This post is ironic.

I have a really neat new theory of what causes countries to hit the Zero Lower Bound. It's got a beautifully counter-intuitive policy implication. The government needs to tax investment, or subsidise saving, to help the country escape the ZLB. What I need is a co-author to help me do some math, so we can get a publication.

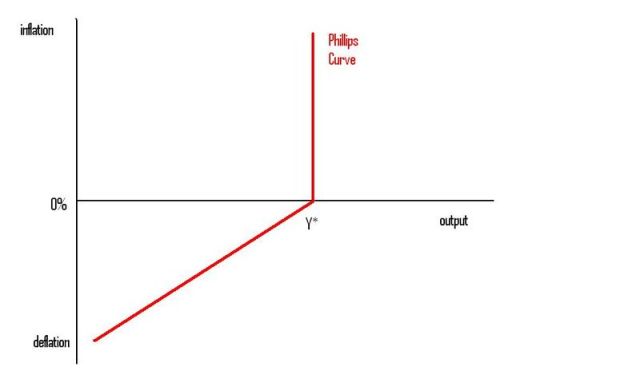

Start with a Phillips Curve that looks like this:

We know that in equilibrium the nominal interest rate set by the central bank must equal the natural rate of interest plus the inflation rate:

i = n + p

At the ZLB equilibrium we know that i=0%, and therefore the inflation rate equals minus the natural rate:

p = -n

And according to the Phillips Curve above, we will only get negative inflation if output is below potential, so unemployment is high. So there is a unique equilibrium.

Since central banks are stuck on using Taylor Rules, subject to the constraint of the ZLB, we can't expect monetary policy to help. Therefore we need to use fiscal policy instead.

What we need is a fiscal policy that could reduce the natural rate of interest down to 0%, to prevent deflation, so that the economy can return to potential output and full employment. A tax on investment, or a subsidy to saving, would reduce the natural rate of interest. Or electing a government that created a lot of uncertainty would discourage investment and encourage saving, and would reduce the natural rate of interest. And if we could push the natural rate down below 0% temporarily, to create some positive inflation, so the Taylor Rule can work again, with inflation back at the 2% target, that would be even better.

Get the intuition? It's neat, eh?

But I could never get this published in a decent journal without proving the results formally. And adding microfoundations, and uncertainty and shocks and stuff, because it's just too simple like this. And I can't do math. But I need a publication.

So I need a co-author.

[Actually, on thinking about it, my guess is that an article based on this could get published somewhere, if the math were fancy enough so the reason for the results were obscure enough. So if anyone wants to try for a Sokal hoax, go for it!]

“…if the math were fancy enough so the reason for the results were obscure enough…”

I’m sure it has been done but unlike Sokal the authors were too afraid of retribution to reveal the hoax.

Nick says “What we need is a fiscal policy that could reduce the natural rate of interest down to 0%, to prevent deflation, so that the economy can return to potential output and full employment. A tax on investment, or a subsidy to saving, would reduce the natural rate of interest. Or electing a government that created a lot of uncertainty…..”.

The “tax on investment” and the “subsidy to saving” and the “uncertainty” are all irrelevant. Nick’s objective can be achieved very simply as follows.

First, to keep things simple, assume we’re starting from scratch and that there’s no government debt. The 0% interest and full employment can be achieved simply by having the state print and spending whatever amount of money is needed to bring full employment. Interest rate is zero because the state just doesn’t issue any debt. Problem solved. That’s what Milton Friedman and Warren Mosler advocated and I agree.

Moving on to something a bit nearer the real world, one could in addition to that policy have the state borrow for specific infrastructure projects. And there it would make sense to pay the same sort of rate of interest as a private contractor would pay for creating that sort of investment. But the state as entrepreneur needs to be kept separate from the state as issuer of money and implementer of stimulus.

@Musgrave:

Sandwichman: maybe. Or maybe they just wanted the publication!

Majro: and if this was all math, with no words or diagrams, the sleight of hand would be much harder to see.

Ralph: But my “model” says that the government needs to cut infrastructure investment to get to full employment!

😉 😉 😉 😉 😉

I know. Let’s get Europe to declare war on North America. War will create a lot of destruction, for a negative natural rate. 🙂 It could be a bloodless war. Just blow stuff up. And draft people to do so. Talk about a job guarantee!

Min: An actual war which destroys a lot of capital would be a bad idea. Because it would increase the rental rate on the remaining capital, and increase desired investment, which would raise the natural rate of interest, which would require increased deflation, which would require higher unemployment. What you need is to increase the fear of a future war.

Obviously, I was also being tongue in cheek. (Although it seems like it took WWII to finally end the Great Depression.) But seriously, if enough capital is being destroyed, then the return on capital is negative. Doesn’t that mean a negative natural rate of interest? (OC, later on, with capital scarce, it is a different story. :))

Nick Rowe: “What you need is to increase the fear of a future war.”

Well, anticipation of a future war worked for Germany in the 30s, right? Although fear was not the principle emotion.

Min: “But seriously, if enough capital is being destroyed, then the return on capital is negative. Doesn’t that mean a negative natural rate of interest?”

Yes, it may do. But what matters here is the expected (immediate future) return on capital, and the expected (immediate future) natural rate of interest, and not the immediate past actual return on capital.

Thanks, Nick. 🙂

“So I need a co-author”.

I’ve heard this referred to as “calling in the wolf”: http://smallpondscience.com/2013/02/18/calling-in-the-wolf/

Jeremy: Hah! I didn’t get the Pulp fiction reference.

“I didn’t get the Pulp fiction reference.”

Warning, Pulp Fiction spoilers ahead…

One plot thread in Pulp Fiction involves two hit men, Jules and Vincent, who accidentally shoot a captive in their car in broad daylight in the middle of the city. They drive to the house of their friend Vincent and call in “The Wolf”, a highly competent fixer, to tell them how to clean up the mess before they’re caught.

The analogy here is that you’ve run into some technical problem that you don’t know how to to solve, and so you call in somebody with specialist expertise to solve it for you.

The analogy is especially amusing if you imagine that the math-savvy co-author you’re calling in looks like Harvey Keitel, and is so cool that he attends black tie parties at eight in the morning, as “The Wolf” does in the film (that’s why he’s wearing a tuxedo in the clip in the post I linked to). 🙂

Always glad to add substance and insight to the WCI comment threads. [coughs, looks around nervously] 🙂

Nick, it occurs to me that the Pulp Fiction analogy is especially appropriate here. You’re looking for someone to use a bunch of fancy math to hide the strange, rigged assumptions at the core of your model. Analogously, Jules and Vincent need the Wolf to hide the ugly mess in the back of their car. 🙂

I was thinking of neo-Fisherite worlds where everyone is a pensioner living off interest on government bonds so when the interest rate is raised, income, spending, and inflation increase and when it is lowered they all decrease, perhaps with government funding from debt and asset sales, but I haven’t thought it through.

Majromax,

Here’s a thought experiment, which involves me shifting my ground a bit. Assume government issues whatever amount of base money is needed to induce the private sector to spend at a rate that brings full employment. Plus government issues no debt.

Various private sector entities then decide to lend to other private sector entities for risk free projects and the free market rate of interest turns out to be more than zero. That will presumably have no effect on demand because amounts spent by borrowers on their projects are funded by saving by lenders, i.e. by REDUCED demand emanating from savers.

Net result is that full employment continues. So I conclude that Nick’s assumption that the rate of interest on risk free loans needs to be zero is wrong.

And if by any chance the above lending for risk free projects DOES REDUCE DEMAND, that’s easily dealt with by having the state spend more base money into the economy.

@Ralph:

Majromax,

I agree I’m assuming an “MMT framework”. Plus I agree I’m treating the interest rate as a dependent variable. Apart from that, I can’t think of anything useful to add….:-)

marjomax,

in the ideal mmt system there is no ‘involuntary unemployment’ because the government buys all unemployed labour at a fixed minimum wage. Instead of using monetary and fiscal policy to change the amount of unemployed people, it uses monetary and fiscal policy to change the amount of people employed by the government at that fixed wage. Note: the government only has to provide the funding in this scheme, not necessarily the jobs themselves.

@Philippe:

“The interesting part, where there is unemployment and we seek to not have unemployment, is rejected by the construction of MMT.”

Err, no, it isn’t.