1 0.00

Switzerland 82.8 1.7 81.1 0.00

Turkey 74.6 -2.1 76.7 1.00

United Kingdom 81.1 0.0 81.1 0.00

United States 78.7 2.0 76.7 1.00

OECD AVERAGE 80.1 -1.0 81.1 0.00

I knew that there was a bimodal distribution, when I saw the plots,

and teasing Livio a little bit, there are way too many outliers from your 95% confidence intervals.

My latest analysis, completely ignoring all input from the OECD, explains 95% of the variances, to well within a noise level of 1 year.

Just health care coverage(for Mexico, USA, Turkey), bringing it up to 90%, and crude quarter fraction assignments to eastern Europe factors, going to 95%, commented individually, and explained in some sentences below. Please download the data, and challenge my assignments, the remainder is just noise.

Being a neighbor to German speaking Europe (Poland, Czech, Slovenia) is very healthy and to German culture (Chile) too. Just the data talking : – )

I have the advantage to have probability distribution plots way more complicated for years for breakfast as part of my job.

wiki/Gompertz-Makeham_law_of_mortality shows that you can characterize mortality rates with really remarkable precision into a general risk, shown at low age, and an accumulated wear & tear showing up at older ages, curves with just 3 robust parameters

These numbers are derived from mortalities from people with pretty different (wealth) histories

Eastern European countries like Poland had food rationing into the 1980ties, with meat rationing ending 7/31/1989 (http://www.nytimes.com/1989/07/31/world/poland-to-end-rations-and-food-price-freeze.html)

There was the bitter joke: What does a polish hamburger look like?: bread stamp / meat stamp / bread stamp

East German school classes in the 1980ties were ordered to march into the lignite fields, to hammer away the ice to keep the power plants going. And before we develop any hubris here, what would you do? Chipping a little away of the life expectancy or to have frozen people lying in the streets and houses?

They did not have hard currency to buy western German made filters for soots, sulfur oxides, etc. , producing high levels of air contamination.

This did ate away on our buildings, forests, health in large areas in west Germany as well.

They couldn’t buy anywhere enough oranges, citrones, were short on pharmaceuticals, hospital supplies. It still brings tears into my eyes.

the data table

81.27 -5.63 -17.49

6.01 0.322 0.95 .=r^2

country Life expectancy, Total population at birth, Years delta model EE non health care outlier comment

1 Australia 82.0 0.7 81.3 0.00

2 Austria 81.1 -0.2 81.3 0.00

3 Belgium 80.5 -0.8 81.3 0.00

4 Canada 81.0 -0.3 81.3 0.00

5 Chile 78.3 -0.2 78.5 0.50 how would you rate the SA Pickelhauben?

6 Czech Republic 78.0 -0.5 78.5 0.50 high GDP for EE, between Germany and Austria

7 Denmark 79.9 -1.4 81.3 0.00 hmm, lower despite high minimum wage

8 Estonia 76.3 0.7 75.6 1.00

9 Finland 80.6 -0.7 81.3 0.00

10 France 82.2 0.9 81.3 0.00

11 Germany 80.8 0.0 80.8 0.08

12 Greece 80.8 -0.5 81.3 0.00

13 Hungary 75.0 -0.6 75.6 1.00

14 Iceland 82.4 -0.3 82.7 -0.25 special rich resource place

15 Ireland 80.6 -0.7 81.3 0.00

16 Israel 81.8 0.5 81.3 0.00 no comment from a German guy

17 Italy 82.7 1.4 81.3 0.00 really, with the mezzo giorno

18 Japan 82.7 0.0 82.7 -0.25 Sushi?

19 Korea 81.1 -0.2 81.3 0.00

20 Luxembourg 81.1 -0.2 81.3 0.00

21 Mexico 74.2 -0.1 74.3 0.00 40% 0

22 Netherlands 81.3 0.0 81.3 0.00

23 New Zealand 81.2 -0.1 81.3 0.00

24 Norway 81.4 0.1 81.3 0.00

25 Poland 76.9 -0.1 77.0 0.75 close to Germany

26 Portugal 80.8 -0.5 81.3 0.00

27 Slovak Republic 76.1 0.5 75.6 1.00

28 Slovenia 80.1 0.2 79.9 0.25 Euro Area, separated in 1991

29 Spain 82.4 1.1 81.3 0.00 do we believe the better number with 15% immigration 200-2007

30 Sweden 81.9 0.6 81.3 0.00

31 Switzerland 82.8 0.1 82.7 -0.25 rich folks

32 Turkey 74.6 -0.2 74.8 1.00 5%

33 United Kingdom 81.1 -0.2 81.3 0.00

34 United States 78.7 0.2 78.5 0.00 16% 0

35 OECD AVERAGE 80.1 -0.1 80.1 0.20

I appreciate the additional material Genauer. I guess the next step would be to go beyond just one year of data as well as put in variables to capture institutional differences (eg. universal versus non universal health care systems) as well as regional variables. When combined with some of the other variables discussed in the post, it would probably up the explanatory power of the regressions substantially. I also would like a better health outcome indicator than just life expectancy.

maybe a useful comment:

I actually started the analysis with downloading the OECD data, Livio referenced, with the intent to do a nonlinear fit, started with health expenditure as % GDP, and then just veered off to things (health care coverage, eastern europe) which seemed to be obvious to me to account for.

I can still acount for other factors, provide intelligent excel sheets doing so, maybe via Livio, but found the total divergence really remarkable : – )

Livio,

I am thinking similar lines of thoughts.

I will work, based on the same excel sheet from OECD, a little longer, the multi year is inherently built it, make it useable, and then sent it to you, tomorrow, to hammer away it.

We are both looking for the same results, how much of what, nurses etc. do we need.

I provided some european, engineering input today.

And If I would believe, I am good enough alone, I wouldnt post here.

thank you Genauer!

If I look at your CI plots,

I think it is actually much easier, you just put the health care coverage into your analysis yourself.

US 16%, Mexico 40% from the wiki. The 5% for Turkey was my estimate for their kurd regions, but how to make that presentable? I got so carried away yesterday and forgot to copy it over here.

I remembered a recent “marginal revolution” thread “The Myth of Americans’ Poor Life Expectancy”

where somebody tried to explain the bad US data with car accidents and gun violence, but in a somewhat hairy way. Hmmm, how to separate?

To be an eastern european country, as a 0 or 1, you also easily do yourself too, and my gut feelings of relative eastern europeanness (that was the last number in my unreadable table above) are not exactly academic style. But I think taking into acount past GDP per capita would do something very similar, and would also be possible to apply for earlier years.

I am still puzzled with how I got the hunch with health care coverage and eastern europe. I have no idea, how one could get to that in a systematic approach.

It would be nice to know, whether all the stuff, MRI, paying nurses, physicians, hospitals has some calculable payoff.

With the LE data, I yesterday also looked up the CIA world fact book data, checking if the “outlier” denmark maybe a typo, and the CIA and OECD data differ by 0.6 – 1.13 years for the 5 countries I just picked. I thought about your comment, and I also dont have any better idea than LE.

The British use some “quality of life years” measurements in medical papers, trying to assess the impact of various treatment options.