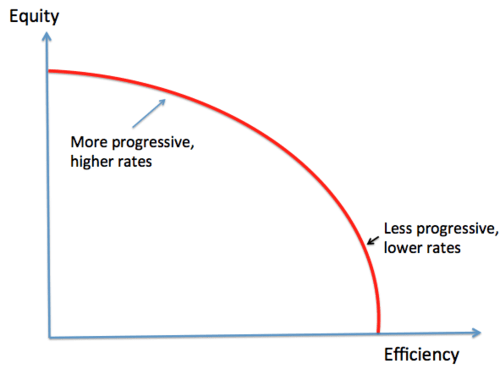

The ideal tax system reflects a compromise between two conflicting goals: equity and efficiency.

Equity requires that those who are able to pay more taxes do so. It means taxing the rich and giving to the poor, in thereby reducing inequality and ameliorating poverty. Hence equity demands relatively high marginal tax rates.

Efficiency, on the other hand, argues for lower marginal tax rates. Taxes are inefficient to the extent that they distort people's choices. But choices are made on the margin – to work an extra hour, to save an extra dollar. For example, when deciding whether to work overtime, a rational decision-maker will compare the pain of working longer hours with the gains from doing so. These gains are shaped by the tax rate on the last dollar earned. Hence what matters for efficiency is marginal tax rates.

Intelligent people disagree about how much efficiency should be sacrificed in the name of greater equity, and vice versa. Some favour higher rates and more progressivity; others place greater weight on efficiency, arguing for a broad tax base and a low tax rate.

But economists agree: tax reductions should deliver improvements in equity, or efficiency, or both. Income splitting does neither.

I am using the term income splitting here to refer to policies that allow a person to transfer money to his or her spouse for tax purposes. Income splitting reduces a couples' tax liabilities when one partner has a low income and other has a high income, because the income transferred to the low income spouse is taxed at that person's own, relatively low, marginal tax rate.

Income splitting reduces efficiency because it raises the effective marginal tax rate faced by the "secondary earner" – by which I mean the lower-earning of the two spouses. Suppose, for example, income splitting allows Ahmed to transfer $50,000 of his earnings to his partner Betty – an at-home spouse – for tax purposes. If Betty decides to enter the labour force, some of the tax savings achieved by income splitting will be lost. At the same time, Betty will have to pay EI and CPP premiums. Adding together the loss of tax savings and social insurance premiums, Betty will face a considerably higher marginal tax rate than she would have faced in the absence of income splitting.

One could note, of course, that Ahmed's effective marginal tax rate is reduced by income splitting. But the point is: the labour supply of "secondary earners" is much more elastic than the labour supply of primary earners. What the vast labour economics literature on this subject tells us is that, if Ahmed's marginal tax rate falls, he probably won't change his labour supply very much. Betty, on the other hand, is much more likely to be affected by a change in her marginal tax rate.

Income splitting reduces the marginal tax rates of people who aren't very sensitive to changes in tax rates, and it increases the marginal tax rates of people who are sensitive to changes in tax rates. That's why it has efficiency costs.

Income splitting also compromises equity. One interpretation of equity focuses on the vertical: relieving poverty and reducing inequality. The benefits of income splitting go primarily to higher income Canadians (see, for example here), so it does nothing for vertical equity.

Some might say income splitting promotes horizontal equity, because it allows single earner couples and dual earner couples with the same total income to pay the same total taxes.

Yet the proper basis for making equity assessments is ability to pay taxes. A single earner couple always has the potential to increase their income by having the second spouse enter the labour force – this is how Canadian families have been maintaining their standard of living in the face of declining male wages and rising house prices for the last several decades. The earnings capacity of the single earner family at $100,000 is greater than the earnings capacity of the dual earner family at the same income level – and with greater earnings capacity comes greater ability to pay taxes.

Moreover, the single earner couple enjoys the benefits of having an at-home spouse – having someone there when the children come home from school, someone to stay home with the children when they're sick, someone with time to organize all the stuff in life that needs to be organized.

Dual earner couples have a lower standard of living than single earner couples at the same income level. Therefore horizontal equity requires that they pay lower taxes.

Income splitting delivers neither equity nor efficiency benefits. Also, income splitting at the federal level would create pressure for income splitting at the provincial level, further compromising the ability of provinces to balance their budgets.

It's a bad idea. My message to the government: don't do it.

“More to the point, if the conservative governments is trying to help families with children, why on earth would they pursue a policy where most of the benefit accrues to families who need it the least.”

I think we can say that (gov’t trying to help families with children) w.r.t. UCCB and other benefit payments.

Can’t say that w.r.t. daycare subsidies and deductions, since they don’t apply to 30% of families with young children who look after them by themselves. We could say that w.r.t. helping families put a 2nd (or in the case of a single parents, the 1st) spouse back to work. Where is the objective for daycare stated anyway?

Why do we (to use my 1% example) help a $400K income family put a 2nd spouse back to work? Makes sense, I guess, if the only objective is to get the 2nd spouse back to work. Just don’t dress it up as it being for the kids.

Why do we let a retired bank (or Nortel) president save $30K through pension splitting? Again, can you provide a reference/link where I can look it up?

In the case of a the free $2,100 ghost spouse credit we provide a single parent, I can see that the government wants to tax the single parent the same as a 1-earner couple family, even in the case of a $400K income.

We could perhaps say that parental leave is to benefit the child, but this is an expensive (52-week) benefit.

There are probably a few goodies that I left out, but you see a pattern, which is there is a targetted benefit for just about every type of family with young children except the type that looks after their own kids.

If it’s really for the kids, then why is the only thing thing that accrues exclusively to this group, is a $7,300 tax penalty? Is that all this group deserves from the tax system? Currently, the answer is apparently YES.

So, as expected, the Tories gutted their proposal to allow income splittting by capping the maximum savings at $2K. Also as expected,they structured it as a credit, so that it doesn’t affect provincial revenues. They’ve increased the UCCB and extended a limited UCCB to children over 6 and increased the maximum amounts that can be claimed for child care expenses. A little something for everyone. The UCCB change is the big dollar amount, and that’l be hard for either opposition party to campaign against.

As an aside, I’ll be curious to see the forms you need to fill out to benefit from the income splitting – one of my colleagues joked that it will cost more than $2000 in accounting fres to claim it.

Yeah, it’s definitely going to have to be creative…and in place for the 2014 return!

I looked at the ways & means legislation (4-5 pages). It basically requires filers to do some sideline calculations (like RRSP room) to determine the hypothetical federal savings that would result from an income transfer.

I didn’t quite understand how the spousal credit worked. Didn’t have a dark room and a single light bulb to study that one.

I am not necessarily in favour of income splitting, but I think both these arguments are wrong.

Efficiency

The error in the argument is that while the market labour supply of lower-income spouses may be more elastic to taxation, the market labour of the higher-income spouse is more productive, and the non-market labour of the lower-income spouse has to be accounted for. The analysis doesn’t do this. If the higher income spouse works more in the market, and the lower income spouse works more at home, then each is probably pursuing their comparative advantage.

Equity

Equity is pretty hard to define, but it whatever it is, it can’t just be overall higher marginal taxes. Rawls’ suggestion is that equity is improved by a rule that parties behind the veil of ignorance about whether they would be the beneficiaries would pick. On that basis, the question is what rule you would pick if you didn’t know whether you would be single, in a couple with relatively similar incomes, or in a couple with relatively divergent incomes. I don’t find it easy to answer that question. Rawls assumed people in the original position are risk averse, and people can end up in one-major-earner families for reasons outside their control, so they might well want at least a compromise that gives some room for splitting.