McMaster University’s Oliver Loertscher and Pau Pujolas have a recent article in the Canadian Journal of Economics entitled “Canadian productivity growth: Stuck in the oil sands”. Here is the abstract:

We study the behaviour of Canadian Total Factor Productivity (TFP) growth over the past 60 years. We find that the observed stagnation during the last 20 years is accounted for entirely by the oil sector. Higher oil prices made capital-intensive sources of oil like the oil sands viable to extract on a commercial scale. However, the greater input required per barrel of oil slowed TFP growth. Comparing Canadian TFP growth with that of the United States and Norway reinforces these results. However, our result should not be interpreted to carry any welfare implications.

While this result is not entirely new – at least, not new to me – it is timely, and their article has brought me back to the question of why TFP estimates in the oil/gas sector display these patterns.

I think I’ve come up with a plausible conjecture. The problem is not that productivity growth in the oil sands has been exceptionally disappointing, it’s that TFP systematically under-estimates productivity growth in non-renewable extraction industries.

Here is a graph of estimates for TFP for various sectors of the Canadian economy; it’s an updated and augmented version of the chart in that old post from 2011:

(The ‘business sector’ is the private sector minus the not-for-profit sector)

I draw two conclusions from this chart:

- It’s not just the oil/gas sector. The mining sector outside oil/gas displays the same patterns as the oil sector. And as we shall see, this pattern is not unique to Canada.

- Whatever TFP is measuring in the oil/gas and the mining sectors, it is not technical progress. If we take TFP seriously, we’d conclude that output in the oil/gas sector would quadruple if it reverted to the technology used in 1973, and that mining output would double if it reverted to the technology of 2004. Nobody believes either claim, nor should they.

Let’s go back to first principles, in the form of Robert Solow’s seminal 1957 article in the Review of Economics and Statistics. Denote output by Y, the capital input by K, the labour input by L and suppose that the available technology can be represented by the the production function has the form Y = AF(K,L). The function F(K,L) captures the contribution of the physical inputs and A is an index of total factor productivity: if A increases by (say) 10%, output also increases by 10% even if the levels of the physical inputs capital and labour don’t change. A is also the only thing in this model that we can’t observe directly. Suppose also that the available technology displays constant returns to scale in capital and labour. Since we’re working at the industry level, this amounts to saying that a given production process can in principle be replicated with identical inputs to yield identical outputs.

Given this structure, it’s not hard to show that the growth rate of the productivity index A is determined by

gY – gK – αL(gL – gK) = gA

where gA, gY, gL and gK denote the growth rates of A, Y, L and K, respectively; we can measure gY, gL and gK.

The αL term is the ratio (L · AFL)/Y, where AFL is the marginal product of labour: the derivative of AF(K,L) with respect to L. We don’t observe the marginal productivity of labour either, but if we assume that labour markets are competitive and that firms are trying to maximise profits, then the marginal product of labour will be set equal to the real wage. If we choose output to be the numeraire, then αL = (w · L)/Y. This term is simply the labour share of output : total wages paid as a fraction of total revenue (since Y is the numeraire, production is the same thing as revenue).

We can now put numbers to all the terms of the left-hand side of that equation. It also has a name: the ‘Solow residual’: the part of output growth that cannot be ascribed to the accumulation of the physical inputs of production. If we fix A at an arbitrary number for an arbitrary reference year (Statistics Canada currently sets A=100 for 2017 in its data tables; I set A=100 for 1961 in the chart above), we can generate a series of estimates for the levels of A that are consistent with the estimates for the growth rate. But since these estimates for total factor productivity are recovered from growth rates and not levels, we can’t compare them across industries or countries, only across time.

We turn now to the question of how to apply this methodology to non-renewable resource extraction industries. Clearly, the available stock of the resource is an input in production in this sector: you can’t extract a resource that isn’t there. This is the sort of observation that is obvious once it’s pointed out, but seems to have been largely overlooked in this field.

Suppose now that the production function for a non-renewable resource extraction industry takes the form AF(K,L,S), where S denotes the stock of the resource remaining in the ground. Let’s again invoke the replication argument to assume that F(K,L,S) has constant returns to scale: identical amounts of capital and labour working on an identical resource stock will generate identical levels of output.

If we apply the same reasoning used to derive the relationship between the Solow residual and gA (the growth rate of the productivity index A), we get:

gY – gK – αL(gL – gK) = gA + αS(gS – gK)

where the left-hand side is the same Solow residual obtained above and can be estimated in the same way. The thing to note is that taking resources into account introduces extra terms to the right-hand side:

- αS is defined in a way analgous to αL: αS = (S · AFS)/Y, where AFS is the marginal product of the resource stock. If the marginal products of K, L and S are all positive, then αS will be between zero and one.

- gS is the growth of the resource stock. Since S is non-renewable, gS can never be positive: extraction depletes the resource stock.

The αS(gS – gK) term represents the bias of the Solow residual: if it is positive, productivity growth will be over-estimated (the left-hand side will be greater than gA) and productivity growth will be under-estimated if it is negative.

My conjecture is that the latter case generally prevails. The bias term will be negative if αS(gS – gK) < 0. We know that αS is positive, so this amounts to saying that the Solow residual will under-estimate productivity growth if gK > gS. If gS cannot be positive, a sufficient condition for a downward bias is a growing capital stock.

We can expect the bias to be weakened or even reversed during resource busts: the capital stock could decline if investment slows to the point where it is not enough to offset the effects of depreciation. If the reduction in the capital stock is strong enough to reverse that inequality (ie, gS > gK), then the Solow residual will overestimate technical progress.

In terms of estimates for TFP, we would expect:

- Weak or negative growth in TFP when the capital stock is increasing

- Stronger growth in TFP when the capital stock is declining

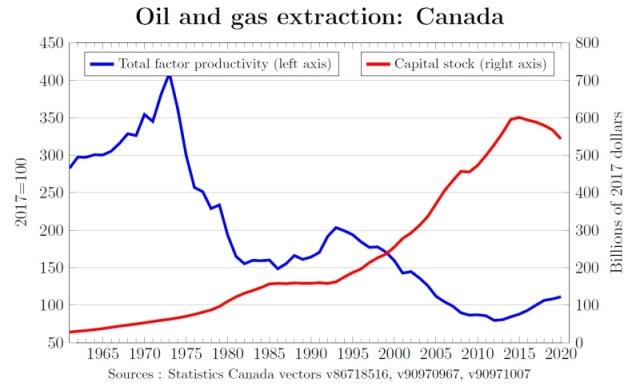

Let’s now go to the data. First up is Canada’s oil/gas sector:

I think it’s fair to claim that the data fit the pattern, at least for the last 40 years. The sharp decline in TFP between 1993 and 2013 corresponds to the strong increase in the capital stock associated with the boom years. Increases in TFP are associated with the periods of weak oil prices in the 1980s and after 2014.

Here are the data for Canada’s mining sector outside oil/gas:

The patterns here are almost exactly what this model would predict: TFP declines during the periods of rapid increases in the capital stock and recovers when growth is anemic.

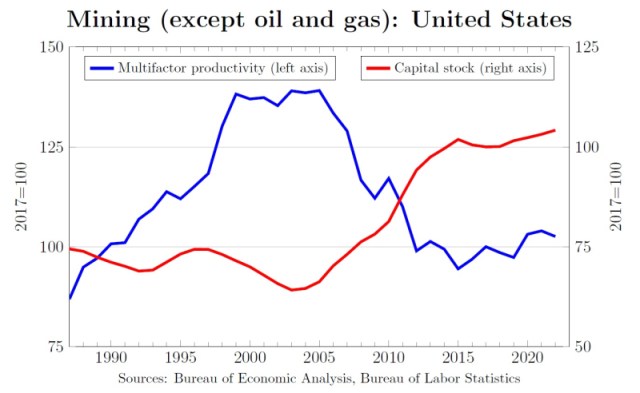

Here’s the same chart for the US mining (outside oil/gas) sector:

Again the same pattern: TFP increases when capital stock growth is weak, and declines when the capital stock expands.

On to the Australian mining sector (they don’t appear to have broken out oil/gas):

And again the same pattern: TFP falls when there’s strong growth in the capital stock and only increases when the capital stock levels off.

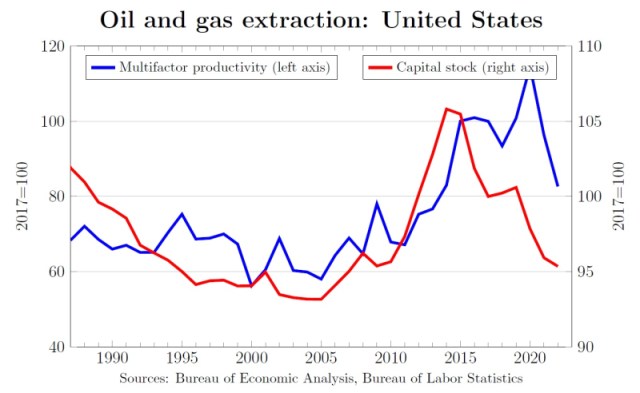

My last chart is for the US oil/gas sector, and it definitely does not fit this pattern:

I don’t know what’s going on in this sector. One guess – and I’m only spitballing here – is that the recent development of fracking techniques has has the effect of significantly increasing the recoverable resource stock, so that gS > gK. But I really don’t know.

Because of this chart, I can’t claim that every resource sector that I looked at follows the pattern predicted by the model. But four out of five is good enough for a blog post.

The only other paper I’m aware of on this theme is Pierre Lasserre’s and Pierre Ouellette’s “On measuring and comparing total factor productivities in extractive and non-extractive industries”, published in 1988 by the CJE (Jstor link). They find that incorporating the resource stock into the production function of the asbestos sector, they obtain larger estimates for TFP growth, and that the augmented model yields estimates for TFP growth that are similar to those found in the textile industry.

So that’s my conjecture: the puzzlingly weak growth of total factor productivity in non-renewable resource industries can mainly be attributed to a downward bias introduced by not including the resource stock as an input of production.

Great post, Steve, and excellent insights.

I’m wondering – if someone decides to quit their day job and make money from selling off their family’s collection of oil paintings, we wouldn’t say that they were productive. We’d figure that they were running down their assets.

And perhaps that’s the right answer here – to the extent that Canadians are living off non-renewable resources, we aren’t being very productive, and we’re in for a shock when our stocks run out.

Don’t know what’s behind this sudden resurgence in posts but keep it up guys!

A bit of work from Australia (2008), not a journal article but I think making similar points:

https://www.pc.gov.au/research/supporting/mining-productivity

I am coming at this as a former economist for the Alberta Energy Regulator who built the first aggregate capex forecasts for that organization. Part of what you are looking at is a blind spot in the analysis of TFP. Mines,

Oil sands and oil and gas projects have significant upfront capital costs. In 1996 the then Chretien Government introduced the Accelerated Capital Cost Allowance (ACCA) that allowed oil sands companies to recover the full cost of capital before the royalties start kicking in. This policy was previously extended to regular truck and shovel mines, but the oil sands operators had previously not been privy to it. Once that policy came into effect, it kicked off a massive oilsands boom. It created a perverse incentive where companies stopped caring so much about capital cost discipline, and focused purely on schedule. This is what led to robust wage growth in the trades. In 2007 the Connaervatves announced the ACCA would be phased out by 2014, and we witnessed a collapse in new oil sands investment, starting cancellations by Total of France.

What happens on megaprojects is that productivity might seem slow, as people only spend 40% or less of their time on tools. But when you need people to solve a problem, the cost of not having extra people outweighs these concerns. Any economist with notions of productivity would have a meltdown. But the truth is, when you have 10,000 people on one project, they spend a lot of time just walking to and fro, waiting on materials,

Or waiting for other work groups to finish. Also, with a sweetheart deal like the ACCA, you don’t have to worry about cost discipline.

Only in 2025, close to 20 years later, will Alberta start to see the fruits of this investment. As capital costs are paid off, higher royalty rates kick more $ into government coffers. So let that be an insight: measuring TFP of mines has to look at it in terms of the total lifecycle, not just the value or resource extraction in year C relative to investment. These projects take decades to reach maturity so TFP would be like trying to explain 18 holes of golf with 1 photograph.